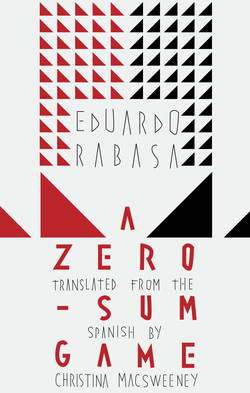

Читать книгу A Zero-Sum Game - Eduardo Rabasa - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI

1

All I ever wanted was to be just another invisible coward, Max Michels silently grumbled as a drop of blood dribbled down his freshly shaved throat. Almost unconsciously, he’d put off until the very last moment the decision that, once taken, seemed as surprising as it was irrevocable. He was about to break the cardinal rule of Villa Miserias: to stand as a candidate in the elections for the president of the residents’ association without the consent of Selon Perdumes.

With the force of a rusty spring unexpectedly uncoiling, the memory of an era before Perdumes’ arrival materialized in his mind. Max clearly recalled the principal feature of the day the modernization began: jubilation at the sight of the dust. There was no lack of people who gladly inhaled the first particles of the future. Poor devils, Max now thought. The dust had never cleared: Villa Miserias was a perpetual work in progress.

At that time the residential estate had functioned like clockwork; it still did, although the model was now completely different. Every two years there were elections for the presidency of the estate’s board. For eleven days, the residents were bombarded with election leaflets. The most distinguished ladies received chocolates and flowers; those of lower standing had to make do with bags of rice and dried beans. In essence, all the candidates were competing to convince the voters they were the one who would make absolutely no alterations to the established order. There was even a physical prototype for those in charge of running the estate that included, in equal measure, the fat, the short, the dark, and bald: it was a bearing, a gaze, a malleable voice. There was no friction between the election manifestos and the everyday state of affairs.

The foundations of Villa Miserias were conceived on the same basis as Selon Perdumes’ fundamental doctrine: Quietism in Motion. Its forty-nine buildings were constructed using an engineering technique designed to allow shaking while avoiding collapse. The smear of city to which it belonged was prone to lethal earthquakes, but the flexible structure of the buildings had prevented catastrophe on more than one occasion.

In the time before the reforms all the apartments had been identical; now they were symmetrically unequal. Each building had ten in total, distributed in inverse proportion to the corresponding floor. In general, the demography was also predictable: in the tiny apartments on the lowest floor, multiple generations of humans and animals lived together. In contrast, the penthouse apartments were usually inhabited by young executives with or without wives and children. In exchange for their privileged position, they had to endure the swaying motion of the building, some of which was caused by the passage of buses on the broad road surrounding the estate. One such resident, who had a panoramic view of the earthquake that reduced the neighboring estate to rubble, defined the spectacle as a waltz danced by flexible concrete colossi.

Perdumes delighted in the improbable equilibrium of successful social engineering. His conversion into Villa Miserias’ foremost resident was a gradual process. He’d arrived on the estate as a businessman of mysterious origins and activities. Each person who spoke to him received an explanation as vague as it was different to the others. To give a clearer idea of his character, one only has to say that—so far—it’s reasonable to imagine they were all true.

He moved into apartment 4B in Building 10, having offered its owner, the widow Inocencia Roca, a year’s rent in advance in exchange for a substantial discount. The inhabitants of Villa Miserias—accustomed to the traditional barter system—weren’t prepared for the way Selon Perdumes flashed the greenbacks. Señora Roca was unaware that she would soon be signing over the apartment to him.

Sightings of him were rare: he kept them to the bare minimum. In order to introduce himself to his neighbors, he invited them individually for coffee. He was charming in the most chameleonic sense of the term. His eyes were the shade of gray that can be taken as either blue or green. He was able to guess the most deeply hidden fears of each of his guests and had an amazing talent for giving solidity to fantasies, then offering the finance needed to make them real. The calculated non-payment of a proportion of his creditors was, for him, a great blessing since he practiced a different sort of usury. In exchange for the possibility of being ruined, he sought to acquire loyalties and secrets. Like an expert dentist who extracts a molar without his anaesthetized patient being aware, his magnetism attracted confessions that enabled him to understand people via their weaknesses.

The young couple in 4A became the subjects of one of his first laboratory experiments. After an informal chat, Perdumes noted the tensions inherent in their different origins. The young man had followed in his father’s footsteps to become a public accountant; she’d studied literature in a state university thanks to the family Popsicle business. He’d been stagnating in an accountancy firm for two years; she worked as the assistant of an impressively learned academic.

Perdumes explained to them that when it came to making an impression, appearances were everything. Enveloping them in the gleam of his alabaster smile, he told the young man that he should change his old car and buy a new watch. Fine, but that was impossible, they could scarcely cover the mortgage…Eyes downcast, she confessed that her mother helped pay for her painting classes. Marvelous! Don’t worry, replied Perdumes’ smile. I’ll loan you as much as you need and you can pay me back in installments. He was a master of the art of silence. Without moving from his seat, his presence seemed to lose density while the couple made their decision. Of course, they would repay him as soon as possible. It’s just a springboard…Great! No problem. Would you like more coffee?

He also happened to know that some women in the building were interested in forming a reading group. Why didn’t she organize it? This time the silence was more ephemeral. The girl’s eyes lit up with an enthusiasm her husband hadn’t seen for a long time. Phenomenal! Don’t say another word. Would you excuse me a moment?

Within a few weeks everything was different. The young man was driving a modest new car; he checked the time regularly on his elegant casual watch. Every week, she listened to the heavily made-up ladies who spoke about anything but the books they had briefly skimmed through. His employers noted the change and began shake his hand when they met. They once asked him to join them for lunch in the small restaurant near the office. She was able to pay for her painting classes for as long as Perdumes’ clandestine subsidy to the ladies of the reading group lasted. Every weekend, the couple turned up with radiant smiles to present their repayments.

To explain his theory of secrets, Perdumes used the analogy of the reversible red velvet bags used by magicians. The first step is to show the audience that the bag is empty inside and out. Nothing hidden there. However, the trick consists in inserting a hand in the right place. The commonest secrets are as innocent as white rabbits. Then come the shameful secrets, greasy stains that can be removed with a little effort. As he honed his extraction technique, Perdumes became interested in the secrets that could only be invoked by a black magic ritual. They were barbs that gave pain by their mere existence: the smallest movement lacerated the soul in which they were embedded.

On one occasion, Perdumes noticed that the logo on a young neighbor’s sneakers had an A too many and was missing an E. When little Jorge felt the gleam of Perdumes’ smile scrutinizing his footwear, he knew the secret was out. He subjected his mother to a weeklong tantrum that only abated with the arrival of a box containing a pair of authentic sneakers. There was also the elderly lady in 4B who used to fill the bottles of holy water she sprinkled on her grandchildren on Sundays from the tap. Or the aged bureaucrat in 2C who boasted of his mistreatment of the Villa Miserias cleaning staff: “Better harness the donkey than carry the load yourself.”

Perdumes’ prying was sustained by an age-old activity: gossip. Having gained a little of a person’s confidence, he was able to access what they knew, suspected or had invented about others. It was an unashamed downward spiral: other people’s dirty laundry covered your own to the point where you created a hodgepodge of stinking gibberish, crying out in a muffled voice: “Deep down, we’re all disgusting, so there’s nothing to worry about.” It made no difference that the secret was an invention. What mattered was the perception of that dark thing and its tangled strata. Everyone had something to hide; other people found out about it. The gossip came alive, spreading like a virus that by nature mutated on infecting each new host. Attempts to deny the gossip gave rise to other, more poisonous rumors. Making use of the most innocent gestures, Perdumes would communicate that he knew the very thing no other person should know.

Very soon Perdumes had fabricated a network of correspondences woven from founded and unfounded rumors. Whether out of gratitude, respect or fear, the residents in his building adored him: all collective decisions passed through his hands. His indefatigable mind processed the situation until it hit on the two pillars of Quietism in Motion: the theories of the sword and the tea bag.

