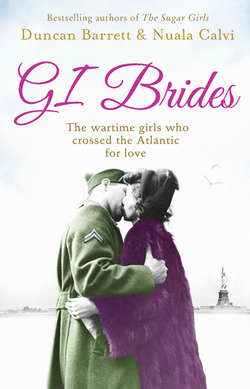

Читать книгу GI Brides: The wartime girls who crossed the Atlantic for love - Duncan Barrett - Страница 11

7 Margaret

Оглавление‘Margaret Joy Boyle, will you take Captain Lawrence McCaskill Rambo to be your husband? Will you love him, comfort him, honour and protect him, and, forsaking all others, be faithful to him as long as you both shall live?’

‘I will.’

As she said the words, Margaret just hoped that the skirt suit she was wearing was doing a convincing job of hiding her pregnancy. She was now five months along, but thankfully it wasn’t showing too much.

Her attempt at aborting the baby had failed, and she had been left with no option but to tell Lawrence everything. To his credit, he had proved a Southern gentleman in deed as well as manner, and had immediately said he loved her and wanted to marry her. She knew she was lucky – many GIs who got their girlfriends pregnant simply put in for a transfer and were never heard of again, and the army hierarchy was adept at blocking women from tracking down errant fathers.

Margaret and Lawrence had waited until after her twenty-first birthday in October 1943, so that no explanation had to be given to her parents. Not that either of them had come to the wedding. Margaret had written to her mother in Ireland but received no reply, and her father was once again overseas with the Army. Her grandmother had come up to London from Canterbury for the service. Sitting in the front pew of St Mary Abbots in Kensington she looked on disapprovingly. She couldn’t understand why her granddaughter had decided to marry an American of all people.

With so few guests at the ceremony there was no reception to speak of, and Margaret and Lawrence went back to the flat he had rented for them in Pembridge Villas, Notting Hill.

Margaret knew she wasn’t in love with her new husband, but by force of will she had put her old boyfriend, Taylor Drysdale, out of her head and was trying her best to focus on Lawrence instead. There were certainly things to recommend him. They had a love of books in common, and he was intelligent and charismatic. He was a decent man, and hadn’t deserted her.

Moreover, he had told her that his family in Georgia owned a lot of land, so she gathered that the Rambos were wealthy. His descriptions of growing up in a beautiful white Greek Revival mansion sounded like something from Gone with the Wind, and Margaret began to look forward to one day going to Georgia.

Once she was married, Margaret left her job at the ETOUSA headquarters and spent most of her time sitting at home reading novels. One day in December, when she was only seven and a half months pregnant, she felt a warm liquid trickle down her leg. She looked down and to her horror realised that her waters were breaking.

She heaved herself up, walked as quickly as she could to the phone in the hall and called an ambulance. As she was rushed to Hammersmith Hospital, she was struck by the bitter irony of her situation. Trying to get rid of the pregnancy, alone in her room, had been the darkest hour of her life. Yet now, just when she was beginning to be hopeful about her future with Lawrence, she stood to lose the child.

By the time she arrived, there was nothing the doctors could do to stop the baby from coming, even though it was still in a breech position. The labour took twenty agonising hours and Margaret did her best to breathe through the waves of pain, hoping and praying that the child would survive despite being six weeks premature.

Just as the baby was finally coming, the doctor shouted, ‘Quick! She’s breathing in.’

The breathing reflex had kicked in while the child’s head was still in the birth canal, and she was inhaling mucus. If it went on too long she would be brain-damaged.

The doctors managed to extricate her and the cord was hastily cut before she was rushed out of the room.

‘What’s happening?’ asked Margaret, so weak after almost a day in labour that she could hardly speak.

‘Don’t worry, Mrs Rambo. They just need to clear her tubes,’ the midwife said, patting her hand.

News soon came that baby Rosamund was now breathing normally, but the doctors couldn’t say what effect those first few minutes without oxygen might have had.

‘I want to hold her,’ Margaret sobbed. But Rosamund was so tiny, at just three pounds three ounces, that she had to be kept in an incubator, and Margaret was not able to see her until the next day. Even then, she wasn’t allowed to pick her up.

Margaret was sent home, but she had to leave Rosamund behind, and since the baby was too small to breast-feed she had to express milk for her and take it to the hospital every day.

Eventually, Margaret was allowed to take the baby home, but she felt that the separation of the first few weeks had made it hard for her to bond with Rosamund, and even harder for Lawrence to do so.

