Читать книгу Hokusai - Edmond de Goncourt - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I. Life of Hokusai

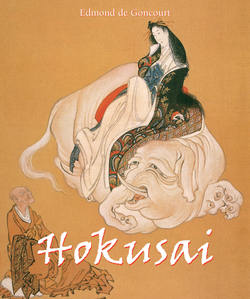

ОглавлениеBlue Kongō (Seimen Kongō), 1780–1790.

Nishiki-e, 37.3 × 13.7 cm.

Honolulu Academy of Arts, donation of James A. Michener, Honolulu.

Hokusai was born in 1760 (October or November according to some, March according to others). He was born in Edo in the Honjô neighbourhood, close to the Sumida River and to the countryside, a neighbourhood to which the painter was much attached. He even signed his drawings, for a time, “the peasant from Katsushika”, Katsushika being the provincial district where the Honjô neighbourhood is located. According to the will left by his granddaughter, Shiraï Tati, he was the third son of Kawamura Itiroyemon, who, under the name Bunsei, would have been an artist of the new profession. Near the age of four, Hokusai, whose first name was Tokitaro, was adopted by Nakajima Isse, mirror designer for the Tokugawa royal family.

Hokusai, while still a child, became the assistant to a great bookseller in Edo, where while contemplating illustrated books, he carried out his duties as assistant so lazily and disdainfully that he was fired. Paging through the bookseller’s illustrated books and life in images for long months developed the young man’s taste and passion for drawing. Around 1773–74, he worked for a woodcutter, and in 1775, under the name Tetsuro, he engraved the last six pages of a novel by Santchô. Thus, he became a woodcutter, which he continued until the age of eighteen.

In 1778, Hokusai, then named Tetsuzo, abandoned his profession as a woodcutter. He was no longer willing to be the interpreter, the translator of another’s talent. He was taken by the desire to invent, to compose, and to give a personal form to his creations. He had the ambition to become a painter. He entered, at the age of eighteen, the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō, where his budding talent earned him the name of Katsukawa Shunrō. There, he painted actors and theatre sets in the style of Tsutzumi Torin and produced many loose-leaf drawings, called kyōka surimono. The master allowed him to sign, under this name, his compositions representing a series of actors, in the upright format of the drawings of actors by Shunshō, his master. At this time, the young Shunrō began to show a bit of the great sketch artist who would become the great Hokusai. With perseverance and relentless work, he continued to draw and to produce, until 1786, compositions bearing the signature of Katsukawa Shunrō, or simply, Shunrō.

In 1789, the young painter, at twenty-nine years old, was forced to leave Katsukawa’s studio under peculiar circumstances. As a matter of fact, Hokusai would keep the odd habit of perpetually moving and of never living more than one or two months in the same place. This departure took place under the following circumstances: Hokusai had painted a poster of a stamp merchant. The merchant was so happy with the poster that he had it richly framed and placed in front of his shop. One day, one of his fellow students at the studio, who had studied there longer than he, passed the shop. He thought the poster was bad and tore it down to save the honour of the Shunshō studio. A dispute ensued between the elder and the younger student, following which Hokusai left the studio, resolving to work only from his own inspiration and to become a painter independent of the schools that preceded him. In this country where artists seem to change names almost as often as clothes, he abandoned the signature of Katsukawa to take that of Mugura, which means shrub, telling the public that the painter bearing this new name did not belong to any studio. Completely shaking off the yoke of the Katsukawa style, the drawings signed Mugura are freer and adopt a personal perspective.

Hokusai married twice, but the names of his two wives are unknown. It is also not known whether or not his separation from them was due to death or divorce. It is certain that the painter lived alone after the age of fifty-two or fifty-three. By his first wife, Hokusai had a son and two daughters. His first son, Tominosuke, took over the house of the mirror designer Nakajima Isse and led a disorderly life, causing his father many problems. His daughter Omiyo became the wife of the painter Yanagawa Shighenobu. She died shortly after her divorce and after having given birth to a grandson who was a source of tribulation for his grandfather. His second daughter Otetsu was a truly gifted painter who died very young. By his second wife, Hokusai also had a son and two daughters. His second son, Akitiro, was a civil servant of the Tokugawa rule and a poet, and became the adopted son of Kase Sakijiuro. He erected Hokusai’s tomb, and took on his name. The grandson of Takitiro, named Kase Tchojiro, was the schoolyard friend of Hayashi, a great collector of Japanese art. Hokusai’s other daughters were Onao, who died in her childhood, and Oyei, who married a painter named Tomei but divorced him and lived with her father until the end of his life. She was an artist, who illustrated Onna Chohoki, an educational book for women covering etiquette. Hokusai had two older brothers and a younger sister, who all died in their childhood.