The former was based on the equilibrium of unequal things, the distinctive characteristic of a good sword. It may be the blade that cuts, but it’s the hilt that is in control. When wielding a samurai sword, in order to obtain horizontal equilibrium, the extended finger must be placed on the juncture of the hilt and the blade. If the finger bears down slightly harder toward the blade, the greater weight of the hilt is magnified and wins the day. And from this came the Perdumesian maxim: cannon fodder should respect the rank of the person who holds the weapon. Hence the Quietism.

The motion came from the tea bag. Perdumes would ceremoniously pour the hot water from his antique porcelain jug into a white cup and slowly remove the tea bag from its paper wrapping, allowing his audience to confirm the absolute transparency of the water. The tea bag was then gradually introduced into the cup at an angle of ninety degrees to the surface of the water. Initially, nothing happened. Then, when the tea could no longer bear the scalding water, it exuded a thin, blackish thread that diffused into the water. Perdumes would accentuate the effect by a series of upward jerks. The tea seeped out evenly in all directions until the correct hue was attained. But if one were to move the bag around without rhyme or reason, what would happen, he would ask rhetorically. You might say, exactly the same, he then quickly replied, yet turbid tea is acidic and doesn’t have the same flavor. The motion is necessary, in its proper time and place.

After his informal conquest of the building, Perdumes’ foot soldiers went out to spread the word. Secondhand samurai swords began to be found everywhere. Others made their own from what looked like sharpened clubs, thus producing an epidemic of three-legged chairs. At times, the tea was replaced by other herbs: toloache, or devil’s weed, diffused like a form of plasma, slowly encapsulating the boiling water. In the end, no one could ever give a precise explanation of what Perdumes was talking about; Quietism in Motion had been born. When a couple of disheveled university types knocked on his door to reprove him, Perdumes knew that his spiritual conquest was complete. It was time to move on to action.

2

Why the hell did I shave when she’s said she likes me better with a bit of a beard? Max Michels reproached himself without moving away from the mirror. Did she really say that? Shit, I guess so. It’s no big deal, it’ll grow back in a few days. A few days? As if you’ve got much time left, you moron. We’ll see how much time I’ve got. Things are going to be different now. Yeah? If you say so. Good luck with what’s left.

By this stage, he’d learnt that the best way to escape from the voices of the Many in his head was to seek a zone of consensus. But those barren wastelands offered only a bitter composure, so instead he dived down into a recapitulation of the events that explained his present dilemma.

He went back to the time when the presidency of Villa Miserias was passed on by means of a procedure that was as opaque as everything around it: the outgoing president consulted the most longstanding families. The succession was so automatic it was boring.

When Selon Perdumes became one of the notables with the right to express an opinion, he cooked up a simple strategy for producing a change of tack: first, he gave his blessing to the heir apparent. It was never certain if he was aided by luck or surgical calculation, but the candidate in question was Epifanio Buenaventura, who was due to inherit Buildings 17 and 19. According to protocol, the election could not take place before the stipulated lapse for registration. However, on the last day an extremely unlikely candidate put her name down: a woman in her early thirties named Orquídea López. After a brush with radical ideas on a steep downward path, the costs of everyday life had transformed her into a public sector employee. Orquídea was the nearest thing to dissidence Villa Miserias had ever seen: everyone assumed her to have been guilty of the wave of hood ornaments stolen from the most elegant cars on the estate. Her revolutionary fervor fizzled out as her comrades swapped the idea of guns for shoulder pads and Friday-night Cuba Libres. Orquídea lost her last illusions when the most extreme member of the clan registered for federal taxes: from that moment she changed into a receptacle in search of defining content. Quietism in Motion appealed to her disillusioned side: it seemed to atomize the weight of life in a social setting and deposit it on the individual. Orquídea was tired of moral vestments that didn’t match real human dimensions.

The paradox is that she didn’t come from that class of people who have a head start in life. And for this reason she tenaciously clung to each new rung of the ladder she managed to ascend to. She didn’t miss a single alteration in the world around her: changes of image, the arrival of new furniture, extravagance at quinceañeras, men going off with younger women. Even things that didn’t concern her seemed an affront. Why was everything so easy for some people when it had been so hard for her? Why did everyone pay the same maintenance costs when they didn’t get the same level of service? People who lived nearest the security lodge were better protected; in contrast, others suffered more from the stink of trash. Every month she would make variants of these complaints to the administration office.

When the outstanding interest of her downstairs neighbor’s debt was waived so he would pay off what he owed, Perdumes had to take her to his apartment and try to calm her. Of course she was right. The most frustrating thing was that everyone else was blinded by sentimental conformity. Had she noticed the gradual deterioration in Villa Miserias? Oh, yes, Don Selon, but that riffraff get what they deserve. Stupendous! Though it’s not really their fault, Orquídea. They’ve never had it any other way. Oh, I know, but what do I do? Sit here twiddling my thumbs? Of course not, Orquídea. But sudden upheavals are bad for everyone. Don’t forget that, bad for everyone. Would you excuse me a moment?

Perdumes returned with a sword and a porcelain jug to explain the details of Quietism in Motion. First, we have to accept things as they really are, not how we’d like them to be. If inequality is inevitable, why not accept that as a point of departure? Oh, I don’t know, Don Selon. Where does that leave those of us who started at the bottom? Splendid! That’s what I’m getting to. It’s the reason why I brought my jug. As you well know, those who make the effort get their reward. Unfortunately, they are always in the minority, and it’s not fair that the others should get the same, just because. Let’s see, I’m going to ask you a question. Don’t you find it beneficial to watch your show-off neighbors going on cruises? It’s well known that people better off than ourselves help us to try to improve. If the carrot is too close to the horse, the animal will stop walking. The problem is that some people think we’re all thoroughbreds by right.

The dialogue with Orquídea went on for weeks, moving slowly toward more specific issues. Then Perdumes suddenly, with an air of indifference, asked the question: Why don’t you put your name down for the election, Orquídea? Jeez, Don Selon! What election? We all know the same old people appoint the next president. Extraordinary! You’re right, but only because we’ve let them, Orquídea. Have you read the regulations of Villa Miserias? I have. If there’s more than one candidate, they organize elections. Hmm, so why has it never happened, Don Selon? Brilliant! For the same reasons we’ve talked about so often, Orquídea, but I believe an increasing number of residents are opening their eyes. Have you seen whose name they’ve put forward this time? Yes, that halfwit Epifanio Buenaventura, who can’t even talk properly. Incredible! Didn’t I tell you, Orquídea? You’re ready for action. If you don’t mind my saying so, more than a choice, I believe it’s a duty.

The young assistant in the administration office suspected something was wrong: Orquídea López didn’t fling open the glass door. This time she slipped quietly in and stood motionless in front of his desk, regulations in hand, savoring the moment before the assault. After pinning her victim in his seat with her stare, she announced her intention to register as a candidate. Taken unawares, he began to seek a response among the disorganized papers on the desk, but was unable to come up with anything better than noting her details on a blank sheet to gain time while he consulted his superior. Making an enormous effort to contain her laughter, Orquídea demanded the stamped acknowledgement of receipt she still has framed in the living room of her apartment.

Having closed the office early, the young man telephoned his superior to explain what had happened. An emergency meeting was called and Selon Perdumes was in attendance. So much excitement made Epifanio Buenaventura’s tongue even clumsier than usual; the scant hair combed across his crown was beaded with sweat. He gave his father a pleading look in the hope of being able to abandon the race. No one knew quite what to say. They racked their brains in search of a strategy to ensure the victory of Epifanio, that representative of the only way of life they knew, but every word he spoke only sunk them deeper into despondency.

“De thing is dat I don’t know de firsht thing about campaignsh.”

Defeat was a foregone conclusion. Even Perdumes felt sorry for Buenaventura, and attempted to alleviate his suffering. Thus the regulations that would, from then on, be enforced in political contests in Villa Miserias were created.

3

REGULATIONS FOR THE VILLA MISERIAS PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS

1. IN ORDER TO INTRUDE AS LITTLE AS POSSIBLE INTO THE LIVES OF THE RESIDENTS OF OUR COMMUNITY, ELECTORAL CAMPAIGNS WILL LAST A MAXIMUM OF ELEVEN DAYS.

