Читать книгу Blue: All Rise: Our Story - Duncan James, Caroline Frost, James Matthews Duncan - Страница 6

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

‘ALL RISE’

Beginnings, Meetings, Becoming Blue

19 May 1999 – Granada Studios, Manchester

ANTONY

Simon Cowell’s voice had that special tone to it even then, like he knew something the rest of us didn’t. We were nine lads who thought we pretty much knew it all, waiting to go on stage, sing live on air and make a little bit of pop history, being plucked for stardom on … This Morning. As you do. But, as we stood behind the curtain listening, and he started spelling out his expectations, we all started to go a bit quiet, and even that joker I’d just met, little Lee with his fringe, stopped horsing around for a minute. Suddenly, it had all got a bit serious.

Lovely Caron Keating, a very familiar face who’d been extremely nice to all of us since we’d arrived that morning, had asked Simon Cowell exactly what he was after. Without hesitation, he explained, ‘There’s got to be a chemistry there, you’re trying to find people with star quality. All of these guys, I presume, can sing and dance, but that little extra something …’

No pressure then, lads, and if we’d known who he was, or would go on to be, we might have been even more nervous. But Simon Cowell wasn’t Simon Cowell back then; he seemed like just another music industry exec. in a baggy, checked shirt, with a big grin and a pretty special haircut. It was Kate Thornton sitting next to him who was actually more intimidating; after all, Smash Hits was our Bible growing up and she’d been its editor. And, never mind all that, we were about to appear on This Morning, the show we’d all watched for years, as it set about creating its very own boy band.

We’d all got through previous auditions to get this far, but this was different: we’d be singing live on TV, no backing track, no musicians, just our voices in all their naked glory … or instantly apparent lack thereof.

Despite Simon Cowell’s certainty that day about exactly what it was he was after, it seems only right to point out that it was actually Kate Thornton who first mentioned the phrase that would go on to launch a billion-dollar franchise on both sides of the Atlantic and would turn Simon into the global TV powerhouse he became. She said: ‘It’s an indefinable X factor that sorts out the wannabes from the superstars and that’s really what we’re looking for.’

Bang! See what I mean about falling into history? Little did we know … It’s really hard with hindsight to say if any of those waiting behind that curtain had that ‘je ne sais quoi’ they were going on about, but it was a motley crew indeed. There were some faces I already knew, and others whose paths would later cross ours for years to come. There was Declan Bennett, who used to be in a band called Point Break before he later turned up as Charlie Cotton, Dot’s grandson, in EastEnders. Another lad was Andy Scott-Lee, who later appeared on Pop Idol and made it all the way to the final. His sister Lisa was also in Steps. Those wannabe tiers of the pop industry made for a small world in those days, with everybody knowing everybody else, usually from queuing up for hours together at different auditions. Two people stood out for me. One was a lad from Exeter called Will Young, who seemed pretty confident in two vests and big trainers. He stood up tall and looked everyone straight in the eye, and he sang an excellent version of ‘I’ll Be There’, getting his voice nearly as high as Michael Jackson’s. The other one was that joker I told you about, a bloke called Lee Ryan, who I had a laugh with, talking about our favourite TV programmes. He had blond curtains for a haircut, and was wearing a suit! He looked like a dodgy best man or a car salesman, and that suit was easily two sizes too big for his adolescent frame. He told everyone he was 16, but I wasn’t exactly sure about that.

LEE

Okay, so I was actually 14, but I always liked a suit. For this audition, I’d chosen an impressive silver number, only slightly too large, that I’d found in a Greenwich clothes shop. Funnily enough, behind the counter that day had been one Dave Berry, later to follow his own star in the entertainment industry.

I hadn’t actually applied for this audition myself, it had been my Aunty Joan who’d sent my demo off on my behalf, and she’d fibbed about my age. But I’d been to stage school so I wasn’t nervous about performing at all, so I was getting ready to sing ‘Swear It Again’ by Westlife. Out of everyone there, I got on best with Antony – we didn’t stop talking, and he was making me laugh, which is pretty much all that matters at that age, right? Then he went on before me, and I heard them ask his name, and he said, ‘Michael from Edgware’ and I thought, ‘Hold on a minute, is anyone here actually telling the truth about themselves?’

