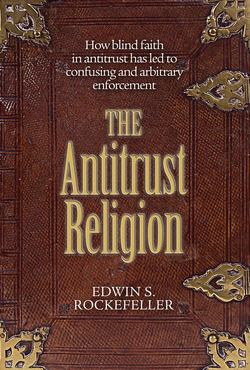

Читать книгу The Antitrust Religion - Edwin S. Rockefeller - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. What Is “Antitrust”? Quasi-religious Faith Distinct from the Antitrust Statutes

ОглавлениеSection 4 of the Clayton Act of 1914 provides that any person “injured in his business or property by reason of anything forbidden in the antitrust laws” may sue for three times his damages plus costs and “a reasonable attorney’s fee.” Section 1 of the Clayton Act defines the term “antitrust laws” as including the Sherman Act of 1890 and the Clayton Act. These are referred to in this book as “the antitrust statutes.” Definitions are important for making sense of the subject. The antitrust literature provides little help. Most of it perpetuates confusion. Consider the following example from a basic textbook used at the Harvard Law School:

Antitrust law implicitly but clearly takes a particular stance toward the economic problems to which it applies. On one hand, its very enactment indicates that Congress rejected the belief that market forces are sufficiently strong, self-correcting, and well-directed to guarantee the results that perfect competition would bring. On the other hand, antitrust’s domain is intrinsically limited.1

What are the authors talking about? Antitrust law? Antitrust? The antitrust statutes? Do they recognize any difference among those three terms? There are two antitrust statutes, the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act, adopted by Congress and found in the U.S. Code. You can look them up. The quoted passage does not refer to those statutes but begins with the undefined term “antitrust law,” which implies a coherent set of rules that “takes a particular stance.” The student is told that enactment of “antitrust law” shows that Congress rejected a belief that the market is self-correcting. But Congress did not enact “antitrust law.” It enacted two antitrust statutes, one in 1890 and another in 1914. What beliefs Congress entertained or rejected at either of those times is debatable.

Next the student is introduced to an additional undefined term—“antitrust.” “Antitrust” has a “domain.” Authors Phillip Areeda and Louis Kaplow began with an imagined concept of “antitrust law” and then shifted to a discussion of “antitrust,” something different from “antitrust law” and even more distant from the antitrust statutes. Antitrust has an existence outside of the antitrust statutes. Antitrust not only exists but also does things. It is a formidable actor. The professors describe it thus:

Antitrust supplements or, perhaps, defines the rules of the game by which competition takes place. It thus assumes that market forces—guided by the limitations imposed by antitrust law—will produce good results or at least better results than any of the alternatives that largely abandon reliance on market forces. Therefore, the perfect competition model can be viewed as a central target, the results of which antitrust seeks, but the conditions for which antitrust does not take for granted. Antitrust thus looks to perfect competition for guidance, but the analysis inevitably emphasizes the myriad and complex imperfections of actual markets.2

Antitrust “supplements” or “defines.” The professors are not sure which. Antitrust “assumes” things. Antitrust “seeks results” but “does not take things for granted.” Antitrust “looks to perfect competition for guidance” to supplement the guidance that it has received from antitrust law’s limitations. Having extracted from the antitrust statutes an imagined concept of “antitrust law” and having pulled out of that hat a rabbit called “antitrust,” the professors conclude by telling us what “the analysis” emphasizes. The student might wonder: where did “the analysis” come from? The antitrust statutes? Antitrust law? Antitrust? Whose analysis is it? Why is it “the” analysis?

Antitrust is not defined in any of the provisions of the antitrust statutes. It can’t be translated into foreign languages. Antitrust was not enacted. It is not a coherent set of rules. You can’t look it up. Experts are required to interpret it. Much of it is in the eye of the professor. In their casebook, Eleanor Fox and Lawrence Sullivan write of “the central concern of antitrust” and its “several goals” and that “antitrust regulates economic structure and economic conduct through law.”3 They also tell us when a court decision is “a defeat for antitrust.”4 Timothy J. Muris, while chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, observed that there is much to do “to assure that antitrust avoids the mistakes of its past.”5

Antitrust can’t be amended, reformed, or repealed. It is an intuitive mix of law, economics, and politics; a mystical collection of aspirations, beliefs, suspicions, presumptions, and predictions. Antitrust is a quasi-religious faith independent of the provisions of the antitrust statutes.

Antitrust has many doctrines that are analyzed endlessly in lectures, seminars, articles, and court opinions. The antitrust faith is based on four elements that are seldom mentioned but will be discussed in subsequent chapters of this book. They are as follows: (1) a belief in the legend of Standard Oil, (2) fear of corporate consolidation, (3) a belief in the magic of “market power,” and (4) faith that government can protect us from those evils.