Читать книгу GI BRIDES – June’s Story: Exclusive Bonus Ebook - Duncan Barrett - Страница 5

1

Оглавление‘Last orders, please!’ Mr Baker called, ringing the bell at the bar.

His daughter June sighed as she finished pulling a pint of Ansells for one of the Irish labourers who were in Birmingham working for the war effort. Not long now, she thought, glancing up at the clock on the wall, which read five to ten. The hordes of drinkers were already well past merry, and she was exhausted from being on her feet all evening after a long day at work.

At the other end of the bar, she could see her dad’s short, stubby arms gesticulating as he recounted one of his favourite stories, prompting a group of regulars to burst into raucous laughter. Mr Baker had only been running the Lister Tavern for a couple of years, after leaving his job making parts for tanks at the Austin car factory, but it was clear that he had found his vocation, and he loved holding court with the punters. At the pub, he was also perfectly placed to conduct his various black-market deals – down in the cellar, secret stashes of anything from petrol to ladies’ coats could often be found amid the beer barrels.

Mrs Baker tottered over in her high heels. With her flaming red hair and ostentatious hat – one of many she owned – she had an air of faded glamour about her. ‘Pour me another brandy and soda, love,’ she said, holding out her glass. June did as she was told, then watched her mother totter off again. Mrs Baker had a tendency to overindulge – not helped by the fact that the punters often bought her drinks. She always described herself as the last of the party girls, and June had often heard stories about her days as a flapper in the Twenties.

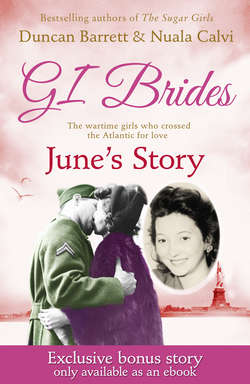

Both June’s parents were outgoing, gregarious types – as was her younger sister Pam – and June often wondered how they had ended up with such a shy daughter as herself. She was a delicate girl, just five foot three, with a porcelain complexion and a rounded, doll-like face, and she barely looked her sixteen years. She didn’t feel she had the thick skin required for pub life.

One of the Irishmen came up to buy another round of beers, and June began pulling the pints, doing her best to resist his attempts to draw her into conversation. She took the man’s money and went to get the change out of the till, but when she put it in his hand, he eyed it suspiciously.

‘You’ve given me the wrong change here,’ he complained.

‘I don’t think so,’ June replied quietly.

‘Are you calling me a liar, now?’ he demanded.

‘No, I –’

‘Well, count it again then!’ he shouted, throwing the coins back at her.

Her eyes pricking with tears, June scrambled around on the floor trying to pick up the money, but by the time she stood up again the man had already wandered off with his drinks.

To her relief her father bellowed, ‘Time at the bar, gentlemen!’ and June gratefully fled upstairs to her bedroom. She wished she never had to work in the pub again.

June’s parents had met through their mutual love of dance, and they had cut quite a figure together. With his dramatic nature, Mr Baker favoured the tango, while Mrs Baker preferred the charleston. She was crazy about her husband, but he had always had a wandering eye and often complained to June, ‘If it hadn’t been for you coming along, I never would have married your mother.’ Mrs Baker, meanwhile, wasn’t exactly maternal, and June often wondered if she had wanted children herself.

June couldn’t have been more different from her parents. From her earliest years, she had known exactly what she wanted in life – to be a housewife and mother. She longed for a home of her own, and as a child she had set up a hidey house in the shed where her father kept his tools, putting up some lace curtains donated by her grandmother and taking her dinner out there every night to eat alone at a little makeshift table and chairs. She adored babies, and her most precious possession was a china doll given to her by Grandma Baker, complete with real baby’s christening clothes. As she grew older, June would beg the neighbourhood mums to let her take their children out in their prams, and walked with them for hours, pretending they were hers.

Perhaps her love of babies stemmed from having lost a little brother, Derek, to pneumonia when she was just four years old. Her earliest memory was watching from a neighbour’s window as her parents disappeared into a big black car, and being told that they were going to her brother’s funeral. Derek’s death had come during the Great Depression, at a time when the Bakers were struggling to make ends meet. When the girls’ shoes wore out, their father had made soles for them out of cardboard, since there had been no money for new ones. He had taken all manner of odd jobs, including a stint as the doorman at the Odeon, and would sometimes sneak his daughters into the matinees. June grew up loving the glamorous world of the Hollywood movies, which provided an escape from the grim reality of life in 1930s Birmingham.

