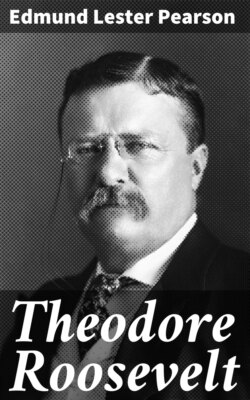

Читать книгу Theodore Roosevelt - Edmund Lester Pearson - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER I

THE BOY WHO COLLECTED ANIMALS

If you had been in New York in 1917 or 1918 you might have seen, walking quickly from a shop or a hotel to an automobile, a thick-set but active and muscular man, wearing a soft black hat and a cape overcoat. Probably there would have been a group of people waiting on the sidewalk, as he came out, for this was Theodore Roosevelt, Ex-President of the United States, and there were more Americans who cared to know what he was doing, and to hear what he was saying, than cared about any other living man.

Although he was then a private citizen, holding no office, he was a leader of his country, which was engaged in the Great War. Americans were being called upon—the younger men to risk their lives in battle, and the older people to suffer and support their losses. Theodore Roosevelt had always said that it was a good citizen’s duty cheerfully to do one or the other of these things in the hour of danger. They knew that he had done both; and so it was to him that men turned, as to a strong and brave man, whose words were simple and noble, and what was more important, whose actions squared with his words.

He had come back, not long before, from one of his hunting trips, and it was said that fever was still troubling him. The people wish to know if this is true, and one of the men on the sidewalk, a reporter, probably, steps forward and asks him a question.

He stops for a moment, and turns toward the man. Not much thought of sickness is left in the mind of any one there! His face is clear, his cheeks ruddy—the face of a man who lives outdoors; and his eyes, light-blue in color, look straight at the questioner. One of his eyes, it had been said, was dimmed or blinded by a blow while boxing, years before, when he was President. But no one can see anything the matter with the eyes; they twinkle in a smile, and as his face puckers up, and his white teeth show for an instant under his light-brown moustache, the group of people all smile, too.

His face is so familiar to them—it is as if they were looking at somebody they knew as well as their own brothers. The newspaper cartoonists had shown it to them for years. No one else smiled like that; no one else spoke so vigorously.

“Never felt better in my life!” he answers, bending toward the man.

“But thank you for asking!” and there is a pleasant and friendly note in his voice, which perhaps surprises some of those who, though they had heard much of his emphatic speech, knew but little of his gentleness. He waves his hand, steps into the automobile, and is gone.

Theodore Roosevelt was born October 27, 1858, in New York City, at 28 East Twentieth Street. The first Roosevelt of his family to come to this country was Klaes Martensen van Roosevelt who came from Holland to what is now New York about 1644. He was a “settler,” and that, says Theodore Roosevelt, remembering the silly claims many people like to make about their long-dead ancestors, is a fine name for an immigrant, who came over in the steerage of a sailing ship in the seventeenth century instead of the steerage of a steamer in the nineteenth century. From that time, for the next seven generations, from father to son, every one of the family was born on Manhattan Island. As New Yorkers say, they were “straight New York.”

Immigrant or settler, or whatever Klaes van Roosevelt may have been, his children and grandchildren had in them more than ordinary ability. They were not content to stand still, but made themselves useful and prosperous, so that the name was known and honored in the city and State even before the birth of the son who was to make it illustrious throughout the world.

“My father,” says the President, “was the best man I ever knew. … He never physically punished me but once, but he was the only man of whom I was ever really afraid.” The elder Roosevelt was a merchant, a man courageous and gentle, fond of horses and country life. He worked hard at his business, for the Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, and for the poor and unfortunate of his own city, so hard that he wore himself out and died at forty-six. The President’s mother was Martha Bulloch from Georgia. Two of her brothers were in the Confederate Navy, so while the Civil War was going on, and Theodore Roosevelt was a little boy, his family like so many other American families, had in it those who wished well for the South, and those who hoped for the success of the North.

Many American Presidents have been poor when they were boys. They have had to work hard, to make a way for themselves, and the same strength and courage with which they did this has later helped to bring them into the White House. It has seemed as if there were magic connected with being born in a log-cabin, or having to work hard to get an education, so that only the boys who did this could become famous. Of course it is what is in the boy himself, together with the effect his life has had on him, that counts. The boy whose family is rich, or even well-off, has something to struggle against, too. For with these it is easy to slip into comfortable and lazy ways, to do nothing because one does not have to do anything. Some men never rise because their early life was too hard; some, because it was too easy.