His life was filled with pitfalls. Thus, near the end of 1834, serious problems arose in the old painter’s life. Hokusai’s daughter Omiyo married the painter, Yanagawa Shighenobu. From this marriage came a veritable good-for-nothing, whose swindles, always paid by Hokusai, were the cause of his misery during his last years. It is plausible that, following commitments made by the grandfather to keep his grandson from going to prison, commitments that he could not keep, he was forced to leave Edo in secret, to take refuge more than thirty leagues from there in the Sagami province, in the city of Uraga, hiding his artistic name under the common name of Miuraya Hatiyemon. Even upon returning to Edo, he did not dare, at first, give out his address and called himself the “priest-painter”, and moved into the courtyard of the Mei-o-in temple, in the middle of a small forest. From this exile, which lasted from 1834 to 1839, remain some interesting letters from the painter to his editors. These letters attest to the old man’s trials caused by his grandson’s mischief, and to the destitution of the great artist, who complained, one harsh winter, of having only one robe to keep his septuagenarian body warm. These letters unveil his attempts to soften his editors, through the melancholy exposition of his misery, illustrated with nice sketches. They also unveil some of his ideas on translating his drawings into woodcuts, initiated in the language marked by crude images with which he was able to make the workers charged with printing his works understand the way to obtain artistic prints.

Kabuki Theater in Edo seen from an Original Perspective, c. 1788–1789.

Nishiki-e, 26.3 × 39.3 cm.

The British Museum, London.

Kintoki the Herculean Child with a Bear and an Eagle, c. 1790–1795.

Ōban, nishiki-e.

Ostasiatische Kunstsammlung, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin.

The year 1839, which followed three years of poor rice harvests, was a year of scarcity during which Japanese restrained their spending and no longer bought images and where editors refused to cover the publication costs of a book or a single plate. During this editors’ strike, Hokusai, counting on the popularity of his name, had the idea of composing albums from “the tip of his brush”, and he earned about what he needed to live during this year from the sale of these original drawings, undoubtedly sold very cheaply. It was in 1839 that Hokusai returned to Edo, after four years of exile in Uraga. But this was another miserable year for the artist. He had only just moved in, again settling in Honjô, the country neighbourhood that the painter loved, when a fire burnt his house; it destroyed many of his drawings, outlines, and sketches, and the painter was only able to save his brush.

At the age of sixty-eight or sixty-nine, Hokusai had an attack of apoplexy, from which he emerged by treating it with ‘lemon curd’, a remedy in Japanese medicine, whose composition was given by the painter to his friend Tosaki, with sketches in the margin of the prescription representing the lemon, the knife for cutting the lemon, and the pot. Here is the composition of this ‘lemon curd’: “Within twenty-four Japanese hours (forty-eight hours) of the attack, take a lemon and cut it into small pieces with a bamboo knife, not an iron or copper one. Put the lemon, thus cut, into a clay pot. Add a go (one quarter litre) of very good sake and let it cook over low heat until the mixture thickens. Then, you must swallow, in two doses, the lemon curd, after removing the seeds, in hot water; the medicinal effect will take place after twenty-four or thirty hours.” This remedy completely cured Hokusai and seems to have kept him healthy until 1849, when he fell ill at ninety years old, in a house in Asakusa, the ninety-third home in his vagabond life of moving from one house to another. This is, undoubtedly, when he wrote to his old friend Takaghi this ironically allusive letter: “King Yemma is very old and is preparing to retire from business. He has built, to this end, a pretty country house and he has asked me to go paint him a kakemono. I am thus obliged to leave, and when I do leave, I will take my drawings with me. I will rent an apartment at the corner of Hell Street, where I will be happy to have you visit if you have the occasion to stop by. Hokusai.”

The Actor Ichikawa Yaozō III in the Role of Soga no Gorō and Iwai Hanshirō IV in the Role of his Mistress, Sitting, 1791.

Hosoban, nishiki-e.

Japanese Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto.

The Actor Ichikawa Omezō in the Role of Soga no Gorō, 1792.

Nishiki-e, 27.2 × 12.7 cm.

Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden.

The Actor Ichikawa Ebizō IV, 1791.