2. TO GUARANTEE A MINIMUM OF FAIRNESS, ALL RESIDENTS WILL BE CHARGED AN EXTRAORDINARY SUM TO BE SHARED BETWEEN THE CANDIDATES.

3. PRIVATE DONATIONS WILL BE ALLOWED UNDER THE FOLLOWING CONDITIONS: THE AMOUNT AND NAME OF THE DONOR MUST BE DULY REGISTERED WITH THE ADMINISTRATION. THIS INFORMATION WILL THEN BE KEPT IN CONDITIONS OF STRICT PRIVACY SO THAT THE VARIOUS DONATIONS CANNOT INFLUENCE THE ELECTORATE’S DECISION.

4. EACH BUILDING WILL ORGANIZE ITS OWN MEETING TO CHOOSE THE CANDIDATE TO BE GIVEN ITS VOTE. TENANTS MAY ONLY ATTEND THIS MEETING BY PREVIOUS WRITTEN AUTHORIZATION OF THE OWNER OF THE APARTMENT.

5. ANY UNFORESEEN DIFFICULTIES AND THE DUE SANCTIONS FOR VIOLATION OF THE RULES STIPULATED IN THIS DOCUMENT WILL BE RESOLVED BY THE BOARD. THE ELECTORAL POWERS OF THIS BOARD WILL BE PUBLISHED AT THE APPROPRIATE MOMENT.

During the period when this document was being drawn up, several objections were raised and were immediately cut short by Selon Perdumes’ alabaster smile. Who’s going to want to fork out money for an irritating, shallow spectacle? No price can be put on the right to make decisions. Why are people who rent second-class residents? The vision of the owners is more likely to protect what in reality belongs to us all. What will candidates be able to buy with the private donations? The donations are simply to help the transmission of a message. The residents’ consciences aren’t for sale. When are we going to decide on the regulations for the intervention of the board? Would you excuse me a moment?

The public reading of the document sank all doubts as a stream of water sucks the spider into its eddy. The faces of all present displayed grave satisfaction; they suspected they had created something that was greater than the sum of its parts. No one in his right mind would dare to question it. Epifanio Buenaventura became unusually fearless:

“And we can convinshe dem dat I’m de besht candidate, can’t we?”

Selon Perdumes kept his alabaster smile in check. Quietism in Motion had just cut its first tooth.

4

After confirming yet again that there were no tea bags left in the packet, Max Michels wavered between tearing it to pieces for its insolence and ensuring that he was really alone in the apartment. You only got away with it because she was running late, you miserable sod. And what if she finds there’s no tea for her breakfast? Better buy another packet before going and committing the supreme idiocy of becoming a candidate. I’ve got better things to do, she can buy her own fucking tea if she likes it so much. Huh, you’re all balls when she’s not around. Let’s see if it’s the same tonight.

At the level temporarily reserved for what he understood as his Himself, Max wondered if he really was about to add his name to the list of previous Epifanio Buenaventuras. Thinking it over, registering for the election was an enormously arrogant act. What did he hope to gain by it? Before being obliged to conclude that what he was searching for was to be found somewhere else, he preferred to finish off his interior monologue. Better to stick with the dreaded Epifanio than see yourself turned into him.

The residents of Villa Miserias reacted to the news of the electoral reforms with indifference. Few of them showed much inclination to follow the spectacle closely, but it soon became apparent that this was an advantage for the candidates. Even Buenaventura and his team realized that hardly anyone had what it took to form a sound opinion: the challenge was to learn to speak the dialect of the guts.

Even though—for obvious reasons—there was no question about the result of the contest, Orquídea floored her opponent with a speech that, if more abstract, also managed to strike the simplest of chords. In contrast to Epifanio, who promised to sort out the plumbing and construct more play areas for the children, Orquídea sketched the porous outlines of a new life: the life they each deserved. She spent a whole night adapting one of her former mantras to fit the occasion. Using the same essential elements, she tweaked them to appeal to the dormant aspirations of her voters:

SINCE NEEDS ARE DICTATED BY ABILITIES, VOTE FOR ORQUÍDEA LÓPEZ

Every apartment in Villa Miserias received Orquídea López’s campaign leaflet, which basically asked the residents why their futures should be limited by other people’s aspirations. To illustrate her case, she used the example of Chona, the elderly lady in Building 23, whose putrid pension barely met the needs of herself and her beloved canaries. Orquídea’s leaflet demonstrated that if she didn’t have to to pay the communal water charge, Chona would be able paint the rusty cages in which her only companions lived, and buy special food to make their plumage glossier. And neither was there any reason why she should pay the same for the repairs to the front door of the building when she clearly used it less than the neighboring families.

As Selon Perdumes’ outstanding pupil, Orquídea made use of the storytelling tradition to reinforce her message: the reverse side of her leaflet recounted her personal version of a fable clearly demonstrating the benefits of the adage that the whole is never more than the sum of its separate parts. She explained to the residents that the writer of these words was one of the first people to become aware of the serious error of talking to humans about what they should be, instead of what they really are. However, the fable needed updating since hers was not an age in which innocent little bees fitted the bill. The new metaphor had to be omnivorous, must have to fight for its life before going out to face the world, and must even be the enemy of its own siblings. Orquídea was fascinated to learn of a creature that was in the habit of throwing itself to the ground, its tongue hanging out and its eyes turned upwards, so that when its adversary—taking the animal for dead—relaxed its guard, it was able to flee. Without such cunning, the young animal would not even reach maturity as the mother only fed and protected two thirds of each litter, so that the least able were even spared the suffering of going through life, dragging their shortfalls along behind them. Orquídea was overcome by an ecstasy of inspiration and put the finishing touches to her electoral leaflet with a speed that was surprising, even for her.

THE FABLE OF THE OPOSSUMS

IN A POSSUM’S NEST

THERE’S NO PLACE FOR FOWL

THOSE WHO CAN’T GAIN THE BREAST

HAVE TO THROW IN THE TOWEL

THE BEES THAT GIVE HONEY

HAVE GONE UNDERNEATH

STORIES THAT ARE SUNNY

ARE NO USE TO THE THIEF

ENOUGH OF FALSE SERMONS!

CAN’T YOU SEE THERE’S NO BALM?

WHY WISH FOR DELUSIONS?

THEY CAN ONLY DO HARM

WRONG MAKES FOR RIGHT

OH FABLES OF YOUTH!

WRONG BECOMES MIGHT

AND THAT IS THE TRUTH

THE INDIVIDUAL IS KING

THE GROUP IS PURE SCHLOCK

NO COMPETITION WITHOUT SWINDLING

WHY IS THAT A SHOCK?

LAWS PROTECT THE ELITE

IT’S TIME TO TURN ON THE LIGHT

WHY TAKE A BACK SEAT?

JUDGE THE POOR IN THEIR PLIGHT

EACH TO HIS SORORITY

ACCRUING HIS WEALTH

BLESSED BE POVERTY

LET’S DRINK TO ITS HEALTH

IF WE WANT TO KEEP OUR BIRTHRIGHT

LET’S FORGET SAYING THANKS

SQUARE UP FOR THE PRIZE FIGHT

WE’RE BREAKING THE RANKS

VOTE FOR ME: I AM YOU.

The residents agreed: the time had come to leave paternalism behind. Forty-four buildings decided to come of age. By a majority vote, Orquídea López became the first female president-elect.

The process gave rise to another local tradition: Juana Mecha had been head of the Villa Miserias cleaning staff for years. The sound of her broom was an unofficial signal for the start of each working day. She was so regular in her habits that mothers knew if they were late dropping the kids off at school by her location when they left the building. She was also given to expressing herself in enigmatic maxims, most of which were ignored by the people to whom they were addressed.

In order to avoid the rush hour on public transport, Orquídea would set out for the office early, so she was always the first to leave. Her automatic “Good morning, Señora Mecha” was returned each day by some snigger-inducing phrase. On one of the days when Orquídea was still hesitating over whether or not to sign up as a candidate, her greeting produced a cryptic barb: “If you put everything in the wash together, the clothes lose their color.” Orquídea had spent the whole morning trying to decipher her words. When she decided on an interpretation, she knew what to do next and hurried to inform Perdumes that she accepted his challenge. She was completely unaware she’d inaugurated the strict custom of consulting the beige-uniformed oracle.