He seemed distracted and fretful, and explained that he was under immense pressure at work. He was helping to plan the equipment needed for D-Day, and was coming home later and later from the office. Margaret worried about the long hours he was putting in, and knew that having a screaming baby in the house wasn’t helping. Sometimes he didn’t come back until eleven or twelve at night, having gone for a drink after work, which he said was the only way he could unwind at the end of the day. He would often wake in the night and lie there tossing and turning until morning.

He also seemed to be anxious about money. When bills arrived they sent him into a fit of anxiety, and he scratched out endless sums on pieces of paper, then screwed them up and threw them into the bin. ‘Don’t you worry your pretty head about it, my dear,’ he told Margaret, when she asked him if something was wrong.

One day Lawrence arrived home late again, clearly already more than tipsy. He was carrying a bottle of whisky and went straight to the kitchen and poured himself a large glassful. Margaret watched in surprise as he knocked it back, then immediately poured himself another one and knocked that back too, as if it was no stronger than water.

‘Lawrence, are you sure that’s a good idea?’ she asked, concerned.

He turned to her, his familiar features contorted into a furious scowl and his dark-brown eyes flashing with anger. ‘Don’t you go telling me what to do!’ he shouted.

The baby started to cry and Margaret rushed from the room to comfort her. As she soothed the child she could feel her heart racing with fear. The man who had just spoken to her seemed like a completely different person to the husband she knew.

When the baby calmed down, Margaret crept into bed, hoping that by now Lawrence had drunk enough to fall asleep in his chair.

The next morning when he went off to work he looked a little worse for wear, but acted as if nothing had happened. He kissed her goodbye as usual and went on his way. The previous night’s behaviour must have been an aberration, she told herself, and she tried to put it out of her mind.

The following night Margaret was already asleep when Lawrence came in, and they didn’t have a chance to talk. But on Friday, he once again returned home tipsy and produced a bottle of whisky from his pocket. He seemed to barely notice her as he set about pouring himself a large drink.

Margaret felt instantly nervous. ‘Have you had any supper?’ she asked, and when he didn’t reply she quickly went to make him some food, hoping it might sober him up.

But in the meantime he had drunk half the bottle. The wild, furious look was back in his eyes, and once again he seemed transformed into a completely different person. The Southern gentleman was gone and in his place was someone she didn’t recognise.

‘I don’t want that!’ he slurred, as she put the food in front of him. He shoved the plate away, sending it crashing onto the floor.

Margaret didn’t stay to see what he would do next. She ran into the bedroom, and this time she locked the door. From under the covers, she could hear crashing and banging noises, and dreaded to think what he was doing.

In the morning, Margaret was woken by a gentle knocking on the door. When she opened it, there her husband stood, his brown eyes full of grief. ‘I’m so sorry, Margaret,’ he said. ‘I don’t know what came over me last night. I’m under so much pressure at work, I just can’t think straight.’

He looked overcome with shame and regret, and she couldn’t help feeling sorry for him. ‘It’s all right,’ she said, shakily. ‘But Lawrence, please don’t bring whisky back to the house again.’

‘No, of course not,’ he agreed. ‘Margaret, you are the finest wife a man could have.’ He kissed her goodbye, gave her an adoring look, and then he was gone.

When she went into the kitchen, she saw that he had cleared up the broken plate and food, but in the living room she found that the electric heater had been smashed to pieces. So that was what the crashing and banging had been. She shuddered to think of him in such a violent rage.

Margaret couldn’t help feeling angry towards the Army, who were clearly putting her husband under such terrible stress that he was buckling. She was worried he might have some kind of collapse.

The next few nights Lawrence came home earlier and did not bring any whisky with him. Margaret was relieved, but she was still worried about him, since he seemed anxious and again wasn’t sleeping well.

One day Lawrence came home and announced, ‘I’ve found somewhere much better for us to live. We’re moving immediately.’

‘But don’t we have to give notice on our flat?’ she asked him.

‘I’ve arranged all that,’ he told her. ‘Just pack our things and we can go there now.’

Margaret was surprised, but she hoped that a change of scene might help her husband. She did as he said and followed him to an address in Rabbit Row, half a mile away.

When they arrived, she found it was a small mews street that had been badly bombed earlier in the war. But she didn’t want to complain, so she got on with the unpacking.

The new flat didn’t seem to do anything to lighten the considerable load Lawrence was carrying, however. One day, while putting away some laundry, Margaret discovered two empty whisky bottles in his sock drawer.

Worse, a letter arrived addressed to her from their previous landlady, Mrs Campion, demanding payment for the electricity, phone and cleaning bills, as well as the cost of the smashed electrical fire. The woman said she had spoken to Captain Rambo several times about the bills, and he had promised to pay them, but she had received nothing. So that’s why we had to leave in such a hurry, thought Margaret.