Roosevelt might have had the latter fate. His father would not have allowed idleness; he did not care about money-making, especially, but he did believe in work, for himself and his children. When the father died, and his son was left with enough money to have lived all his days without doing a stroke of work, he already had too much grit to think of such a life. And he had too much good sense to start out to become a millionaire and to pile million upon useless million.

He had something else to fight against: bad health. He writes: "I was a sickly, delicate boy, suffered much from asthma, and frequently had to be taken away on trips to find a place where I could breathe. One of my memories is of my father walking up and down the room with me in his arms at night, when I was a very small person, and of sitting up in bed gasping, with my father and mother trying to help me. I went very little to school. I never went to the public schools, as my own children later did."[1] For a few months he went to a private school, his aunt taught him at home, and he had tutors there.

[1] “Autobiography.”

When he was ten his parents took him with his brother and sisters for a trip to Europe, where he had a bad time indeed. Like most boys, he cared nothing for picture-galleries and the famous sights, he was homesick and he wished to get back to what really pleased him—that is, collecting animals. He was already interested in that. And only when he could go to a museum and see, as he wrote in his diary, “birds and skeletons” or go “for a spree” with his sister and buy two shillings worth of rock-candy, did he enjoy himself in Europe.

His sister knew what he thought about the things one is supposed to see in Europe, and in her diary set it down:

“I am so glad Mama has let me stay in the butiful hotel parlor while the poor boys have been dragged off to the orful picture galary.”

These experiences are funny enough now, but probably they were tragic to him at the time. In a church in Venice there were at least some moments of happiness. He writes of his sister “Conie”:

“Conie jumped over tombstones spanked me banged Ellies head &c.”

But in Paris the trip becomes too monotonous; and his diary says:

November 26. “I stayed in the house all day, varying the day with brushing my hair, washing my hands and thinking in fact having a verry dull time.”

November 27. “I did the same thing as yesterday.”

They all came back to New York and again he could study and amuse himself with natural history. This study was one of his great pleasures throughout life and when he was a man he knew more about the animals of America than anybody except the great scholars who devoted their lives to this alone.

It started with a dead seal that he happened to find laid out on a slab in a market in Broadway. He was still a small boy, but when he heard that the seal had been killed in the harbor, it reminded him of the adventures he had been reading about in Mayne Reid’s books. He went back to the market, day after day, to look at the seal, to try to measure it and to plan to own it and preserve it. He did get the skull, and with two cousins started what they gave the grand name of the "Roosevelt Museum of Natural History"!

Catching and keeping specimens for this museum gave him more fun than it gave to some of his family. His mother was not well pleased when she found some young white mice in the ice-chest, where the founder of the “Roosevelt Museum” was keeping them safe. She quickly threw them away, and her son, in his indignation, said that what hurt him about it was “the loss to Science! The loss to Science!” Once, he and his cousin had been out in the country, collecting specimens until all their pockets were full. Then two toads came along—such novel and attractive toads that room had to be made for them. Each boy put one toad under his hat, and started down the road. But a lady, a neighbor, met them, and when the boys took off their hats, the toads did what any sensible toads would do, hopped down and away, and so were never added to the Museum.

The Roosevelt family visited Europe again in 1873, and afterwards went to Algiers and Egypt, where the air, it was hoped, would help the boy’s asthma. This was a pleasanter trip for him, and the birds which he saw on the Nile interested him greatly.

His studies of natural history had been carried on in the summers at Oyster Bay on Long Island, on the Hudson and in the Adirondacks. They soon became more than a boy’s fun, and some of the observations made when he was fifteen, sixteen or seventeen years old have found their way into learned books. When the State of New York published, many years afterwards, two big volumes about the birds of the state, some of these early writings by Roosevelt were quoted as important. A friend has given me a four-page folder printed in 1877, about the summer birds of the Adirondacks “by Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., and H. D. Minot.” Part of the observations were made in 1874 when he was sixteen. Ninety-seven different birds are listed.

When he was fifteen and had returned a second time from Europe, he began to study to enter Harvard. He was ahead of most boys of his age in science, history and geography and knew something of German and French. But he was weak in Latin, Greek and mathematics. He loved the out-of-doors side of natural history, and hoped he might be a scientist like Audubon.

CHAPTER II

IN COLLEGE

Roosevelt entered the Freshman class of Harvard University in 1876. It is worth while to remember that this man who became as much of a Westerner as an Easterner, who was understood and trusted by the people of the Western States, was born on the Atlantic coast and educated at a New England college.

