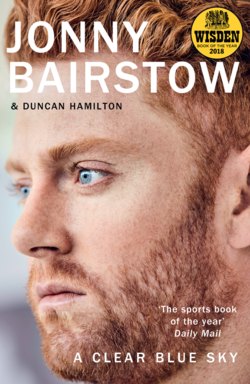

Читать книгу A Clear Blue Sky: A remarkable memoir about family, loss and the will to overcome - Duncan Hamilton, Duncan Hamilton, Jonny Bairstow - Страница 11

I THINK YOU USED TO PLAY ALONGSIDE MY DAD

ОглавлениеWinston Churchill once said: ‘If you’re going through hell, keep going.’ It sums up our family’s approach to the aftermath of my dad’s death.

Becky and I passed a near-sleepless silent night, but next morning my mum got us up and made sure we washed and scrubbed ourselves, brushed our teeth and dressed for school in our plain navy and white uniforms. She insisted that we went there, though I don’t remember either of us protesting much at all. It was my mum’s way of bringing a touch of normality to our lives, pressing on without my dad because she knew, absolutely from the start, that we couldn’t do anything else except confront, square on, the grim situation we were all now in. Already our lives had begun to change convulsively – a process that would go on until almost everything familiar to us had been rearranged or was different somehow. Knowing this, my mum came to the conclusion – and I wholeheartedly believe she was right – that we shouldn’t put off doing anything today in the hope that it would somehow seem easier to do tomorrow. The fact that it wouldn’t was the only certainty we had then. We couldn’t think or wish away reality. We couldn’t pretend it hadn’t happened.

I realise now that you survive the death of someone you love simply by living, however wrong and unnatural it feels at first and however slowly it takes for your own life to find a meaningful shape again. The first task is accepting things, which is always the hardest. In sending Becky and me to school, my mum knew that the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other, walking in a straight line and holding our heads up, would be a test for us. She also knew that it was a necessary one.

Bad news travels at an alarming rate. Ours sped like a lit fuse. Shortly after dawn broke, the first reporters and photographers arrived to lean on our closed front gate, and soon an entire scrum of them were gathered there, waiting for the curtains to twitch. Becky and I had to slip out the back door and trudge over the winter fields to get to school, which was less than 150 yards down the road. In the media’s eyes it seemed we had ceased to be people, who had suffered a bereavement and were in need of consolation. We became instead a story to be chased. That, I suppose, is the way of their world, but it shouldn’t be. It felt like a violation.

We left my mum on her birthday – her cards unopened, her presents still wrapped – to deal with the business of death while coming to terms with her own emotions, her own trauma. She went to one of her chemotherapy sessions and discovered that the newspapers, spread across a table in the hospital waiting room, were full of headlines about my dad’s suicide. The doctors, knowing of my dad’s death, had wanted to cancel the session. ‘No,’ she insisted. ‘You can’t do that to me. Not now. Not after what I’ve just gone through.’

In the coming days there were the seemingly endless formal phone calls that had to be made to sort out finances and personal affairs. There were more calls, both incoming and outgoing, to let friends know what had happened and also how, which obliged her time and again to talk about it and answer the predictable but understandably stunned questions that came next. There were the rat-a-tat knocks on the door from newspaper reporters and well-meaning neighbours alike. There were the arrangements for the funeral.

My mum and dad had been married for almost ten years. The two of them, each recently divorced, originally met in a pub in Ossett, a market town between Wakefield and Dewsbury. My mum had just moved into a new house. When my dad asked for her telephone number, she couldn’t remember it. One of her friends, who could, handed it over to him.

It was not the most auspicious of first dates. No roses. No soft music. No candlelit dinner. For some incomprehensible reason my dad decided to take my mum on a tour of some of his familiar drinking haunts in Bradford. None of them would ever have been confused with the American Bar of the Savoy Hotel. There was no sawdust on the floor, but one of the pubs had a spittoon in a corner – and it wasn’t there for ornamental purposes either. The evening slipped slowly downhill from there. My dad had a spot too much to drink, obliging my mum to take charge of his car keys and drive him home. On the way back he sang Dire Straits songs to her from the passenger seat.

(© Author’s collection)

A lot of women would have been washing their hair whenever he called again, offering another night out, but my mum liked his ‘cheekiness’ and also his ‘spontaneity’. He was the sort of man who’d arrange something on the spur of the moment, seldom giving her enough time to put on a smear of lipstick and her glad rags. He was a soul, she also said, who so dearly wanted to be loved, a trait that could be traced back to being raised without his mother. She saw him as a caring and giving person, always agreeing to donate his time to causes, his match tickets to those who asked for them, his advice and expertise when needed. They moved into my mum’s house until our family outgrew its small rooms. For, as well as Becky and me, my half-brother Andrew, from my dad’s previous marriage, came to live with us for a while, the three of us rubbing along without any difficulty. Andrew – 14 years older than me – was someone else I could pester with a ball. He became a County Championship cricketer too, a left-hand bat and wicketkeeper at Derbyshire.