5

Looking back on it, Max Michels realized that Orquídea López’s historical legacy had been, first, to act as a lever in the destruction of the existing structures, and then to be a slightly inefficient steamroller. She had smoothed the path for Villa Miserias to leave Villa Miserias behind and become Villa Miserias.

Her term in office inaugurated the reign of quantity: the will to count everything. She had promised a form of justice tailored to fit each individual’s specific dimensions. This required the residents to provide information that could be statistically represented: the hours of sunlight entering through each window; the number of minutes they spent sitting on the communal benches; their proximity to the green areas that purified the air. A coefficient was created to measure the benefit each individual obtained from the collective services, including such variables as the frequency with which the barrier was raised to let cars through, usage of the entry phone system and even the amount of time the lobby of each building remained dirty due to the order in which they were swept. The residents began to view one other in terms of their numerical values. The premise involved putting a value on the cost-benefit ratio of each and every soul living on the estate.

Orquídea’s other great legacy was the transformation of the security force. The guards were used to busting their breeches watching television in the security booth: they didn’t even have to shift from their chair to raise the barrier; the rounds they made of the estate were more a matter of stretching their legs. Orquídea started by putting them into uniform: the tight-fitting black suits and berets gave them an air more comical than threatening. There was an attempt to have them armed with pistols, but money was short and, in any case, they didn’t know how to use them. Pepper spray became the preferred option. The first week, two guards ended up in the sick bay with their faces burning from the effects of the new security device, one due to a practical joke played by a colleague, and the other from having pointed the can in the wrong direction while testing how far the spray reached.

They had soon caught two petty criminals trying to burgle an apartment in Building 24. The circumstances couldn’t have been more compromising: the petty thieves had broken in in broad daylight, armed with a screwdriver, stinking of Resistol glue, and had gotten stuck in the internal wiring duct while making their escape. It was more a rescue attempt than an arrest. They were left sitting for hours, in full view, surrounded by a patrol of the reinvigorated security squad. The verdict was almost unanimous: the residents felt safer after the professionalization of the forces of law and order.

To mark the end of Orquídea’s term in office, Perdumes organized a farewell dinner. He gave her a token of appreciation, specially commissioned for the occasion: a bronze sculpture on a marble base, with a gold plaque inscribed with Orquídea’s name and the dates. The statue was of an ambiguously sculpted man, leaning forwards, in a position of great strain. With both hands, he was pushing an enormous sphere. The man represented movement. The sphere, impassivity. The New was still far off but Orquídea López had been the piston chosen to set the ball rolling toward it.

6

During the following periods, the outline of Villa Miserias’ electoral ritual was more clearly defined. By means of signals and coded language, Perdumes encouraged or frustrated aspirations. He investigated the most intimate affairs of the candidates. It soon became obvious that the least fruitful way to participate was by demonstrating any intention to do so. Those who put themselves forward independently were subtly destroyed. Rumors would begin to circulate about their habits and proclivities: one left his dog’s urine lying on the living-room floor for days; another had borrowed money from his mother-in-law to get a hair transplant. The rumors were never completely destructive: they were warnings about what would happen if the person in question didn’t desist. He should go about his normal life and simply wait for the appropriate signal.

A dichotomous formula came to be the norm. Its plurality was based on a moving axis, situated more or less halfway between the two candidates. Generally, the contrasts were basic: man/woman, young/old, good-looking/plain. In this way, an impression of difference was transmitted. The reality was that the following two-year periods were almost interchangeable: the same person in a different format. The estate was on a steady course.

At the end of their term, they all received the same statue, with slight updates. The hill on which the figure stood went progressively upward and the sphere advanced a little farther. It was a matter of creating sufficient inertia for it to move unaided, flattening every obstacle that came in its path.

7

The day he decided to stand as a candidate, Max Michels dressed slowly and deliberately. While he was searching every corner of the apartment for his socks, he came across a thick, leather-bound volume on the study table. The night before, he’d been consulting it until the early hours, unable to focus. Irrespective of the content, the shadowy outline of a female figure would begin to form on the paper. Although Max had attempted to quash it by turning the page, each one seemed identical to the last, and the form had gathered new strength to return to torment him.

He aborted his exhaustive search for the socks when he noticed they were in his hand. While he was putting them on, he tried to return to the world of shadows, but a silent voice cut in: Shut up, you moron! Better get a move on before you change your mind. Or don’t you have the balls?

It was no moment for confronting the Many, so he opted for taking refuge in continuing his recollection of the situation he’d so often gone through in the past. He was well aware that the beginning of Villa Miserias’ contemporary history was marked by the sacrifice of Severo Candelario, the only previous person to register his candidacy without Selon Perdumes’ permission. It could even be said everything that had happened before consisted of the construction of a two-level altar. One cosmetic and visible; the other deep and intangible.

The former involved the introduction of the relevant modifications. The majority of buildings already had discussion groups on Quietism in Motion, but the most stalwart had taken things to levels never imagined by its creator, particularly in relation to the degree of scientific precision involved. To differentiate themselves from the many other failed ideologues, they clothed the theory in an almost irrefutable dogma: mathematics. They understood that if one starts from the appropriate assumptions, it is possible to come to the most implacable conclusions. Their minds were like scrap metal balers fed by a particular configuration of reality, and compressing it into a series of theorems that, in essence, proved the same thing: individual destiny can be based on nothing other than a person’s abilities. Hypnotized by the demonstrable, they didn’t realize that their path transformed the very conception of ability. They were like children who create imaginary friends only to then blindly follow their commands. By means of indecipherable algebraic progressions, they reified the virtue of a lack of scruples. From then onward, those who put their own interests first would be the ones to stand out from the crowd. Mathematics expunged any last vestige of guilt. In fact, they turned it on its head: the greater the determination to excel, the greater the benefit to those others. The new common goal was to ensure the cake continued to grow forever. Talking about sharing it out became a poor-taste anachronism.

The process started with the individualization of the service charges, calculated on the base of the coefficient. The apartments on upper floors paid a higher percentage as it required more energy to pump the water from the cistern up there, the gas had to run through more yards of piping, and they were less afflicted by the racket of the daily bustle down below. The coefficient also addressed the other factors mentioned above, thus condensing the defining characteristics of each person with respect to his peers. Rather than displeasing them, the level of the coefficient became a status symbol. It was not uncommon to see residents open their statements in front of others, arrogantly displaying feigned surprise at the exorbitant rate they were being charged.

The next step was to modify the weighting of each residential unit. If a building contained people of greater value, it was only appropriate that their vote should have more impact. A mathematical model demonstrated that this led to maximization of the well-being of the whole. Despite the fact that lip service was paid to the normal procedure, in reality a handful of buildings made the decisions.

The reforms to the regulations and perception of the estate were in the public domain. Anyone could find out about them. However, another, parallel movement also took place: underground and more expansive. Selon Perdumes called it “poetic mortgaging.” With his small initial capital, he was able to get his hands on several apartments, strategically placed throughout the estate. He negotiated directly with the owners. The tenants only discovered what was happening when they received a jubilant letter informing them of two things: first, Perdumes was the new owner of the apartment; second, their lives were about to change. For a modest deposit and absurdly low monthly repayments, they could buy the apartment and not have to go on throwing away money on rent. They didn’t have enough for the down payment? They could borrow that too. The letter was a textual version of Selon Perdumes’ alabaster smile.

There was a stampede of tenants wanting to take advantage of the opportunity. With the down payments, Perdumes bought more apartments, some of them also on credit. Given the number, he negotiated interest rates that were lower than he charged, and so he was able to pay off his loans with the radiant new owners’ monthly contributions. In time, a large portion of Villa Miserias was involved in the scheme. Selon Perdumes gloated. His role as an intermediary multiplied his fortune and, despite not being the outright owner of the apartments, he did possess something more valuable: the dreams of the residents of Villa Miserias.

