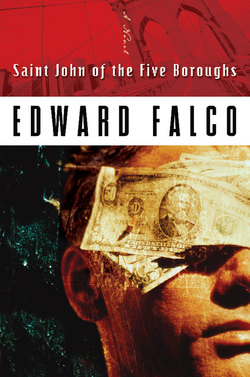

Читать книгу Saint John of the Five Boroughs - Ed Falco - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA watery rumbling in Avery’s belly woke her, and when she sat up in bed the headache she had been dully aware of in her restless sleep expanded suddenly, as if unseen hands had yanked a too-small hat down over the back of her head. She gritted her teeth against the pain and lay back down, keeping as still as possible while she waited for the throbbing to stop. She had been dreaming about a lake . . . and a boat . . . a dark lake, a small boat. Her father was on the shore. She was in the boat. It was night and the lake was still, a dark glassy surface, and the boat was floating away, but . . . a strand of her hair connected her to the shore. Her father was holding the other end of the strand, and she was leaning toward him . . . then the hair snapped and she watched it dent the water’s surface in a long straight line to the shore where her father was a shadow that grew smaller as the boat kept drifting away.

When the throbbing finally let up and Avery opened her eyes again, the memory of the dream settled over her like a heavy blanket. Her father had died the summer after her high school graduation, suddenly, of a cerebral aneurism, in his sleep. She dreamed of him regularly, and often the dreams were comforting. He’d hug her, or give her a kiss on the forehead the way he used to. But sometimes the dreams were like this one, and she’d wake up feeling heavy and slow, as if the air around her were so dense she could barely move.

Zach rolled over and put his hand on Avery’s knee, and she looked down at him as if she were annoyed at discovering someone else in her bed. He asked if she was okay in a voice that sounded impossibly gentle given the hulking mass of body out of which it issued. She told him to go back to sleep, which he did instantly, closing his eyes and snuggling his forehead against her thigh. She was fully awake then, lying in bed next to a football player she had met only a few hours earlier—and as the events of the night came rolling back through her sober memory, she groaned and checked the alarm on her night table. It was a little after three in the morning. She had been in school all of one full week, this her senior year. Her room was dark, but there was enough light from her various electronic devices to see the mess of clothes scattered over the floor and the disorderly array of cosmetics covering the top of her dresser. In the pulsing white light of her sleeping iBook, the rose-colored walls lightened and darkened as if breathing peacefully. On the wall opposite her bed, the muted greens in a poster-sized photograph of the Folly Beach pier echoed the steady green light of her recharging cell phone. She had bought the framed picture for ten dollars at a yard sale in Salem, where an elderly man had held it up and pitched the value of the frame—but she had bought it for the picture, which captured the elaborate crisscross of mossy pilings beneath the pier as they narrowed in diminishing perspective to a flash of bright light where the pier ended and frothy ocean waves surged. That flash of white light in the distance looked to Avery like a cathedral door, like an opening into another, utterly different world.

In this world, her head was still aching. Gingerly she slid out of bed and into the first things she found at her feet, which were a frayed pair of denim cutoffs and an ancient band T. She paused a moment at her bedroom door when she thought she heard a sound coming from Melanie’s room. She pressed her ear to the wall beside her dresser and listened, and when she didn’t hear anything more, she went quietly along the hall to the bathroom, where she washed down three aspirin in a palmful of water and then chewed four Tums on her way back to her bed. The living room was a disaster. The couch was overturned where Zach had tripped over it, and there was a stain on the carpeting where the wine bottle he had just opened had spilled as he’d fallen on his face. Drunk as he was, he wasn’t drunk enough not to be embarrassed. He kept promising to clean it in the morning or to pay the damage deposit until Avery finally shut him up by taking him by the hand and pulling him into her bedroom. What she remembered most vividly, though, was the way Grant, Melanie’s shaved-headed pickup for the night, had calmly watched Zach from where he leaned back soberly into the window frame, and then the way his eyes met hers just as she was closing the bedroom door.

