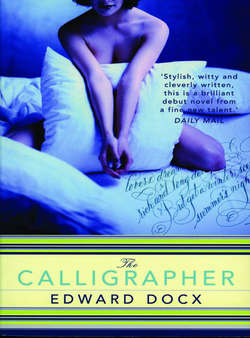

Читать книгу The Calligrapher - Edward Docx - Страница 8

1. Confined Love

ОглавлениеSome man unworthy to be possessor

Of old or new love, himself being false or weak,

Thought his pain and shame would be lesser,

If on womankind he might his anger wreak,

And thence a law did grow,

One should but one man know;

But are other creatures so?

Are sun, moon, or stars by law forbidden,

To smile where they list, or lend away their light?

Are birds divorced, or are they chidden

If they leave their mate, or lie abroad a-night?

Beasts do no jointures lose

Though they new lovers choose,

But we are made worse than those.

Who e’er rigged fair ship to lie in harbours,

And not to seek new lands, or not to deal withal?

Or built fair houses, set trees, and arbours,

Only to lock up, or else let them fall?

Good is not good, unless

A thousand it possess,

But doth waste with greediness.

Like so many people living through this great time in human history, I am not at all sure what is right and what is wrong. So if I appear a little slow to grasp the moral dimensions of what follows, I’m afraid I will have to ask you to bear with me. Apologies. It’s a difficult age.

Actually, I do not believe I was behaving all that badly when these withering atrocities first began. (And if it would now be helpful for me to admit that mine was a crime of sorts, then I feel I must also be allowed to maintain that I did not deserve the punishment.) Rather, I seem to recall that I was trying to be as careful and as sensitive and as discreet as possible; it was William who was acting like a fool.

We had finally come to a halt in the middle of ‘The Desire for Order’. Lucy and Nathalie were somewhere up ahead – progressing unabashed through the room designated ‘Modern Life’. I had been hoping to slip away without detection. But matters were not proceeding to plan. For the last two minutes, William had been following me through the gallery with the air of a pantomime detective: two steps behind, stopping only a slapstick fraction after me, and then raking his eyes accusingly up and down my person as if I were responsible for the summary immolation of an entire pension of pensioners or some such outrage.

He spoke in a vociferous whisper: ‘Jasper, what – in the name of arse – are you doing?’

‘Ssshh.’ The artificial lights hummed. ‘I am attempting to enjoy my birthday.’

‘Well, why do you keep running away from us?’

‘I’m not.’

‘Of course you are.’ His voice was becoming progressively louder. ‘You are deliberately refusing to enter “Modern Life” – over there.’ He pointed. ‘And you keep drifting back into “the Desire for Order” – in here.’ He pointed again, but this time at his feet and with a flourish. ‘Don’t think I haven’t been watching you.’

‘For Christ’s sake William, if you must know –’

‘I must.’

‘I am trying to get off this floor altogether and back upstairs into “Nude Action Body” without anybody noticing. So it would be very helpful if you would stop drawing attention to us and go and catch up with the girls. Why, exactly, are you following me?’

‘Because you’ve got the booze and I think you should open it. Immediately.’ He paused to draw a stiffening breath. ‘And because you always look oddly attractive when you are up to something.’

‘I’m not up to anything and I haven’t got the wine: I stowed it inside Lucy’s bag, which is now safely inside a cloakroom locker.’ I feigned interest in the mangled wire that we were facing.

‘You didn’t. My God. Well, we must mount a rescue. We must spring the noble prisoner from its vile cell straightaway! The Americans put their cream sodas in those lockers – I’ve seen them do it – and their … their bum bags. And God only knows what’s in Lucy’s bag: women’s products probably. And cheap Hungarian biros. You realize –’

‘Will you please keep your voice down?’ I frowned. An elderly couple wearing ‘I love Houston’ T-shirts seemed to be choking to death on the far side of the installation. ‘Anyway, Lucy uses an ink pen.’

But William was undeterred. ‘You realize that you may have ruined that great Burgundy’s life. One of the most elegant vintages of the last millennium traumatized beyond recovery within minutes of your having taken possession. It’s barbarous. I am holding you personally resp—’

‘William, for fuck’s sake. If you must talk so bloody loudly, then can you at least try to sound more like a human being from the present century? And less like a fucking ponce.’ I cleared my throat. ‘Besides, you’re not allowed to wander around Tate Modern swigging booze. It’s against the rules.’