She decided she would speak to Lawrence that night, and planned out in her head what she was going to say: that he needed to tell his superiors his workload was too large, that he needed a break and that she would help him keep on top of the bills. She just hoped that Lawrence would come home sober and at a reasonable hour.

That afternoon, there was a knock at the door and Margaret went to answer it. She found an American military policeman waiting outside. ‘Mrs Rambo?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

‘Ma’am, I need you to pack a bag and come with me. Your husband has been arrested.’

‘What for?’ Margaret asked, horrified.

‘I understand he’s been running up bad debts, ma’am. He’s being held in a US Army hospital in Lichfield.’

‘Why, what’s wrong with him?’

‘Suspected alcohol poisoning, ma’am. They’re drying him out before he can be court-martialled. I’m here to take you and the child up to Lichfield.’

Margaret couldn’t believe what she was hearing. In a daze she went back into the flat to pack her bag, and then she and Rosamund left with the military policeman.

In the car up to Staffordshire, she felt too humiliated to ask any more questions. What on earth would her father, a respected major in the British Army, think if he knew his daughter’s husband was being court-martialled? She had married Lawrence to save her family from shame, but now he was bringing it upon them anyway.

While Lawrence was being treated, Margaret passed the time in Lichfield at the nearby Red Cross centre, where, to keep her mind off things, she volunteered to type letters for US servicemen, while Rosamund stayed in a day nursery. After a while, she was allowed to visit her husband, and was relieved to find him sitting up in bed looking rested and returned to his old self. ‘Lawrence, I’ve been so worried about you,’ she told him.

‘I’m sorry to worry you, my dear,’ he said, stroking her hair lovingly. ‘I got myself into a terrible mess, with all the stress of the war and the hospital bills we had for Rosamund. When I explain everything to the court they’ll understand.’

‘Can we go home now?’ she asked.

‘I’m being sent to another hospital for some tests,’ he said. ‘Routine procedure before a trial.’

Margaret nodded. On her way out she stopped the doctor and asked where Lawrence was going. ‘He’s being transferred to the 96th General Hospital near Worcester for observation,’ he told her. ‘They have specialist psychiatric facilities there.’

‘But why?’ asked Margaret. ‘There’s nothing wrong with him, is there?’

‘We have to determine whether he’s responsible for his actions,’ the man told her. ‘That requires a neuro-psychiatric examination.’

Before long, Lawrence was passed fit to stand trial, and once he was released from the hospital, he was taken to London for the court martial. Margaret had been called as a witness, and she travelled down separately. Her mind was in turmoil – as well as worrying about Lawrence’s impending trial, she had just learned from a doctor that she was pregnant again.

On the day of the court martial, Margaret felt sick with shame as she watched the first witness take the stand – a Miss G. M. Blayney from the American Red Cross club on Charles Street, Mayfair. ‘That’s Captain Rambo, over there,’ she said, pointing to Lawrence, who looked down at the floor. ‘I recall cashing a cheque for him on 24 January.’

The young woman was presented with the cheque. ‘Yes, that’s it,’ she said. ‘I took it from him and gave him ten pounds cash for it.’

The cheque had been returned from the bank marked ‘insufficient funds’.

‘Thank you, Miss Blayney,’ the judge said.

Next, a Mrs Gwendolen Sommerville was called from the Red Cross’s Jules Club. ‘I cashed a check for Captain Rambo on 15 January for ten pounds,’ she said. ‘There’s an entry in our club’s cheque registry.’

Again, there had been no money in Lawrence’s bank account.

One after another, women from the Red Cross clubs stood up to testify that Lawrence had obtained cash from them with cheques that were returned marked ‘insufficient funds’ or ‘no account’. Twelve times he had pulled the same trick – at the Duchess Club, the Reindeer Club, the Nurses Club, the Washington Club, Rainbow Corner – all the most famous GI hangouts in central London. In total, he had swindled them out of £103.

Margaret was appalled. Of all the institutions to steal from, to target the Red Cross seemed beyond the pale.

Lawrence’s bank manager, Mr Wigmore, from Barclays Bank on Oxford Street, told how Lawrence had been overdrawn for a year, by sums of as much as £96. ‘I was constantly in touch with Captain Rambo by means of personal interviews, telephone calls and letters, and was continually pressing him to repay the money he owed the bank,’ he told the court.

No wonder Lawrence had seemed distracted and fretful all the time, thought Margaret.

