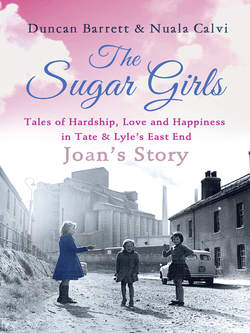

Читать книгу The Sugar Girls - Joan’s Story: Tales of Hardship, Love and Happiness in Tate & Lyle’s East End - Duncan Barrett - Страница 8

1

ОглавлениеOn Saturday 31 January 1953, with the Christmas decorations all tidied away for another year, an unusual combination of high tides and a severe windstorm coming from the North Sea conspired to blast the east coast of England with a devastating storm tide. By sunset, sea walls were giving way along the coast and the water was rushing inland, leaving a trail of destruction and ruin in its wake.

At one a.m. the watchman at North Woolwich Pier reported that the Thames had reached a dangerous level. Less than an hour later, six feet of surplus water was spilling out of the Royal Docks and onto the streets of Silvertown, where it was flushed into the local sewers and back up into the lower-lying neighbourhoods of Custom House and Tidal Basin. The public hall at Canning Town was converted into a control and rest centre, and was soon home to nearly 200 displaced local people. Refugees began to arrive from further afield, including many from Canvey Island, which had been completely submerged in water with the loss of 58 lives. The locals had fared much better, with only one fatality recorded – William Hayward, a night-watchman at William Ritchie & Son in Tidal Basin, who had escaped the flood waters only to be gassed thanks to a damaged pipe. Across Europe the total death toll was over 2,000.

By Monday morning, after much pumping from the local fire brigade, the waters had receded. But they left a carpet of thick black mud on the streets, and in the downstairs rooms of many people’s houses. The local residents mopped their ruined homes down and dragged what little furniture they owned out onto the streets, rinsing it with buckets of water and trying to avoid the rats that had been washed up from the sewers.

Although both Tate & Lyle factories escaped any serious damage, not all the girls who worked in them were as lucky. A young can-tester from Plaistow Wharf had been forced to flee upstairs when the water completely flooded the ground floor of her family’s house. The Salvation Army came round in a rubber dinghy mid-morning, passing tea and biscuits through their window. But it was many hours before the Army proper arrived with a rescue boat and they were evacuated to Canning Town Public Hall, and several days before their belongings were free of the black mud.

Not everyone, though, saw the flood in such grim terms. While most people were doing their best to stay safe and dry, one girl, Joan Cook, was rushing headlong into the water for a swim.

‘What do you think you’re doing?’ her mother cried, running after her as she waded in. But it was no use. The girl was already diving into the bracingly cold water, and emerged a few moments later, laughing and holding aloft an old boot.

‘Mum! Look what I found down here!’ she shouted.

‘Put it back, Joan,’ her mother said urgently. ‘You don’t know where it’s been!’

‘Nah, it’s all right, Mum,’ she replied. ‘The water’s washed it clean.’ She tossed the boot back into the murky depths and flipped onto her back for a few strokes.

Fortunately it was February, and no girl, however bold, could spend more than a few minutes in such cold water. Joan soon hauled herself out and staggered back towards her mother, her clothes clinging to her goose-pimpled flesh.

Mrs Cook took off her own coat and hastily threw it round her daughter, covering as much of her slippery wet body as she could manage. She hurried the dripping girl back into the house, quickly pulling the door closed behind them.

‘What were you thinking, Joan?’ she exclaimed frantically, towelling down the long blonde hair, now grown sticky and dull with the dirty water. ‘What will the neighbours say?’

‘Just felt like a dip, that’s all,’ Joan replied. ‘It ain’t every day there’s a swimming pool in the street.’

Joan lived in Otley Road, a stone’s throw from the old West Ham Stadium, where crowds of more than 50,000 gathered several times a week for the motorcycle speedway and greyhound racing. When there was a race on, half the neighbourhood seemed to pass by her front door, and she would rush outside to watch the great saloon cars chauffeuring the speedway riders past.