8

There were two buildings that, for very different reasons, clearly stood out from the others. The reason for the conspicuousness of the first was grounded in the yearning for prosperity, which was producing increasing amounts of garbage. The truck picked it up every morning but, even so, a new accumulation was continuously piling up in the rusty containers. The residents of the building adjoining these containers were convinced they were unsanitary: the smell permeated everywhere, throughout the whole day. Not even the lowest interest rates could persuade anyone to buy those apartments. People considered it beneath their dignity to own something in what became known as Building B, and moved out at the first opportunity. Selon Perdumes decided to change his strategy.

At that time, Villa Miserias’ employees tended to live in distant, cheerless communities. They left their houses before the sun had risen and returned under the shelter of the clouded night skies. In addition, the employees often had to work overtime, to the extent that, on occasions, they would get home in time to have dinner, take a nap, and shower before setting out again. This situation was a headache for the administrative department of the estate. The lightest traffic jams caused the employees to arrive late; they were reluctant to work beyond their shift; they were constantly suffering nervous illnesses and their uniforms were always sweaty from being canned up in the public transportation. Selon Perdumes burst into a board meeting with a solution.

Building B was by then almost empty. Perdumes had been gradually rehousing the residents; a few others had moved out of the estate. With the appropriate redesign, he suggested, Villa Miserias’ workers could live there. It was a delicate situation; they needed to tread carefully. But also be firm. In order to clearly differentiate Building B, it would be painted light ochre. The fittings would be replaced by ones of poorer quality and taste.

The trickiest problem was yet to be resolved: how would the workers pay to live there? He wasn’t thinking of offering his mortgage scheme to more than two of them: Juana Mecha and Joel Taimado, the boss of the Black Paunches, as everyone now called the security squad. Perdumes handed a copy of his proposal to the board, as a mere formality before it was announced.

9

PROPOSAL FOR ACCOMMODATING WORKERS IN BUILDING B

1. OUR ESTATE SUFFERS THE UNDESIRABLE CONSEQUENCES OF THE DISTANT HOUSING OF OUR WORKERS. FOR THIS REASON, WE ARE OFFERING THEM THE CHANCE TO RENT IN THE SO-CALLED BUILDING B, AS SOON AS THE APPROPRIATE ADAPTATIONS HAVE BEEN MADE, THE COST OF WHICH WILL BE BORNE BY THE ADMINISTRATION.

2. OUR COMMUNITY HAS MADE A GREAT EFFORT TO BREAK WITH IDEAS THAT HINDER ITS MOVEMENT TOWARD THE FUTURE. WE CANNOT EXEMPT THE WORKERS FROM THE PRINCIPLES BY WHICH WE NOW LIVE, NEITHER FOR THEIR OWN BENEFIT NOR OURS: FOR FINANCIAL, ETHICAL, AND MORAL REASONS, IT IS IMPERATIVE THAT THEY FULLY COVER THE CORRESPONDING COSTS OF THEIR NEW HOUSING.

3. IN RECOGNITION OF THEIR FINANCIAL MEANS, THEY WILL BE OFFERED A MIXED SCHEME THAT WILL MEET THE NEEDS OF BOTH PARTIES, AND COVER THE MONTHLY MORTGAGE PAYMENTS OF THE APARTMENTS.

3.1. THE ADMINISTRATION WILL DIRECTLY RETAIN A THIRD OF EACH WAGE. THIS SUM WILL BE PUT TOWARD THE MONTHLY PAYMENTS.

3.2. THE WORKING DAY WILL BE EXTENDED BY TWO HOURS. THE ENSUING INCREASE IN PRODUCTIVITY WILL ALLOW A NUMBER OF WORKERS TO BE LAID OFF. THE SAVINGS OCCASIONED WILL BE PUT TOWARD THE MONTHLY PAYMENTS.

3.3. IN ORDER TO MAKE SAVINGS IN THE COST OF FOOD, FROM NOW ON RESIDENTS WILL BE ASKED TO TAKE THEIR LEFTOVERS TO THE CANTEEN, TO BE EATEN BY THE EMPLOYEES. THE SAVINGS OCCASIONED WILL BE PUT TOWARD THE MONTHLY PAYMENTS.

3.4. ADDITIONAL ECONOMIES WILL OCCUR IN RELATION TO MEDICAL COSTS AND SICK, LEAVE SINCE LENGTHY TRAVEL TIMES CAUSE A VARIETY OF AILMENTS AMONG OUR EMPLOYEES. THE SAVINGS OCCASIONED WILL BE PUT TOWARD THE MONTHLY PAYMENTS.

4. IN ORDER TO ASSIST THE DOMESTIC ECONOMIES OF OUR WORKERS, IN ANTICIPATION OF POSSIBLE POOR BUDGETING, MECHANISMS FOR REGULATING BASIC SERVICES WILL BE SET UP. IN THIS WAY, THEIR COEFFICIENTS WILL NOT EXCEED A QUARTER OF THEIR INCOME.

5. WHEN THE MORTGAGES HAVE BEEN PAID OFF, THE BOARD WILL DECIDE ON THE RELEVANT PROCEDURE. UNTIL SUCH TIME EACH APARTMENT WILL REMAIN IN THE NAME OF THE ORIGINAL OWNER.

The first person to receive the proposal was Juana Mecha. Broom in hand, she enthusiastically exclaimed, “The mules will get fewer beatings,” which escalated to a euphoric “Property will make us free” when Perdumes notified her she was to become a homeowner. In contrast, Joel Taimado’s response was the characteristic “Uh-huh” with which he impassively assented to everything from behind the dark glasses covering his face down to his three-whisker mustache.

The workers very soon began to move in. Overflowing boxes wound around with tightly knotted rope, tables with legs that didn’t match, and grannies in wheelchairs colonized the ochre building. No one had foreseen the size of the families. In some cases, an apartment was divided between two employees, in a temporary decree that became permanent. The regulated lighting coated every corner with its subdued yellow; the cap on the use of water left more than one person covered in soap mid-shower. In the staff canteen, a certain amount of initial disgust had to be overcome when it came to the banquet of leftovers, which sometimes included half-eaten chicken legs, soup ready-seasoned with lemon and hot sauce, rock-hard beans mixed with rice, and cheese. Some preferred to accustom themselves to cold food as a means of neutralizing the envious glances directed at those who managed to receive protein. To compensate for the drop in wages, several employees moonlighted, doing the odd jobs the owners of the apartments preferred to avoid. The project was pronounced a success. The workers had decent housing and labor relations improved notably. The members of the residential colony got much more for the same money. It was a fine adjustment of the gears that drove Villa Miserias.

10

The other building to escape the omnipresent gray was farthest from Plaza del Orden, the social and geographical center of Villa Miserias. Despite being on the margins, it immediately caught the eye. The two façades visible from within the estate displayed an intervention by a young artist, Pascual Bramsos: a paint-rollered giant composed of hundreds of silhouettes of miniscule men. The figure was in free fall, having received a blow from an abacus thrown by a chameleon brandishing a catapult above its head. Bramsos was intelligent enough to start with the colossus, so the board members thought the allegory of union it transmitted funny. Then, working the whole night, he created the homicidal chameleon. It was well before noon when the order to return the building to its gray normality was issued. Bramsos armed the neighbors, and a hail of eggs rained down on the man charged with the eradication of the work. He only got as far as castrating the giant with a brushstroke to the groin. The author of the work decided to leave it that way as a finishing touch. Perdumes used to amuse himself looking out on it each morning when he got out of bed.

The most eloquent thing that could be said about the estate’s residents was that the sum of their parts exceeded, in every sense, their whole. Having pursued imperfect Utopias for some years, they tended to air their bureaucratic frustrations by giving their opinion on anything and everything, just to have something new to spout off about. After Building B, they started on the one with lowest overall coefficient: its influence was close almost non-existent. It was also the only one to have three separate residents’ groups with pretensions to legitimacy, but which never sent delegates to the general assembly.