To her surprise, her own bank manager from Lloyds was also called to testify. He identified seven of the cheques written to the Red Cross and told the court: ‘These cheques were taken from a book issued to a customer who was then named Miss Boyle.’

Margaret gasped. He had stolen her chequebook to carry out his fraud!

Next, their old landlady, Mrs Campion, testified about the unpaid bills and the cost of the smashed electrical fire that they had left behind at 58 Pembridge Villas. ‘Captain Rambo assured me the money had been sent, but I never received anything and the amount is still due,’ she said. ‘I also wrote to Captain Rambo’s wife.’ As she spoke she caught Margaret’s eye.

Margaret felt her cheeks go red. She wondered if the whole court thought she had known of her husband’s crimes and had been in on them.

Luigi Martini, head waiter at Kettner’s, the restaurant where she and Lawrence had gone for their very first date, was next to point at him across the courtroom. ‘That is the gentleman I served,’ he said, in a thick Italian accent. ‘His food and drink bill came to five pounds, sixteen shillings and sixpence, and he gave me a cheque.’ Once again it was from Margaret’s chequebook, and had been returned marked ‘no account’.

Finally, it was Margaret’s turn to speak. She took the stand shakily and was sworn in, and was asked to explain her relationship with Lawrence.

‘I met Lawrence Rambo on 25 December 1942, and we married in October 1943,’ she told the court. ‘Our daughter was born in December.’

‘What did you know of his financial situation?’

She hesitated. ‘I knew that his financial troubles were worrying him, because he couldn’t sleep and he drank too much.’

‘And how did he seem to you in his state of mind?’

‘He was restless and nervous,’ she said. Then, fighting back a sob, she added, ‘He seemed to be a different man from the one I knew.’

‘Thank you, Mrs Rambo. That will be all.’

She returned gratefully to her seat.

Lawrence had failed to enter a plea in response to the charges, and Margaret wondered what on earth he was going to say to explain himself.

As he took the stand, he looked contrite and his brown eyes glittered as if he might be about to cry. He read from a written statement, admitting all the charges against him and throwing himself on the leniency of the court. Lawrence explained that during his years in the Canadian Army earlier in the war, he had fallen into drinking heavily and spending more than he earned. He had got his family to send him money several times from his bank account in Georgia. When he left the States, there had been $2,000 in the account, but now it was all gone.

‘I have never been a particularly good manager of money matters, and I can now see very clearly that I simply weakened under the strain of three years of living under conditions of excess drinking and both domestic and money troubles, and although it was very wrong and very foolish, I began to default on debts,’ he said. ‘It was then that I cashed the cheques listed against me in the charges in this case.

‘I have made a terrible mistake during the past several months, and I fully realise it. I do not know whether my nerves were affected, or what happened to my judgement, but I can thoroughly understand how it must appear to anyone who has not experienced the pressure caused by my personal finances.

‘Unfortunately for me and for my family, I have a wife and a four-month-old baby who will suffer more than I will. I hope that some punishment can be assessed against me that will enable me to remain in the Army so that I may immediately have a chance to begin paying off the money represented by these cheques, so that my wife and daughter will not be made to suffer for what I have done.

‘I appeal to the mercy of the court, but I stand ready to meet whatever sentence it adjudges against me with a humble and contrite heart, and regardless of the sentence, with a firm resolution that I shall never again give way to the temptation that put me in such difficulties.’

It was a moving speech, and Lawrence seemed genuinely regretful. Despite her shock and anger over what he had done, Margaret couldn’t help feeling sorry for him as she thought of the mental anguish he had been going through.

Nevertheless, the judge decided not to grant his request to save his job. Lawrence was found guilty, and sentenced to be dismissed from the Army. He was to be repatriated as soon as possible.

‘I’m sorry, I’m so sorry,’ he told Margaret at the end of the trial. ‘Can you forgive me? I told the judge I would never give way again, and I meant it. I’ll never touch another drop of alcohol. If you come with me to Georgia we can start afresh – as a family. Promise me you’ll follow me to America. Promise me.’

Margaret had no idea what to do. How could she trust Lawrence’s words after what he had done? But then, what kind of life would she have if she stayed behind? She had no one in England to support her, and now with another baby on the way, who knew what would become of her? She didn’t want to end up like her mother, raising her children alone, and she couldn’t bear the thought of telling her father that her marriage had ended in failure.

Lawrence’s dark eyes looked at her earnestly. Maybe he just wasn’t cut out for this war, she thought. Back in Georgia, with his family around him, things would be different. She had to hope so.

‘All right then, I promise,’ she said.