Joan’s father, and his mother who lived downstairs, both kept greyhounds and whippets, and raced them at the track. Nanny Cook was well known in the neighbourhood for lending money to those who found themselves a few bob short. She was also thick as thieves with the local fairground community, the Bolesworths, whose young boys she regularly took in while the adults were touring around the country. The travellers’ gratitude was evidenced in the old woman’s sideboard, proudly stuffed with silverware they had presented her with over the years.

Joan herself had never got on with Nanny Cook, who she felt favoured her younger brother John. But the appeal of the fairground connection was not lost on her. She adored the bright lights, the swirling waltzers, the colourful prizes on offer and the smell of candyfloss and popcorn, and was never happier than when the fairground folk allowed her to help out with manning one of their stalls.

Her mother, on the other hand, was not so keen. ‘I don’t know what your old mum sees in that lot,’ she would tell her husband, John. ‘And I don’t want our Joan getting mixed up with them.’

Mrs Cook, who had named her daughter Joan after herself, was a woman with aspirations for her family. Although an East Ender born and bred, she would assume the accent and demeanour of a middle-class lady when it suited her. Joan found it excruciating getting onto the trolleybus with her mother and hearing her ask the conductor for ‘two singles, if you would be so kind’.

Nevertheless, Joan adored her mother, whose warm and cheerful personality ensured she was beloved by everyone she met. And Mrs Cook’s desire for respectability had not come from nowhere. Her own mother, Nanny Polly, was a former ship’s scrubber who had worked hard all her life, and had often been forced to pawn family jewellery in order to make ends meet. She valued such small luxuries as she could afford, like a sparkling white tablecloth and a set of china teacups, which would be whipped out at the drop of a hat for visitors. But despite this positive example, not all her progeny had taken such a refined approach to life as Mrs Cook had, and some of their in-laws were rather less salubrious than the two of them would have liked.

Mrs Cook’s brother George had married a woman who already had two children from a previous marriage. To make matters worse, she was the madam in a brothel, where her daughter was employed as a maid. Their son had spent time in prison after using his own vehicle as the getaway car in a robbery, and was later found dead on a bridge near Portsmouth, on his way back from a trip to buy bootleg cigarettes.

Meanwhile, Mrs Cook’s brother Peter had a new young wife called Iris, who had produced her first baby alarmingly soon after their wedding. ‘Probably hooked him,’ Joan heard her mother mutter one time when they were round visiting the couple, who unfortunately lived upstairs from Nanny Polly and were therefore rather hard to avoid.

As ever, Mrs Cook’s anxieties about Iris had served to have the opposite effect on her daughter. Joan was in awe of the attractive young woman, who was only ten years her senior. Iris wore a red chiffon headscarf and worked at the local cinema, and to Joan she exuded pure glamour. Best of all was Iris’s bedroom, where the mantelpiece was piled high with all the latest make-up. Every weekend, when Joan and her mum went to visit Nanny Polly, she would dash straight upstairs to see if Iris was in, and her mum would have a job dragging her back downstairs to see the rest of the family.

‘I’m sure your aunt is very busy,’ Mrs Cook would call up hopefully. ‘Why don’t you come and say hello to Nanny?’

‘It’s all right, love,’ Iris would shout back from her room. ‘I’m just showing Joan how to do her mascara.’

Equally trying for Mrs Cook was Joan’s choice of best friend at school, Peggy, who came from a local Irish family. On the face of it, the two households had a lot in common: Peggy’s dad worked in the docks, just as Joan’s did, and her mum was a ship’s scrubber, just as Joan’s grandmother had been. But Peggy’s family were poorer, and their tastes were rather different.

‘Can I have a fried-egg sandwich?’ Joan had asked her mum one day when she came back from a visit to Peggy’s.