11

Such was, in broad outline, the general panorama of Villa Miserias when the schoolmaster Severo Candelario became the hinge that would close the door to the past and allow in the whirlwind of dust still blowing at the time of Max Michels’ decision. Before leaving his apartment, he looked contemptuously at his friend Pascual Bramsos’ painting hanging on the wall. For a moment he believed the frame was shaking, that it was trying to detach itself, as if catapulted by some irresistible force. Before this could happen, he took hold of it with both hands and carefully placed it on the floor. For the last time, he stood directly in front of the phrase written on the wall, hidden by the work. The fact was, Max was about to take a quantum leap toward discovering just how big he was.

As he set out, Max weighed up the situation, taking into consideration the reasons that, in their moment, had been behind Severo Candelario’s actions. In comparison to Max, who was aware—precisely thanks to Candelario's misfortune—of the insurrection involved in his decision, the teacher had lacked the necessary guile to understand the magnitude of his actions. Candelario had been able to appreciate the texture of the details but not the whole picture. He’d seen the chance to add his voice to something that worked, and so had decided to take an active part in it. His enthusiasm had prevented him from correctly interpreting the obstacles put in his way when he asked for the registration form, or the fact that he was the only male candidate without a mustache in living memory. His campaign had been anything but radical; he helped carry the old ladies’ shopping bags, asked the children about their favorite superheroes. At several years’ distance, the outcome of the story rested on a single detail, his electoral slogan: “With your constant help we’ll get better and better.” It was based on pedagogic principles such as the importance of each cell playing its part for the good of the whole and the notion that untiring repetition leads to perfection. Without realizing, he was attacking the very foundations of Quietism in Motion.

Candelario was in the habit of taking things calmly. Years of teaching had taught him that the task of molding souls required perseverance, a quality clearly expressed by his most treasured possession: a growing collection of yearly albums of black and white photos. On each odd-numbered page, a photograph was pasted in exactly the same place. Always the same image, taken every day at 7:19 in the morning, from the same angle. Even when he caught pneumonia, he managed to persuade the doctor to allow him his daily expedition to photograph the tree growing in the green area behind his building.

He had begun to portray the tree when it was still a timid shoot. With the passage of time, it became a proud willow, weeping majestically in all directions. If adjacent photos were compared, it was impossible to see any differences. But then, with an expression of childish glee, Candelario would take the album in his hands and rapidly flick through the pages. The metamorphosis of the willow caused him a spasm of tenderness. With ant-like diligence, Candelario used to say, his camera had captured the unfolding of the tree’s soul. After taking his photograph, he would stand, rapturously contemplating the willow, hunting for a tangible difference from that other tree, portrayed the day before. His perpetual failure to find one left him in ecstasy. Then he would set off for school, ready to add a pinch of education to the young minds in his charge.

He was a man of singular ideas. After the years spent studying the great masters, what could he say that was new? It seemed to him blasphemy even to attempt it; the future was set in stone. This was the basis of his decision to join the march of Villa Miserias’ progress. It wasn’t that he considered that progress to be either appropriate or desirable, but rather it was as definitive as the development of the willow he venerated and he thought it a duty to add his modest abilities to the project. Without any greater pretensions than being a single heartbeat more in the pacemaker determining the pulse of his community, Candelario put down his name for the Villa Miserias presidential election. When he was leaving the administrative office, his candidacy duly registered, Juana Mecha welcomed him to the contest with, “Skinned chickens had feathers once.” Candelario took this as an unmistakably good omen.

Neither Perdumes nor the members of the board feared for a moment that Severo Candelario would be able to beat the usual pair of throwaway candidates. They initially took his registration as an act of insolence. However, when they heard his slogan and gauged his potential for causing a breach, they resolved to destroy him without mercy.

“With your constant help, we’ll get better and better” constituted a threat on a number of fronts. The word “help” had been exiled from the collective lexicon. It was an anachronism. Time and again, it had been proven how useless it was to pull someone out of the swamp when he was determined to be there. The slime ended by soiling even the rescuer. This couldn’t be allowed in a community of high-flying individuals. Moreover, “we’ll get better and better” suggested a collective enterprise. The effort needed to get across the message of the individual’s responsibility in his destiny had been enormous…It was heresy to allude to their general impact. Candelario was a puppet of himself who could be ignored. But not his slogan. That same night, they asked Joel Taimado to start proceedings in the process of destroying the schoolmaster.

Candelario was so absorbed in his new mission that he didn’t notice his neighbors’ strange glances or the almost undetectable pauses before they returned his greetings. It was his wife who first made him understand something was wrong. On the second floor of their building, a young insurance salesman shared an apartment with a colleague. Almost every morning, he would take the same minibus as Señora Candelario to the metro station on their way to work. He began to leave a few minutes later, just in time for Clara Candelario to see him get to the main road as she set out through the asphyxiating exhaust fumes of the pedestrian walkway. One day, to clear up her concerns, she decided to wait for him. During their entire walk, the young man spoke on his phone to a client he’d woken up to remind that the policy on his old scooter was due to run out in four months. Once aboard the minibus, he refused to let Señora Candelario pay for them both—something they normally took turns in doing—despite the fact that he was clinging onto an external grab rail with just one foot on the first step. With his free hand, he managed to pass his crumpled bill to the driver, who was annoyed at having to give him change. Each time the bus stopped, he would get off to let new passengers on, without losing his place. When they arrived at the metro, he was the first to disembark and immediately disappeared into the station entrance. His neighbor saw no more of him.

Señora Candelario lost no time in discovering what was going on. The following morning, she planted herself in front of Juana Mecha and asked if she’d heard anything. Without in the least diminishing the trsssh trsssh of her broom, the latter simply responded: “People don’t like being reminded they’re people.” She pointed the handle of her boom to the façade of the building where someone had written the piece of graffiti Candelario would see repeated ad nauseum during the following days: “Candelario, you cunt, who are you going to humiliate next?” Taimado’s squad had done its job. The handwritten report detailed an incident the teacher thought had been long forgotten.

The official letter informing him he was to be relocated to a different school had stated that his only sin was naiveté. And possibly overzealousness. Each year a call went out for the Children’s Science Olympics, an event the authorities of the state primary school where Candelario worked as a fifth-grade teacher mostly ignored. In the year of the scandal, Candelario had among his students a very bright girl with a great talent for abstract thought. It was she who had brought the competition to Candelario’s attention. He began to pay her more attention in class, working with her on specifically designed tasks. As the difficulty of these tasks increased, the girl always rose to the challenge. Candelario put the case before the headmaster, who—after having made sure it wouldn’t involve any additional effort on his part—agreed to the teacher’s proposal: during the remaining month, the girl could stay behind for a couple of hours each day to prepare for the competition. The next step was to obtain the family’s permission.

The best procedure would have been to get this from the mother. The problem was that her job as a secretary prevented her accompanying her two children, so that it was their grandmother who took them to school each morning and collected them afterward. Even though Candelario’s proposal would mean taking the boy home and then returning for his elder sister, the grandmother signed the authorization without hesitation. Candelario promised to bring an extra sandwich each day so the child would not go hungry.

The children’s father had given up work at a very young age due to an accident in the laundry where he was working: he’d lost an arm in a supersonic rotary dryer while trying to demonstrate to a workmate there was no great risk involved in placing it there. The proprietors of the business had given him a modest payoff in order to avoid a lawsuit that was, in the end, completely groundless. From that time on, he’d spent his days at home, drinking in front of the television. His evenings alternated between episodes of violent behavior and yearning monologues related to the days when he’d been a whole man.

His children did their best to avoid him. Happily, he didn’t even notice the eldest wasn’t getting home from school until late afternoon. The dispute began during the week before the completion, while she was going over her exercises one night. The father staggered into her room to ask what the hell she was doing at that hour. No point in working hard just to get screwed like him. The child kept her eyes down. She attempted to defend herself from his invective by solving the problem with a trembling hand. The father tore the page from her notebook and left the room muttering incoherent insults. The child’s grandmother came out and he pushed her against the wall with his remaining arm. He then sat in the kitchen to finish off his plastic bag of pulque in giant gulps. Later, when the children and the old lady were deep asleep, it was his wife’s turn. She tried to control the explosion by explaining that the girl was preparing for a competition. Her teacher had chosen her and no one else. He couldn’t give a fuck. What did those frigging old ladies think? That they were better than him because they could ride a bicycle through the park? They were only good for one thing. His daughter wasn’t taking part in any competition.