‘Balls. What rules? That’s a 1990 Chambertin Clos de Bèze you’ve got locked up in there like a … like a common Chianti. Bought by me – especially for you, my dear Jasper, on this, the occasion of your twenty-ninth birthday. How could they stop us drinking it? They wouldn’t dare.’

I mimicked his ridiculous manner: ‘As well you know, my dear William, that bottle needs opening for at least two hours before we could even go near it. It’s my wine now and I forbid you to molest it before it’s had a chance to develop. Look at you, you’re slathering like a paedophile.’

‘Well, I think you’re being very unfair. You drag your friends out to look at all this – all this bric-à-brac and mutilated genitalia and then you deny us essential refreshment. Of course I am desperate. Of course I need a drink. This isn’t art, this is wreckage.’

I took a few steps away from him and turned to face a large canvas covered in heavy ridges of dun brown paint. William followed and did the same, tilting his head to one side in a parody of viewers of modern art the world over.

‘Actually,’ he said, a little less audibly, ‘I was meaning the small bottle of speciality vodka that Nathalie bought you. I thought you might have stashed it in your coat or something. I only need a painkiller to get me through the next room.’ Mock grievance now yielded to genuine curiosity: ‘Anyway, you haven’t answered my question.’

‘That’s because you are a complete penis, William.’

‘Why are you in such a hurry to leave us? What’s so special about “Nude Action Body”?’ He looked sideways at me but I kept my attention on the painting. ‘Is it that girl you were staring at?’

‘No.’

‘Yes, it is. It’s that girl from upstairs.’

‘No, it isn’t.’

‘The one you were pretending not to follow before we came down here.’ He paused. ‘I knew it. I knew it.’

‘OK. Yes. It is.’

He gave a theatrical sigh. ‘I thought you were supposed to be stopping all that. What was it you said?’ He composed his face as if to deliver Hamlet’s saddest soliloquy. ‘ “I can’t go on like this, Will, I am going mad. Oh Will, save me from the quagmire of womankind. No more of this relentless sex. Oh handsome Will, I have to stop. I must stop. I will be true.”’

I ignored him. ‘William, I need you to buy me some time and stop fucking around. Lucy and Nathalie will be back in here looking for us any second. Go and distract them. Be nice. Be selfless. Help me.’

He ignored me. ‘OK, maybe not the “handsome Will” bit – but those were more or less your words. And now look at you: you’re right back to where you were a year ago. You can’t leave your flat without trying to sleep with half of London. And never a moment’s cease to consider what the fuck you are doing or – heaven forbid – why.’

I walked towards the exit on the far side of the room and considered a collection of icons made to evoke the Russian Orthodox style. The figures were blurred and distorted and appeared to recede into their frames, so that it was impossible to tell whether they were indeed hallowed saints or grotesque contorted animals or merely half-smudged lines signifying nothing.

‘Look, Will, I need fifteen minutes. Will you keep an eye on the others for me – please? Don’t let them leave this floor. If they look like they’re moving, set off the fire alarm or something. I don’t want to fuck up and have to concoct some stupid bullshit. Not tonight. It would be awful. Lucy gets so uptight. I just want everyone to have as relaxed and pleasant a dinner as possible this evening.’

‘The fire alarm?’

‘Yes, it stops the escalators working.’

He shook his head, but there was amusement in his eyes.

‘I’m sorry. Will. But I swear to you: that girl winked at me and she is far too pretty for me to ignore. Admit it, she is. What am I supposed to do? I can’t just let it go. Come on. Millions of men would pay to be winked at by girls like her. I have a responsibility to act. Fifteen minutes max.’

He smiled. ‘Well, go on then: get on with it. But if the authorities arrest me for false alarms I shall instantly confess that you made me do it. I shall explain that you are dangerously persuasive and the worst sort of unscrupulous libertine –’

‘I’m exceptionally scrupulous.’

‘And I shall tell them that you are incapable of behaving in a decent manner towards friends – or even your own girlfriend – and that you deserve to be taught a serious lesson. See you in fifteen.’

‘Thank you, William.’

‘And don’t forget to check for sisters.’