Nishiki-e, 30.8 × 14 cm.

National Museum of Tokyo, Tokyo.

The Actor Sakata Hangorō III, 1791.

Nishiki-e, 31.4 × 13.5 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, William Sturgis Bigelow Collection, Boston.

At the time of his last illness, Hokusai was surrounded by the filial love of his students, and was cared for by his daughter Oyei, who had divorced her husband and was living with her father. The thoughts of the dying “crazy artist”, always trying to defer his death to perfect his talent, made him repeat in a voice that was no longer more than a whisper, “if heaven would only give me ten more years…” There, Hokusai broke off, and after a pause, “if heaven would only give me five more years of life… I could become a truly great painter.”

Hokusai died at the age of ninety, on the eighteenth day of the fourth month of the second year of Kayei (10 May, 1849). The poetry of his last moment, as he left in death, is almost untranslatable: “Oh! Freedom, beautiful freedom, when one goes into the summer fields to leave his perishable body there!” Another tomb was erected for him by his granddaughter, Shiraï Tati, in the garden of the Seikioji temple of Asakusa, next to the gravestone of his father, Kawamura Ïtiroyemon. One can read on the large gravestone: Gwakiojin Manjino Haka (Tomb of Manji, crazy old artist); on the base: Kawamura Uji (Kawamura family). On the left side of the gravestone, at the top, are three religious names: Firstly, Nanso-in Kiyo Hokusai shinji (the knight of the faith, Hokusai in colourful glory), Nanso (a religious figure from the South of So); Secondly, Seisen-in Hō-oku Mioju Shin-nio, the name of a woman who died in 1828, who may be his second wife; and thirdly, Jô-un Mioshin Shin-nio, another name of a woman who died in 1821, that of one of his daughters.

It is uncertain as to whether or not there is an existing authentic portrait of the master. The portrait of Hokusai, together with the novelist Bakin, after a stamp by Kuniyoshi, is no longer a portrait, as the sketch represents him kneeling, offering the editor his little yellow book, “The Tactics of General Fourneau”, or of “Improvisational Cuisine”. Of the great artist, there are no childhood or adult portraits. The only existing portrait is the one given by the Japanese biography by Iijima Hanjuro, a portrait of him as an old man, preserved in the family and which had been painted by his daughter Oyei, who signed Ohi. One sees a forehead furrowed by deep wrinkles, eyes marked by crow’s feet with swollen bags beneath them, and there is, in the half closed eyes, some of that mist that sculptors of netzukes place in the look of their ascetics. The man has a large, bony nose, a thin mouth tucked under the fold of his cheeks and the square chin of a strong will, connected to his neck by wattles. The colouring of the image, which matches the tone of old flesh fairly well, renders well the anaemic pallor of the bags under his eyes, around his mouth, and of his earlobes. What is striking about the face of this man of genius is its length, from his eyebrows to his chin and the low height and dented top of his head, with, at the temples, a few rare little hairs resembling the young grass in his landscapes. Another portrait of Hokusai, of which a facsimile was published in the Katsushika den, represents him near the age of eighty, next to a pot, crouching under a blanket, showing the profile of an old head shaking and of thin legs. Here is the origin of this portrait: the editor Szabo ordered the illustration of the “Hundred Poets”, from Hokusai. The artist, before starting his work, sent a sample to determine the format of the publication, and on this sample, his brush left this “caricature”.

Actors Ichikawa Kōmazu II and Matsumoto Koshirō IV, c. 1791.

Nishiki-e diptych, each sheet: 32 × 14 cm.

Ginza Tokyo Yôkan Collection, Tokyo.

A Mare and her Foal, 1795–1798.

Nishiki-e, 35.5 × 24 cm.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

The style called Hokusai-riu is the style of true Ukiyo-e painting, naturalist painting, and Hokusai is the one and only founder of a painting style that, based on Chinese painting, is the style of the modern Japanese school. Hokusai victoriously lifted up paintings of his country with Persian and Chinese influences, and by a study one might call religious in nature, rejuvenated it, renewed it, and made it uniquely Japanese. He is also a universal painter, who, with very lively drawings, reproduced men, women, birds, fish, trees, flowers, and sprigs of herbs. He completed 30,000 drawings or paintings. He is also the true creator of the Ukiyo-e, the founder of the ‘école vulgaire’, which is to say that he was not content to imitate the academic painters of the Tosa school, with representing, in a precious style, the splendour of the court, the official life of high dignitaries, the artificial pomp of aristocratic existence; he brought into his work the entire humanity of his country in a reality that escapes from the noble requirements of traditional Japanese painting. He was passionate about his art, to the point of madness, and sometimes signed his productions, “the drawing madman”.