The real American, if he was born in the East, does not talk with contempt about the West; if he is a Westerner he does not pretend that all the good in the world is on his side of the Mississippi. Nor, wherever he came from, does he try to keep up old quarrels between North and South. Theodore Roosevelt was an American, and admired by Americans everywhere. Foolish folk who talk about the “effete East,” meaning that the East is worn out and corrupt, had best remember that Abraham Lincoln did not believe that when he sent his son to the same college which Theodore Roosevelt’s father chose for him.

At Harvard he kept up his studies and interest in natural history. In the house where he lived he sometimes had a large, live turtle and two or three kinds of snakes. He went in to Boston and came back with a basket full of live lobsters, to the consternation of the other people in the horse-car. He held a high office in the Natural History Society, and took honors, when he graduated, in the subject. His father had encouraged his desire to be a professor of natural history, reminding him, however, that he must have no hopes of being a rich man. In the end he gave up this plan, not because it did not lead to money, for never in his life did he work to become wealthy, but because he disliked science as it was then taught. One of the bad things the German universities had done to the American colleges was to make them worship fussy detail, and so science had become a matter of microscopes and laboratories. The field-work of the naturalist was unknown or despised.

He took part in four or five kinds of athletics. He seems never to have played baseball, perhaps because of poor eyesight which made him wear glasses. But he practiced with a rifle, rowed and boxed, ran and wrestled. In his vacations he went hunting in Maine. Boxing was one of his favorite forms of sport—for two reasons. He thought a boy or a man ought to be able to defend himself and others, and he enjoyed hard exercise.

It is important to know what he thought and did about self-defense and fighting. Many people dodge this, and other difficult subjects, when they are talking to boys. It was not Roosevelt’s way to hide his thoughts in silence because of timidity, and then call his lack of action by some such fine name as “tact” or “discretion.” When there was good reason for speaking out he always did so. Since a boy who is forever fighting is not only a nuisance, but usually a bully, some older folk go to the extreme and tell boys that all fighting is wrong.

Theodore Roosevelt did not believe it. When he was about fourteen, and riding in a stage-coach on the way to Moosehead Lake, two other boys in the coach began tormenting him. When he tried to fight them off, he found himself helpless. Either of them could handle him, could hit him and prevent him from hitting back. He decided that it was a matter of self-respect for a boy to know how to protect himself and he learned to box.

Speaking to boys he said later:

“One prime reason for abhorring cowards is because every good boy should have it in him to thrash the objectionable boy as the need arises.”

And again:

“The very fact that the boy should be manly and able to hold his own, that he should be ashamed to submit to bullying, without instant retaliation, should in return, make him abhor any form of bullying, cruelty, or brutality.”[2]

[2] These two quotations from essay called “The American Boy” in “The Strenuous Life,” pp. 162, 164

When he was teaching a Sunday School class in Cambridge, during his time at college, one of his pupils came in with a black eye. It turned out that another boy had teased and pinched the first boy’s sister during church. Afterwards there had been a fight, and the one who tormented the little girl had been beaten, but he had given the brother a black eye.

“You did quite right,” said Roosevelt to the brother and gave him a dollar.

But the deacons of the church did not approve, and Roosevelt soon went to another church.

Meanwhile he was learning to box. In his own story of his life he makes fun of himself as a boxer, and says that in a boxing match he once won “a pewter mug” worth about fifty cents. He is honest enough to say that he was proud of it at the time, “kept it, and alluded to it, and I fear bragged about it, for a number of years, and I only wish I knew where it was now.”

His college friends tell a different story of him. He was never one of the best boxers, they say, and he was at a disadvantage because of his eyesight. But he was plucky enough for two, and he fought fair. He entered in the lightweight class in the Harvard Gymnasium, March 22, 1879. He won the first match. When time was called he dropped his hands, and his opponent gave him a hard blow on the face. The fellows around the ring all shouted “Foul! Foul!” and hissed. But Roosevelt turned toward them, calling “Hush! He didn’t hear!”

In the second match he met a man named Charlie Hanks, who was a little taller, and had a longer reach, and so for all Roosevelt’s pluck and willingness to take punishment, Hanks won the match.

He was a member of three or four clubs—the Institute, the Hasty Pudding and the Porcellian. He was one of the editors of the Harvard Advocate, took part in three or four college activities, and was fond of target shooting and dancing. It is told that he never spoke in public, until about his third year in college, that he was shy and had great difficulty in speaking. It was by effort that he became one of the best orators of his day.

Roosevelt did not like the way college debates were conducted. He said that to make one side defend or attack a certain subject, without regard to whether they thought it right or wrong, had a bad effect.

“What we need,” he wrote, “is to turn out of colleges young men with ardent convictions on the side of right; not young men who can make a good argument for either right or wrong, as their interest bids them.”

