Читать книгу Boys' Book of Indian Warriors and Heroic Indian Women - Edwin L. Sabin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

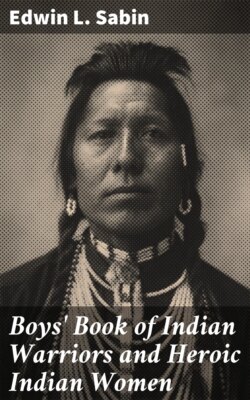

OPECHANCANOUGH, SACHEM OF THE PAMUNKEYS (1607-1644) WHO FOUGHT AT THE AGE OF ONE HUNDRED

ОглавлениеThe first English-speaking settlement that held fast in the United States was Jamestown, inland a short distance from the Chesapeake Bay coast of Virginia, in the country of the Great King Powatan.

The Powatans, of at least thirty tribes, in this 1607 owned eight thousand square miles and mustered almost three thousand warriors. They lived in a land rich with good soil, game and fish; the men were well formed, the women were comely, the children many.

But before the new settlers met King Powatan—whose title was sachem (chief) and whose real name was Wa-hun-so-na-cook—they met his brother O-pe-chan-can-ough, sachem of the Pamunkey tribe of the Powatan league.

A large, masterful man was Opechancanough, sachem of the Pamunkeys. The Indians themselves said that he was not a Powatan, nor any relation of their king; but that he came from the princely line of a great Southern nation, distant many leagues. This may be the reason that, although he was allied to Chief Powatan, he never joined him in friendship to the whites, who, he claimed, if not checked would over-run the Indians' hunting-grounds.

The Indians of Virginia did not wish to have the white men among them. They were living well and comfortably, before the white men came; after the white men came, with terrible weapons and huge appetites which they expected the Indians to fill, and a habit of claiming all creation, clouds veiled the sky of the Powatans, their corn-fields and their streams were no longer their own.

Powatan, the head sachem, collected guns and hatchets and planned to stem the tide while it was small. But these English enticed his daughter Pocahontas aboard a vessel, and there held her for the good behavior of her father.

Pocahontas married John Rolfe, an English gentleman of the colony. Now for the first time Powatan was won, for he loved his daughter and the honest treatment of her at English hands pleased him.

Opechancanough but bided his time, until 1622. He was a thorough hater; his weapons were treachery as well as open war; he had resolved never to give up his country to the stranger.

Meanwhile, Pocahontas had died, in 1617, aged about twenty-two, just when leaving England for a visit home.

Full of years and honors (for he had been a shrewd, noble-minded king) the sachem Powatan himself died in 1618, aged over three score and ten. His elder brother O-pi-tchi-pan became head sachem of the Powatan league. He was not of high character like the great chief's. Now Opechancanough soon sprang to the front, as champion of the nation.

Pocahontas was no longer a hostage, the English settlements and plantations had increased, the English in England were in numbers of the stars, and the leaves, and the sands; and something must be done at once.

Seventy-eight years of age he was, when he struck his blow. With the fierce Chick-a-hom-i-nies backing him, he had enlisted tribe after tribe among the Powatans. Yet never a word of the plan reached the colonists.

For several years peace had reigned in fair Virginia. The Indians were looked upon as only "a naked, timid people, who durst not stand the presenting of a staff in the manner of a firelock, in the hands of a woman"! "Firelocks" and modern arms they did lack, themselves, but Opechancanough, the old hater, had laid his plans to cover that.

March 22, 1622, was the date for the attack, which should "utterly extinguish the English settlements forever." Yet "forever" could not have been the hope of Opechancanough. Here in Virginia the white man's settlements had spread through five hundred miles, and on the north the Pilgrim Fathers had started another batch in the country of the Pokanokets.

The plan of Opechancanough succeeded perfectly. Keeping the date secret, tribe after tribe sent their warriors, to arrive at the borders of the Virginia settlements in the night of March 21.

"Although some of the detachments had to march from great distances, and through a continued forest, guided only by the stars and moon, no single instance of disorder or mistake is known to have happened. One by one they followed each other in profound silence, treading as nearly as possible in each other's steps, and adjusting the long grass and branches which they displaced. They halted at short distances from the settlements, and waited in death-like stillness for the signal of attack."

A number of Indians with whom the settlers were well acquainted had been doing spy work. It was quite the custom for Indians to eat breakfast in settlers' homes, and to sleep before the settlers' fire-places. In this manner the habits of every family upon the scattered plantations were known. There were Indians in the fields and in the houses and yards, pretending to be friendly, but preparing to strike.