However, this painter – outside of the cult status given to him by his students – was considered by his contemporaries to be an entertainer for the masses, a low artist of works not worthy of being seen by serious men of taste in the empire of the rising sun. Hokusai did not receive from the public the veneration accorded to the great painters of Japan, because he devoted himself to representing “common life”, but since he had inherited the artistic schools of Kanō and Tosa, he certainly surpassed the Okiyo and the Bunchō. Ironically, it was the fact that Hokusai was one of the most original artists that prevented him from enjoying the glory he merited during his life.

Collection of Surimonos Illustrating Fantastic Poems, c. 1794–1796.

Surimono, nishiki-e, 21.9 × 16 cm.

Pulverer Collection, Cologne.

An Oiran and her Two Shinzō Admiring the Cherry Trees in Bloom in Nakanochō, c. 1796–1800.

Surimono, nishiki-e and dry stamp, 47.8 × 65 cm.

Musée national des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, Paris.

He used his painting and drawing talents in the most varied of domains. Let’s listen to the artist: “After having studied the painting from the various schools for a long time, I penetrated their secrets and I took away the best parts of each. Nothing is unfamiliar to me in painting. I tried my brush at everything I happened upon and succeeded.” In fact, Hokusai painted everything from his most common images, called Kamban, which is to say “image ads”, for travelling theatre companies all the way up to the most sophisticated compositions.

At first, Hokusai was often both the illustrator and the writer of the novel he was publishing. His literature is appreciated for his intimate observations of Japanese life. It is even sometimes attributed, as was his first novel, to the well-known novelist, Kioden. The painter’s literature also has other merits: the mocking spirit of the artist made him a parodist of the literature of his contemporaries, of their style, of their conduct, and above all, of the accumulation of affairs and of the historical jumble. This double role of writer and sketch artist only lasted until 1804, when he devoted himself exclusively to painting.

During the Kansei era (1789–1800), Hokusai wrote many stories and novels for women and children, novels for which he did his own illustrations, novels that he signed as the author Tokitaro-Kakâ and, as the painter Gwakiôjin-Hokusai. It was thanks to his spiritual and precise brushstrokes that the popular stories and novels began to become known to the public. He was also an excellent poet of haïku (popular poetry). Not having had enough time to transmit all of his painting methods to his students, he engraved them into volumes that, later, would be highly successful. During the Tempō era (1830–43), Hokusai published an immense number of nishiki-e, colour prints and drawings of love or obscene images, called shunga, with admirable shading, that he always signed with the pseudonym Gummatei.

He was also highly skilled in the painting called kioku-ye, fantasy painting, done with objects or tableware dipped in India ink, such as boxes used as measuring cups, eggs, or bottles. He also painted admirably well with his left hand, or even from bottom to top. His painting done with his fingernails is especially surprising and if one did not see the artist at work, one would think that his paintings done with fingernails were done with brushes.

His work had the good fortune not only of exciting the admiration of his fellow painters, but also of attracting the masses because of its special novelty. His productions were highly sought after by foreigners and there was even a year in which his drawings and woodcuts were exported by the hundreds, but almost as suddenly, the Tokugawa government banned this export.

Two Women Puppeteers, c. 1795.

Surimono, nishiki-e.

Private collection, United Kingdom.

Tarō Moon, 1797–1798.

Nishiki-e, 22.7 × 16.5 cm.

The British Museum, London.