He did one thing in college which is not a matter of course with students under twenty-two years old. He began to write a history, named “The Naval War of 1812.” It was finished and published two years after he graduated, and in it he showed that his idea of patriotism included telling the truth. Most American boys used to be brought up on the story of the American frigate Constitution whipping all the British ships she met, and with the notion that the War of 1812 was nothing but a series of brilliant victories for us.

Theodore Roosevelt thought that Americans were not so soft that they were afraid to hear the truth, and that it was a poor sort of American who dared not point out to his fellow-countrymen the mistakes they had made and the disasters which followed. It did not seem patriotic to him to dodge the fact that lack of wisdom at Washington had let our Army run down before the war, so that our attempts to invade Canada were failures, and that we suffered the disgrace of having Washington itself captured and burned by the enemy.

There was a great deal to be proud of in what our Navy did, and in the Army’s victory in the Battle of New Orleans, and these things Roosevelt described with the pride of every good American. But he had no use for the old-fashioned kind of history, which pretends that all the bravery is on one side. He did his best to get at the truth, and he knew that the English and Canadians had fought bravely and well, and so he said just that. Where our troops or our ships failed it was not through lack of courage, but because they were badly led, and what was worse, since it was so unnecessary, because the Government at Washington had lost the battle in advance by neglecting to prepare.

Before he was twenty-four, Roosevelt was so well-informed in the history of this period that he was later asked to write the chapter dealing with the War of 1812 in a history of the British Navy.

At his graduation from Harvard he stood twenty-second in a class of one hundred and seventy. This caused him to be elected to the Phi Beta Kappa, the society of scholars. Before he graduated he became engaged to be married to Miss Alice Lee of Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts.

He told his friend, Mr. Thayer, what he was going to do after graduation.

“I am going to try to help the cause of better government in New York City,” he said. And he added:

“I don’t know exactly how.”

CHAPTER III

IN POLITICS

When he graduated from college Roosevelt was no longer in poor health. His boxing and exercise in the gymnasium, and still more his outdoor expeditions, and hunting trips in Maine, had made a well man of him. He was yet to achieve strength and muscle, and his life in the West was to give him the chance to do that.

His father died while he was in college and he was left, not rich, but so well off that he might have lived merely amusing himself. He might have spent his days in playing polo, hunting and collecting specimens of animals. What he did during his life, in adding to men’s knowledge of the habits of animals, would have gained him an honorable place in the history of American science, if he had done nothing else. So with his writing of books. He earned the respect of literary men, and left a longer list of books to his credit than do most authors, and on a greater variety of subjects. But he was to do other and still more important work than either of these things.

He believed in and quoted from one of the noblest poems ever written by any man—Tennyson’s “Ulysses.” And in this poem are lines which formed the text for Roosevelt’s life:

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnish’d, not to shine in use!

As tho' to breathe were life.

This was the doctrine of “the strenuous life” which he preached—and practiced. It was to perform the hard necessary work of the world, not to sit back and criticize. It was to do disagreeable work if it had to be done, not to pick out the soft jobs. It was to be afraid neither of the man who fights with his fists or with a rifle, nor of the man who fights with a sneering tongue or a sarcastic pen.

To go into New York politics from 1880–1882 was, for a young man of Roosevelt’s place in life, just out of college, what most of his friends and associates called “simply crazy.” That young men of good education no longer think it a crazy thing to do, but an honorable and important one, is due to Theodore Roosevelt more than to any other one man.

As he sat on the window-seat of his friend’s room in Holworthy Hall, that day, and said he was going to try to help the cause of better government in New York, Mr. Thayer looked at him and wondered if he were “the real thing.” Thirty-nine years later Mr. Thayer looked back over the career of his college mate, and knew that he had talked that day with one of the great men of our Republic, with one who, as another of his college friends says, was never a “politician” in the bad sense, but was always trying to advance the cause of better government.

The reason why it seemed to many good people a crazy thing to go into politics was that the work was hard and disagreeable much of the time. Politics were in the hands of saloon-keepers, toughs, drivers of street cars and other “low” people, as they put it. The nice folk liked to sit at home, sigh, and say: “Politics are rotten.” Then they wondered why politics did not instantly become pure. They demanded “reform” in politics, as Roosevelt said, as if reform were something which could be handed round like slices of cake. Their way of getting reform, if they tried any way at all, was to write letters to the newspapers, complaining about the “crooked politicians,” and they always chose the newspapers which those politicians never read and cared nothing about.