His ban had little weight. First, because, by then, he had no practical authority. For his wife, he was like one of those intoxicated prophets of doom who shout in the streets, under the effects of a solvent-soaked rag. What’s more, he wouldn’t remember the episode the following day. His mornings were hostage to the hangovers that awaited the eggs his mother-in-law prepared for breakfast.

The tragedy was that the child had heard it all. Her mind paid no attention to the actual words and only processed what was not said: her dad had lost an arm and it was her fault. She stealthily hurried to her closet, being careful not to wake her grandmother or brother—with whom she’d shared a bed her whole life—took a plush turtle out of the plastic bag where it lived, and went back to bed, lying as near the edge as she could. She spent the rest of the night retching up acidic spume into the bag. In the morning, she got up early to rinse the bag out, but no longer had the strength to hide her trembling, the cold sweats and fever. Her grandmother put a damp towel on her head before taking her brother to school. The girl closed her eyes when she heard her father’s unsteady steps in the passage. She might as well not have bothered. He did nothing more than grab hold of the doorframe and then continue to the kitchen to sprawl in a chair and await his food.

On the third day of his pupil’s absence, Candelario begun to worry. At the close of classes, he asked the grandmother if he could accompany her home to see how the girl was doing. The elderly lady thought that was fine: she was delighted to be able to talk nonstop the whole way and slightly exaggerated her arthritic gait so the teacher would take her arm when they crossed road junctions. As they were nearing the dirt track where the family lived, they saw the girl playing with her dolls outside the house. Her grandmother’s shout brought her back to reality. When she realized who was walking beside her, she ran back inside. The schoolmaster picked up her two rag dolls before going into the kitchen.

“Who the hell’s this jerk and what’s he doing here?” was the father’s greeting to his mother-in-law.

“A very good afternoon to you, sir. I’m Severo Candelario, your daughter’s teacher. Delighted to meet you. It’s just a few days to the Science Olympiad and I wanted to see how…”

“My daughter’s not taking part in any competition. Get the fuck out and leave us in peace.”

“Sir, forgive the impertinence, but please allow me to tell you your daughter has studied hard and is very excited about the Olympiad.”

“Listen, you bastard, no one makes me look small in my own house.”

“Would it be asking too much for me to at least say hello to her?”

“Why the hell should you worry about us?”

“Sir, with all respect, it’s a good opportunity for your daughter. If she wins the Olympiad she can travel and get a scholarship.”

On hearing this last remark, the father lunged at Candelario. The teacher and the dolls leapt to one side and their aggressor tripped on a chair leg. He was unable to put his single arm out in time to save himself and his face smashed into the edge of the kitchen sink. The girl heard the noise and came in to find her teacher attempting to help her father to stand up. Seeing him there, his left eye closed and bloody, she gave such a shriek that the teacher’s reflex action was to let the victim fall again to attend to the child, who only stopped screaming long enough to take a breath and start again. The grandmother took her to her bedroom. Candelario attempted again to assist the father, who, in an effort to clean himself, had gotten blood all over his face. He lashed out one last time, with an accompanying stream of insults. The schoolmaster understood that it was time to throw in the towel. He managed to mumble, “I’m extremely sorry,” before hurrying out of the family home, consoled by the two sad rag dolls he still keeps as a souvenir of the only stain on his record.

Perdumes planted the story on a few fertile tongues. It immediately put out roots in multiple directions. In one version, Candelario had forced the girl to bring him a steak and cheese sandwich every day. In another, he’d tied the invalid father’s remaining arm and one of his legs behind his back. It was the most widely broadcast version that broke Candelario: he’d touched the grandmother and the girl in inappropriate ways, obliging them to carry out the fantasies he mimed with the rag dolls.

The haggard teacher abandoned the campaign without giving formal notification. He was so depressed by the silent disdain of his neighbors that he practically never left his refuge, except to take his daily photo of the tree. And then came the final insult. On the same day as it was announced that the winner of the election was one of the two usual faces—Candelario would go down in history as the only candidate not even to win in his own building—a handwritten circular, without any official signature, was slipped under his front door. It stated that the tree in the green area behind Building 23 was a threat to the safety of the residents and so would be immediately felled. One member of the condominium was required to supervise the team of technicians who would carry out the task. The board was notifying Severo Candelario that he had been assigned this responsibility. He was to present himself in the green area at 7:19 the following morning to undertake this task.

Candelario turned up a few of minutes early to take his farewell photo. Taimado’s Black Paunches, dressed up as tree surgeons for the occasion, were ruthlessly punctual. Their electric saws were indistinguishable from their twisted grins. The schoolmaster signed the order unleashing the carnage and they inexpertly began lop the defenseless tree, brutally attacking even the fallen branches, brandishing their saws like obese ninjas finishing off the enemy. The trunk was attacked from several angles. It was hours before they managed to penetrate it, but when the tree was unable to hold out any longer, irregularly shaped chunks began to tumble down. As darkness fell—Candelario had not even moved when the Black Paunches had interrupted their work to eat their usual leftovers—they called it a day, leaving just a few inches of the base, scarred by the teeth of the saws. Candelario didn’t notice when the last of the saws was switched off; he could still hear the roar in his head when Clara finally came to take his hand and lead him back to their apartment.

The schoolmaster continued his usual routine. Every morning at 7:19, he would go out to take a photo of the mutilated trunk that would never again grow. He continued to fill albums, continued to flick the pages for visitors. It was now an ode to the decomposition of matter. After his retirement, he would spend hours sitting on his bench, mentally visualizing every detail of his tree. He was never alone; the two tattered rag dolls, by this time without eyes or hair, accompanied him. Severo Candelario became a melancholy statue symbolizing a remote era, almost totally erased from Villa Miserias’ collective memory.

12

And what if they heap shit on me too?

Yeah, you bastard. But would it be any worse than this?

Stop talking, you jerk. Just go put your name down. Get it over and fucking done with.

Shit! There she is talking to Perdumes. That great asshole’s dazzling her with his smile.

Sure it was really them?

Positive. I’d better get a move on and stop imagining all this trash.

Imagining trash? If you say so. We’re always here, ready for any eventuality.

13

It was also a breach for Perdumes, a signal that the time had come to close the polygon, so that all its points led to the same place. The bulldozers arrived and with them the dust. The dust that, from then onward, would so thickly coat the existence of Villa Miserias that the inhabitants only noticed it when it wasn’t there. Outside the estate, they found breathing a strange experience, as if something were missing, until they returned to the customary dose of irritation the air administered to their lungs.

His plan to limit the horizon began with territorial expansion: Perdumes acquired an enormous vacant lot adjoining the estate. The founders of Villa Miserias had, in their day, met with a complex ownership regime that had made any form of financial transaction impossible. But Perdumes knew who to talk to and how much to offer. A solemn ceremony was organized to inaugurate the works, during which Perdumes’ alabaster smile hit the intervening wall without shaking it, signifying the beginning of the future. After the demolition of the wall, the present-day limits of Villa Miserias were traced out. With the machinery came the hands needed for the construction of the future. The plot was to be fitted out as a commercial zone with office space. The Villa Miserians would soon be able to realize their most hidden fantasies. Up to that moment, the reach of Quietism in Motion had been limited by the rigidity of its structure, which made it hard to separate the residents by value. From that moment a reverse order process began: Perdumes had traced out the course on which the tide of those with the possibility of grasping a lifejacket would travel.

The already successful financial engineering scheme was set in motion again. In theory, every inhabitant of Villa Miserias had the chance to own his own business: in reality only a few would. The bottleneck was formed by the residents themselves, draped in the material of their specific capabilities and ambitions. Those interested had to put an ear to the chest of the community to learn to hear the pulse of its desires. However, it was good news for everyone: those of limited vision could be employed as assistants, checkout operators, waiters, guards, janitors, and so on. The outside world was no longer beyond the confines of Villa Miserias.