My mum is a Bradford girl; she grew up only four miles away from my dad. She planned to become a primary-school teacher. She even went through most of the training before deciding, late on, that the police force would suit her much better. If you’ve watched either Life on Mars or Prime Suspect 1973 you’ll know that some of the male officers, especially those with a considerable number of years behind them, regarded the female members of the constabulary as useful chiefly for making the tea or typing reports. You had to be twice as good and three times as resilient to avoid being marginalised or patronised – or both. My mum remembers being pushed towards domestic-abuse cases because back then these were generally seen as being ‘a woman’s work’. She did door-to-door enquiries when the Yorkshire Ripper was still on the loose, his identity unknown, and women were cautious about venturing out after dark, and she was on front-line duty during the miners’ strike. In a career spanning 15 years, ending only after Becky was born, almost every day brought something that most of us would dread. One of her first cases was a shooting on an estate. The victim, barely alive, had shed so much blood when my mum got there that his skin was as grey as wet clay.

She was working for the traffic division – often dealing with the most grisly accidents – when she began courting my dad. Once, aware of when he was setting off for a match and the road he’d be taking to get there, she waited to surprise him, flagging down his car. My dad was chauffeuring another player, who saw only a uniformed figure coming towards them. ‘Were you speeding?’ he asked my dad irately, afraid that the pair of them were going to be late for the start of the match. My mum simply leaned through the driver’s window, gave my dad a kiss and said: ‘Have a nice day.’

Her background meant that she was used to handling other people’s tragedies. She’d spent time as a juvenile liaison officer, which demanded a particular compassion. So she’d comforted a lot of strangers who had suffered personal catastrophes; she’d been trained for that. But nothing can entirely prepare you for a catastrophe of your own – certainly not one of the magnitude she now confronted. My mum was suddenly a widow, and the responsibilities it thrust upon her – bills to pay, a job to find, two young children to care for alone – were immense. Her treatment was debilitating, sapping the strength from her body as it fought her disease. But however frail and tired she felt, and however scared she became, her first thoughts were always for Becky and me.

(© Author’s collection)

Ask her how she came through it all, and she’ll say that her police background ‘probably helped’. The trouble she saw and the situations she found herself in made her more resolute as a consequence. Then she will add, quite calmly and straightforwardly: ‘And I didn’t want to die. I had two young children to bring up …’

My mum spoke calmly to Becky and me about my dad’s suicide. She told us that he’d been ill … that his death wasn’t anyone’s fault … that she’d be there for us …

At our age we got the gist without comprehending the complications, the maze of it all. There was no formal counselling for us, no pouring your heart out to someone who would sift through and analyse your grief as though it were a handful of sand. Our family doctor made what seemed to Becky and me casual house calls. The doctor pretended to us that he’d simply been ‘passing by’, but of course everything had been prearranged with my mum. Becky always made him a cup of tea. He’d then start to chat to us, working out whether we needed anything more from him.

I didn’t want to go through counselling. My preference was not to speak of my dad’s death. So I didn’t. That was my way of coping. I had no intention of forgetting my dad or pretending he’d never existed. I loved and missed him too much for that. But I did, so badly, want to shut out the horrific circumstances of his passing. I put them somewhere in my mind where I hoped I wouldn’t run into them every day. That, of course, was impossible. For sometimes thinking of him meant also thinking about why he wasn’t with me – on Father’s Day, and on his birthday and my own, which were only 25 days apart.

With my dad gone, I made a resolution to myself.

I would become the man of the house. Adulthood was still more than a decade away for me. My bedroom walls were covered in posters from Gladiators, the TV show I never missed on a Saturday teatime. But I considered it my duty nonetheless to grow up and mature overnight – and get serious about doing so. I owed it to my mum. I owed it to Becky too. I would do whatever was needed around the home. I would look after my sister, being a genuinely protective big brother to her. I would anticipate my mum’s needs as much as I could, making sure I gave her as little to fret about as possible. I’d graft as hard as I could, both in the classroom and on the field. I’d make my mum proud of me. Most of all, if I had to cry, I swore to myself that I’d do it privately, where no one could see or hear me. If I found it necessary to grieve, I’d be quiet about doing so. I’d hide my hurt – just as my dad had done. And that is what I did, telling no one of my intentions. My mum remembers the two of us being in a neighbour’s house very soon after my dad had died. We were standing in front of a window and staring across their garden. I looked up and said sombrely to her: ‘Don’t worry, Mum. We’re going to be all right.’