ANTONY

To this day I can’t explain what happened there. The only reason I can think of is that my chosen song was ‘Outside’ by George Michael, and I got a bit tied up in knots. Anyway, I started singing. No, YouTube doesn’t lie … Yes, I was wearing a shirt long enough to be a nightdress, and white baggy chinos. And if that look was a bit too ordinary for the judges, they couldn’t fail to be bowled over by my enthusiastic headshakes and some serious thumb action. All those hours in front of the mirror had not been wasted.

Except they had! At the end they called out some names, and you may be amazed to learn that neither the thumbs nor the rest of my performance made the cut. Lee did get through (as did Will Young), so I wished him luck, we swapped numbers and said we’d stay in contact.

LEE

Nothing much happened with the band, although it obviously planted a seed in Simon Cowell’s brain. The whole idea of forming a boy band live on TV like that hadn’t been done before, but he saw all the potential, took that concept and ran with it. We just happened to be there on day one and become his accidental prototypes.

More significant for me that morning, as it turned out, was making a friend of Mr Antony Costa. We stayed in touch, more than you’d expect teenage blokes to bother, really, keeping tabs on each other’s progress, sharing tips for auditions, having a laugh. And then, two years later, I got a phone call, and it seemed our paths were about to cross once more …

ANTONY

Have I mentioned George Michael already? He was my hero, the backbone of my musical education growing up – him, and Cabaret, naturally. I was pretty ordinary at everything at school – the teachers knew it, I knew it – but I didn’t mind, because that was the musical they put on one year – a bunch of 14-year-old North Londoners acting out the tale of a 1930s’ Berlin nightclub against the background of the Nazis’ rise to power. It seemed completely normal at the time. Not sure I got every single subtext in the story, but I certainly caught the singing bug, and that was it, I’d found my thing.

Occasionally, I could be prised out of the house for a football match with my mates, but otherwise, I spent all my downtime hollering into my hairbrush in front of the mirror. Of all the stars of the day, for me it was always George, which, as a fellow Greek lad from North London, seemed only right and proper. Which meant that the locals in pubs around Edgware, Stanmore and Barnet were treated to more than their fair share of ‘Faith’ and ‘Father Figure’ when I turned 17 and started my own tribute act. Yes, you read that correctly. And if you should have happened into Edgware’s Masons Arms of a Friday night around that time, you would no doubt remember being treated to the sight of a wobbly but keen singer in the corner – double denim and aviator glasses, the works.

By then, I was always reading The Stage, and always gigging. I saw it as my apprenticeship. It’s all changed now, of course – these days, you can go on X Factor and, if you play your cards right, become a star overnight. That’s obviously great, a massive shortcut, but if you don’t have to put in the hard yards to learn your trade, I’m not sure you appreciate success in the same way when it does come. And you’d definitely miss out on the fun of the early days. Come on, who wouldn’t want to wear double denim, singing to seven people, and possibly a dog, in the Masons Arms of a Friday evening?

For me, if the wind was blowing in the right direction and blew some generous types through the doors, I’d make £50 for my pains and I thought I was winning. And then I got blown in a fortunate direction myself. I used to like practising my new songs by doing karaoke, which was how I ended up in a bar called The G-Spot in Golders Green. They had karaoke every Friday, and this bunch of lads I’d never heard of used to turn up for the same reason. I’ll be honest, I thought they were all a bunch of berks, ripping their tops off and posing around, but one of them was always polite and much nicer to me than the rest.

DUNCAN

My friends in North London always suggested we went to The G-Spot on Fridays, because that was karaoke night. And we’d be there, hanging out, and there was this lad called Antony doing his thing, and they just weren’t sure about him. I really liked him, used to talk to him whenever I saw him, but they thought it was weird, him turning up every week with his dad.