An anecdote attests to this fame. In fact, at the end of the eighteenth century, Hokusai’s talent not only made him popular with his compatriots, but he was also appreciated by the Dutch. One of them, believed to be Captain Isbert Hemmel, had the intelligent idea of bringing back to Europe two scrolls done by the illustrious master’s brush. They represent, in the first, all the stages in the life of a Japanese man from birth to death, and in the second, all the stages in the life of a Japanese woman, also from birth to death. Hokusai received, from a Dutch doctor, an order for two scrolls and for two more for the captain. The price, agreed upon between the buyers and the artist, was 150 rios in gold (the gold rio being worth one pound sterling). Hokusai brought all his care and technical knowledge to the creation of these four scrolls. They were completed by the time of departure of the Dutchmen. When he delivered the scrolls, the captain, enchanted, gave him the agreed price, but the doctor, on the pretext that he was not treated as well as the captain, only wanted to pay half of the price. Hokusai refused to accept this. However, the sum that the painter should have earned was already slated to pay off some debts and Hokusai’s wife scolded him for not having given one scroll to the doctor, since that sum would have saved them from deep poverty. Hokusai let his wife speak, and, after a long silence, told her that he had no illusions about the poverty that awaited them, but he would not stand for the greed of a stranger who treated them with so little respect, adding: “I prefer poverty to having someone walk all over me.” The captain, when he heard of the doctor’s behaviour, sent his interpreter with the money and bought the two scrolls ordered by the doctor. Hokusai continued to sell some of his drawings to the Dutch, until he was banned from selling details of the intimate lives of the Japanese people to foreigners.

The 300 rios in gold paid to Hokusai by Dutch Captain Isbert Hemmel, for the four makimonos on Japanese life, were certainly the largest payment the painter had ever obtained for his works. In fact, his book illustrations – the artist’s principal revenue – were poorly remunerated by editors, even at the time when the artist enjoyed his greatest celebrity. One can take as evidence this fragment from a letter sent from Uraga in 1836 to the editor, Kobayashi: “I am sending you three and a half pages of ‘Poetry of the Tang Epoch’. Of the forty-two mommes (one rio = 60 mommes) that I have earned, keep one and a half mommes that I owe you; please give the rest, forty and one half mommes to the courier.”

This story also shows the great poverty in which the artist lived, even into his old age. Thus, we also know that Hokusai borrowed miserable sums to pay for his daily needs from fruit sellers and fishmongers. Also, a request the painter made of an editor to borrow one rio, pleading with him to pay this meagre amount in the smallest change possible in order to pay his petty debts to his neighbourhood merchants. Also attesting to this poverty is another letter in which Hokusai complains of having only one robe to keep his seventy-six-year-old body warm during a harsh winter. The artist lived all his life in deep poverty because of the low prices paid in Japan by editors to artists, because of his independent spirit, in the name of which he would only accept work that he liked, and also because of the debts that he had to pay for his son, Tominosuke, and his grandson, by his daughter Omiyo. Moreover, he had a certain vanity about his poverty.

Women on the Beach at Enoshima (Enoshima shunbō), excerpt from the series The Silky Branches of the Willow (Yanagi no ito), 1797.

Nishiki-e, 25.4 × 38 cm.

The British Museum, London.

In 1834, Hokusai sent the following letter to his three editors, Kobayashi, Hanabusa, and Kakumaruya: “As I am travelling, I do not have the time to write to you individually, and am sending to the three of you this one letter that I hope you will all read in turn. I do not doubt that you would like to grant an old man the requests that he makes of you, and I hope that your families are all doing well. As for your old man, he is still the same, the strength of his brush continues to build, and to, more than ever, exercise care. When he is one hundred years old, he will become one of the true artists.” The old painter signed at length, “old Hokusai, the crazy old artist, the beggar priest,” but his letter is, in so many words, entirely in this postscript: “For the book of ‘Warriors’ [undoubtedly Ehon Sakigake, ‘The Heroes of China and Japan‘, printed and engraved by Yegawa], I hope that the three of you will give it to Yegawa Tomekiti. As for the price, arrange that directly with him. The reason I am adamant that the woodcuts be by Yegawa is that, while both the Hokusai Manga and the ‘Poetry’ are certainly two well-engraved works, they are far from the perfection of the three volumes of ‘Mount Fuji’ that he engraved. Now, if my drawings are cut by a good engraver, that will encourage me to work, and if the book is a success, that is also to our advantage because it will bring you greater profit. Because I recommend Yegawa to you so highly, do not think that it is to earn a commission: what I seek is clean execution, and that would be a satisfaction you could give to a poor old man who has not much farther to go (here the painter drew himself, as an old man walking supported by two brushes instead of crutches). As for ‘The Life of Çakyamouni’ (Shakuson Ilidaïki Zuye, an illustrated novel published in 1839), Souzanbô promised me to have it engraved by Yegawa, and I drew it based on this choice: the curly hair of the Indians being very difficult to engrave, even the forms of the bodies, and there is absolutely no one but Yegawa who can execute this work. Hanabusa, after his visit some time ago, told me, when he ordered the ‘Warriors’ from me, that he would not leave me unoccupied and I remind him of his good word. You ordered from my daughter an illustration of the ‘Hundred Poets’, but I would rather illustrate this book, which I will undertake myself after having finished the ‘Warriors’. As for the price, we will come to an agreement, as for a poet. But however, can we agree in advance that it will be Yegawa who will engrave the book?” The letter ends with a sketch in which he salutes his editors.