And so we were …

The wretchedness of losing a parent when you’re so very young isn’t confined to the sorrow alone. What’s also denied to you is the chance to talk to them about their past, all the history that’s wrapped up in photo albums and keepsakes, collected and stored away. In my dad’s case, I’m thinking about those simple, taken-for-granted questions. About his own boyhood and his school days, the house he lived in, the grandpa I never met and the roots of his own extended family, the places my dad saw and also wanted to see, the hopes he had.

As a child, you barely think about any of this in a constructive way. You might throw in an occasional ‘what was it like at school during your day, Dad?’, but you certainly don’t think it’s necessary to sit down there and then and talk about the time before you were born. The long years to come are earmarked for that.

I was lucky in one regard. At Scarborough, during the mid-1970s, my dad met the man who would become his best buddy. His name is Ted Atkinson, and it’s a sign of how much he’s a part of our family that Becky and I call him Uncle Ted. He spoke at my 21st birthday party and then at Becky’s too. Uncle Ted and my dad were born in the same year, only months apart. He’s also an only child. They shared the same sense of mischievous humour and the same generosity of spirit, soon becoming as close as brothers. The two of them could be a hundred feet apart in a crowd, but be able to detect from facial expression alone the mood the other was in and what he was thinking. I know Uncle Ted thought everything of my dad, a hero to him. I know my dad loved and trusted unequivocally Uncle Ted, someone with whom he could be himself – and also someone always prepared to tell him an unvarnished truth or two, their friendship prospering because of it.

Uncle Ted says my dad was a great bunch of blokes, which encapsulates the different sides of him. That hoary term about ‘not suffering fools gladly’ certainly applied to Dad. He abhorred impoliteness, for a start. If someone approached him rudely, butting into a conversation or yanking at his arm to get his attention, he’d unhesitatingly, but very quietly, tell them to ‘piss off’, which was reasonably mild for someone who had a master’s degree in Anglo-Saxon vernacular on the field. But if he saw or heard bad behaviour off it – swearing in front of Becky and me, for example – he’d disarm the offender with an ‘excuse me’ and the sort of stare that could crack sheet-ice. Uncle Ted was always aware, well before it happened, when my dad was getting a bit riled this way. There were certain ‘tells’ in his body language. His head went up, his spine stiffened and he’d puff out his chest.

He was nevertheless much more sensitive and occasionally much more studious than any casual acquaintance – or even some of the people he played with or against – can ever have appreciated. Uncle Ted recalls my dad fretting to the extent of pacing around endlessly in circles over the plight of our kitten, which refused to come down from a tall tree after the dogs scared it. He recalls him being unable to wring the neck of a pheasant, winged during a shoot. He also recalls him refusing to budge from a spot directly in front of the television on the afternoon of Nelson Mandela’s long walk to freedom, his release after 27 years in jail. He swallowed up every last second of it. ‘Don’t you realise,’ he’d say with feeling to anyone he thought wasn’t paying due attention, ‘that this is a momentous occasion … and the sacrifices Mandela has made are momentous too. You have to watch it.’

My dad walked in the spotlight, a natural performer in the glare of it, but he would have been equally at home with anonymity. Uncle Ted makes his living predominantly as a farmer in the Yorkshire Wolds. When my dad first saw his land he pointed into the far distance and told him: ‘I could peg a tent there and be content for the rest of my life.’ Uncle Ted knows he wasn’t kidding. My dad would gladly have opened the tent flap every morning to find fields ripe with crops or ploughed into brown ridges like strips of corduroy. If two hares were boxing in front of him, so much the better.

He also regularly hobnobbed with celebrity and aristocracy, but hated anything pompous or stuffy. He became pally with John Paul Getty, who took him back to the lounge of his London flat for a drink. The flat was about the size of a South American country and full of Persian rugs and old-master paintings. Getty rang his butler to get my dad a drink. The butler had to walk about a hundred yards to reach them, the sound of his well-shined shoes eventually audible across a long corridor. He came into the room to open a cabinet that was within arm’s reach of my dad’s chair. ‘Blimey,’ my dad said. ‘I could have saved you the trouble and poured my own.’

He still much preferred to share the company of the old retainers of agriculture, gossiping with them to learn the small ways and the secrets of the countryside. In the beginning he chose to do so unobtrusively. He managed this for a while on Uncle Ted’s farm, never mentioning his own career, until one of the men finally said to him: ‘Ee lad, do yer know yer look an awful lot like that cricketer David Bairstow?’