ANTONY

My dad used to come with me because I couldn’t drive. I was still only 17. My whole family knew what I wanted to do, and as far as my dad was concerned, if it meant I wasn’t hanging round street corners and starting trouble, he’d support me in all of it.

He even bought me a PA system for my birthday – a microphone, amp, sound-desk, the works – and started doing the sound for me whenever I got a gig. Bless him, he was absolutely useless, but we did have a laugh.

DUNCAN

I used to like that about Antony and his dad, the idea of them sticking together. I used to watch them joking, trying to work their equipment, and, in fact, it touched me more than he would have realised, because I’d grown up without a father, and I’d recently lost my grandfather, who’d always played that role for me.

My mother brought me up on her own and she was away a lot, working shifts as a nurse, so I spent huge amounts of time with my grandparents. Grandpa was the most important man in my life growing up, so I was lucky he was such a special person. He’d been a colonel in the army before he retired and became a music teacher, so as well as everything else he did for me, he introduced me to music. We lived in Blandford Forum, an old army town, and every weekend, Grandpa would play the piano in the church at the garrison, and I got to go with him. For a seven-year-old, it was the highlight of my week, driving up to the gate, where the guards in uniform asked to see Grandpa’s pass, which said ‘lieutenant colonel’. Then they saluted him, raised the barrier and we were through. It was unbelievably cool, and then I’d sit next to him in the church, while he played.

I’d played the piano myself since I was four, he made sure of that. But despite Grandpa instilling his own love of tunes in me, I wasn’t really allowed pop music in the house – Grandma said it used to hurt her ears. We had a really old stereo, and I used to sit tucked away in the corner, hoping she wouldn’t notice I was listening to the Top 40 with headphones on. Kylie Minogue was my favourite – I had a poster of her on my wall. No, I’m not expecting this to surprise you. The benefit of hindsight, eh?

Ours was a pretty religious household – my first performances as an altar boy remain among my best work – so I thought I’d pulled a masterstroke with the first ever record I bought. How could Grandma object to Enigma with all that Gregorian chanting at the beginning? I did get to play it a couple of times before it was whisked away.

The only thing more glamorous to me at the time than organ bashing at the garrison was Butlins, where my mum took me on holiday when I was little. Hi-de-Hi was my favourite television programme, and I was in love with Su Pollard. I adored the Redcoats and was determined to be one myself. And I managed it, reader, signing on for singing duty with Haven Holidays in Bridport and staying for a year. I loved it, especially dressing up as a cat and singing ‘Memory’. Fine times!

As with the others, The Stage magazine was my Bible, and I used to audition for anything I spotted. I was pretty lucky, getting into two bands in swift succession, which meant moving to London.

The first was a boy band called Volume 5, which, you’re right, sounds like a hairspray. We lived in Oxford Street in bunk beds in our manager’s apartment, and were – how to put this nicely? – shit. But we were all together and the most exciting thing we ever did was turn on the Walthamstow Christmas Lights.

My next band was Tantrum, three boys and two girls, built on the whim of a rich man who wanted us to sing songs for his girlfriend. There were some familiar faces in the auditions – Myleene Klass made it to the shortlist – as well as in the final line-up. Among us was Rita Simons, who played Roxy Mitchell in EastEnders, Ziggy Lichman, who went on to be in the band Northern Line, before turning up as Zac in Big Brother, and a bloke called Jonas. Years later, I turned on Channel 5 one day and there he was, reading the news. It’s a comfortingly small world.

I was in Tantrum for a year, and we got paid a weekly wage. But we soon realised it wasn’t going anywhere, and both my grandparents died during that time. We all knew it was time to move on.

With the money my grandparents left me, I was able to put a deposit on a house in East Finchley and buy myself a bit of time to come to terms with my grief over losing those people so dear to me in such swift succession. I worked as a barman at the Old White Lion in the evening, while by day I was a perfume salesman, standing in the door of Selfridges and spraying people as they walked in. Those two jobs meant I had time to carry on going to auditions in between, and one of those auditions was for a brand new band being put together by someone who sounded like he knew what he was doing.