While she was gone, Zach had stretched out like a skydiver, his spread-eagled arms and legs reaching to the four corners of the mattress. His body was freakish, and Avery observed him for a long moment with fascination. From head to toe, he was everywhere twice as thick as most other guys. His calves had the girth of telephone poles, and they widened proportionally to massive thighs, a back broad as a coffee table, an impossibly thick neck, and an almost square head with fleecy dark hair. It seemed impossible that she had actually just had sex with this guy. It looked like the weight of him alone would crush her.

She went to the window and looked out over a narrow strip of moonlit lawn that ended at a line of tall trees, beyond which was the highway, and while she was at the window, a doe wandered halfway through the tree line, looked about for a few seconds, and then bounded away through the trees and out onto the quiet highway. Avery went back to her bed, sat on the edge of the mattress, and shook Zach’s arm. “Zach,” she said, and he opened his eyes instantly.

“Hey—” He blinked a few times and looked as though he were working to pull himself back fully into consciousness. “What? Are you okay?” He propped his head up on his elbow and then, as if to announce he was now awake, smiled sweetly.

“Sure,” Avery said. “I’m fine. But, look, you have to go.”

“Really,” he said. “You want me to leave?”

“It’s just, you know—” She made a face, as if she expected him to understand, naturally, why it was obvious he should leave.

“What?” he said. “Was I snoring?”

“Loud,” she said. “Really, I’m sorry. I’m not used to it.”

“Oh . . .” He grimaced. “I do that.” He thought about it for another second and then added, “I could try to stop.”

Avery brushed a long strand of hair back off his forehead. “You’ve been sweet,” she said. “You’re not at all like you seemed at the party.”

“I’m not?” he said. “How did I seem? At the party.”

“Yo! Missy!” Avery mocked his voice.

Zach laughed. “That’s just—” he said. “I’m not like that. I’ve got to drink to put on that whole thing.”

“Why?” Avery folded her hands in her lap and looked at him like a schoolteacher working with a student. “Why do you have to put on that whole thing?”

“Otherwise I never meet anyone,” he said. “The guys make fun of me. They’re all like—” He looked away for a moment, up over Avery’s head. “They make fun of me is all.” He laughed, as if amused at himself. “I realized, you know, I’ve got to act a certain way or else they make my life miserable.”

“You have to step in front of girls and go, Yo! Missy!” She did his voice again, which made him laugh again.

“Exactly.” He leaned close and kissed Avery’s thigh through the shreds of denim fringe. “You sure I have to go?”

“I need to get some sleep,” she said, “and I’m not used to anybody else in my bed.”

“That’s good,” he said. “That’s encouraging.”

“Really? Why?”

Zach watched Avery as if he were trying to say something to her with his eyes and a slight, mischievous, smile. Then he spun around and out of bed and stood naked in front of her.

“You’re full of yourself, aren’t you?” she said.

“Me?” He sounded as if he had no idea what she was talking about, even though the grin on his face said he did. “Why?”

“ ‘Why?’ Are you modeling for me?”

“Oh.” Zach looked down at himself. “You think I could be a model?”

Avery said, “I think you should get dressed.” While Zach was getting into his clothes, she cocked her head at what she thought was the sound of the refrigerator door opening.

Zach apparently didn’t hear anything. He said, “Want to see me out?”

“Sure.” She slid off the bed and gave him a hug. “You’re sweet,” she said again and led him out into the living room, where she was startled by the reflection in the sliding glass doors to the balcony. She saw herself a step in front of Zach as he loomed hugely behind her, her head reaching up only to his shoulders, her body dwarfed by his bulk. With her braless, in fringed jeans and snug T, and Zach in tight denims and short sleeves that threatened to rip at his biceps, they looked like a couple of characters out of the Dukes of Hazzard. In the background of the reflection, Grant stood at the refrigerator with a bowl of ice cream in one hand and a spoon in the other. He nodded at Zach and Avery before he lifted the spoon to his mouth. The couch had been turned upright, and a wet towel lay over the wine stain on the carpet. “Shit,” Zach said, looking down at the towel. “I forgot about the wine.”