I knew almost nothing about my dad’s career when he died. I eventually picked through his past and pieced it together from old newspaper and magazine cuttings and copies of Wisden and The Yorkshire County Cricket Club Yearbook. My favourite story soon became the first ever told about him as a cricketer.

His Championship debut for Yorkshire – against Gloucestershire at Bradford in early June 1970 – seems even now like one of those Boy’s Own stories, too fantastically neat and dramatic to be true. He was only 18, about to vote for the first time in a general election that was only a fortnight away. But there’s a photograph of him, sitting a few months later in the pavilion at Worcester, in which he looks about two years younger than his age. His sleeves are rolled and he’s hunched forward, self-consciously staring up at the camera as though reluctant to look straight at the lens. Apart from his ridiculously long sideburns, which were fashionable then, he seems wide-eyed and a little nervy, unsure of the etiquette of being a first-class cricketer.

(© Author’s collection)

Most children need convincing that their parents were once young. It doesn’t seem possible. By the time I was born in 1989, my dad was the weather-beaten combatant. He had been for a long while. He carried the visible battle wounds of cricket. His nose had been broken 15 times, the bridge flattened. A cheek had been compressed. There were various other dents, gnarls and scars that cricket had inflicted on him too, the collateral damage of his honourable profession. He didn’t complain but carried them proudly, each sparking a story that became benignly exaggerated with each telling, I suppose. So the photo at Worcester is a collector’s item, evidence of how he’d once looked.

When the call came to play for Yorkshire, he was sitting in his school library, revising for his A levels. My dad misunderstood the message he got. At first, he thought he’d been picked for the second team. After the penny dropped, he went out to celebrate, downing two pints before summoning the courage to go back and knock on the headmaster’s door. He sucked on a packet of mints, masking the smell of the beer on his breath, and told him that the match clashed with his English literature exam. Was there a possibility of bringing his exam forward? He awoke at 6 a.m., unable to eat breakfast. He sat the exam at 7 a.m., tackling the poetry of Milton and Marlowe and the novels of Graham Greene, in a draughty church hall near the school. At 9.30 a.m. he was driven to the match. At 9.45 he was standing beside the main gates, leaving tickets for his father, when Geoffrey Boycott arrived.

‘Hello, David. Will you carry this?’ said Boycs, handing him his bag. The two of them walked to the dressing room, where Boycs chose his spot and told my dad to put the bag down beside it. ‘Thank you,’ he said to him. ‘You can go now.’

My dad gave him a baffled glance, unsure about whether this was a leg-pull. ‘But I’m playing,’ he replied. Boycs then gave him a baffled glance, equally unsure about whether he was now the butt of some small practical joke.

My dad took four catches in the first innings and another in the second. Yorkshire still lost to the team that finished bottom of the table, which says a lot about the great and sudden change in fortunes at Headingley that season.

A potted history lesson is necessary to explain how my dad got into the side, the challenge he faced to stay in it and why Yorkshire spent so much of the next 20 years in strife, mostly arguing among itself.

My dad’s chance came because the team was in a state of flux. The 1960s had certainly swung for Yorkshire, always on an upward curve. They’d been champions six times, including a hat-trick of titles starting in 1966. They also won two Gillette Cups, then the premier one-day competition. This was the team of all the talents. Brian Close was captain for four of those Championships, and he plus Geoffrey Boycott, Fred Trueman and Ray Illingworth were the big wheels on which the side turned smoothly and ruthlessly. There were superb players around them too. In the slips Phil Sharpe had fast hands and seemed to sense an edge before it occurred, knowing too the line and carry of it; he could have taken a catch blindfolded. Tony Nicholson was an outstanding medium-quick bowler, accurate and capable of late swing, who took more than a hundred wickets in a summer. The spinner, Don Wilson, wasn’t called Mad Jack on a whim. He once batted as last man for Yorkshire at Worcester with his broken left arm in plaster from the elbow to the knuckles. He’d already hit five fours when the sixth – a straight drive over the bowler’s head – won the match. There were also trusty, reliable figures, always capable of a match-winning performance: Chris Old, Richard Hutton, my dad’s fellow Bradfordian Doug Padgett.

This side inspired a kind of good loathing based on envy and jealousy and a fervent desire to beat them, which was seldom fulfilled. A batsman who scored a century against Yorkshire, or a bowler who took a basketful of wickets, put themselves in contention for an England place. For some county players, facing Yorkshire was the next best thing to experiencing a Test.

