Читать книгу The Traumatic Colonel - Ed White - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Ancient historians compiled prodigies, to gratify the credulous curiosity of their readers; but since prodigies have ceased, while the same avidity for the marvelous exists, modern historians have transferred the miraculous to their personages.

—Charles Brockden Brown, “Historical Characters Are False Representations of Nature”

In November 1807, six years into retirement from the presidency, John Adams spelled out for his regular correspondent Benjamin Rush his thoughts about the tremendous and mysterious popularity of George Washington. He ventured to outline ten qualities that explained Washington’s “immense elevation above his fellows”: his “handsome face”; his height; his “elegant form”; his grace of movement; his “large, imposing fortune”; his Virginian roots (“equivalent to five talents,” he added parenthetically); “favorable anecdotes” about his earlier years as a colonel; “the gift of silence”; his “great self-command”; and finally the silence of his admirers about his flaws, particularly his bad temper.1 “Here you will see,” he concluded, “I have made out ten talents without saying a word about reading, thinking, or writing. . . . You see I use the word talents in a larger sense than usual, comprehending every advantage. Genius, experience, learning, fortune, birth, health are all talents” (107).

This was far from the first time Adams had tried to explain Washington’s status, a topic that had arisen regularly since Adams and Rush began their correspondence in early 1805. At one point he stressed the hypocrisy of those “who trumpeted Washington in the highest strains” but who “spoke of him at others in the strongest terms of contempt” (January 25, 1806, 49).2 Later he emphasized a public complicity in certain fictions of Washington’s life, such that his professed “attachment to private life, fondness for agricultural employments, and rural amusements were easily believed; and we all agreed to believe him and make the world believe him” (September 1807, 101). At another point he stressed the class-motivated theatrics “played off in the funerals of Washington, Hamilton, and Ames,” which are “all calculated like drums and trumpets and fifes in an army to drown the unpopularity of speculations, banks, paper money, and mushroom fortunes” (July 25, 1808, 123–24). Washington’s acting abilities deserved mention too, for “we may say of him, if he was not the greatest President, he was the best actor of presidency we have ever had,” even achieving “a strain of Shakespearean and Garrickal excellence in dramatical exhibitions” (June 21, 1811, 197). So too the clever financial maneuverings beneath Washington’s alleged “sacrifices,” such that “he raised the value of his property and that of his family a thousand per cent, at an expense to the public of more than his whole fortune” (August 14, 1811, 201). As late as 1812, Adams was stressing Washington’s special status as a “great character,” “a Character of Convention,” explaining, “There was a time when northern, middle, and southern statesmen and northern, middle, and southern officers of the army expressly agreed to blow the trumpet of panegyric in concert, to cover and dissemble all faults and errors, to represent every defeat as a victory and every retreat as an advancement, to make that Character popular and fashionable with all parties in all places and with all persons, as a center of union, as the central stone in the geometrical arch” (March 19, 1812, 230, emphasis in original). A similar process was under way in France with Napoleon, and “something hereafter may produce similar conventions to cry up a Burr, a Hamilton, an Arnold, or a Caesar, Julius or Borgia. And on such foundations have been erected Mahomet, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane, Kublai Khan, Alexander, and all the other great conquerors this world has produced” (ibid.).

This range of observations should illustrate the uncertainty and inconsistency of Adams’s speculations, which were by no means confined to Washington. Indeed, the topic of reputation and mystique seems to have been prompted by comments exchanged in 1805, about the Spanish American adventurer Francisco de Miranda. Adams had written Rush of “a concurrence, if not a combination, of events” that struck him (December 4, 1805, 47). “Col. Burr at Washington, General Dayton at Washington, General Miranda at Washington, General Hull returning from his government, General Wilkinson commanding in Louisiana, &c., &c.” (ibid.). Rush answered that Miranda had in fact recently paid a visit and had reminded him, “in his anecdotes of the great characters that have moved the European world for the last twenty or thirty years, of The Adventures of a Guinea, but with this difference—he has passed through not the purses but the heads and hearts of all the persons whom he described” (January 6, 1806, 48). “I never had the good fortune to meet General Miranda nor the pleasure to see him,” answered Adams:

I have heard much of his abilities and the politeness of his manners. But who is he? What is he? Whence does he come? And whither does he go? What are his motives, views, and objects? Secrecy, mystery, and intrigue have a mighty effect on the world. You and I have seen it in Franklin, Washington, Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson, and many others. The judgment of mankind in general is like that of Father Bouhours, who says, “For myself, I regard secret persons, like the great rivers, whose bottoms we cannot see, and which make no noise; or like those vast forests, whose silence fills the soul, with I know not what religious horror. I have for them the same admiration as men had for the oracles, which never suffered themselves to be understood, till after the event of things; or for the providence of God, whose conduct is impenetrable to the human mind” (January 25, 1806, 49).