Now, I don’t want to start blaming Cécile for the first wave of demoralizing set-backs that followed hard on the heels of this, the otherwise inauspicious evening of my twenty-ninth birthday, but as far as immediate causes of disaster go, then she has to shoulder full responsibility: J’accuse Cécile, la fille française. Had she not winked at me, I probably wouldn’t have risked it. But what could be the purpose of such fetching Mediterranean looks as hers, if not to fetch?

All the same, the fire alarm surprised everybody.

Chaos followed fast, rushing through ‘Nude Action Body’ like a messenger from the Front with news of approaching armies. From hidden antechambers and doors marked ‘private’ dozens of orange-clad ushers emerged and began urgently to usher; the lifts stopped; small blue lights flashed from odd places high on the walls; and (as if all this were not encouragement enough) an unnervingly measured female voice interrupted the revels every thirty seconds to spell the situation out in an exciting variety of languages. ‘This is a routine emergency. Please leave the building by the nearest fire exit and follow the advice of the officials. Thank you.’

I had only just returned to the fifth floor and had taken no more than three steps into the gallery proper. But now I doubled back and stood to one side by the wide emergency exit doors at the top of the escalators, waiting for Cécile. Along with everyone else, she was sure to leave this way. There was no longer any need to seek her. And I was rather enjoying all the panic.

Parents issued taut-voiced instructions to their charges. Scandinavians strode calmly towards the emergency stairs. Italian men put their arms around Italian women. A litter of art-college day-outers roused themselves reluctantly from their beanbags. Two children came careering out of ‘Staging Discord’ opposite. And an American woman began to scream ‘oh my God, oh my God’.

Given that Irony and Futility still seemed to be filling in for God and Beauty on the art circuit – the thought occurred to me that had I been filming the whole thing, I could perhaps have submitted the results for exhibition myself; perhaps a showing in ‘History Memory Society’: ‘People from All Over the World Leaving in Uncertainty’ (Jasper Jackson, calligrapher and video artist).

Of course I didn’t actually know that Cécile’s name was Cécile as I fell into place three or four people behind her. (Jostle, jockey, joke and jostle all the way down six flights of unapologetically functional fire stairs.) I didn’t know anything about her at all, except that she had short, choppy, boyish, black hair, a cute denim skirt cut above the knee, thin brown bare legs and unseasonable flip-flops, which flapped on every step as she went. And that she had (quite definitely) winked at me as we circled Rodin’s Kiss.

Outside, safely asquare the paving slabs of the South Bank, I looked hastily around. The light was thickening. St Paul’s across the Thames – a fat bishop boxed in and stranded flat on his back – and two bloated seagulls, making heavy weather of the homeward journey upstream. Crowds continued to eddy from the building but there was as yet no sign of William or Nathalie or Lucy’s adorable light-brown bob. Still, I had to act quickly.

Cécile was standing with her back to me, looking across the river.

‘Hi.’ I said.

She turned and then smiled, an elbow jutting out over the railings. ‘Oh, hello.’

‘That was quite exciting.’ I returned her smile.

‘You think there is a fire?’

I looked doubtful. ‘Probably terrorists or art protestors or rogue vegetarians.’

‘I wonder what they save from the flames?’ She bent an idle knee in my direction and swivelled her toe on the sole of her flip-flops. ‘The paintings or the objets?’

‘Good question.’

‘Maybe in an emergency they have an order for what to keep – and they begin at the top and then descend until everything is burning too much.’

‘Or maybe,’ I said, ‘they just let the bastard go until it’s finished so that they can open up afterwards as a new sort of gallery: Burnt Modern. A new kind of art.’

‘Perhaps that’s what the protesters want – a new kind of art.’ She was a born flirt.

I met her eye and moved us on. ‘They evacuated the building very quickly.’

‘Yes. But there are some people still coming out, I think.’ She gestured. ‘I like how in an emergency everybody starts to talk. As if because there is a disaster, now we can all be friends happy together.’ She looked past me for a second. ‘Will they let us back in, do you think?’

‘I’m not sure. But I am supposed to be going to a restaurant at eight so I don’t think I will be able to wait. This might take a couple of hours.’ I paused. ‘I should find my friends and see if they are OK.’

‘Me too. I have already lost them once today – when we were on the London Eye.’

‘How long are you in London for?’

‘I live here.’ She frowned slightly – amused disparagement.

I pretended to be embarrassed.

She relented. ‘I am teaching here.’

‘French?’

‘Yes.’ A pout masquerading as a smile.