But Yorkshire became complacent, assuming glory would always be theirs, and it led to some grievous mistakes. Trueman retired in 1968, and Yorkshire also let Illingworth go at the end of the same season after a contract dispute, which turned so gangrenous that he was told he could ‘take any other bugger’ with him when he went. The game was changing too, and, while Yorkshire remained aloof, everyone else rushed to recruit the crème de la crème of overseas stars, Garry Sobers, Clive Lloyd and Barry Richards among them. Like the Flat Earth Society, refusing to concede even the possibility of a spherical planet, Yorkshire clung to the stubborn belief that no one born outside its boundaries ought ever to wear the cap and sweater.

My dad became the stuff of Yorkshire legend, but he had to replace a wicketkeeper who was already established as such, which makes what he subsequently did even more extraordinary to me. Jimmy Binks was 19 when Yorkshire gave him his debut in 1955. He went on to miss only one match – against Oxford University – because the MCC called him into their side to face Surrey, then the champion county. Binks made 412 consecutive Championship appearances. He was part of Yorkshire’s high command, consulted by captains, senior pros and frontline bowlers like a cricketing oracle. His mind was like a filing cabinet, the knowledge stored in it accrued through canny observation and those endless summers of experience. The blunt Don Mosey, his flat, gruff West Riding vowels instantly recognisable to a whole generation of Test Match Special listeners, put Binks’s value to Yorkshire – especially during the 1960s – into crystal perspective. ‘The team would rather have seen him standing there with ten broken fingers inside his gloves than anyone else with a full complement of intact digits,’ said Mosey. When Binks quit in 1969, hacked off at only 33 years old with the intrusive backroom politics of the club, it opened the kind of hole that is neither easily nor quickly filled.

My dad, who as a boy had watched Binks from a bench seat at Park Avenue in Bradford, was daunted but not cowed. He found himself in a side that was still coming to terms with a new reality, which was the need to rebuild. He was being asked to take over from someone widely considered as indispensable, his like supposedly never to be seen again. When one bowler wanted a steer about a possible flaw in his action, which was the sort of information Binks volunteered without prompting, my dad told him that he’d simply ‘got enough on seeing the ball’ to focus on anyone else’s difficulties. He was raw, untried and clinging on to the chance Yorkshire had surprisingly given him; he couldn’t be expected to demonstrate in only half a season what Binks had cultivated during the previous 15. It wasn’t even fair to ask. If this wasn’t pressure enough, my dad immediately had to handle Yorkshire’s chairman of the cricket subcommittee, Brian Sellers.

Sellers, a former Yorkshire captain both immediately pre- and post-war, had won six titles in nine years, leading some of the greatest of the great: Len Hutton and Hedley Verity, Bill Bowes and Herbert Sutcliffe, Percy Holmes and Maurice Leyland. He was once described as possessing a ‘lust for victory’. Sellers was a disciplinarian, a dictatorial presence who’d been born and brought up in Edwardian England and maintained the code of conformity of the period. The anything-goes 1960s and then the still more liberal 1970s proved baffling for him. He seemed to consider Headingley as his fiefdom. He spoke in orders. Anyone who didn’t march to his exact tune was in trouble. My dad described him as ‘easily the most powerful and influential man in the club’. Sellers was a suit-and-tie and a short-back-and-sides man, his hair Brylcreemed with a parting straighter than a Roman road. He disliked jeans and trainers and open-necked shirts with flowery patterns.

My dad had enough going on in his life. For a start, there was the fanfare of publicity he got as a teenager, which ratcheted up expectations of him. Then there were the higher and more intense demands of the first-class game, so different from the Bradford League, where he’d played a lot of his cricket. And there was his new environment and the task of simply fitting in as a young guy around much older blokes.

Sellers could have cut him some slack. Instead he was confrontational, concerned as much about my dad’s appearance as his performances, a matter someone more supportive and more sympathetic might have let slide for a week or so. One morning he told my dad to get his hair cut. The next, seeing him again, he asked why it hadn’t been done. My dad made some wishy-washy excuse – based around the fact he didn’t have a car – in the unrealistic expectation that Sellers would forget all about it. He didn’t.

‘I’ve made an appointment for you,’ Sellers said, giving him the name of a barber’s. He paid the bill in advance. He also gave the barber ‘strict instructions’ not to spare the shears. My dad came out looking like a ginger billiard ball. Sellers checked up on him, growling his approval at what he saw. ‘Tha’ looks like a lad now,’ he said. It wasn’t so much what Sellers did – Yorkshire have always been strict about looking the part – but the way he did it, apparently never comprehending that his brusqueness could have been off-putting.