Grant nodded toward the towel and said, “I thought that might help.” Then he shrugged as if he actually had no idea whether or not it would do any good.

Avery liked the sound of his voice. She asked another question mostly just to hear him speak again. “You know something about cleaning up spilled wine?”

Grant smiled enigmatically and then took a seat on the couch, turned on the television, and started flipping through channels.

Avery gave Zach a look, and he hesitated at the door, as if to ask if she were wary of Grant. She leaned against him and stood on her toes to kiss him on the cheek. “Good night, Zach,” she said.

“Can I call you tomorrow?”

“I made plans with my family for tomorrow. Call me during the week.”

Zach nodded, the disappointment on his face obvious. Before he left, he glanced over to Grant on the couch, where he had settled in before a black-and-white movie.

Once Zach was gone, Avery locked the door and leaned back against it. The movie on the television was Casablanca. She had seen it ten times, at least. It was coming up on the scene where the Nazis are in the club and Rick has the band play “La Marseillaise.” “I love this scene,” she said and sat on the other end of the couch.

Grant’s eyes were fixed on the television as he held the bowl of ice cream in his lap. Avery was tempted to ask how old he was. She also wondered why he was out here and not with Melanie. He was, she decided again, handsome—in an interesting way. His lips were pink and shapely and full—the kind of lips women hope for when they get collagen injections—but the top of his nose was flat and wide, the broad lines merging with thick eyebrows that looked like a pair of wings over intense dark eyes. His ears were smallish and pressed back almost flat against his head. The overall effect, emphasized by the military haircut, was brutal, warrior-like, at least at first glance, though the lips undercut the harshness and suggested other possibilities.

“I think,” she said, referring to the “Marseillaise” scene, which had just ended, “it’s, like, the hopelessness of the gesture, standing up to the Nazis, that’s so moving.” She surprised herself with her sudden talkativeness. She seemed, out of nowhere, full of questions and observations.

Grant muted the sound on the television and then settled back on the couch facing her. “It’s the defiance,” he said.

Avery said, “I think it’s stirring.” When Grant didn’t keep up the conversation, she added, “Don’t you think?”

Grant watched her long enough to make Avery uncomfortable. Finally he said, “I think there’s something special about you.”

Before the words were fully out of his mouth, Avery half laughed, half snorted—a dismissive response that happened without thought, mostly out of surprise. “Did you tell Melanie that tonight, that there was something special about her?”

“No,” he said. “Did you tell Zach he was special?”

Avery considered getting up and going back to her room. Instead she said, “I’m just trying to be friendly.”

“Really?” Grant turned back to the television and clicked on the sound. In a moment, he seemed absorbed again in the movie.

“Dude,” she said, “you’re majorly fucked up.”

Grant didn’t look at her but laughed quietly. “Dude,” he said, under his breath. “Majorly,” he added.

Avery got up slowly, hoping the right rebuke would come to her, and when it didn’t she had to settle for a contemptuous snort that came off as theatrical even to her. She went back to her room, closed the door quietly behind her, and sat on the edge of her bed in the dark. Part of her wanted to slip under the covers and go to sleep. Part of her wanted to go back out to the living room and tell Grant to get the hell out of her apartment. Dude. Majorly. Jesus, what was she, fifteen all of a sudden? She heard him again, mocking her under his breath, contemptuous—and she had to swallow and her fists clenched into little rocks. The room approached and retreated in the throbbing light from her iBook, rose walls appearing and fading. The dresser top cluttered with makeup and jewelry, the Folly Beach pier, a framed Picasso print, a framed Dali: here and gone, here and gone. She should just march into the living room and ask him who the hell he thought he was, hitting on her after just having slept with her girlfriend, knowing she had just slept with Zach. What kind of freak was that? How was she supposed to react?

Unless he wasn’t hitting on her . . . though of course he was. I think there’s something special about you. What else was that?