A few months later, Adams returned to these observations with this outburst: “Secrecy! Cunning! Silence! voila les grands sciences de temps modernes. Washington! Franklin! Jefferson! Eternal silence! impenetrable secrecy! deep cunning! These are the talents and virtues which are triumphant in these days,” he concluded, quickly adding, “When I group Washington with Franklin and Jefferson, I mean only in the article of silence” (July 23, 1806, 64).

How are we to read these exchanges? Let us start by considering two likely responses of contemporary readers. On the one hand, we might enjoy a certain gratifying titillation at hearing perhaps unknown, gossipy details about the Founding Fathers. This pleasure results not only from a familiarity with the Founders but also from a certain defamiliarization, as these mythical figures are made somewhat new. At the same time, however, many readers—above all, scholars—may feel a certain distaste at the continued fetishization of the elites of the past. After all, hasn’t much scholarship of the past century tried to move us away from such historiography, toward social or structural histories? Isn’t the history of the early republic to be found in histories from below, in the lives of women, workers, farmers, slaves, and Native Americans, rather than in the same old arcana of a few white, male elites? Isn’t a return to Adams’s musings about Washington and others somehow reactionary, a sign of that irritating phenomenon known as “Founders Chic”? Shouldn’t this Founders Chic be resisted?3

We would note, first, that this combination of responses—of guilty pleasure and critical disgust, of fascination and of knowing better—perfectly characterizes the musings of Adams himself. In the letters with Rush, he simultaneously indulges in and resists the aura of the Founders. His persistent enumeration of humanizing details and secret histories, shared with Rush in order to puncture the mystique of the already mythically enhanced elites, simultaneously exposes and perpetuates their perplexing prominence. Indeed, we would argue that this particular affective combination is exactly what defines Founders Chic. Like Adams, those who succumb to Founders Chic imagine that others naively, blindly, uncritically admire and worship the Founders—whether they are the fools voting for Jefferson or the modern purchasers of a best-selling biography. But it is this complex of fascination, this desire to decipher and interpret an inexplicably compelling cultural formation, that defines the phenomenon, and to cure ourselves we must begin by acknowledging that the logic of debunking will not get us very far. As Roland Barthes realized upon completion of Mythologies, myth debunking had become a myth in itself, a classroom exercise that any student could execute with facility, but without any ultimate threat to myth itself.4 In short, the critique of myth is often essential to its enjoyment. Nor can we say that debunking is a later phenomenon. In the case of Founders Chic, the seemingly contrary tendency toward humanizing details, context, and “secret” histories was present from the start, an integral part of the formation of the Founders Fantasy. Thus, when contemporary hagiographies startle their readers by telling them, first, the shocking details of a Jefferson or a Franklin and, second, that lo and behold these details actually appeared in the newspapers of the time!!, they fundamentally obscure the problem. This favorite rhetorical move makes one marvel at the Founders all the more, for they seem to have become larger than life despite knowledge of their sexual histories, their racial politics, or their political maneuvers. Actually the reverse is the case: the Founders emerged as significant symbolic figures because of these biographical, semic details.5 We see precisely this relationship in the Adams-Rush correspondence, in which the secret histories and private details of the Founders, dished to deflate their mystique, rather amplify it instead. This phenomenon is more pertinent than ever today, when ostensibly humanizing and demythologizing biographical details preserve and renew the Founders’ mythological status.6

If we want to cure ourselves of Founders Chic, then, we cannot have recourse to the details that fill the letters of Adams and Rush: they are part of the problem we need to address. Instead, we must focus on the formal insights indirectly articulated in these letters. Two related observations seem particularly important. The first is that the Founders are constituted by a carefully structured emptiness. Adams and Rush touch on this point again and again when they speak of the secrecy, silence, mystery, and intrigue that characterize such figures, when the Founders are compared to deep rivers and silent forests, or when Washington is described as a stone that fills a gap in a geometrical arch.7 These gaps are then restlessly filled by semic details. Adams’s list of Washington’s ten talents is exemplary of this manic overlay. And the observation that those who lauded Washington “in the highest strains” also held him in the “strongest terms of contempt” confirms that this content need not be consistent in fact or affect. Thus, vitriol, scandal, and rumor may as easily fill that empty space as heroic feats, gestures, and words. The point is that biographical details are subordinate to this fundamental structuring of the Founder figure.