June had been twelve when war broke out, and suddenly school days were punctuated by drill practice, and meals reduced to dreary rounds of beans on toast and spam, thanks to rationing. She and her sister Pam were evacuated to Wales, where they stayed with a family who only spoke Welsh – as did their new schoolmates, who excluded them completely. ‘Dad, please come and get me – I don’t like it here!’ June had begged in her letters home, and eventually Mr Baker had reclaimed his daughters, driving them all the way back to Birmingham in his little Austin 7, powered by black-market petrol.

The following year, the Birmingham Blitz began. More than 2,000 local people lost their lives and many more were made homeless. Only London and Liverpool suffered more casualties at the hands of the Luftwaffe.

Mr and Mrs Baker refused to have an Anderson shelter in their back garden, however, and preferred to take their chances in their beds. Their one concession to safety was putting the children to sleep under the stairs when the air-raid siren sounded. Most nights Mr Baker was out anyway, since he was an air-raid warden, and sometimes he took June on his rounds with him. It was frightening witnessing the terrible fires burning all over the city, but June preferred to be outside, hearing her father blow confidently on his whistle, rather than cowed under the stairs with her sister.

June’s grandparents had a lucky escape when a bomb landed right outside their house. It came in at an angle and went under the building, doing some minor damage, but did not explode – and when the bomb squad came to disarm it, they soon discovered why. Inside the shell case was a note that read, ‘From your friends in Czechoslovakia’. The prison-camp workers who had constructed the bomb had kindly left out the fuse.

June knew that many people were less lucky than her own family. One night, Mr Baker had bundled his wife and children into the car and driven them up into the hills. June had sat and stared, transfixed by the immense fires raging in the distance. It looked as if her whole city was being burned to the ground.

June left school at fourteen and, keen to get away from pub life, volunteered for the Land Army. She had seen the posters showing girls cradling baby lambs under the words ‘Back to the land. We must all lend a hand’. Having never been outside the city except for her brief period as an evacuee, she pictured an idyllic scene of rustic bliss.

June and her fellow new recruits were taken by bus to a farm some way outside Birmingham, where to her horror they were issued with manly corduroy trousers and clumping great boots. The next day they were up at dawn, and set to work digging potatoes. It was back-breaking, and while the other girls were hardy types who seemed unfazed by the physical labour, the diminutive June struggled to keep up, her shovel barely breaking the stone-hard earth.

It was almost dark by the time the girls returned to the farmhouse, and they had built up an enormous appetite from their exertions, but the meal provided by the farmer’s wife was far from hearty.

After dinner, June was looking forward to a nice hot bath to relieve her sore muscles and wash away the mud that was now caked onto her skin and hair, but she discovered that there were to be no such luxuries. Each girl was allowed a small bowl of cold water to perform her ablutions, before lights-out at 9 p.m.

As she lay shivering under a thin blanket, June realised she had made a terrible mistake. Being a Land Girl was far from the fluffy experience the posters had suggested, and there could be few girls less cut out for hard labour than she was. Within days she was back home.

June’s father quickly saw to it that she was contributing to the family finances, however. Her headteacher’s reference had declared her ‘pleasing in her manner and appearance’ and ‘fastidious about details’, and it was enough to win her a job as a trainee telegraphist at Birmingham Post Office. There, she cut and pasted the ticker-tape messages, many of them expressing condolences to the families of men killed in action. After work, it was back to the dreaded pub, where she would sometimes be called on to help out behind the bar.

There was little to relieve the tedium of her weekly routine. June had no love life to speak of, since most of the eligible young men she knew had by now been called up. The cinema remained her only escape, and the Odeon was increasingly becoming her second home. She revelled in the glamour of the silver screen, and found herself longing to live in America – a land where young women drove sports cars and lived in huge houses with swimming pools. She idolised Hollywood stars like Ingrid Bergman, Betty Grable, Lana Turner and Hedy Lamarr, and lusted after the fashionable clothes they wore, so different from the drab fare on offer in English shops. Having seen a pair of peep-toe heels on one Hollywood starlet, June had rushed home and immediately cut the toes out of a pair of her own shoes, but it didn’t quite have the same effect, and to her annoyance her mother made her throw them away.