In her quiet bedroom, Avery paid attention to the palpitating of her heart, the quick shallow breathing, the tingling of her scalp that signaled the approach of a panic attack. She hadn’t had one in almost a year. She had stopped taking her Zoloft at the end of the spring semester. But here it was, coming on, and now she was almost as furious as she was scared. Scared of the fear approaching, the way it cramped her heart and overwhelmed her so that she couldn’t breathe, but furious at the same time. Why should something like this bother her, why now? Though it wasn’t just this, it was the dream too, the dream of her father and the lake, and the weight that had settled over her afterward, the heaviness of being alone, unmoored.

She got up and turned on a light. With the back of her hand she swiped away the sweat on her forehead. On her desk, a thick art book, Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces, was propped up against her computer. She flipped through the pages until she came upon a quote from Gerhard Richter, Art is the highest form of hope, beneath a painting that looked like a blurred photograph of a young woman holding a hand over her mouth, looking either terrified or bored, all her edges jittery, as if she might be coming apart. She continued turning pages until she came to an oil titled Monk by the Sea, which was what she had been looking for—though not that specific painting, just something calming, peaceful, beautiful, which was a technique she had learned back when the panic attacks were frequent and bad: immersing herself in the right kind of image, forcing herself into it, pushed her out of herself. And it helped, this particular painting a gorgeous play of blues: light blue sky, inky blue water, icy blue land, and a lone figure in the midst of the vast blue expanse, but somehow not overwhelmed, solitary, not lonely. She imagined that she was the figure in the painting, which was not hard, and after a while her heart stopped palpitating and her breathing returned to normal. She bookmarked the page and turned off the light and then knelt in front of her window.

I think there’s something special about you. She had reacted viscerally—as if he had called her a whore, as if she would get out of bed with one guy and into bed with another. Though, now, kneeling at the window, looking out at nothing, she considered the possibility that it was all in her head, that he might have meant nothing like that at all; that she was, on a not very deep level, ashamed of herself for going to bed with a guy who meant nothing to her, who, if anything, amused her. She wondered if her reaction to Grant’s words weren’t more about her own unhappiness with herself and the uneasiness of her mood than anything he had actually said. I think there’s something special about you.

She went from the window to her bed, where she stripped out of her clothes and pulled the sheet to her neck. She lay on her back, her head propped up on two pillows. From the kitchen, she heard the refrigerator open and close, then the clank of a dish in the sink, and then, Jesus, she tightened up at the prospect of listening to him go back to Melanie’s room. She could feel it in her shoulders and her neck, the clenching against the unpleasantness of it, listening to him as he opened and closed the door and got back into bed with Melanie—and when he didn’t, she was relieved. She got up and looked herself over in the full-length mirror beside her dresser.

There she was, staring back at herself, the whole of her reflected in the mirror—and it was as if she could see only her thighs. She grasped the extra handful of flesh in her fist and then quickly let go, a little angry gesture without thought. She laid one hand flat over her stomach, over the pouch of belly that she never saw on one model in the whole world of television and magazines and movies, but most of her friends and most of the girls at the pool and the gym had at least a little belly, a little looseness or jelly there—and the older women, Jesus, clearly there came a point when all of them gave up the battle. But her thighs—they weren’t that bad, not really. Her legs were fine. Her breasts were nice. Lots of guys thought she was pretty. She might have to diet a bit. Just a little. She thought she sort of looked like Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction. A little anyway. She had the dark hair and the straight bangs, and the way her hair fell on the sides, lustrous and straight, to her chin, framed her face in three neat sides of a rectangle, which was the Uma Thurman/Pulp Fiction part. She had pretty eyes, a little bigger and rounder than most. Her eyes were dark and with the dark hair, she liked that too. She decided not to turn around and check out her ass, and then she did anyway. And there it was. Her ass. It was okay. She pulled on the same shorts and T-shirt, so he wouldn’t think she had changed for him, straightened out her hair, and then went out to the living room.