Second, and consequently, we see Adams refer, again and again, to the Founders as fictional constructs. We see this in the references to the portrayal of Washington as “the best actor of presidency we have ever had” but even more so in the description of “a Character of Convention,” a phrase we should read in the most literal sense. Rush goes a step further in the comparison with the guinea, the object passed through numerous hands in the 1767 novel Chrysal; or, The Adventures of a Guinea. The point is clear: the Founders are imaginative fictions, characters in the specifically literary sense, whose circulation is essential for their constitution and whose significance in the narrative often results from narrative elements clustered around them. Narratological theory stresses this point by renaming characters “actants” to mark their structural position, an observation Adams approaches when he reflects on the “concurrence, if not a combination, of events” that links together Burr, Dayton, Miranda, Hull, and Wilkinson. This conjunction “strikes” Adams, as if he is unsure what this means, but he describes a process of overdetermination whereby characters draw semic material from the confluence of events. Here, it seems, one of the actants—perhaps Burr?—takes greater cohesion as it draws together the semiotic resources in circulation in late 1805. Instead of the usual historicist debunking (there are myths, but here are some facts that indicate the deeper truth) which reaffirms Founders Chic, Adams verges on formulating the reverse procedure: there are facts, yes, but here are some myths that indicate the deeper truth. The point, of course, is that we are not trying to get at an empirical phenomenon but rather at some very different kind of cultural manifestation, one requiring different methods and theoretical assumptions.

In this light, the very phenomenon of Founders Chic speaks to a disciplinary confusion that The Traumatic Colonel seeks to address. Rather than treating the Founders as actual agents who need to be more aggressively historicized with empirical data (true, but in a more limited sphere than often assumed), our starting point is that they are primarily imaginative, phantasmatic phenomena best explored from a broadly literary perspective—as a broad characterological drama whose plot often remains obscure. Accordingly, our approach in this work insists on a parallactic division of what we have been calling the historical and the literary. In recent theoretical work, the idea of the parallax has been most notably explored in Slavoj Žižek’s The Parallax View. Žižek’s immediate inspiration is the Japanese Marxist philosopher Kojin Karatani, who takes the term from Kant, who himself borrowed it from early modern astronomy. In its original formulation, “parallax” designated the change in position or direction of an object as seen from two different points: the parallax of a star or a planet was necessary for calculating its exact location. Used metaphorically, the term refers to the gap in perceptions of the same thing from different vantage points. Kant used the metaphor philosophically to denote the gap between common sense “from the standpoint of my own” and “from the point of view of others.” Hugh Henry Brackenridge, in the final volume of Modern Chivalry (1815), used the same metaphor to describe the gap between the political-theoretical differentiation of humans and animals and, from a more remote perspective, their similarities. For Karatani, the parallax view becomes the foundation for the proper form of criticism—what he calls transcritique—which is not analysis from a priori systems of thought (i.e., the application of theory) but rather a movement between two different theoretical registers—resulting in an antinomy. Philosophy proper is this transcritical reading of parallactic contexts—in Karatani’s project, a reading of Kantian philosophy alongside a seemingly incompatible Marxian political economy. Žižek expands this view of the parallax to propose it as the proper mode and orientation for cultural criticism. The parallax, understood as the constitutive rift in human perception, opens up the consideration of a host of theoretical aporia—he speaks of “an entire series of the modes of parallax in different domains of modern theory”—the most important of which is the parallax between Lacanian psychoanalysis and Marxism.8

In the most vulgar sense, the impulse to juxtapose these two theories aims to address the gap between the interior, psychic constitution of the subject and the objective, material forces of the historical moment. It is this gap that ideology always seeks to fill, stressing the continuities between the two spheres. A parallactic analysis, by contrast, resists such closure, insisting that the analysis of these two perspectives can only proceed if initially kept distinct. To take the Founding Fathers as an illustration, the problem with Founders Chic is that it collapses the distinction between the mythical-literary and the historical-empirical, as in the attempts to find the “man in the myth.” A parallactic view of the Founders would instead emphasize their mythical stature and accept this as one perspective worthy of analysis and requiring careful juxtaposition with, say, biographical or sociopolitical details. The point is not to fold the one into the other in an effort at synthesis but to explore how the parallactic distance between the two better helps us identify what we are seeing.