LEE

Daniel Glatman was a bit of a geek (sorry, Daniel, but you were), very young, but definitely a man on a mission. As he later told it to us, he walked into the record label’s offices, announced, ‘I want to put a boy band together,’ and the boss at the time, Hugh Goldsmith, replied, ‘Okay, go find them, bring them back, and here’s £10,000.’ Why can’t everything in life be that simple? It was only later Daniel revealed to us that what had actually happened was that he’d somehow blagged his way into Hugh’s office, talked a good game until he was blue in the face and eventually been given three months to put a band together, or he’d have to pay the money back.

I’d grown up going to performing arts schools, good ones like Sylvia Young’s Theatre School and the Italia Conti Academy of Theatre Arts, thanks to my mum. She had spotted my singing potential very early on, and she’d been keen to give me the best possible chance at a creative future. I was pretty fortunate in that way – one day, she even spotted me doing my homework, told me to stop because she said it was more important that I learned the harmonies to ‘Endless Love’. It turned out she was right. Years later, I ended up sharing the stage with Lionel Richie, singing another one of his classics, ‘Easy’, so I guess my mum pushed me in the right direction, encouraging my love for all things Motown.

Something else she passed on to me was being a big softy even as a teenager – I once gave away a pair of new shoes to a bloke at a tube station and my mum didn’t even tell me off – but I was also pretty headstrong, certain that I knew it all. I’d walked out of school aged 15, thinking I’d learned everything I was going to need – somehow, I had a good idea that algebra wasn’t going to feature largely in my future. I wasn’t afraid of work, and used to make my money with all sorts of jobs – on a stall, on a roof, anything to make a pound note. But the musical seed had been sown, and I also used to go every week to the newsagent to pick up my copy of The Stage.

It’s so strange to talk about, now everything and everybody is available on the internet, but back then, if you didn’t have an agent, reading the ads at the back of The Stage was the only way to spot what was going on, and for management and record labels to find you. That’s how bloody old we are!

DUNCAN

I’d sent in a picture and a demo tape, and was invited in to meet Daniel. He was young but looked older, and seemed intent on doing well in the industry.

People seemed to be trickling in and out all day. I got up on stage and sang ‘Can’t Help Falling In Love’ by Elvis, and then channelled my inner Redcoat with Michael Ball’s ‘Love Changes Everything’. Not perhaps the most cutting-edge choices, but hey, I got a call back and was invited to a singing lesson, where I spotted my old pal Antony, and met Lee again. We’d crossed paths at a previous audition but hadn’t really talked.

My first memory of Lee that day was of his massive, brick-sized phone, and he was arguing with somebody on it. That call obviously ended badly, and he went bonkers, head-butted the phone and then threw it on the floor, where it smashed into a million pieces. He stared at it for a minute, then he looked at me and said, ‘Can I borrow your phone?’ I guess he started as he meant to go on.

He was very smartly dressed, though – I’ll give him that – all nice jeans, smart black shoes, Ben Sherman shirt … My influences had been my skateboarding pals back in Devon, so I had a bit of a baggier thing going on.

LEE

Duncan had on some truly dodgy shirts. He was a bit of a hippy back in those days and his dress sense was terrible – who wears tracksuit bottoms to an audition? Has it improved now? I’m always optimistic. With Dunc, though, it was all about the hair. There was loads of it, hanging over his face, as this little pretty boy was sitting in the corner. He looked a bit stand-offish, but he was probably just shy. And he wouldn’t lend me his phone.

ANTONY

Daniel was happy that Duncan and I already knew each other, so that worked in our favour, and we were the first two to be picked. Then he asked Lee to join, plus two other blokes, Richard and Spencer. Richard was actually one of the lads Lee and I had met during our appearance on This Morning. As well as sharing that strange baptism of fire, he was friendly, very funny, and we all got on well with him. Spencer was a bit more competitive, and, being young lads, we butted heads with him occasionally. Don’t get me wrong, he was a nice enough lad, but we just never really clicked.

