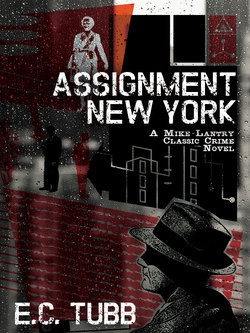

Читать книгу Assignment New York - E. C. Tubb - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

The next day dawned cloudy but dry. I hurried through my toilet, trying not to feel the cold and knowing that winter would soon be coating the streets with ice and slush. I shaved carefully over the scar and took trouble with my hair. I chose the double-breasted, grey worsted suit, one I’d had made when I’d been able to afford a really good cloth. It had a fine stripe and a faint check, and the tailor had known what he was doing. With the suit I chose black Oxfords, a white shirt, and decided on a ten-dollar, hand-painted tie I’d given myself for a birthday present and only worn once.

I tucked a silk handkerchief in my breast pocket and settled the shoulder holster more comfortably beneath my arm. From the bedside table I picked up my gun, checked the loading, then slipped the 9mm Browning into its resting place. I like the Browning and I like the calibre. Some men go in for a .45 Service automatic, others like a Luger, and one man I knew used to favour an Italian Berreta until it jammed one day when he needed it and he collected a dozen slugs. Still, each man to his choice, and I’d found that the fifteen-shot magazine gave me an edge over the boys who liked to count shots.

It also saved me carrying an extra clip.

I smoothed my jacket, the cut of the suit hiding the bulge of the gun, and slipped into my gabardine raincoat. A soft, matching grey, snap-brimmed fedora, and I was ready for breakfast.

I was also ready to visit ten million dollars.

Over a stack of wheatcakes drenched in maple syrup, I gave some thought to my midnight visitors. It wasn’t their arrival at midnight which made me think; there’s more business done between dusk and dawn than most citizens know about. No, it was why the Colonel should call on me at all. I was still thinking about it when Pug dropped into the seat opposite to me and looked hopefully at my empty plate.

‘Hello, Mike,’ he said forlornly. ‘Anything doing?’

I stared at him, looking at the obvious signs of a recent battering, and beneath my stare he flushed.

‘You’ve been in the ring again,’ I accused. ‘So much for promises.’

‘Aw, Mike,’ He squirmed as though he was a small boy instead of a two-hundred-and-twenty-pound bruiser. ‘Looie offered me ten bucks, win, lose, or draw, and I was hungry.’

That was an understatement. Pug Berson was always hungry, had always been hungry ever since he could remember. He had tried to fight his way out of the slums with his fists and fallen in with a bunch of bright boys who had thrown him to the wolves. Almost punch-drunk, desperate, ready for anything, he had been easy meat for a gambling ring who believed in making sure of winning before the bout ever started.

Pug was honest, as honest as any man could be who had come up the hard way, and he’d refused to take a fall. So, just to show him, they gave him a nice, easy, one-way ticket to the electric chair by means of a gang killing, and enough circumstantial evidence to fry a saint. A frame-up, sure, but who was to worry?

I did. I’d found the killer and sprung Pug, and he’d never forgotten it.

He never let me forget it either.

‘Okay, so you were hungry.’ I snapped my fingers at the waitress and she came gliding over. ‘Repeat order, doubled, and two cups of coffee.’ I waited until she’d brought Pug his breakfast, lit a cigarette, and while waiting for my coffee to cool, examined the photograph the Colonel had left with me.

It was a colour print, a good job, and could even be a good likeness, if you made allowance for the touching up. The data on the back read: height, 5 ft. 5 ins.; bust, 34; hips 35; weight, 95 lbs.; waist, 25; colour, blonde; complexion, fair; scars, none; other distinguishing marks, none; age, twenty-eight.

All of which made her just one of maybe twenty million women.

The face was something else. I discounted fifty per cent of what I saw, and what remained still made her something special. I could see why Geeson wanted her back.

The waitress came over and began to sweep away a few non-existent crumbs. I reached for my wallet and took out one of the brand-new bills. Her eyes almost slid from their sockets as I laid it in front of her.

‘Gee!’ She stared at the bill as if she’d never seen one like it before, which she probably hadn’t. ‘Haven’t you got anything smaller?’

‘No, crack it for me, will you?’ I stared again at the colour print, memorising it, studying the bone structure, ears, eyes, hair-line, the shape of the mouth. Faces can be disguised, but some things can never be hidden. By the time the waitress returned with my change, I could have picked out the missing woman from a crowd scene in a movie.

Pug gulped the last of his coffee and reached for the photograph.

‘Anyone I know?’

‘Maybe.’ I passed him the print. ‘Take a look.’