For Žižek, Jacques Lacan’s neologism “extimacy” best identifies this gap. The extimacy concept aims to solve the conundrum of theorizing “a cause that is both exceptional to the social field . . . and internal to the field.”9 As Molly Anne Rothenberg describes it in The Excessive Subject, the extimate addresses the aporia separating theories of immanent and external causation in the social field. The former, for which Michel Foucault serves as the most influential example, “treats causes and effects as mutually conditioning one another within the same field.”10 The latter, exemplified by certain kinds of Marxism, finds causes external to effects. Thus, an immanent account of the Founders might find a discourse of power unfolding and accumulating around a Thomas Jefferson, while an external account might posit a social system—say, the plantocracy—as the social cause for Jefferson’s hyperbolic discursive status. The problem with each position is its failure to address the other, particularly by considering the shift of the phenomenon in question from intimate to extimate spheres. The bind becomes clear in the frustrated musings of Adams and Rush. At times, they want to stick with an immanent analysis, as when they discuss Washington’s ten talents or his theatrical abilities: he is great because he performs greatness, has great skills, and so on. At other times, they opt for an external analysis—for instance in arguing that politicians decided to elevate the Virginian for political purposes. The inadequacy of these explanations comes through in their more complex attempts at commentary, as when Adams describes the mysterious aura of Washington. In this insightful argument, it is not that admirers of Washington perceive something properly within him, nor that he is puffed up by any particular social forces, but rather that Washington names an oracular site in which certain qualities are read and then received back again and so on in a constant feedback loop. Extimacy names this process, which is neither properly external nor internal and which exists precisely because “intimate” discourses must be externalized. In contrast to intimacy, which associates subjectivity with the private, interior self, extimacy, as Mladen Dolar puts it, names “the point of exteriority in the very kernel of interiority, the point where the innermost touches the outermost, where materiality is the most intimate.”11 Such is the point of Žižek’s most fundamental claim: “the Unconscious is outside, not hidden in any unfathomable depths—or to quote the X Files motto: the truth is out there.”12

The Traumatic Colonel ventures the first steps in an extimate history of the Founders, along the lines of what Adams called “Character[s] of Convention.” What is their history? When were they created and in relation to what narratives, what other characters? Chapter 1 begins with this task, offering a basic literary history of the formation of the four major figures: Washington, Franklin, Hamilton, and Jefferson. The emergence of this particular constellation was slow and halting and extends from a preliminary moment in the mid-1770s to the much more significant decade from about 1796 to 1806. As we outline this argument, it will become clear that we take the literary dimensions of our argument seriously, for we are convinced that imaginative works can help us better situate and understand the formulation of the Founders. Accordingly, we follow our initial speculations on the Founders with detailed explorations of two early American novels—Charles Brockden Brown’s Ormond (1799) in chapter 2 and Tabitha Gilman Tenney’s Female Quixotism (1801) in chapter 3—as further guides to this process. Brown’s novel, we argue, predicts the dynamic operation of the Founders system, while Tenney’s novel carefully and insightfully maps its emergence and political mobilization. Just as importantly, however, we want to insist on an expanded sense of imaginative literature that includes not just novels such as Brown’s and Tenney’s but the rich and significant political literature—the pamphlets, polemics, tracts, and biographies—of the early republican period. To that end, we try to reimagine a literary history that might accommodate works such as John Wood’s The History of the Administration of John Adams (1802) or James Cheetham’s A View of the Political Conduct of Aaron Burr, Esq., of the same year. We even speculate that this flourishing of political writing may help us fill the notorious gap in US literary history, between 1800 and 1820.