‘A fried-egg sandwich?’ her mother asked her, incredulously. ‘What on earth do you mean by that?’

‘Well, you fry an egg, put it on some bread, add a bit of brown sauce, put another piece of bread on top and then chop it in half,’ Joan replied, innocently.

‘And where did you hear about this?’ Mrs Cook enquired.

‘Down Peggy’s,’ came the expected response.

No more was said on the matter, but from then on Joan made sure to get her egg sandwiches at her friend’s house rather than asking her mum to provide them.

Fortunately for Joan’s mother, in joining the Cook clan she had married into money, which made keeping her own house as nice and proper as she liked that bit easier. Whether it came from cash-rich Nanny Cook or from his own hard work, her husband was somehow able to make sure that the family never wanted for anything. They were the most well-off people in their neighbourhood by a long shot, and the tally man didn’t even bother knocking on their door since they could afford whatever they wanted without hire purchase. Mrs Cook had fur collars on her coats and they always had the latest modcons, paid for up-front in cash. Mr Cook was the proud owner of a motorbike, and his children bundled into the little sidecar for regular days out. Later, he even splashed out on an old black Ford 10. When domestic fridges came on the market, the Cooks were the first in the area to buy one, and Joan did good business selling ice cubes to kids in the street.

Most extravagant of all was the family’s holiday home, a caravan near Burnham-on-Crouch, complete with a fully fitted miniature kitchen and net curtains on all the windows. Joan lost count of the number of weekends and summer holidays she spent cooped up there with her parents and little brother, with no one her own age to have fun with. To her mother’s dismay, she dreamed of joining the other boys and girls from Otley Road, who went hop-picking for six weeks of the year and returned with romantic-sounding stories of sing-songs around open fires and gazing up at the stars.

After much badgering, Mrs Cook decided that the best way to knock this notion on the head was to go along with it, and agreed to let her daughter head off with the neighbours instead of accompanying the rest of the family to the caravan.

Once there, Joan realised she had made a terrible mistake. Spending all day stripping the bines was exhausting, and she hated the bitter taste of the hops, not to mention the mud and dirt – and sleeping every night in a tin hut. When her mother came to visit her, she cried and begged to come home.

‘All right, love,’ Mrs Cook laughed, affectionately. ‘Perhaps now you’ll realise how lucky you are.’

The Cooks fancied themselves a cut above the rest in other ways, too. Joan’s parents didn’t drink – unlike their neighbours, the aptly named Dances, who would stagger down the road every weekend singing on their way back from the pub. They had never smoked, not even when Mrs Cook was working at a cigarette factory. They wouldn’t dream of swearing, either out in public or within their own walls.

In June 1953, when the coronation of the new Queen Elizabeth turned the East End into one big street party, the Cooks declined to RSVP. Otley Road had been chosen as one of 70 ‘roads of revelry’ hosting festivities in West Ham, and the 60 local kids were joined by a contingent from a nearby children’s home for a fancy-dress parade, while neighbours vied with each other to put up the most bunting and flags. Mr and Mrs Cook, however, did not decorate their house, nor did they take their places at the long row of tables lining the centre of the road, where the inhabitants of every other house were eagerly eating, drinking, laughing and singing. Instead, they watched discreetly from their doorway.

Although they projected a picture of respectability, the Cook family hid an ugly secret, one that sadly was all too common at the time. The outwardly affable Mr Cook had a temper that often bubbled over into violence, and while the kids were fortunate enough to be spared his blows poor Mrs Cook bore them frequently.

Each evening, mother and children would quake with fear when Dad came home from work, waiting to find out what mood he was in. Joan and her brother John would do their best to protect their mum, jumping on top of her and trying to shield every inch of her body from his blows. But sometimes Mr Cook was too quick for them. Watching the beatings night after night, Joan grew determined that no one would ever make a victim out of her.