To June, America was a mythical land that seemed a million miles away, and growing up she had never thought she would actually meet an American. But when the United States joined the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, GIs began arriving in Britain in preparation for the invasion of Europe. One day, June was cutting through the graveyard of Birmingham Cathedral to catch her bus home when she noticed a soldier walking towards her. His light mushroom-brown uniform – which was of a superior cut and quality to that of a British Tommy – instantly marked him out as an American. He was tall and tanned, with cropped blond hair so fair that it almost looked white. In the drab setting of the churchyard he seemed utterly out of place, as if a movie star had just dropped out of the sky.

Oh my God, he’s coming to talk to me, June thought, doing her best to contain her excitement as the man sauntered over.

‘Say, do you know any place round here where I can get a bite to eat?’ he asked.

June was dazzled by his eyes, which were a sharp, piercing blue. It took her a few moments to process his accent, which had more of a drawl to it than the Americans she was used to on the silver screen.

‘Um… My parents have a pub not far from here,’ she said eventually. ‘My mum could make you something to eat.’

‘Sounds good to me,’ he replied, and accompanied her to the bus stop.

It was only two stops to the Lister Tavern, and all the way the GI kept up a steady stream of conversation. He told her his name was Omar Borgmeyer – ‘Borgy’ to his friends – and that he was from Saint Charles, Missouri. June nodded, although she had never heard of Missouri, and wondered if it was anywhere near Hollywood. All she could think was: I’m talking to a real, live American!

As June and Borgy came into the pub, Mrs Baker sprung up from her bar stool in surprise. ‘Who’s your new friend?’ she asked, her eyes going over Borgy’s smart uniform and the sergeant’s insignia on his jacket.

‘This is Borgy,’ June replied, feeling herself go red. ‘He wants something to eat.’

‘If it’s not troubling you too much, ma’am,’ the GI added.

‘No trouble at all,’ replied Mrs Baker with a little laugh, clearly enjoying being called ‘ma’am’. ‘How about a nice cheese and pickle sandwich?’

June felt mortified – surely Americans were far too glamorous to eat cheese and pickle sandwiches?

‘That oughta just about hit the spot, ma’am!’ Borgy replied, to her astonishment.

They went over to one of the battered old pub tables, and Borgy pulled out a chair for June. He certainly has good manners, she thought.

A few moments later, her mother arrived with the sandwich, which she had garnished with a pickled onion speared on a toothpick. June watched as Borgy wolfed the food down hungrily, declaring it to be the best meal he had ever had.

Then he pulled out a packet of Lucky Strikes and lit up. ‘Want one?’ he asked.

June nodded, and he handed her his cigarette, then lit another for himself.

June had smoked before, but as soon as she took a drag on the Lucky Strike she realised it was much stronger than the English cigarettes she was used to, and she couldn’t help coughing. Borgy smiled. ‘Too much for you, huh?’

‘It’s fine,’ June said, smiling. She didn’t want him to think she was unsophisticated.

June was shy enough at the best of times, but in the presence of the American she found herself more tongue-tied than ever. Fortunately, Borgy did enough talking for both of them, telling her all about his job as clerk to an army general, and how he had joined up straight out of high school.

‘I wanted to go to college, but I’m the oldest of eleven so I had responsibilities,’ he said.

June couldn’t quite believe she had heard him correctly. ‘Eleven?’ she repeated.

‘Why, sure,’ Borgy replied. ‘There’s me, Ruth, Vincent, Alfred, Mary, Millie, Genevieve, Dottie, Louise, Butch and Rita.’

Mrs Baker was listening in from the bar. ‘Your poor mother gave birth to all those children?’ she asked incredulously.

‘Yes, ma’am, she sure did,’ he replied. ‘And being the eldest, I had to learn to wash, cook and sew for all of them!’

‘Oh June, you’ve got a real catch there!’ said her mother, and again June felt herself turn red.

June discovered that the Borgmeyers were of German ancestry, which accounted for Borgy’s blond hair. But he didn’t seem to have any qualms about fighting the Germans, and was quite the all-American boy.

June felt she could have sat listening to Borgy all night, but to her disappointment he had to go. ‘They’re bussing us back to base,’ he told her. ‘But I’ll see you again soon.’

He flashed her a smile, causing her to feel lightheaded and giddy, and then he was gone.

June couldn’t believe her luck. Hollywood, it seemed, had come to Birmingham.