Читать книгу The Mark - Edyth Bulbring - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеDrudge School

Kitty scowls at the morning with bloodshot eyes. She stinks of bug juice.

The smell is a dead giveaway: she broke curfew last night and crossed the river without a pass to the pleasure clubs in Mangeria City. This is where she goes. I know, because I have followed her.

“If the Locusts catch you, you’ll be in for it. Or if Handler Xavier finds out he’ll give you a fat lip,” I say, glaring at her. “He says we must never do things to draw the Locusts’ attention to us.”

I hand her a piece of soap.

She lathers her skin and splashes herself with the water ration I had fetched from the outside tap. Rub-a-dub-dub. She likes to scrub her nights away. She soaps her left arm, underneath the bangles, rubbing the scar there pink and shiny.

“Oh, shut up and stop nagging,” Kitty says. “I can always dodge the Locusts at the booms, and there’s more than one way of crossing the river.” She snaps her fingers at me and I toss her a towel.

I am as familiar as Kitty is with the ways into Mangeria City after curfew. I have tracked her to the banks of the river after the sun has gone down. There, a hundred metres from the bridge, hidden among the dunes, groups of Scavvies wait with their seacraft. For just one credit, they take us across the river. But they do not promise to bring us back.

The Locusts patrol the river banks, and when they catch the Scavvies they beat them up and threaten to lock them away in Savage City. But mostly the Scavvies pay a bribe and go on their way.

“They’ll put you away in Section AR. You’re not old enough to go to the clubs,” I say. Section AR is the place for attitude readjustment, for kids with problems. There, they get sorted. And when they come out, they do not have any attitude at all.

Kitty holds her head in her hands. “Buzz off, Ettie. You make me sick. Just get off my back and mind your own business.”

When Kitty says things like this it makes my chest sore. But I must be hard on her. If I am not around to watch out for her she could get hurt.

I pass her a pair of shorts. Kitty and I are the same height, but she struggles to fasten the button around her belly. And her shirt strains over her chest, where mine sags.

She grabs the water from the table by the mattress and downs it, wiping her mouth with the back of her hand. She squeezes one of the mango balls. “It’s too squishy. Couldn’t you have done better?” But Little Miss Muffet eats it anyway.

Kitty talks with her mouth full. Greedy for the next bite. “I’ll graduate in a few months. Then I’ll be legal and can hang out there all the time when I’m working.” She spits a piece of plastic on the floor. So there.

I do not know what it is with Kitty and the pleasure clubs. Yes, I do, actually. It is the Posh and their credits. Especially the men. They are attracted to Kitty like the filth that is drawn to the banks of the river. Always looking at her. Stroking her. Calling her “pretty Kitty”. She likes this. I wish she did not. But it is what she has learnt at school.

Kitty guzzles the other mango ball while I cover my body with sunblocker. Protecting her skin is not something Kitty has to worry about too much. Her skin is the colour of roasted corn. She does not burn like me. I have Posh skin. Pus-coloured flesh.

There is a familiar whistle outside the door, and I let Handler Xavier in. He has plans for us today. I hope it is not more beach. My skin is raw from yesterday. Sometimes, if I hope for something hard enough, it happens. And other times I hope, but there’s nothing. It gets a bit tricky so I wear my don’t-care mask and wait for Handler Xavier to call the shots.

“We need to stay off the beaches for a couple of days. The monster scam worked lovely yesterday, but we can’t do it again soon,” he says.

One day people will get wise to it. They will realise that nothing lives in the sea. That the only monsters are the ones in our minds, growing fat on stories told by the Mangerians. Stories to keep us in the ghetto, away from the cities across the seas that survived the big drowning after the conflagration.

“Use this.” Handler Xavier hands me a tube of sunblocker. “The old stuff won’t protect you.”

It is not like he cares when I burn. But if people do not see my eyes he says I can pass for a Posh, and that could be useful in the game.

I smear the sunblocker on my face and arms. It smells of plastic. Everything smells of plastic in Slum City. When I breathe, I smell plastic. When I eat, I taste plastic. And when I sweat, my skin is coated with abnormally shiny beads.

“So, if it’s not the beach, what’s it going to be?” I am hoping it is the parade. Then, after gaming I can give the handler the slip and go to the Tree Museum. Let it be the parade. I hope so. No, I do not.

I love trees the way Kitty loves mangoes. There is a forest that survived the burnings, it is at the museum in Mangeria City. I used to save my credits and visit the museum and stroll among the trees, looking for the magic faraway tree. I had read about this tree when I was a lot younger. I did not know if it was still alive or if it had been chopped down in the olden days to boil someone a pot of soup. If it survived, though, I would recognise it.

I would find that tree and it would take me up the ladder to the place where Moonface and the Saucepan Man lived. I would disappear into the Land of Treats with Jo, Fanny and Bessie, and eat exploding toffees.

Lots of credits later, I still had not found the tree. When I stopped being a dead-brain, I realised that the magic faraway tree never was. Just a bunch of hocus in a book.

“We’re going to work the parade today,” Handler Xavier says.

Bingo!

“Kitty and I will handle the parade with a couple of the others, while you do school, Ettie.”

See, I said bingo too soon. It is my own fault for wanting it too badly. Handler Xavier searches my features. I give him my yippee-I’m-going-to-school face, even though school is hideous, right up there with flies and plastic. And even though I do not like Kitty gaming without me.

“But Kitty hasn’t done school for days now. They’re going to notice and ask questions.” I shake my head like this bothers me, as if I care about people sticking their noses too close to the game.

“I cleared it with the scholar warden last night. I told him Kitty’s down with sun sickness.” Handler Xavier sucks in my concerned face. “But it’s good that you’re being careful, Ettie. You’re sweet. A real team-player.”