He did, a long one, then whistled.

‘Some dame, eh! Yours?’

‘Colonel Geeson’s. His wife. He wants her back.’

‘A powder.’ He nodded, with the wisdom of the slums. ‘Fell for some rich guy.’

‘The Colonel,’ I explained, ‘has ten million dollars. Try again.’

‘What’s the use? A dame, no kind of dame, ever runs from that kind of dough. You got to find her?’

‘That’s the general idea.’ I could talk to Pug and, sometimes, he managed to put his finger on the one thing so obvious no one would see it. ‘Try it for size, Pug. You’re a woman, good-looking, young, married to a rich guy who is liable to kick the bucket any moment. What would make you run away?’

He thought about it, screwing his eyes and rubbing the scarred knuckles of his hands. Watching him think almost made me feel tired, it was such hard work.

‘Forget it,’ I said wearily. ‘It’s no easier for you than for me.’ I reached out to pick up the print where it was lying on the table between us.

‘Hold it!’ Pug rested one big paw on the photograph. ‘I’ve seen this dame before.’ He frowned with the effort required to think. ‘At the fights. She used to run around with Thornedyke’s mob.’

‘You’re crazy!’ I snatched up the print and put it in my pocket. ‘What would a woman like her be doing with that heel?’

‘Why ask me?’ Pug looked baffled. ‘I’m sure I’ve seen her with him. Let me see,’ he stared up at the fly-blown ceiling. ‘Two years ago? Three? Hell, how can I remember?’

‘After that beating you took last night, you can’t.’ I got up from the table and he trotted after me as I headed for the door.

‘Say, Mike!’ He stood before me and I guessed what was coming. Not a touch, Pug wasn’t a bum, but he had a pathetic belief that I needed him to protect me. Sometimes I did. Sometimes his weight and brawn had saved me from a nasty beating, but I couldn’t see the Colonel’s servants ganging up on me with lead pipes and razors. I had an idea.

‘Listen.’ I took out the print and shoved it into his hand. I took out some money, ten dollars, and put it with the photograph. ‘Make the rounds. Check the hospitals and accident wards. Drop in at the morgue and ask around in the dives. She may have been taken in without identity. She may even be suffering from amnesia or something. Get around and cover the field. If she’s in trouble she may not want publicity. Find her, Pug, and I’ll cut you in a C note.’

‘A hundred bucks.’ He beamed with gratitude. ‘Sure, Mike, I’ll do it.’ He hesitated. ‘You certain that you don’t want me with you, just in case?’

‘Not this trip.’ I shoved him towards the kerb. ‘On your way, sleuth, and don’t report back until you find something.’

I watched as his big figure dwindled and lost itself in the crowd. A waste of time? Sure, but he’d come to no harm making the double-check and, for all I knew, he could strike it lucky. He wouldn’t be looking for Mrs. Geeson, of course, I knew him well enough for that. She would be his sister, his wife, his girlfriend, anything he could think of to legitimise his questions. He might even find her. Might. I doubted it.

But it got him out of my hair.

Glancing at my wristwatch, I saw that the banks would be open by now. I walked half a mile and deposited three of the bills at my bank, grinning as I imagined how the manager would be now that he could meet certain cheques without having to decide between bouncing them back or giving me an overdraft.

From the bank I caught the elevated to Osbourne Heights, changing to a cab in order to ride the couple of miles to my destination. I could have taken a streetcar, but didn’t. I’m not a snob, but I had to keep up a front, and it was lucky I did. The drive must have been all of a mile long. Paying off the cab, I pressed the doorbell and, while I waited, glanced at the weather-stained front of the big, brownstone house and the trimmed lawn before it. I was busy wondering what a convulated piece of moss-covered stone was supposed to represent when the door opened and a discreet cough warned me that I was not alone.

I handed the butler my card. ‘The Colonel probably left orders about me,’ I said. ‘Is he at home?’

‘No, sir.’ The butler glanced at the card in his hand. I’d given him one of my personal cards, the one which doesn’t say anything about my business, but I could see that he wasn’t impressed. ‘The Colonel did mention you, Mr. Lantry. I understand that you wish to question Marie.’

‘Marie?’ I stepped into a hall which could have been hired out as a taxi-dancers’ step-around, and the door swung shut with a click from its patent lock.

‘Madam’s maid,’ explained the butler. ‘I will send for her at once.’

‘Just a minute—er?’

‘Harmond, sir.’

‘You know my name already, Harmond.’ I grinned at him, and some of the ice thawed from his weak old eyes. ‘Are the children at home?’

‘I believe so, sir. Shall I inform them of your presence?’

