Читать книгу Mistress of Mistresses - E. Eddison R. - Страница 7

FOREWORD BY DOUGLAS E. WINTER

Оглавление‘Is this the dream? or was that?’

WORDS create worlds: storytelling is a kind of godhood, taking the imperfect day of language, moulding it in the writer’s own image and, with skill, breathing it to life. The task is a formidable one, and it is little wonder that most fiction is content with reinventing reality, safely sculpting what is known. And why not? Stories are for the most part entertainment, ephemeral, meant only for the moment. Few novels strive for life beyond their covers; few hold us in their dominion for years, fewer still for lifetimes. The words and the worlds of E. R. Eddison, which I first discovered more than twenty years ago, still intrigue me, uplift me, haunt me, today. I know that I am not alone.

Eric Rücker Eddison (1882–1945) was a civil servant at the British Board of Trade, sometime Icelandic scholar, devotee of Homer and Sappho, and mountaineer. Although by all accounts a bowler-hatted and proper English gentleman, Eddison was an unmitigated dreamer who, in occasional spare hours over some thirty years, put his dreams to paper. In 1922, just before his fortieth birthday, a small collector’s edition of The Worm Ouroboros was published; larger printings soon followed in both England and America, and a legend of sorts was born. The book was a dark and blood-red jewel of wonder, equal parts spectacle and fantasia, labyrinthine in its intrigue, outlandish in its violence. It was also Eddison’s first novel.

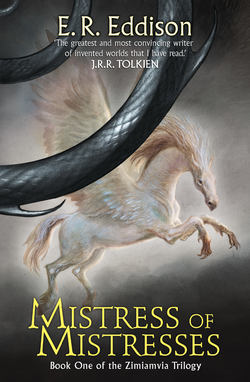

After writing an adventure set in the Viking age, Styrbiorn the Strong (1926), and a translation of Egil’s Saga (1930), Eddison devoted the remainder of his life to the fantastique in a series of novels set, for the most part, in Zimiamvia, the fabled paradise of The Worm Ouroboros. The Zimiamvian books were, in Eddison’s words, ‘written backwards’, and thus published in reverse chronological order of events: Mistress of Mistresses (1935), A Fish Dinner in Memison (1941), and The Mezentian Gate (1958). (The final book was incomplete when Eddison died, but his notes were so thorough that his brother, Colin Eddison, and his friend George R. Hamilton were able to assemble the book for publication.) Although the books are known today as a trilogy, Eddison wrote them as an open-ended series; they may be read and enjoyed alone or in any sequence. Each is a metaphysical adventure, an intricate Chinese puzzle box whose twists and turns reveal ever-encircling vistas of delight and dread.

Eddison’s four great fantasies are linked by the enigmatic character of Edward Lessingham – country gentleman, soldier, statesman, artist, writer, and lover, among other talents – and his Munchausen-like adventures in space … and time. Although he disappears after the early pages of The Worm Ouroboros, Lessingham is central to the books that follow. ‘God knows,’ he tells us, ‘I have dreamed and waked and dreamed till I know not well which is dream and which is true.’ One of the pleasures of reading Eddison is that we, too, are never certain. Perhaps Lessingham is a man of our world; perhaps he is a god; perhaps he is only a dream … or a dream within a dream. And perhaps, just perhaps, he is all of these things, and more.

In a transcendent moment of The Worm Ouroboros, the Demonlords Juss and Brandoch Daha, searching desperately for their lost comrade-in-arms, Goldry Bluzco, ascend to the dizzying heights of Koshtra Pivrarcha. There, in the distance, they see paradise. Lord Juss speaks:

‘Thou and I, first of the children of men, now behold with living eyes the fabled land of Zimiamvia. Is that true, thinkest thou, which philosophers tell of that fortunate land: that no mortal foot may tread it, but the blessed souls do inhabit it of the dead that be departed, even they that were great upon earth and did great deeds when they were living, that scorned not earth and the delights and the glories thereof, and yet did justly and were not dastards nor yet oppressors?’

‘Who knoweth?’ answers Brandoch Daha. ‘Who shall say he knoweth?’

If anyone knows, it is Edward Lessingham. In the Overture to Mistress of Mistresses, we learn that old age has claimed him, his final hours watched over by a mysterious lover. Lord Juss’s question is repeated, and the reader – like Lessingham – is taken straightaway to Zimiamvia. This is neither the biblical paradise, nor that of classical mythology, but a mad poet’s dream of Northern Europe during the Renaissance. Zimiamvia is an imperfect heaven – what other kind could exist without boredom for its residents? – a Machiavellian playground for men and gods, where mystery and menace, romance and revenge, swordplay and soldiering are the natural order of things.

Three kingdoms comprise this otherworld – known, from north to south, as Fingiswold, Rerek and Meszria – and all are ruled by the wise, firm hand of King Mezentius. In Zimiamvia, Lessingham lives on, his earthly self a duality. His namesake, Lord of Rerek, is his Apollonian half – the embodiment of reason, logic, science. Lord Lessingham is cut from the same cloth as the Demon heroes of The Worm Ouroboros, a demigod and bravo, a man of action and of honour with but a single stain: kinship, and thus loyalty in blood, to Horius Parry, the ambitious Vicar in Rerek. Parry, in turn, is the scheming serpent of this enigmatic Eden, a villain extraordinaire whose instinct for treachery and terror – and for surviving to scheme again another day – is worthy of the most diabolical of devils.