Village near a Bridge, excerpt from the series “Ritual Dances for Boys” (Otoko Tōka), 1798.

Nishiki-e, 20.6 × 36 cm.

Musée national des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, Paris.

Act I, excerpt from the illustrated book Chūshingura, c. 1798.

Nishiki-e, 22 × 32.7 cm.

The British Museum, London.

Dawn of a New Year, 1798.

Nishiki-e, 22.5 × 16.3 cm.

The British Museum, London.

Another letter from Hokusai was sent to editor Kobayashi, dated 1835: “I did not ask about you, but I am happy to know that you are in good health. As for myself, I saw the delinquent, the incorrigible who will always fall back on me. Since then, I have had to ask for the advice of friends and family. Finally, I found a respondent (someone who would take responsibility for watching over him). We will make him manage a fish store, and we have also found him a wife who will arrive here in two or three days. But all that is still at my expense. It is due to these obstacles that I am behind in illustrating the Suïkoden and Toshisen (Tang poetry), for which I have only started the sketches. I will, however, send you some drawings and in that case, I am counting on…” Here, the painter drew a hand holding a silver coin.

Another letter, undated, was sent to the editor, Kobayashi: “With the clear tones of India ink, I delete all the vignetting. Since, while done all by itself with the tip of the brush, for the painter, the worker printing the plates could at least make 200 vignetted copies: beyond that number is impossible. For the light ink tone, make it as light as possible: the trend towards dark tones makes the print hard on the eyes. Tell the worker that the light ink tone should be the same as that of scallop soup, which is to say very light; now, for the medium ink tone, if it is printed too lightly, it will take away the power of the tint, and you need to tell the print worker that the medium tint must have a thick texture, somewhat like bean soup. In any case, I will examine the proofs, but at present, I recommend these details because I want to have my drawings cooked well.”

Artisan’s Workshop near Mount Fuji, 1798.

Nishiki-e, 22 × 31.2 cm.

Private collection.

A last letter by Hokusai, written at the beginning of the year, 1836, was sent to the editor Kobayashi from Uraga. This letter, written about New Year’s Day, has, as a header, a sketch in which the painter, in official garb, between two fir branches, is taking a deep bow. “There are several doors at which I must express my wishes for the New Year, so I will return another day, and goodbye, goodbye… But, until then, concerning the drawings to be engraved, please discuss the details with Yegawa. However, a bit later you will find a recommendation for the other woodcutters. Thank you for your frequent loans. I think that by the beginning of the second month of the year, I will have used up the paper, the colours, the brushes, and that I will be forced to go to Edo, in person, so I will visit you secretly and give you, orally, all the details that you may need. In this harsh season, above all during my travels, all things are very difficult, and among others, living in this severe cold with one lone robe, at the age of seventy-six. I ask you to think of the sad conditions in which I find myself, but my arm (here a sketch of his arm) has not weakened the least, and I work with determination. My only pleasure is becoming a good artist.” Atthe end of the letter, he represents himself in a microscopic sketch, humbly saluting between his hat and his drawing set on the ground. Hokusai loved postscripts, and so his letter continues: “I recommend that the engraver not add the lower eyelid when I do not draw it; for the noses, these two noses are mine (here a drawing of a nose in profile and from the front) and those that one is accustomed to engraving are Utagawa’s noses, which I do not like at all and counter the rules of drawing. It is also fashionable to draw eyes this way (here, drawings of eyes with a black dot in the centre), but I do not like these eyes any more than the noses.” Hokusai ended his letter with this sentence: “As my life, at this moment, is not public, I will not give you my address here.”

Chinese Goddess Taichen Wang Furen and a Dragon with Qin, 1798.

Diptych, ink, colour and gofun on paper, each sheet: 125.4 × 56.5 cm.

Private collection.