Grant was on his back, apparently doing leg lifts. He lay stretched out parallel to the television set, his hands clasped around the back of his neck, heels six inches off the floor. The way he was holding his feet up with legs out straight tensed the muscles of his stomach, the broad chest and magazine-ad abs clearly defined under the cotton of his T. With great effort, Avery could hold that position—legs out straight, heels six inches off the ground—for about two seconds. Grant seemed to hardly notice it. He had turned his eyes to Avery as soon as she had entered the room, and he watched her now as she took a seat on the couch, folding her legs under her.

“All I meant,” he said, “is that there’s something about you that’s intense. It’s like an aura around you.”

Avery gave him her most skeptical look, one she hoped would encourage him to drop the subject.

“So,” he said and then fell quiet and stared at her unabashedly, his eyes roaming over her face and then meeting her eyes and staring into them with a disorienting objectivity, as if he were examining them, as if he were a physician looking for signs or symptoms. “So tell me,” he said finally. “I’m a good listener. I feel like we could connect.”

“Tell you what?” Avery looked at him as if he were a little crazy. “What do you mean, connect? What does that—”

With a small shake of his head, Grant dismissed her questions. “You’re the one I noticed at the party,” he said. “It was you I was staring at, not Melanie.”

“You were staring at me?” Avery heard herself raising her voice and was immediately frustrated. “Why would you be staring at me?”

“Why wouldn’t I be staring at you?”

Avery laughed. She could hardly believe . . .“Why are you coming on to me like this?” she said, her voice suddenly quieter. “You just got out of bed with my girlfriend.”

“What makes you think I’m coming on to you?”

“Are you serious? Why wouldn’t I be staring at you?” She mimicked his suggestive tone.

The refrigerator clicked on loudly and rumbled for a second before settling into its white-noise hum. “All I’m saying,” Grant said, “there was something happening with you, something special about you. Even through the drinking, it was there. I could see it.”

“What was there?” Avery shrugged as if she had no idea what he was talking about. “I don’t have a clue.”

“Yes, you do,” he said, and then he appeared to suddenly turn off, as if a switch had been thrown in some internal circuitry. His face turned hard and impassive, and he went back to looking at the ceiling.

Avery watched him. His feet were still floating effortlessly six inches off the floor. His eyes were fixed on a spot directly above him, though he obviously wasn’t seeing a thing. He was so inside himself it was as if he had disappeared. “Can we try again?” she said. “I’m Avery. I’m a student here, in the Art Department. What about you? I don’t know a thing about you. You could be . . . anybody.”

He said, “I’m here spending a couple of weeks with a friend.” He turned to look at her. “He used to be a street performer. Now he’s a professor. It’s like—The guy wears a jacket to class.” He seemed amazed at the unlikeliness of it. “It’s—Man. Who are you?”

“What do you mean, street performer?”

“The thing that got him famous—” Grant let his feet drop. He turned on his side and propped his head on one hand.

“How long could you have done that?” Avery asked. “Keep your legs lifted like that.”

“Forever,” he said, uninterested, and then went back to the subject of his friend. “One of the things that got him famous, anyway. He stabbed himself in front of the Met. A Sunday afternoon in spring. Beautiful weather. French Impressionists show. Tourists? Coming out your ears.”

“He literally stabbed himself?”

“Once in the chest, once in the stomach. Screaming some shit or other about art.”

“And he teaches here?”

Grant nodded.

“So. But. That was it? He stabbed himself? That makes him an artist?”

Grant looked away, as if momentarily annoyed. “He’s a performance artist,” he said. “He’s in the Theater Department.” When he looked back at her, he said, “Do you want to go for a ride?”

“Now?” Avery leaned forward, partly taken aback and partly, to her own surprise, excited. “It’s four in the morning.”

“We could watch the sunrise. There’s a lake not that far from here.” He sounded as though he were merely putting a proposal on the table, as if he were curious whether she would take him up on his offer.

“So, what?” Avery said. “You’re a professor too? You were teaching here?”

“Just visiting,” he said. “Are we going?”

Avery looked over her shoulder at Melanie’s closed bedroom door. As if Melanie sensed her attention, a small sleep sound issued from the room, a soft groan and a rustling of sheets. Avery waited, and when the sound was followed only by silence, she turned back to Grant. “You know,” she whispered, “if Melanie finds out that I went for a ride with you at four in the morning . . .”