But literary analysis is not an end in itself here. It is rather an exploration of a medium in which the dynamics of political fantasy are more easily grasped. Such dynamics are essential to our readings of the two proper novels, which we read as complementary explications of an emerging fantasy at the heart of US political culture, but this analysis allows us to take up the figure of Aaron Burr, the “traumatic colonel” of our title. The thing called Burr has a particular interest for us as the distinctively anomalous figure hovering at the margins of the Founders proper. So we will be arguing that the significance of Burr is precisely its resistance to incorporation in the semiotic system of the Founders. This is an argument broached in chapter 2 but explored in detail in chapter 4, where we outline the articulation of the Burr in the years between 1799 and 1804. In so doing, we try to make sense of those odd details that have proven so fascinating in contemporary literature of the Founders: Burr’s electoral tie with Thomas Jefferson in 1800, the accusations of seduction, the assault waged by the New York Republicans, the duel with Alexander Hamilton, and the Federalists’ odd courting of their hated antagonist to lead a secession movement. Chapter 5 examines the ramifications of this argument, as the uncertain fascination with Burr suddenly coalesced, between 1805 and 1807, into a major conspiratorial fantasy and a notorious treason trial that uncannily reassembled the former leaders of the Revolution. Burr’s formation; his brief circulation through and around the symbolic field of the Founders; the repeated attempts to assimilate him as a Founder figure; the ultimate, violent repudiation and expulsion of this figure—together these reveal Burr to be the traumatic colonel of the Founders constellation. In this respect, Burr is indeed the cipher it was repeatedly described as being, with an emphasis on both meanings of that term, code and key.

This brings us to our third objective, namely, a new historical perspective on the early republican period informed by the Burr and the literary and phantasmatic elements it designates. Rush and Adams hint at this argument when they note the conjunctions of late 1805, though they miss the crucial reference: Toussaint L’Ouverture, dead in France in 1803. In short, we will be arguing that the history of Burr in relation to the Founders clarifies the complex processing of the great crime of slavery, its increased political institutionalization with the election of the “Negro President,” its likely extension with the Louisiana Purchase, and through all this the enormous threat posed by the Haitian Revolution to the US South. This is an argument slowly developed throughout The Traumatic Colonel, first in a reading of the racial dimensions of the Founders constellation, then in an insistence on the important racial subtexts of Ormond and Female Quixotism. Chapters 4 and 5 then aim to situate Burr’s rise and fall as a coded response to the consolidation of slavery, such that Burr, the imagined renegade conspirator of a breakaway empire, stands revealed as Toussaint in whiteface. The story of Burr, then, is one important story of the US engagement with Haiti.

This brings us, finally, to another reorientation central to The Traumatic Colonel—that of periodization. Scholarship of the early republic has remained firmly focused on the 1790s, that most historiographically privileged of decades. The 1790s, particularly among literary scholars, have been understood as the pivotal moment of intense ideological division between left and right, a brief moment of the flourishing of radicalism, and a literary boom period before the lull heralding the Era of Good Feelings. Such a focus has fit well with the field’s recent emphasis on nationalist anxieties, the novel, and circumatlantic exchange, in which literary histories have foregrounded the national allegory and transnational affiliations in a cluster of novels from the decade. While we do not dispute the insights of this scholarship, it is worth considering the name that older anthologies gave to this decade—the Federalist Era—and how it may recontextualize our framing of the broader expanse from 1780 to 1820. For from the vantage point of 1808 and the official cessation of the Atlantic slave trade, the 1790s appear to be anomalous, an unusual hiatus in the long consolidation of power by the plantocracy in its alliance with northern workers. Washington’s iconic preeminence guaranteed eight years of rule during which Federalism forged its uneasy compromise with slavery and partisan organization slowly emerged. The continuation of Federalist rule under Adams—facilitated by the still disorderly electoral system—was then the only presidency of a non-Virginian until the messy election of 1824. Given the solid rule by Virginian slaveholders, we might see the overall period as one of the consolidation of a slavery power, with the Louisiana Purchase a high point signaling the extension of human bondage to points south and west; with the Northwest Ordinance of 1785, ensuring a slave-free territory, a crucial exception, matched in foreign policy by the debates over the Toussaint Clause; or with the 1808 nonimportation legislation as the trigger for a doubling down of the slave powers.