Finally, in a letter from 1842, sent to editors Hanabusa Keikiti and Hanabuza Bunzô after his return to Edo, he remained in hiding: “A thousand thanks for your latest friendly visit and also for not abandoning an old man, and yet again for your nice New Year’s gift. Since last spring, my prodigal grandson has behaved deplorably; I have had, every day, to occupy myself with cleaning up the results of his filthy life, and I am at the point of sending him away. But he has found, as always, characters much too indulgent who have made me wait until the day he commits a new, more serious error. However, at the beginning of this year, I had to have his father Yanagawa Shighenobu take him to the Montzu province (a northern province), but he is easily capable of escaping along the way. Until then, I can breathe a little. Here are the reasons that have kept me from coming to thank you for the book by Soga Monogatari (an old book loaned to him). This New Year, I had neither money, nor clothing, and I am only able to feed myself poorly and not seeing my real New Year start until the middle of its second month. In the second month of last year, when Yeibun came to see me, I had already finished two volumes of Suiko (ninety-volume novel started in 1807), but I have not been able to advance any further. In sum, I lost an entire year because of my mischievous grandson and I regret this precious year lost. I have kept your Soga Monogatari for a long time, but I hope that you can leave it with me until the second month when I will come visit you. Another recommendation, send me, as soon as possible, the silk for painting the goddess Daghiniten (the goddess represented mounted on a fox), because time passes as quickly as an arrow and you had asked me to deliver this painting to you in the second month. If the text of Gaden is ready, send it to me when you send me the silk, also send the price for the illustration of the two volumes of Gaden. When you come, do not ask for Hokusai, no one will know how to answer you, ask for the priest who draws and who recently moved into the building owned by Gorobei in the courtyard of the Mei-ô-in Temple, in the middle of the woods (small forest of Asakusa).”

As capricious as all the great artists, Hokusai was not always in good humour and took a malicious pleasure in being disagreeable towards people who did not show him the deference he thought was due to him or who were, quite simply, unpleasant, as these anecdotes show.

Onoye Baïkô, a great actor of the time, recognised Hokusai’s very particular talent for inventing ghosts, and asked the painter to use his imagination to draw a being from another world to serve as a representation of a character on a theatrical set. The actor invited the painter to come see him, which Hokusai avoided doing. The actor then decided to visit him. He found the workshop so dirty that he did not dare sit on the ground. He had his travelling blanket brought, upon which he greeted Hokusai. The painter, offended, did not turn around, continuing to paint and the illustrious Baïkô, unhappy, left. But he wanted his drawing so much that he had the ‘weakness’ to excuse himself to Hokusai to obtain it. At the same time, Hokusai received a visit from a supplier to the shogun, who came to ask him for a drawing. It is not clear what displeased Hokusai, but we do know, however, that the painter took some lice from his robe and roughly threw them on the visitor, saying that because he was very busy, he was not available. The visitor resigned himself to waiting and obtained the drawing he wanted. But this latter had barely left when Hokusai, running after him, yelled at him in a jeering voice: “Do not forget, if people ask you how my studio is, to tell them that it is very beautiful! Very clean!”

The same fantasy is expressed in his work. In 1804, Hokusai completed, in the form of a public improvisation, a large format painting of a Darma. This event made great waves, and piqued the curiosity of the Tokugawa shogun, who had wanted to see the master work, even though under the Tokugawa, and to this day, no commoner could present himself before the shogun. Thus, one autumn day, upon returning from a hunt with his falcon, the shogun had Hokusai summoned and entertained himself by watching the painter execute his drawings. Suddenly, Hokusai, covering half of an immense piece of paper with indigo, made roosters, after plunging their feet into purple ink, run across it. The prince, surprised, had the illusion of seeing the Tatsuta River with its rapids sweeping up purple momiji leaves in its waters.

Women with a Telescope, excerpt from the series The Seven Bad Habits (Fūryū nakute nana kuse), late 1790s.

Ōban, nishiki-e.

Kobe City Museum, Kobe.

Young Woman Applying Makeup seen from behind; above, a Poem in Chinese by Santō Kyōden, c. 1800.

Paint on paper, 132.9 × 49.4 cm.

Ōta Memorial Museum, Tokyo.

Young Dandy, c. 1800–1801.

Coloured ink on silk, 33.9 × 20.3 cm.

Rikardson-Kawano Collection, Tokyo.

In 1817, during one of Hokusai’s trips to Nagoya, the painter received an order for many book illustrations. Since his students vaunted the accuracy of representation of the beings and things in his drawings, particularly those in small formats, critics of ‘vulgar painting’ retorted that the little things produced by Hokusai’s brush were crafts and not art. These words hurt Hokusai and led him to say that, if a painter’s talent consisted in the size of the dimensions of his strokes and his works, he was ready to surprise his critics. This was when his student, Bokusen, and his friends came to help him execute, in public, a tremendous painting, a Darma of very different proportions than the one he painted in 1804. It was completed on the fifth day of the tenth month of the year, in front of the temple of Nishig-hakejo. The Japanese biography of Hokusai tells about this, from a story in drawings by Yenko-an, a friend of the painter.