‘You have an e-mail address?’

‘Yes.’

‘If I write to you, do you think that you’ll reply?’

‘Maybe. It depends what you say.’

I found William sitting on a bench with a diesel-coated pigeon and the man who had earlier been selling the Big Issue outside the main entrance.

‘Jasper – Ryan. Ryan – Jasper. We haven’t thought of a name for this little chap yet.’ He indicated the creature now pecking at a chocolate wrapper.

‘Where’s Lucy?’ I asked, acknowledging Ryan.

‘She’s fetching her bag with Nat. Did you meet anyone nice’ William winked exaggeratedly ‘– in the toilets?’

‘Yes, thanks.’

William did an American accent: ‘I hope you were real gentle with him.’

Ryan snorted and got up. ‘See you Thursday, Will mate,’ he said, ‘and let’s hope this new bloke knows how to deal with those fucking tambourine bastards.’

‘See you later.’ William raised an arm as Ryan left.

I sat down and was about to speak but William motioned me to be quiet.

‘Here they come,’ he said, ‘they’ve seen us.’

Lucy and Nathalie were making their way towards the bench. William addressed the pigeon: ‘You’ll have to piss off now, old chap, but we’ll catch up again soon, I hope. Let me know how the diet works out.’

Before we go much further, I should explain that William is one of my firmest friends from the freezing Fenland days of my tertiary education. (Philosophy, I’m afraid, man’s most defiant folly.) I can still remember the pale afternoon, a week or so after we had all arrived for our first year, when we were walking back from a betting shop together and he came out to me. It was going to be very awkward, he confided, and he was at a bit of a dead end with the whole idea because – apart from his sister, who didn’t count – he hadn’t really met any women before now, but – how could he put this?– he was rather worried that he might not be homosexual and – as I seemed to be rather, well, in the know on the subject, as it were – had I any suggestions as to next steps vis-à-vis the ladies?

Unfortunately, several centuries in the highest ranks of government, church and army had left the men in his family quite unable to imagine women, let alone talk to them. Indeed, William suspected that he was the first male child in sixteen generations not to turn out gay. As I could imagine, this was a severe blow both to him and his lineage but he had tried it with other boys at school on several occasions and there was absolutely nothing doing. The truth of the matter was that he liked girls; and that was that. And as he was now nearing twenty, he rather felt that he should be getting on with it. Could I offer any pointers?

Naturally, things have moved on a good deal since then and these days Will is regularly trumpeted by various tedious publications as one of the most eligible men in London. He is an invaluable ally and well known on the doors of all good venues – early evening, private and exclusive as well as late night, public and squalid. I regret to say, however, that his approach remains erratic and hopelessly undisciplined. Though many women find him attractive, the execution of his actual seductions is not always the most appropriate. It is as if a strain of latent homosexuality bedevils his genes – like an over-attentive waiter at a business lunch.

All else aside, William is the most effortlessly charming man that anybody who meets him has ever met. He is also genuinely kind. And though he claims to feel terribly let down by the astonishing triviality of modern life, this is merely an intellectual arras behind which he chooses to conceal a rare species of idealism. He does not believe in God or mankind but he visits churches whenever he is abroad and runs a music charity for tramps.

On the subject of William’s relationship with Nathalie … Back in March, he claimed that it was purely platonic and I have to say that I think he was telling the truth. Under light questioning, he explained that it was only in this way that he could maintain the exclusivity of their intimacy since – of the few women who shared his bed from time to time – Nathalie was the only one with whom he was not having sex. They were therefore bound together by uncompromised affection and happily unable to cheat on one another. (She, too, I understood, was at complete liberty.) This approach, he confided, was an ingenious variation on the arrangement his forefathers had shared with their various wives since they had first come to prominence (under Edward II); dynastic obligations aside, they had kept sex resolutely outside of marriage, thereby removing all serious woes, threats and resentment from their lives.

A little before midnight, the birthday evening’s rightful enchaînement having been long re-established, Lucy and I were alone at last, intimately ensconced at the corner of the largest table in La Belle Epoque, my favourite French restaurant. We were considering the last of our dessert with a certain languid desire, and feeling about as happy as two young lovers can reasonably expect to feel in a London so beleaguered by medieval licensing laws. A little drunk perhaps, a little reckless with the cross-table kissing, a little laissez-faire with the last of the Latour; but undeniably at ease with one another and, well, having a good time. The bill was paid and my friends had all left – William and Nathalie among the last to go, along with Don, another university friend, over from New York, with his wife, Cal, and Pete, Don’s fashion-photographer brother, who had arrived with a beautiful Senegalese woman called Angel.