The source of Mr Cook’s anger was hard to fathom, but his own life had not been an easy one. Perhaps feeling displaced in his mother’s affections by the fairground children had left him with a burning resentment. Perhaps the trauma of more recent experiences had poisoned his personality. A crane driver in the docks, he had accidentally killed a man by dropping a load of coal on top of him. On a single day he had been forced to attend two inquests at the same coroner’s court – one for the victim and another for his own father, who had died in his sleep just a few days before.

Whatever the reason, Mr Cook also struggled to express affection for his children, and Joan could not remember a time in all her life when he had so much as put his arm around her. He was, however, very attached to his whippets, which he had blessed with human names: Peter and Poppy.

By the time Joan left school at the age of 15 – the leaving age having now been raised by a year – her mother had already made up her mind what to do with her. Although no one would have known it, Mrs Cook had spent her own early life working at various factories, including Tate & Lyle’s Thames Refinery, and she was determined that her children would not follow in her footsteps. ‘My daughter is no factory fodder,’ she would say. ‘I’m getting her a job in an office.’

This was easier said than done, since Joan’s academic record was less than stellar. She had been placed solidly at the bottom of almost every class at school, where the only talent anyone had discerned in her was a remarkable capacity for rhyming. From a young age, Joan had talked to her friends in rhyme, firing back rapid, perfectly sensible responses to whatever they said, and turning every exchange into a couplet.

The nuns who taught her at school found it rather exasperating. ‘Write the answer on the board,’ they would tell her, only to hear in reply, ‘Yes, Miss, let us praise the Lord’ – which they couldn’t really argue with. It was an unusual ability, to be sure, but it didn’t really lend itself to gainful employment.

Joan did have one skill useful for office work – like her mother, she was an excellent mimic. When Mrs Cook secured her an interview for an office job at CWS Flour Mills in Silvertown, she reminded Joan to follow her example. ‘Talk proper,’ she told her. ‘None of your ain’ts and fings!’

Putting on her plummiest accent, Joan sailed through the interview and soon found herself operating their switchboard. ‘Good afternoon, may I transfer you?’ she would ask demurely, before pushing the little wooden sliders up and down to connect the calls to the relevant offices. It was fun to begin with, but after many months in the job, with only a few old fogies for company, Joan was desperate for something more exciting.

Her friend Peggy, whose parents could ill afford Joan’s mother’s prejudices about factory labour, had taken a job among the sugar-packing machines on the Hesser Floor at Tate & Lyle, and the more Joan heard from her friend about the life there, the more she felt convinced it was for her. ‘So you go out every weekend,’ she quizzed her, ‘and the company has its own parties?’

‘Yeah,’ Peggy replied proudly. ‘And the pay’s brilliant, what with the bonuses and all.’

In the end, Joan chucked in the job at the flour mill without asking her parents’ permission. ‘Oh, Joan, what have you done?’ her mother wailed when she heard the news. But it was too late. Her daughter had already gone to the Personnel Office at Plaistow Wharf and got herself a position on the Hesser Floor, where an early and late shift were now running in addition to day-work.

Joan couldn’t have been happier – she had found a lively, vibrant place to work, where she was surrounded by people her own age. Every day she left home with a spring in her step, eager to spend time with the other sugar girls. Her colleagues even seemed to appreciate her little rhyming poems, which she scribbled away in a notebook during her breaks. Once they realised what she was up to, they began to put in requests.

‘Can you write one about me, Joan?’ Peggy asked one morning, while a group of girls were gathered round smoking in the toilets.

‘All right then,’ Joan replied, happy for the challenge. She thought for a moment.

‘Peggy O’s a charming lass, her smile so full of grace / But if you pinch her on the ass, she’ll smack you round the face.’

‘You cheeky cow!’ Peggy squealed, between fits of giggles.

Another girl on the floor was desperate for a ditty about the labour manageress, Miss Smith - or The Dragon, as she was known - who had just given her a particularly humiliating telling-off. Joan was happy to oblige.