DUNCAN

The three of us became really tight with Richard. One of the best times was when we spent a weekend at his family home in Westbeach, where we went out together on jet skis, sang karaoke in a local bar and his mum cooked us all lovely food. They couldn’t have been more welcoming, and Richard was incredibly good fun, really engaging. But I can’t say we connected with Spencer in the same way. However, despite most of us getting on so well, it just didn’t work. Something about that line-up simply didn’t feel right, but none of us said anything, until the day came for us to sign our contract with Virgin Music [10 September 2000].

We were literally in the car on the way there, my phone rang, and it was Daniel. He said, ‘We have a problem. You, Lee and Antony need to get out of the car, make an excuse and get here by yourselves without the other two. I don’t know how you’re going to do this, but you’ll find a way …’

It was ridiculous. I had to make up some excuse about the lawyer not being happy with the contract, saying it would happen the next day, while I was frantically texting Antony and Lee and telling them to meet me up the road. Somehow, the right people got to the Virgin offices, and our management was waiting. They put us on the spot, saying, ‘We love you three, but we weren’t happy with the other two. If you’re happy to sign, we can make this work, with someone else. Are you happy to sign?’, with the pen hovering in the air.

Friendship has always been really important to me. Because I’m an only child, my friends are my extended family. The idea of letting Richard down like that was terrible, and Antony and Lee felt the same. Funnily enough, we weren’t so bothered about Spencer – he’d been a cocky time bomb waiting to go off, and we’d already had a word with the manager about him. But Richard’s abrupt exit made us feel awkward. However, at that point, you’re also feeling so grateful that it’s not you they’ve cast away, that they want you, not somebody else, that you just think about yourself, horrible as it is.

LEE

I know what you’re thinking: if somebody being too cocky was the problem here, why was I still in the band? Well, I have to be honest, I think wearing a cap saved me. Bear with me …

I used to wear caps all the time I was at school, and one thing I learned pretty fast was, when you’re in trouble, put your head down and shut up. I knew those two guys, Spencer particularly, were overstepping the mark. One day, Hugh Goldsmith walked into a meeting with us, and they started talking over him, and I saw his face change, and I just knew. I thought, ‘That’s it, it’s all over,’ and I pulled my cap down, put my hands in my pockets and just shut up. Which proved to be the right decision, because almost the very next day they were out. (Perhaps I should have made sure I was wearing a cap the day we were interviewed by The Sun about 9/11, but that’s another story … And the whole time I was in the Celebrity Big Brother house, come to think of it, but that’s another story, too.)

DUNCAN

So we signed with our hearts in our mouths, and set about trying to find a fourth member. But it proved to be more difficult than we’d thought; we just couldn’t find anyone that fitted. We had auditions at Pineapple Studios in Covent Garden, with loads of people coming in from everywhere. It was like The X Factor and we were the judges. We got the giggles frequently, with Lee disappearing beneath the table sometimes, but laughs aside, we started to run out of ideas. And then Lee remembered his housemate. One day, he walked in and told us, ‘Simon needs to be in the band, he’s great.’

SIMON

I’d first met Lee at an audition for another band, ages before, and Duncan had actually been there, too. The very first time I walked into a room with them in, Lee was playing pool and being loud and boisterous. ‘He looks like trouble,’ I thought. (Sorry, Lee!) And Duncan was sitting on the floor, legs crossed, with floppy hair covering his face – the whole Brad Pitt-a-like thing going on. And then he started singing, and I noticed his husky voice, and then it was Lee’s turn and I thought, ‘Wow, I want to be in a band with you!’ Nothing came out of that day, but Lee and I stayed in touch.

LEE

Simon stood out straight away because he was very good-looking. It was no surprise for us to learn he was also a model. His body was ridiculously toned, and he had this bleached blond hair. You just knew when you met him that he had this star quality about him. He still has it, but we’re a bit more used to it now.

SIMON

I was at a bit of a crossroads in my life that day. Back in Manchester, the year before, I’d won a modelling competition for Pride magazine, which meant I had a contract, but I had to move to London to be able to start work. I had a girlfriend back home at the time, so I was torn between the two. I’ve always been independent, and one day a friend said to me, ‘Sometimes you have to be selfish to be kind to yourself. You have to be prepared to move on.’ And that was exactly what I ended up doing. But it was hard.