To be sure, discussions of the 1790s have not been silent about race, whether in biographical accounts (e.g., discussions of Jefferson), local histories (such as the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia), or treatment of the world-historical impact of the Haitian Revolution. Indeed, much circumatlantic scholarship has followed Paul Gilroy and others in stressing a Black Atlantic, and we have been inspired by an impressive number of works exploring the centrality of enslavement to US cultural politics. These include older studies such as Winthrop Jordan’s White over Black and David Brion Davis’s writings, as well as such recent focused studies as Leonard L. Richards’s The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780–1860 (2000), David Waldstreicher’s Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution (2004), Henry Wiencek’s An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (2003), Gordon S. Brown’s Toussaint’s Clause: The Founding Fathers and the Haitian Revolution (2005), and Ashli White’s Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic (2010). As important have been such new syntheses treating slavery as Garry Wills’s Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power (2003), Alfred W. Blumrosen and Ruth G. Blumrosen’s Slave Nation: How Slavery United the Colonies and Sparked the American Revolution (2006), Matthew Mason’s Slavery and Politics in the Early American Republic (2006), Peter Kastor’s The Nation’s Crucible: The Louisiana Purchase and the Creation of America (2004), Adam Rothman’s Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South (2005), Eva Sheppard Wolf’s Race and Liberty in the New Nation: Emancipation in Virginia from the Revolution to Nat Turner’s Rebellion (2006), Craig Hammond’s Slavery, Freedom, and Expansion in the Early American West (2007), and Mason and Hammond’s Contesting Slavery: The Politics of Bondage and Freedom in the New American Nation (2011). Also significant has been a wave of cultural-critical works including Dana Nelson’s The Word in Black and White: Reading “Race” in American Literature (1992), Leonard Cassuto’s The Inhuman Race: The Racial Grotesque in American Literature and Culture (1997), Jared Gardner’s Master Plots: Race and the Founding of an American Literature, 1787–1845 (1998), Philip Gould’s Barbaric Traffic: Commerce and Antislavery in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (2003), David Kazanjian’s The Colonizing Trick: National Culture and Imperial Citizenship in Early America (2003), Gesa Mackenthun’s Fictions of the Black Atlantic in American Foundational Literature (2004), Sharon M. Harris’s Executing Race: Early American Women’s Narratives of Race, Society, and the Law (2005), Andy Doolen’s Fugitive Empire: Locating Early American Imperialism (2005), the roundtable “Historicizing Race in Early American Studies” published in Early American Literature (2006, ed. Sandra Gustafson), Sean Goudie’s Creole America: The West Indies and the Formation of Literature and Culture in the New Republic (2006), Robert S. Levine’s Dislocating Race and Nation: Episodes in Nineteenth-Century American Literary Nationalism (2008), Agnieszka Solysik Monnet’s The Poetics and Politics of the American Gothic: Gender and Slavery in Nineteenth-Century American Literature (2010), and the special issue of Early American Literature “New Essays on ‘Race,’ Writing, and Representation in Early America” (2011, ed. Robert S. Levine).

These works have variously attempted to expand our understanding of the workings of slavery as an expansionist economic force and political program, but they are perhaps as important for the ways in which they foreground the interpretive challenges of understanding the United States as a slave nation. The Blumrosens, for instance, recast the Revolutionary political narrative as one of often indirect responses to the Somerset case, from the early 1770s to the Northwest Ordinance and the framing of the Constitution: as such, they insist on a reprioritized hermeneutic at odds with the usual practices of intellectual history. Garry Wills similarly foregrounds a minority yet substantial political discourse of the “federal ratio” and “Negro President,” clarifying what these terms meant for an antislavery analytic buried beneath a “national reticence.”13 Or, to take another example, Mason’s account of political struggles pre-1808 simultaneously stresses the ways in which consideration of slavery “insinuated itself into a wide array” of issues but also ways in which the analysis of slavery remained incomplete and unarticulated, in many instances beyond agents’ ability to formulate them coherently.14

What many of these works have in common, then, is a dual appreciation of the importance of slavery and a methodological awareness, even insistence, on its discursive elusiveness, which is variously explained through recourse to obfuscation, reticence, emergence, confusion, code, or even impossibility. Several years ago, the last term was something of the doxa in many US discussions of the Haitian Revolution, the discourse of which was simultaneously silenced or (in Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s term) “unthinkable.”15 But a decade’s worth of excavatory scholarship has perhaps confirmed that parts of the Haitian Revolution were thinkable, even if difficult to articulate, such that a major challenge we face today is not just the (historical) thinking about the moment but a better understanding of its distorted articulation. We thus follow the lead of Colin Dayan and Sybille Fischer, whose pathbreaking books have allowed critics to read for historical memory and agency beyond the textual record. For Dayan, vodou combines both intimate and communal religious enthusiasm to the political unconscious, while Fischer uses the psychoanalytic language of disavowal to make the gaps and absences of memory and cultural production legible.16 Comparison may here be drawn to revisionist interpretations of American gothic literature, in which a racial subtext is regarded as constitutive of more explicit narrative and thematic aims.17 It is in this vein that we try to read the political discourse of the era. Matthew Mason concludes his chapter “Slavery and Politics to 1808” with the observation that the Burr Conspiracy “engrossed Americans more than the slave trade debates did” and that “only thereafter” did it become “clear that slavery was the prime threat to the federal compact.”18 We would less dispute these claims, taken in their most literal sense, than note that the Burr Conspiracy was so engrossing because it was essentially a coded, indirect drama about slavery and slave revolution. And if slavery’s threat to the federal compact became clear in the aftermath, it was in part due to the revelatory distortions of the preceding decade. In this respect, our study of the Burr phenomenon is offered as an attempt to explore the coded racialization of US cultural discourse, in keeping with the imperative presented in Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark.19