“I’ll have ruined your reputation,” Grant said.

“I’ll have to find another place to live is what I was thinking.” Avery got up, about to go back to her room to change. “I have no idea why I’m doing this.” She hoped her expression conveyed at least a little of her genuine amazement.

Grant said, “Wear something warm and put on a jacket. I ride a bike.”

Avery said, mostly to herself, “Should have figured . . .”

Once she closed the door to her room, Avery turned off the lights, as if she needed the help of darkness to think. In the softest of whispers, but aloud, she said, “What are you doing, Avery?” and she pulled off her T-shirt and sent it sailing over the bed. No answer came immediately to mind, but a small voice out of some corner of herself urged her to change her mind, to go back out into the living room and tell him she was just too tired, or, even better, to just go to bed and leave him waiting; and as that quiet voice spoke to her, she got out of the rest of her clothes and then turned on the lights and rummaged through her dresser. While she was putting on her jeans and finding a clean blouse and then searching through the closet for her best buttery black leather jacket, she continued to entertain the possibility of not doing it, of not taking a four A.M. motorcycle ride with a guy who’d just gotten out of bed with her best friend after she’d just gotten out of bed with another guy. It was too crazy. She couldn’t do it; and then, a few minutes, later, she was dressed and out on the streets of State College with Grant, heading for town.

His motorcycle was parked in a lot behind the Days Inn. A sleek machine that looked as much like a missile as a bike, its compact black body soaked up light, a kind of shadow tilted cockily to one side. Grant had her wait while he went up to his room and returned with a pair of black helmets with black Plexiglas face masks, and a moment later they were riding into the night, slowly at first through town, then flying over lonely state routes faster by far than she had ever experienced before, trees and road rushing by in a dark blur, her arms wrapped around Grant’s waist, her head pressed into his back to block the wind. When what seemed to be a half hour or more had passed and they were still speeding over unfamiliar roads, farther and farther from civilization, she felt the first creeping traces of uneasiness working their way through her, and, later, as the ride went on and on, part of her turned unambiguously frightened—though another part of her, perhaps the bigger part, was thrilled. The dark flew by all around as she held tightly to Grant, her arms around his waist, her body against his. She leaned into the turns with him, hurtling over the road only a few feet off the ground, nothing to protect her but him, his solid body piloting a sleek shadow through shadows.

When they came to a stop, eventually, on the wooded shore of Raystown Lake, it was still dark, but morning and sunrise couldn’t be far away. She climbed off the bike and pulled off her helmet, and then they both moved toward a fallen tree at the edge of the water. The lake was glassy and quiet, dark and unmoving as a sheet of black plastic. She sat on the log and looked at the opposite shore, where trees crowded a hillside and descended to water. The early-morning air was crisp against her skin, and it smelled of pine and something else she couldn’t name, something rank that seemed to rise up from the water’s edge. The earth at her feet was covered with an inch-deep layer of moss that extended halfway to the lake like a blanket, and on a whim she pulled off her boots and socks and pressed her toes into the cool moist ground. She heard the crack of a breaking branch, and then Grant stepped over the log and sat beside her holding a small tree limb in his hands like a fishing pole—and at the sight of the fishing pole/tree limb, her dream came back to her and her head snapped back to the lake as if she might see herself floating away from the shore in a small boat, a strand of her hair stretching across the water.

Grant said, “Did you hear something?”

She shook her head, dismissing him, and continued staring out over the water, where again she saw the lake from her dream—the strand of hair her father was holding connecting her to him and to the shore, and then the strand snapping and then her drifting away. While she stared out over the black water of the lake, the dream’s images shifted into a flurry of memory and feeling, and a breeze slid over the water and through the underbrush along the shore. It was like something coming at her, this breeze she could see in the ripples on the lake and the fluttering of leaves and then feel against her skin and it seemed to carry with it a moment when she was a child and her father was holding her in his arms and pointing up at the moon and telling her he loved her, that he’d always love her, under that fat white moon, the same fat white moon floating now somewhere out of sight.