‘Later.’ I stared at him, trying to read beyond the professional mask. Servants aren’t as dumb as most people like to think, and I’d have wagered half of what I owned that Harmond knew more of what went on in the house than the owner did. If he wanted to he could be a great help.

‘You know why I’m here, Harmond?’

‘No, sir,’ he lied.

‘But you could guess.’ I handed him one of my professional cards. He glanced at it and somehow, in some subtle way, his face altered.

‘Madam?’

‘Yes.’

‘I see. Are you connected with the official police?’

‘No.’ I stared at him. ‘I want to find her, Harmond. Do you want me to?’

‘Indeed, yes, sir.’ He seemed about to say more, then his face froze back into its original mask. ‘I will inform Marie that you are waiting, sir. If you will remain in the library I will send her to you.’

I followed him into a small, book-lined room, where he left me alone with the mouldering volumes. Marie came in just as I was wondering whether it would be best to start reading a book or to go in search of her. As soon as I saw her, I could tell that she knew what I was and what I wanted.

She was small, pretty in a hard, cynical way, and if it hadn’t been for her powder and phony French accent she would have been quite attractive. I smiled at her and offered her a cigarette.

‘Did the Colonel tell you to expect me, Marie?’

‘Oui, monsieur.’

‘C’est bon Alors, did moi—’

‘Okay, wise guy,’ she said wearily. ‘So I’m not French. What do you want to know?’

‘What clothes, if any, did the Colonel’s wife take with her when she left?’

‘None.’

‘None?’ I raised my eyebrows. ‘In this weather? She must have been pretty hot-blooded to walk naked in early winter.’

‘Joke,’ she said flatly. ‘Ha, ha, ha.’

‘Then what did she take?’

‘What she was wearing.’

‘So?’

‘Well, the usual underthings.’ She darted a vicious glance at me. ‘Want me to elaborate?’

‘I can guess. What else?’

‘A brown tweed costume. A chartreuse blouse, green shoes, nylons, fur coat, hat, purse, and gloves.’ She rattled off the list as though she had learned it by heart. I looked up from my notebook.

‘What kind of fur coat?’

‘Silver fox, three-quarter length.’

‘What colour hat and gloves?’

‘Black, I think.’

‘Don’t think, be sure. What colour?’

‘Black.’ This time she was certain, and I knew that I wouldn’t get a different answer no matter how hard I tried. ‘Jewellery?’

‘A stack of it. Wristwatch, gold and studded with diamonds. Two bracelets, one of rubies and diamonds, the other emeralds. Four sets of earrings, a couple of ropes of pearls, some dress clips, and a hatful of rings.’

‘A lot of jewellery.’

‘Most of what she had.’ Marie sounded vicious, and I wondered why. ‘She cleaned out the jewellery box but good. Now, I suppose, some gumshoe will accuse me of helping myself.’

‘Why should they?’

‘I know coppers.’ Marie dragged at her cigarette. ‘Anything else?’

‘Did she take any suitcases?’

‘No.’

‘Then she must have shoved the jewellery in her pockets or purse?’

‘I guess she must have done.’ Marie shrugged. ‘She was always a crazy dame; I guess she just got fed up with the old man and took a powder with all the portable loot.’

‘What make you say that? Did they fight?’

‘Not so’s you’d notice,’ she admitted. ‘But she was always chasing off and leaving him to worry about her. If you ask me, he began to regret having married a tramp.’

‘She was in the habit of taking off, was she?’ I crushed out my cigarette and slipped the notebook back into my pocket. ‘Any idea where she went to?’

‘No.’

‘Did she ever talk to you about her friends?’

‘No.’

‘Not much help, are you, Marie?’

‘No.’

‘I see.’ I took out another cigarette and poised it in front of my mouth. ‘Why do you think she’s dead, Marie?’

‘Dead!’ Now she looked scared for the first time. ‘I didn’t say that.’

‘Yes, you did. Not right out, maybe, but in other ways. Why else would you be afraid of someone thinking that maybe you’ve helped yourself to the jewellery? If she was still alive, the question would never arise.’ I dropped the cigarette and gripped her shoulders. ‘Come on, Marie, give! What do you know?’

‘Nothing!’ She wriggled and I held on. ‘I don’t know nothing, I tell you.’

‘Is she dead?’

‘I don’t know!’ She was getting frantic by now. ‘Honest to God, shamus, I don’t know!’

I believed her. I let her go and she rubbed the places where my fingers had dug. Her eyes told me she hated me, but they told me more than that. Marie was scared, plenty scared, and I wondered why.

I was still wondering when she ran out of the room and slammed the door behind her.