The outer shell was quickly constructed. A concrete monstrosity, hygienic and functional. The interior spaces were also soon occupied by a range of outlets catering for everything from the most essential needs to those no one had ever suspected to exist.

One of the more successful cases catered to the youngest residents. It offered items for the amusement of children, including rattles, soft toys, and construction kits, but also strollers. Each of its articles was adorned with a glowing screen; interspersed between the cartoons and children’s movies shown there were commercials made by the store itself. This promoted family harmony since the children could spend hours sitting in front of the screen, their parents frequently watching with them. The children demanded the movie of their favorite bear, which they watched on the belly of a toy bear, along with the commercials in which the bear expressed itself happy to be their friend. Villa Miserias’ children would grow up in the shelter of the magical worlds contained in their toys. Their parents gladly forked out the cash in exchange for the free time it bought them.

In addition to the stores, not-for-profit organizations also sprung up. A group of refined ladies launched a cultural center called Leonardo RU, inspired by a new vision: they were tired of the arts being monopolized by a pedantic elite. Their project offered the ordinary person the possibility of buzzing with artistic creativity. A band of experts gave courses in literature, painting, music, and much more, in which they imparted the general principles of a work without the need to read it, see it or listen to it: there was absolutely no reason to expose the members of the center to complex issues. They even offered an express telephone service, something of first importance for social events. With just a single phone call, an overview of the book, movie, or exhibition of the moment could be obtained, including a critique of the weak points of the plot, plus arguments for supporting the notion that it was, in fact, a metaphor for the feeble human condition. There were members who complained because some other dinner guest had come out with the same idea before they could express it, so the experts began to prepare a variety of opinions, in the interests of fomenting plurality and debate.

In relation to creativity, they transferred to the field of the arts the age-old maxim that learning is, in fact, a process of remembering what you already know: the ladies believed that artistic talent was present in everyone, but the snobbism of the elites meant only very few had the right to enjoy it. Numerous artists in the making, assisted by the facilitators, created works of great technical skill.

In painting, the student would give a rough outline of the work. So as not to interfere in the creative process, the facilitator didn’t even listen to this. The student would then stand confidently before the canvas, the tutor took his arm and together they would begin to paint. Students were instructed to allow themselves to be carried away by creative ecstasy and to close their eyes during the process. The final product left them feeling so proud that it didn’t matter if it was somewhat different to what they had originally conceived. In musical composition, the facilitator would ask the student to say the third note in the scale and then write this down; then the fifth, the first and so on. In the end, without the facilitator having written a single note, a melody existed, written by the student. When it came to instruments, they were taught to play the separate notes or chords and these were recorded. A team of technicians then united them to form a complete song, played by the neophyte. At the end of each course there were exhibitions, dramatized readings, and prerecorded concerts where a new generation of artists were welcomed into the world.

A group of lawyers who believed in the importance of civic unity for eradicating injustice created an organization to help the stray dogs that plagued the streets of Villa Miserias. For a monthly fee, people could adopt a stray from their catalog. The sickly-sweet names beneath the photos would soften even the most hesitant heart. Once the canine had been adopted, the organization took responsibility for bathing and delousing it, administering its vaccinations, and feeding it. As the period of domestication was traumatic for the dog, the adoptive family was not allowed to see it until this had been completed, but they could send it letters and gifts. However, the organization was unwilling to be responsible for outbreaks of violence among the dogs, nor did the owners have time to oversee them. The solution was for the dogs to go on living in the street, receiving food and periodic attention from the association. Once a month, there was a supervised visit in their premises, where the family could meet its new member. The dogs tended to keep their distance; the owners were moved to see the results of the new lease of life they had offered the canines. They would tell it all the family news. Some smuggled in food, in violation of the rules of the organization, which didn’t want to have the dogs sniffing around the premises the whole day. Word got around in the doggy underworld, so that the number of strays went on increasing. They were divided between the fortunate that enjoyed the good life, and those left abandoned to their fate. The organization couldn’t do everything.

A bar called Alison’s also opened and became very popular among the male population of Villa Miserias. They gathered there to yell along with every variety of sporting event, transmitted nonstop, at full volume, on the giant screens covering the walls of the bar. Betting money was prohibited, but clients could make wagers using the trays on which the food and drink were served. The main attraction of Alison’s lay in a squadron of good-looking cheerleaders in civilian clothing who chatted with the clients every night. They were perfectly capable of dealing with unsolicited attentions, but the bald gorillas who acted as bouncers still prowled around them just in case. In addition to good looks, another factor was necessary to be employed there: an exceptional head of alcohol. The auditions were brutal. The girls were required to imbibe a succession of different drinks in a limited time, with television screens on and music blaring, to test their resistance in real life conditions. Every time something occurred worthy of an adrenaline rush—a goal, a hole in one, a spectacular crash, or savage knockout—they had to high-five, bonk heads or chests, and scream euphorically. Very few passed the test. The ones left at the end were invincible.

The procedure was for them to go up to tables for a casual chat; soon afterwards, they ordered a drink for which they immediately paid with money from the bar. They would down this in one, amid laughter and sporting banter. The men, however, couldn’t allow themselves to be left lagging; a new round quickly appeared with drinks for everyone. It was not infrequent for a visit to Alison’s to end in the involuntary use of the bald gorillas’ home-delivery service, even if it meant carrying the client. The only memory he would have of the evening was a photo of his group of friends hugging the good-looking girls. He would count the days until he could go back.

Each year, on the evening of the anniversary of the opening of the bar, only the most assiduous clients were allowed in. The festivities included a long-standing tradition: the table that chucked up most didn’t pay its check. As the clients sometimes missed the bucket provided for the occasion, by the end of the night the floor would be awash with a slippery, pinkish, lumpy slush. The record—three bucketfuls—was held by a group of middle-aged financial executives, who proudly held up their trophies in the photos displayed on the walls of the most paradisiacal bar ever imagined.

14

The reforms signified the commencement of perpetual change. From then onward, there would always be work in progress. Hence the dust. And also the noise. The transformations were like a loose hosepipe spraying water in all directions. To give them some coherence, Selon Perdumes brought in a man capable of measuring everything. G.B.W. Ponce had acquired great renown in the socio-scientific community for a statistical discovery known as the Ponce Scheme. After years of battling with his algorithms—his beaky condor face lost its glow and his hair started to gray—he’d managed to compress thousands of variables into a method he retained for his personal use, in spite of stratospheric offers to share his secret. Inspired by the philosophical notion that history is just an untiring repetition of itself, he proposed to condense the millions of correlations studied into an accurate predictive method: his aim was to quantify the eternal return. If all thought, every impulse or action is contained in the characteristics that define each individual, he could explain real events without having to wait for them to occur.

He investigated innumerable causal relationships, looking for recurring patterns. Beginning with the most obvious categories—social class, nationality, skin color, religion—he managed to corroborate common suppositions. In general terms, people’s thoughts and actions could be blocked out, according to the specific group they belonged to. Ponce concentrated his attention on the remainder, the minuscule deviations within a single group. Why did some millionaires wear denim jeans and jackets? What was the difference between adulterous believers and their chaste counterparts? What did women who lied about their age have in common? Why did hoods indicate a tendency to mindless acts of violence?

He tried out his theory on hundreds of the most elusive variables: the type of music listened to, favorite sexual fetish, being an early morning or night person. Almost all these variables fitted within more general categories, but some stood out for their predictive power. Among people with an average income, those who had had wooden toys were, as a rule, less given to accumulation; those who couldn’t dance salsa had a greater tendency for masochistic relationships. He refined and purified until he arrived at the famous Ponce Questionnaire. Seventy-one questions that summarized the narrative of human behavior. With a margin of error of ±3.14%, it could predict political opinions, consumption patterns, movie preferences, the cost of an engagement ring. Armed with his database, Ponce would consult his cyber-seer and note down the answers. It never failed on the outcome of an election, the sales volume of a new model of car, the numbers of demonstrators at a protest march, or the average abortion figures in a particular stratum of women.