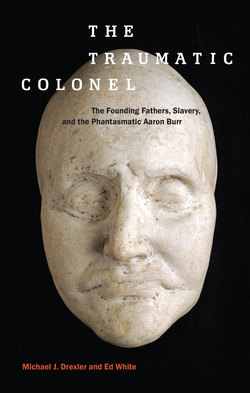

Perhaps the best emblem of our project may be found in Aaron Burr’s death mask, now in the Laurence Hutton Collection at Princeton University. Hutton had acquired the mask but was not sure of its provenance: “I had no special admiration for Burr—who once killed a Scotsman,—but I had all the collector’s enthusiasm for Burr in plaster and I wanted to think my Burr was Burr.”20 But Hutton had met the person who had secretly made the mask, working as the agent for the best-known popularizers of phrenology, Orson Squire Fowler, Lorenzo Niles Fowler, and Samuel Roberts Wells. As Hutton noted, the Fowlers had found in the Burr mask evidence that his “destructiveness, combativeness, firmness, and self-esteem were large, and amativeness excessive.”21 Indeed, Orson Fowler, in his massive Sexual Science, dwelt on Burr’s massive amativeness, adding this story about the crafting of the mask. The “posterior junction with the neck” was, in Burr, so large “that when his bust was taken after death, the artist took his drawing-knife to shave off what he supposed to be two enormous wens, but which were in reality the cerebral organs of Amativeness.”22 The excitement of discussing the death mask is such that it evokes anecdote after anecdote, two of which may be shared here. One is the story of Burr’s experiment with a life mask, apparently following the example of his then British host Jeremy Bentham. The mask was taken by the Italian-Irishman Peter Turnerelli, who reportedly left a small stain on Burr’s nose that he could not remove. The other is this story from Hutton:

A proud young mother once exhibited to me her new-born and first-born babe, now a blooming and pretty young girl. I was afraid to touch it, of course, and I would not have “held” it for worlds; but I looked at it in the customary admiring way, wondering at its jelly-like imbecility of form and feature. Alas! when I was asked the usual question, “Whom does she favour?” I could only reply, in all sincerity, that it looked exactly like a pink photograph of my death mask of Aaron Burr. And the young mother was not altogether pleased.23

The phrenological framing, belied by the “jelly-like imbecility of form and feature” of the unformed baby, may be read as the pseudoscientific codification, decades after its career, of the thing called Burr. And where “amativeness” looms ever larger—just as it does in racial discourse—there is a subtle constant concern with color through these details: the white mask, the dark stain caused by the life mask, the pinkish baby face. In Hutton’s Portraits in Plaster, Burr is brought up near the end, immediately preceded by considerations of the masks of Washington, Franklin, and Jefferson. Discussion of Burr is then followed immediately by consideration of the masks of Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Abraham Lincoln, as if Hutton is staging some strange theatrical version of the Civil War played out in masks. Two more masks remain—first, that of Lord (Henry) Brougham, a contemporary of Burr and active within British abolition, and then, finally, oddly yet not so oddly, the “Florida Negro Boy.” Why end with this boy, “one of the lowest examples of his race”? Hutton insists that “his life-mask is only interesting here as an object of comparison,” for “whatever the head of a Bonaparte, a Washington, a Webster, or a Brougham is, his head is not.”24 The boy from Florida thus emerges as the point of comparison, the uninteresting illustration so powerful that it must conclude Hutton’s book, the puzzle and its own solution, the conclusion of the sequence that takes us from Washington to Burr and on to Lincoln.