If pressed, the casual observer would probably have informed you that he was watching a boyfriend and girlfriend quietly canoodling while they awaited a final pair of espressos. If he was any good at description, this observer might have gone on to say that the woman was around twenty-eight, five-foot six or seven, slim, with dead straight, bobbed, light-brown hair, which – he might have further noticed – she had a habit of hooking behind her ears. Had he dashed over and stolen my chair while I visited the gents’, he would also have been able to tell you that her face was very slightly freckled, principally across the bridge of her nose, that she had thin lips (but a nice smile), that her eyes were a beseeching shade of green and that she liked to sit straight in her chair, cross her legs and loosen her right shoe so she could balance it, swinging a little, on her extended big toe. He might have rounded the whole thing off with some remarks about how – even now – England can still turn out these roses every once in a while. But at this stage we would surely have to dispute his claims to being casual and tell him to fuck off.

It is more or less true to say that back then, Lucy and I were more or less a year into it – our relationship, that is. I’m not sure why – these things happen …

Actually, I am sure why: because I liked Lucy very much. That is to say, I still like Lucy very much. Which is to say I have always liked Lucy very much. Lucy is the sort of woman who makes the human race worth the running. She’s not stupid or simpering, and she only laughs when something is funny. She’s intelligent and she knows her history. Yes, she can be cautious, but she’s quick-witted (a lawyer by profession) and she will smile when she sees she has won a point. Then she’ll pass on because she’s as sensitive to other people’s embarrassment as quicksilver to the temperature of a room. She keeps lists of things to do. She remembers what people have said, but doesn’t hold it against them. She seldom talks about her family. And she has no time for magazines or horoscopes. If you were sitting with us in some newly opened London eatery, privately wishing you had an ashtray for your cigarette, you might well find that she had discreetly nudged one to a place just by your elbow. Which is how we met.

Even so, it is with regret that I must add that Lucy is a nutcase. But I didn’t know that then. That all came later.

‘Close your eyes,’ she said, putting her finger to my lips for good measure.

I did as I was told and lowered my voice. ‘You haven’t organized a –’

‘Too late. It’s tough. I’ve got you a big cake with candles and all the waiters are going to join in with “Happy Birthday to You”, so you’ll just have to sit still and act appreciative.’

I heard the rustle of a bag and the stocky chink of espresso cups.

‘OK, open your eyes.’

A young waiter with a napkin over his shoulder hovered nearby – curious. A neatly wrapped present lay on the table.

Lucy smiled, infectiously. ‘Go ahead: guess.’

I leant across and kissed her.

‘Guess.’

‘Earrings?’

‘You wish.’

‘A gold locket with a picture of Princess Diana?’

‘Oh, go on, for God’s sake … open it.’

I undid her neat wrapping and unclasped the dark velvet case: a gentleman’s watch with a leather strap, three hands and Roman numerals. I held it carefully in my palm.

‘So now you have no excuses.’ Her eyes were full of delight. ‘You can never be late again.’

I felt that tug of gladness that you get when someone you care about is happy. ‘I won’t be late again, I promise,’ I said.

‘Not ever?’

‘Not for as long as the watch keeps time.’

‘It has a twenty-five-year guarantee.’

‘Well, that’s at least twenty-five years of me being on time then.’

On the face of it ‘Confined Love’ is one of John Donne’s more transparent poems: a man railing against the confinement of fidelity. Neither birds nor beasts are faithful, says his narrator, nor do they risk reprimand or sanctions when they lie abroad. Sun, moon and stars cast their light where they like, ships are not rigged to lie in harbours, nor houses built to be locked up … The metaphors are soon backed up nose to tail, honking their horns, like off-road vehicles in a downtown jam.

On the face of it, Donne, the young man about town, Master of the Revels at Lincoln’s Inn, seems to be striding robustly through his lines, booting the sanctimonious aside with a ribald rhythm and easy rhyme, on his way to wherever the next assignation happens to be. But actually, that’s not the point of the poem. That’s not what ‘Confined Love’ is about at all.