In the middle of the north courtyard of the temple, protected by a fence, was spread a paper, specially made several times thicker than ordinary paper. On this piece of paper, Hokusai would paint a surface equivalent to that of 120 mats. Knowing that a Japanese mat measures 90 cm wide by 180 cm tall, this gave the artist a painting area 194 m long! To keep the paper stretched out, a very thick bed of rice straw was made, and at points, pieces of wood were set, serving as weights to keep the wind from lifting the paper. A scaffold was set up against the council chamber, facing the public. At the top of the scaffold, pulleys were attached to ropes in order to lift the immense drawing, fixed to a gigantic wood beam. Large brushes had been prepared, the smallest being the width of a broom. India ink was stored in enormous vats, to then be poured into a cask. These preparations occupied the entire morning, and from the first light of day, a crowd of nobles, yokels, women, old men, and children gathered in the temple courtyard to see the drawing produced.

In the afternoon, Hokusai and his students, in almost ceremonial garb, with bare legs and arms, got to work, students carrying ink in the cask, putting it into a bronze basin and accompanying the painter at work moving across the giant page. Hokusai first took a brush the width of a sheaf of hay. After dipping it in the ink, he drew the nose, and then the left eye of the Darma. He took several strides and drew the mouth and the ear. Then, he ran, tracing the outline of the head. That done, he completed the hair and the beard, taking, to shade them, another brush made strands of coconut that he dipped in a lighter India ink. At that moment, his students brought, on an immense platter, a brush made of rice sacks soaked in ink. To this brush was attached a rope. The brush was placed at a place indicated by Hokusai. He attached the rope around his neck and pulled the brush, with small steps, to make the thick lines of the Darma’s robe. When the lines were complete, he had to colour the robe red. Some students took that colour in buckets and spread it with shovels, while others mopped up the excess colour with wet towels. It was not until dusk that the Darma was completed. It was lifted up with the pulleys, but part of the paper stayed in the middle of the crowd, who, as in the Japanese expression, resembled an “army of ants around a piece of cake”. It was not until the next day that they were able to extend the scaffold sufficiently to lift the entire painting into the air.

This performance made Hokusai’s name burst out like a “thunder clap”. For some time, throughout the city, one saw everywhere, drawn on frames, screens, walls, and even in the sand by children, Darmas, this saint who had been deprived of sleep. According to the legend, indignant at having fallen asleep one night, he cut off his eyelids. He threw them far away, as if they were miserable sinners. By a miracle, his eyelids took root where they had fallen and a tea plant grew, giving the fragrant drink that drives away drowsiness. This was not the only huge painting that Hokusai executed. Later, he painted, in Honjô, a colossal horse. Later still, in Ryōgoku, he completed a giant hotel, that he signed, “Kintaïsga Hokusai”: “Hokusai of the house of the brocade sack”, alluding to the canvas sack carried by the gods. The day he painted the horse the size of an elephant, we are told that he laid his brush on a grain of rice, and when the grain of rice was examined under a magnifying glass, one had the illusion of seeing, in the microscopic stain from the brush, the flight of two sparrows.

The greatest honour that this artist obtained during his life was that his fame reached all the way to the Tokugawa court, and that he was able to display his talent, without rival, before the great prince. Once, while the shogun was walking in the city of Edo, Hokusai was invited by the prince to paint before him. He first started to trace a rooster’s feet on an immense sheet of paper with a brush, then suddenly transforming the drawing by putting a touch of indigo on the feet, he created a landscape of the Tatsuta River that he presented to the surprised prince.

Name and signature changes are typical in the life of a Japanese painter. But with Hokusai, these changes were more frequent than with any other painter from Japan. These name changes all have a history. Thus, at one point, the master handed down his signature of Hokusai to one of his students who owned a restaurant in Yoshiwara, a neighbourhood of public houses. This student painted in his establishment, paintings of 16 ken (32 metres), each time that Hokusai made an overture to the artists’ guilds to adopt a new signature.

The Poet Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, c. 1802.

Ink and colour on silk, 34.8 × 44.3 cm.

Museo d’Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genoa.