The moment agreed upon arrived. Instantly the peaceful scene changed. Acting all together, the Indians in the open seized hatchet, ax, club and gun, whatever would answer the purpose, and killed. Some of the settlers had been decoyed into the timber; many fell on their own thresholds; and the majority died by their own weapons.

The bands in ambush rushed to take a hand. In one hour three hundred and forty-seven white men, women and children had been massacred. It was a black, black deed, but so Opechancanough had planned. Treachery was his only strength.

This spring a guerilla warfare was waged by both sides. Blood-hounds were trained to trail the Indians. Mastiffs were trained to pull them down. But the colonists needed crops; without planted fields they would starve. The governor proposed a peace, that both parties might plant their corn. When the corn in the Indians' fields had ripened, and was being gathered, the settlers made their treacherous attack, in turn. They killed without mercy, destroyed the Indians' supplies, and believed that they had slain Opechancanough.

There was much rejoicing, but Opechancanough still lived, in good health. He had been too clever for the trap.

Rarely seen, himself, by the settlers, he continued to direct the movements of his warriors. He refused to enter the settlements. Never yet had he visited Jamestown. Governors came and went, but Opechancanough remained, unyielding.

He was eighty-seven when, in 1630, a truce was patched up, that both sides might rest a little. So far the Indians had had somewhat the best of the fighting; the colonists had not driven them to a safe distance.

The white men were growing stronger, the red men were improving not at all, and Opechancanough knew that the truce would surely be broken. He stayed aloof nine years, waiting, while the colonists grew careless. At last they quarreled among themselves.

This was his chance. From the Chickahominies and the Pamunkeys the word was spread to the other tribes. The second of his plans ripened. Opechancanough had so aged that he was unable to walk. He set the day of April 18, 1644, as the time for the general attack. He ordered his warriors to bear him upon the field in a litter, at the head of five united tribes.

Again the vengeful league of the Powatans burst upon the settlers in Virginia. From the mouth of the James River back inland over a space of six hundred square miles, war ravaged for two days; three hundred and more settlers were killed, two hundred were made captives, homes and supplies were burned to ashes.

It looked as though nothing would stand before Opechancanough—indeed, as though the end of Virginia had come. But in the midst of the pillage the work suddenly was stopped, the victorious Indians fled and could not be rallied. They were frightened, it is said, by a bad sign in the sky.

Governor Sir William Berkeley called out every twentieth man and boy of the home-guard militia, and by horse and foot and dog pursued.

Next we may see the sachem Opechancanough, in his one hundredth year, borne hither-thither in his bough litter, by his warriors, directing them how to retreat, where to fight, and when to retreat again. He suffered severely from hunger and storm and long marches, until the bones ridged his flabby skin, he had lost all power over his muscles, and his eyelids had to be lifted with the fingers before he could gaze beyond them.

Governor Berkeley and a squadron of horsemen finally ran him down and captured him. They took him, by aid of his litter-bearers, to Jamestown.

He was a curious sight, for Jamestown. By orders of the governor, he was well treated, on account of his great age, and his courageous spirit. The governor planned to remove him to England, as token of the healthfulness of the Virginia climate.

But all this made little difference to Opechancanough. He had warred, and had lost; now he expected to be tortured and executed. He was so old and worn, and so stern in his pride of chiefship, that he did not care. He had been a sachem before the English arrived, and he was a sachem still. Nobody heard from his set lips one word of complaint, or fear, or pleading. Instead, he spoke haughtily. He rarely would permit his lids to be lifted, that he might look about him.

His faithful Indian servants waited upon him. One day a soldier of the guard wickedly shot him through the back.

The wound was mortal, but the old chief gave not a twinge; his seamed face remained as stern and firm as if of stone. He had resolved that his enemies should see in him a man.

Only when, toward the end, he heard a murmur and scuff of feet around him, did he arouse. He asked his nurses to lift his eyelids for him. This was done. He coldly surveyed the people who had crowded into the room to watch him die.

He managed to raise himself a little.

"Send in to me the governor," he demanded angrily.

Governor Berkeley entered.

"It is time," rebuked old Opechancanough. "For had it been my fortune to have taken Sir William Berkeley prisoner, I should not have exposed him as a show to my people."

Then Opechancanough died, a chief and an enemy to the last.