If any decent man did go into politics, hoping to do some good, these same critics lamented loudly, and presently announced their belief that he, too, had become crooked. If it were said that he had been seen with a politician they disliked, or that he ate a meal in company with one, they were sure he had gone wrong. They seemed to think that a reformer could go among other officeholders and do great work, if he would only begin by cutting all his associates dead, and refusing to speak to them.

It was a fortunate day for America when Theodore Roosevelt joined the Twenty-first District Republican Club, and later when he ran for the New York State Assembly from the same district. He was elected in November, 1881. This was his beginning in politics.

In the Assembly at Albany, he presently made discoveries. He learned something about the crooked politicians whom the stay-at-home reformers had denounced from afar. He found that the Assembly had in it many good men, a larger number who were neither good nor bad, but went one way or another just as things happened to influence them at the moment. Finally, there were some bad men indeed. He found that the bad men were not always the poor, the uneducated, the men who had been brought up in rough homes, lacking in refinement. On the contrary, he found some extremely honest and useful men who had had exactly such unfavorable beginnings.

Also, he soon discovered that there were, in and out of politics, some men of wealth, of education, men who boasted that they belonged to the “best families,” who were willing to be crooked, or to profit from other men’s crooked actions. He soon announced this discovery, which naturally made such men furious with him. They pursued him with their hatred all his life. Some people really think that great wealth makes crime respectable, and if it is pointed out to a wealthy but dishonest man, that he is merely a common thief, and if in addition, the fact is proved to everybody’s satisfaction, his anger is noticeable.

Along with his serious work in the Assembly, Roosevelt found that there was a great deal of fun in listening to the debates on the floor, or the hearings in committees. One story, which he tells, is of two Irish Assemblymen, both of whom wished to be leader of the minority. One, he calls the “Colonel,” the other, the “Judge.” There was a question being discussed of money for the Catholic Protectory, and somebody said that the bill was “unconstitutional.” Mr. Roosevelt writes:

The Judge, who knew nothing—of the constitution, except that it was continually being quoted against all of his favorite projects, fidgetted about for some time, and at last jumped up to know if he might ask the gentleman a question. The latter said “Yes,” and the Judge went on, “I’d like to know if the gintleman has ever personally seen the Catholic Protectoree?” “No, I haven’t,” said his astonished opponent. “Then, phwat do you mane by talking about its being unconstitootional? It’s no more unconstitootional than you are!” Then turning to the house with slow and withering sarcasm, he added, “The throuble wid the gintleman is that he okkipies what lawyers would call a kind of a quasi-position upon this bill,” and sat down amid the applause of his followers.

His rival, the Colonel, felt he had gained altogether too much glory from the encounter, and after the nonplussed countryman had taken his seat, he stalked solemnly over to the desk of the elated Judge, looked at him majestically for a moment, and said, “You’ll excuse my mentioning, sorr, that the gintleman who has just sat down knows more law in a wake than you do in a month; and more than that, Mike Shaunnessy, phwat do you mane by quotin' Latin on the flure of this House, when you don’t know the alpha and omayga of the language!” and back he walked, leaving the Judge in humiliated submission behind him. [3]

[3] “American Ideals,” p. 93.

Another story also relates to the “Colonel.” He was presiding at a committee meeting, in an extremely dignified and severe state of mind. He usually came to the meetings in this mood, as a result of having visited the bar, and taken a number of rye whiskies. The meeting was addressed by “a great, burly man … who bellowed as if he had been a bull of Bashan.”

The Colonel, by this time pretty far gone, eyed him malevolently, swaying to and fro in his chair. However, the first effect of the fellow’s oratory was soothing rather than otherwise, and produced the unexpected result of sending the chairman fast asleep bolt upright. But in a minute or two, as the man warmed up to his work, he gave a peculiar resonant howl which waked the Colonel up. The latter came to himself with a jerk, looked fixedly at the audience, caught sight of the speaker, remembered having seen him before, forgot that he had been asleep, and concluded that it must have been on some previous day. Hammer, hammer, hammer, went the gavel, and—

“I’ve seen you before, sir!”

“You have not,” said the man.

“Don’t tell me I lie, sir!” responded the Colonel, with sudden ferocity. “You’ve addressed this committee on a previous day!”

“I’ve never—” began the man; but the Colonel broke in again:

“Sit down, sir! The dignity of the chair must be preserved! No man shall speak to this committee twice. The committee stands adjourned.” And with that he stalked majestically out of the room, leaving the committee and the delegation to gaze sheepishly into each other’s faces. [4]

[4] “American Ideals,” p. 96.

There was in the Assembly a man whom Mr. Roosevelt calls “Brogan.”