Beside her Grant sat quietly in a tongue of moonlight watching her. After a while, after a long silence, she told him about her father and about the dream, how strange it made her feel to wake up from a dream about a lake and then find herself sitting on the shore of just such a lake only a few hours later.

Grant said, “What do you believe?”

Avery slid away from him. “What do you mean?”

“I’m asking what you believe. Spiritually.”

“Spiritually,” she said, working to grasp the question. She looked into the woods, as if the answer might be waiting for her there. She tried to think about the question seriously, but nothing came to her. She said, “My family is Episcopalian,” though she knew that was no answer. “I don’t know. We never really talked much about that stuff growing up. We never went to services or any of that either, so . . . I guess I don’t know what I believe.” She folded her hands in her lap and looked at Grant. “Why?” she said. “What do you believe? Spiritually?”

“I don’t know either,” he said, “but I can’t believe it’s a coincidence you’d dream about a lake exactly like this lake and then find yourself here.”

“Then what?” she asked. “If it’s not a coincidence?”

Grant bent over and undid his laces, and he seemed to be thinking in the process. “Then it’s a mystery,” he said, and he kicked off his shoes.

“What are you doing?” Avery leaned back and stretched.

Grant undid the buckle and zipper of his chinos and pulled them off. Beneath them he was wearing a pair of white briefs. “I have an urge to get in the water.”

“You’re shy,” she said.

He looked down at his briefs. “More modest than some bathing suits.”

“I suppose.” Her thoughts flashed back to Zach a few hours earlier, showing himself off in front of her.

Grant went down to the water and stepped in, gingerly at first. “Huh,” he said, “the water’s warmer than the air.” He walked in all the way up to his waist and looked toward the wooded tree line across the lake. “It’s beautiful out here.” He took off his shirt, threw it to the shore, and dove into the water.

Avery thought he was beautiful. Unlike Zach’s freakishly huge body, Grant’s was sleek and compact and beautifully muscled. Michelangelo’s David came to mind, the gracefulness of the musculature, Grant’s skin looking as hard and flawless as the statue’s marble. While she watched, he surfaced, took a deep breath, arched his body, and dove again, this time going deeper, she could tell by the breath he took and the way he dove. She went to the edge of the water, her bare toes sinking down into mossy silt. The surface had closed over Grant’s dive, and the lake looked unchanged, peaceful and dark. If she hadn’t seen him disappear, there’d be no way to know anyone was in the water. When he came up again, he was only a few feet away from her. He exploded out of the lake, shaking off water, and the spray caught her in the face and chest. She jumped back, startled, and then laughed.

Grant took a moment to catch his breath. “It’s like being in a deprivation chamber down there,” he said. “You can’t see or hear anything and the water’s so warm—”

Avery picked up his shirt, which was caught on a bush beside her. She wiped her face with it. “You got me wet.”

“What I was thinking, down there,” he said, “is that it feels like you and I are supposed to be here. I mean,” he said, “the way I felt when I saw you. Your dream. Some things, they feel—” He looked at the sky and placed one hand flat over his heart, as if he were about to pledge something. “They feel as if somehow they had already happened.” He looked back to Avery, his hand sliding down to his belly.

“Is that what you were thinking,” Avery said, “that we were destined to meet?” She had a slight, wry smile on her face, and she meant to sound at least a little dismissive, but she wasn’t sure it had come out that way.

“There are people who believe,” he said, “that we’re all spirits, and that the ones you connect with in this life, the ones you love or have deep friendships with, they’re from previous lives. You’re meeting them again, and it’s like seeing someone you’ve missed for a very long time.”

Avery was acutely aware of the distance between her and Grant. It was strange. She could tell he was trying to say something meaningful, but it was as if he needed the barrier of the water between them to do it. She wasn’t entirely sure what he was talking about, but the gist of it was that he felt a special connection to her—and she realized that was what he had meant all along. That was what he had meant when he’d said there was something special about her. She was flattered, but also wary.

Grant watched her, waiting for some response. Finally he said, “What are you thinking?”