However, I didn’t join the music industry on that particular day, but I made friends with Lee – who, as I discovered, wears his heart on his sleeve, is very generous and impulsive, but sometimes doesn’t have a very good memory. I’d just lost my grandfather and was back in Manchester licking my wounds when he called to see how I was doing. I told him I needed to get to London, but I couldn’t work out how I was going to pay for it. Next thing I heard was, ‘Just move in with me. My sister’s moved out, you can have her room.’ ‘What will your mum say?’ I asked. He said she’d be fine, and I remember saying, ‘Oh, will she? We’ll see.’

LEE

Yes, I forgot to mention it to my mum until I got a call from Simon a couple of days later to say he’d got to Charing Cross and would be catching the next bus to Kidbrooke. So, at that point, I thought I’d better say something.

SIMON

Much later, over a cup of tea, Lee’s mum told me her version of events, which was that he’d said to her, ‘Remember that guy from Manchester you used to speak to on the phone? Well, I’ve told him he can move in.’ She said, ‘What do you mean, for how long?’ And Lee said, ‘He said, he’ll see.’ She must have thought she had a right cheeky one on her hands. But we got on very well – I kept my room nice, and Lee’s mum is one of those special people who puts into action her belief that when you’re in a position to help people, you should. We became a cosy little unit, and I ended up staying for six months before I’d saved up enough to move into my own place. I got a job on Scrubs Lane, right across on the other side of London, so my travelling started at six in the morning. I like my sleep, and I was 10 minutes late every single day. But I was also writing songs in my head – during that time I wrote ‘Bounce’, which ended up on the first album [All Rise], and ‘Flexin’ which appeared on the second [One Love]. I had a job, I was living in London, I’d started my new adventure, and so I was pretty happy.

Then Lee got a call from his mate Duncan about auditions for a brand new band, and he asked me if I wanted to come along too. I was worried, and asked him, ‘What if I get in and you don’t? I’ll feel really bad because you’ve helped me out so much already.’ His mum was listening to our conversation, and later she said to me, ‘Thank you for not jumping on that, like so many people would, you’re a true friend to my son.’ And I was, as he was to me.

It turned out no one needed to worry about split loyalties. Lee was straight in as soon as he started singing, but I didn’t get along with Daniel Glatman the way the others did. He was a great bloke, but we just didn’t gel. He was only a couple of years older than me, and I still had a lot of Moss Side attitude. I found it really difficult to even listen to what he was saying, let alone follow his instructions.

So that was that, Lee was off with the rest of them, and I sat back to lick my wounds until a few weeks later, he came home to say the line-up had changed and now it was just him, Antony and Duncan, while they looked for a fourth. He tried to persuade me to go again, but I told him, ‘I don’t think so, man, that’s not going to work. I’ve already burned that bridge, sorry.’

LEE

They tried out all sorts of different people, including one bloke who was perfectly nice, but he was even younger than me, and I just kept thinking Simon would be better. I admit a part of me was thinking, ‘Hang on, I want to be the baby.’ But I knew Simon would be great – he wanted to be in a band, he was always writing songs and asking me for techniques on how to improve. Whenever we practised together, I could hear he had this amazing tone; there was real natural talent there, he just sounded unique. I heard it and, young as I was myself, I could tell there was something special there that could be developed if he had the right people around him. So I was crossing my fingers.

SIMON

I’d made some other friends in London by then, and I was hanging out with a girl called Ruth – just friends, but very close. And a couple of days after my chat with Lee, she called me. She said, ‘A friend of mine is a producer, and he’s working for this new band at Virgin. They’ve already got three guys, and they’re looking for a fourth. I’ve suggested you – would you be interested?’

She had no idea I was living with Lee. These were two completely different pathways that led to the same place. Of course, when Lee heard that, he thought the stars had aligned and it was all meant to be and I must admit, I was pretty persuaded by it myself. So, I headed off for another meeting with their manager, Daniel, and the first thing I did when I arrived was to apologise to him for getting off on the wrong foot.