Lessingham’s Dionysian qualities – magic, art, and madness – are found in Duke Barganax, bastard son of King Mezentius and his mistress Amalie, the Duchess of Memison. Barganax takes counsel in the aged yet ageless Doctor Vandermast, a mysterious Merlin who is given to spouting Spinoza and minding his lovely shapeshifting nymphs, Anthea and Campaspe. ‘My study,’ says Vandermast [in A Fish Dinner in Memison], ‘is now of the darkness rather which is hid in the secret heart of man: my office but only to understand, and to watch, and to wait.’

With the deaths of King Mezentius and his only legitimate son, Styllis – in which Parry’s perpetually bloody hand is suspect – the crown descends to the beautiful and doomed Queen Antiope, with whom, inevitably, Lord Lessingham will fall in love. The struggle for power, by wile and war and witchery, enwraps Zimiamvia in a web of passion and violence that is tangled by strange shifts of time.

‘Time,’ Eddison tells us, ‘is a curious business’, and in Zimiamvia it grows more and more curious. ‘Is this the dream?’ his characters ask, ‘or was that?’ [A Fish Dinner in Memison]. These tales are not simply written backwards, they defy most novelistic notions of time. Eddison was exceptional in his embrace of the fantastique; in his fiction there are no logical imperatives, no concessions to cause and effect, only the elegant truths of the higher calling of myth. Characters traverse distances and decades in the blink of an eye; worlds take shape, spawn life, evolve through billions of years and are destroyed, all during a dinner of fish. These are dreams made flesh by a dreamer extraordinaire.

Ten years: ten million years: ten minutes. One and the same, says Eddison, and in Zimiamvia we journey beyond the pure heroic adventure of The Worm Ouroboros into an existential-romantic quest, a speculation on the nature of woman and man, Goddess and God, reality and dream: ‘It was in that moment as if he looked through layer upon layer of dream, as though veil behind veil: the thinnest veil, natural present: the next, as if a dumb-show strangely presented by art magic’ [Mistress of Mistresses]. Eddison’s characters exist beyond time, beyond dimension, woven into a tapestry that circles and circles on itself, as abiding and eternal as its central image: the worm Ouroboros, that eateth its own tail.

‘If we were Gods, able to make worlds and unmake ’em as we list, what world would we have?’ [A Fish Dinner in Memison]. Here is the central dilemma of Zimiamvia: the nature and means of creation. Worlds within worlds, stories within stories, characters within characters, phantasms within phantasms – this is a majestic maze of mythmaking, a fiction that questions all assumptions of reality. Eddison thus proves more than a dreamer; like the very best writers of the fantastique, he saw this fiction of (im)possibilities as the truest mirror of our lives, one that shines back brightly the depths of the human spirit as well as the surfaces of the flesh.

Eddison’s prose is archaic and often difficult, an intentionally affected throwback to Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. His characters are thus eloquent but long-winded; they speak not of killing a man, but of ‘sending him from the shade into the house of darkness’ [The Worm Ouroboros]. In his finest moments, Eddison ascends to a sustained poetic beauty; listen, for example, to the haunting premonition of the renegade Goblin Gro:

‘For as I lay sleeping betwixt the strokes of night, a dream of the night stood by my bed and beheld me with a glance so fell that I was all adrad and quaking with fear. And it seemed to me that the dream smote the roof above my bed, and the roof opened and disclosed the outer dark, and in the dark travelled a bearded star, and the night was quick with fiery signs. And blood was on the roof, and great gouts of blood on the walls and on the cornice of my bed. And the dream screeched like the screech-owl, and cried, Witchland from thy hand, O King!’ [The Worm Ouroboros]

At other times the reader is virtually overwhelmed with words. Palaces and armoury were Eddison’s particular vices; he describes them with such ornate grandeur that page after page is lavished with their decoration. The reader should not be deterred by the density of such passages; like a vintage wine, a taste for Eddison’s prose is expensively acquired, demanding the reader’s patience and perseverance – and it is worthy of its price. These are books to be savoured, best read in the long dark hours of night, when the wind is against the windows and the shadows begin to walk – books not meant for the moment, but for forever.

The Zimiamvian trilogy inevitably has been compared with J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, but apart from their narrative ambition and epic sweep, the books share little in common. (Eddison, like Tolkien, disclaimed the notion that he was writing something beyond mere story: ‘It is neither allegory nor fable but a Story to be read for its own sake’ [The Worm Ouroboros’ preface]. But as the reader will no doubt observe, he proves much less convincing.)

If comparisons are in order, then I suggest Eddison’s obvious influences – Homer and the Icelandic sagas – and that most controversial of Jacobean dramatists, John Webster, whose blood-spattered tales of violence and chaos (from which Eddison’s characters quote freely) saw him chastised for subverting orthodox society and religion. The shadow of Eddison may be seen, in turn, not only in the modern fiction of heroic fantasy, but also in the writings of his truest descendants, such dreamers of the dark fantastique as Stephen King (whose own epics, The Stand and The Dark Tower, read like paeans to Eddison) and Clive Barker (whose The Great and Secret Show called its chaotic forces the Iad Ouroboros).

Eddison would have found this line of succession, like the cyclical popularity of his books, the most natural order of events: the circle, ever turning – like the worm Ouroboros, that eateth its own tail – the symbol of eternity, where ‘the end is ever at the beginning and the beginning at the end for ever more’.

Welcome to that fabled paradise, Zimiamvia: Once you have entered these words, this world, you may never leave.

DOUGLAS E. WINTER

1991

in memory of Phil Grossfield