Avery stripped out of her clothes down to her bra and panties and waded into the water. When she reached Grant, he took her hand in his and then stepped closer and put his arms around her. She let him hold her for a moment without returning the embrace, as if she were thinking about something else. Then he took her head in his hands and kissed her, and again she let him. When his hands slid down the small of her back to grasp her and pull her into him, she didn’t resist. She felt him stiff and warm pressing against the bare skin of her stomach. “Hey,” she whispered, meaning to turn down the heat of the moment, but no other words came, and when he lifted her up and carried her back to the shore, she laughed, partly like a child laughing at being lifted and carried and partly in amazement at the power in his arms and chest and thighs. She recognized both excitement and fear at the strength in him as he carried her out of the water and onto the shore, where he pushed her back against a tree, the rough bark scraping the soft skin between her shoulders. She tried to speak, meaning to ask him with humor just what he thought he was doing, but he kissed her again, hard, and she kissed him back in a daze of sensation and movement and heat—and then, in an instant, his foot hit the inside of her ankle and pushed her leg aside as his hand simultaneously reached between her legs, and then he was inside her with a single movement that made her gasp, partly in shock at the ease of the entry and partly out of simple surprise and unreadiness.

She said his name aloud, sure the urgency in her voice would make him stop, and when he didn’t, she said it again, louder, a command—but instead of stopping, he brought his right hand up around her neck, his thumb and forefinger digging into either side of her jaw, and pressed her head back against the tree as he pushed harder and deeper. His hand around her neck terrified her, and her body went slack with surrender. There was, then, the briefest of moments that felt like a hinge, an instant in which things might swing one way or another: in one direction, screams, scratching and fighting; in the other, abandon, immersion in movement and feeling. Even though the moment was so fleeting it barely happened, she recognized it with an out-of-body clarity, that hinge moment, a point of turn. She made her choice by grabbing his ears as if she might rip them off and locking her calves around his thighs as she pushed back against his push with equal power. His hand came away from her neck and he was thrown backward as he spun around, holding her in the air a moment before kneeling and laying her down in the bed of moss, cool and wet against her skin. Under him, on her back, she grasped his ears tightly, her fingernails digging into them while he continued pushing as if he were desperate to reach up into her belly. When she yanked his head up to see his face, she found a turbulent mix of pain and pleasure there. Inside her she felt the familiar build of heat and sensation, and she willed herself into it until, finally, it released and washed over her, accompanied by a long guttural note, half growl, half moan.

On top of her, inside her, Grant kept at it until he was done. When he got up and walked away, Avery closed her eyes, turned on her side, and curled up into herself. Outside the blind circle she identified as her body, she could hear Grant getting dressed, the sound of clothes sliding over limbs, the rattle of a belt buckle.

After sex, she usually wanted more of a man, she wanted to be held while he was still inside her, but now she was content with the feel of moss under her cheek and the low, rustling half whistle of wind through leaves. She didn’t want to think. All she wanted was to lie there quietly with the sound of wind and the odd, dreamy sensation of movement that she knew was an illusion but felt real, a sensation of sliding and sinking as if everything outside her were drifting away and she was falling backward into a dark space. In her mind’s eye, she saw herself lying on the ground while Grant stood over her, watching her. In her mind, she saw him scowling, and when she opened her eyes, there he was, just as she had imagined, standing close by and looking down at her—only he wasn’t scowling. She couldn’t name the expression on his face except that at first it seemed impassive, merely observing—and then in the instant after she opened her eyes, it changed to a smirk, and he turned his back to her and walked off along the path toward his bike, leaving her where she lay, a white body curled up on a bed of dark green moss. She didn’t get up until she heard the roar of the motorcycle engine behind her, and only then because she thought it was possible that he might simply drive off and leave her there—but when she came up off the trail, he was waiting for her astride his bike, his helmet pulled down over his head, his face hidden behind the black mask. She pulled on her own helmet and pulled down the mask, and they drove off without a word, her arms again wrapped around him, the bike again speeding over dark roads.