He looked at me for a while, and then he said, ‘You’re being a man for saying you were wrong, so why don’t you sing something for us?’

‘Sure,’ I said. ‘Anything you like.’

And he gave me ‘Flying Without Wings’.

‘You have to be joking,’ I said. ‘This is Westlife.’ And off I went again. ‘I don’t like Westlife, blah blah …’ Sometimes I just can’t help myself. But this time he decided to overlook it.

Antony was the last person I had to meet and he had the final say. Of course, Duncan and Lee had been building me up and Antony, being typical of the man I now know, was resisting it purely for that reason. ‘Well, I’ll see when I meet him. I’ll decide for myself, won’t I?’

Lee had given me the heads-up that Antony doesn’t like people who look away and have a lettuce handshake, so the first thing I did was eyeball him and pump his hand like a salesman. He must have thought I was a bit strange. We were still young men, finding out things about ourselves. Meanwhile, the lady in the Virgin offices was giving me fresh problems – she’d decided my long hair made me too pretty; she wanted it cut.

DUNCAN

Justine, Hugh’s right-hand woman, actually took me to one side and said, ‘Get him to shave all that hair off, it looks terrible.’

SIMON

I’d just paid £700 for a portfolio of model shots, and they all had hair! I was thinking, ‘They want me to cut my hair off for the band, and then if I don’t get in, that’s my modelling gone as well.’ Now you may say hair grows, but … Most black guys have shaven hair, I was getting work because of my hair, it was my unique selling point. So what should I do?

I took a risk, the hair went, and I went back to the record label’s office. The same lady was there, and she did a double take, and said, ‘Yes, that’ll do.’

DUNCAN

He’s being modest. She couldn’t take her eyes off him: he had it all going on, the shades, the hair. He looked like a superstar.

SIMON

A week later, I was signed. Three had become four.

LEE

I’m taking all the credit for this, but nobody ever listens to me.

DUNCAN

We didn’t have a name for ages. Lee wanted to call us Chenise, but fortunately nobody ever listens to him. Turned out it was the same name as his mum’s hairdressing salon. For God’s sake … I liked the name Four Souls because it had depth, but Antony made the valid point that we were clearly asking to be called Four Arse Holes, or Fore Skins. Either way, it could be problematic.

ANTONY

Then, one day, we were on the Underground, on the way to record our very first song. The record company had told us, ‘We need a name, you need to come up with something.’ No pressure, people … We were struggling, and it was turning into a bit of a boring old process.

SIMON

They wanted a name that didn’t scream ‘boy band’, and I was thinking about all these top artists like Red Hot Chili Peppers, Pink, Black Sabbath, and realising they all had colours attached to them.

ANTONY

So we were on the Tube, chewing on it, and Simon suddenly said, ‘What do you think of the name Blue?’ Why? ‘Because we’ve got to get on that blue line next,’ he said. We were all a bit stumped, turning it over in our minds. ‘Blue … okay.’ Lee threw in a ‘What about Yellow?’ but we pretended we hadn’t heard.

As soon as we got off the Tube, we phoned up the record company to tell them, but they interrupted us. They said, ‘We think we’ve found the name for you, boys.’ Our hearts sank. What was it?

‘It’s Blue.’

‘But that’s our name, we’ve just thought of it, that’s why we phoned …’

But they had thought of it as well. Very bizarre …

SIMON

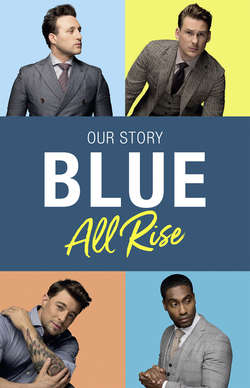

We all just looked at each other. Lee started shouting, ‘It’s a sign, it’s our destiny.’ Usually, we don’t pay him any attention when he starts going all Mystic Meg on us, but even I have to admit, something strange was going on that day. So from then on, we were Blue.