As sweet as the plastic taste of sunblocker on my fingers.

Kitty wipes a wand over her eyelashes. She smoothes her hair and fixes it with the clip she has forgotten to thank me for. She gives the sliver of mirror a smile. One of the smiles she has learnt at school. It is a pretty trick that makes men look at her. It makes me want to smack her face. No, I do not. Of course, I never could.

The handler peers out the window. “It’s going to be a hot one today.”

Black clouds are massing on the horizon. But they do not signal rain. It only rains before the middle months. These clouds tell me a floater is coming. Burning slicks of oil from the olden days, which still haunt the seas.

Sometimes the wind drives the floaters back out to sea, but on calm days they stay close to shore, brooding, until the Scavvies brave the fires and drag them away. When the slicks lurk on the shoreline, the sky is dark for days, and you cannot tell if it is day or night. Except when the sun’s face burns a hole through the smoke.

I grab the nose shields from our box of possessions and give one to Kitty. It will not block the taste or allow us to breathe better. But it helps filter the poison and stops your nose clogging up.

I leave them both and fly off to school. I take the second star to the right, straight on till morning. I am on my way to Neverland with Wendy and Michael and John. Far below me, the taxis, packed with traders, cross the river to Mangeria City. I swoop over the taxi Pulaks, flying high to dodge the arrows of the Lost Boys. Higher than the trees in the museum. As high as the magic faraway tree, where Dame Washalot hangs out her huge panties before tossing the dirty water.

Dodge those arrows, Wendy. Dodge that soapy water, Jo, Fanny and Bessie. “Watch where you’re going,” a Pulak shouts. I step off the road and into a gutter full of muck. I clasp the shield over my nose and keep my eyes on the road as I trudge to school.

Children loiter outside the education centre and wait for the scholar warden and the teachers to arrive. I edge away from a group of girls leaping in and out of squares on the concrete. Standing outside the circle, I make myself invisible. The fewer people who see you, the less trouble they can cause for you.

“It’s Ettie Spaghetti,” a girl says. The other girls stop jumping and crowd around me, chanting. Their pinches tell me how much they like me.

I know why they do not like me. It is because I keep to myself. It is safer that way. Apart from Kitty, friends are not something I do. This is one of my rules. Not one of the set that Handler Xavier made me learn from day one in the game. It is a rule I have made for myself.

I figure there is only one person you can trust in the world: you. Someone has to be looking out for me one hundred percent. And I am the only one I trust to do this. If I do not survive, there will not be anyone around to look out for Kitty. And she is not strong enough to look after herself.

“Ettie Spaghetti,” the girls scream. They dance around and make cow eyes at me.

Tick-tick-tick. I wait for Captain Hook’s crocodile to come and chew off their hands. Instead, the scholar warden arrives with the teachers.

“Silence.” The warden whacks his cane on the ground and the noise dies. “Get to your lessons. Now.”

We disperse into our classrooms, according to our trades. The room for drudges like me is the largest in the education centre. We shuffle behind our desks, and I pick the peeling skin off my knees as we wait for the teacher to arrive. She will spend the day teaching us how to look after the homes and children of the Posh. This is going to be my trade when I turn fifteen.

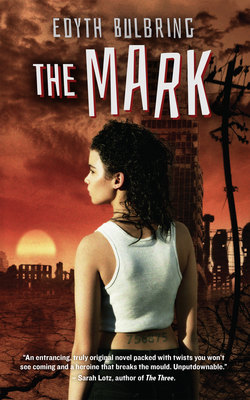

We are all assigned a trade at birth. Our trade numbers are spewed out by The Machine and branded on the back of our spines. You can scrub as much as you like and it never comes off. I know, because I have tried.

My trade is right down there in the gutter, with the Drainers who clean the streets. I should have grown used to it by now, I have known about my fate for nearly ten years. Ever since the day Kitty and I turned five, when the orphan warden packed us off for our first day at school.

We arrived together, but got separated after the scholar warden examined the marks on our backs.

Was it random? Or did The Machine somehow know Kitty would be beautiful and that I would have large hands rough enough to mop up dirt? The people who know things in Slum City could never give me the answer to this.

“You were born to serve as drudges. You will work for the Posh until you are of no further use,” the drudge teacher told us. “This is the trade that has been chosen for you.”

Everyone clapped and cheered. Not me. I held my claps in my fists and my tongue behind my teeth.

The drudge teacher is as old as my trees in the museum. She is retired from her trade and has been tasked by the Mangerians to prepare the next generation for their jobs. At the beginning of the day we are made to recite the drudge pledge.

“Louder,” she instructs, scrutinising our faces to make sure we are chanting the oath with pride: “I am proud to work in the homes of the Posh and to raise their children and clean their homes.”

Hiding my fury, I spit out the words.

Every morning we learn skills that equip us to work in a Posh home. Clean. Polish. Dust. In the middle of the day we are fed water boiled with the discarded plastic that wraps the vegetables in the market. The drudge teacher calls it soup. After eating, we practise what we have learnt. We wash the plates and clean the kitchen and the classrooms. Wash. Scrub. Sweep.

As I rinse the plates in the sink, the sounds of music and laughter from the pleasure workers’ classroom taunt me. There, the boys and girls learn how to serve drinks. How to dance and smile and amuse the Posh in the pleasure clubs. And how to treat themselves when they get sick.

In the yard outside, I hear the grunts of boys training to be taxi Pulaks. They are kneeling in the yard, tugging at ropes. The students have to stay there, in the sun, until one of them keels over.

“Pull together,” the Pulak teacher shouts at them.

Our afternoon classes are for child-rearing and serving etiquette. “When a Posh baby is hungry, what must you do?” the drudge teacher asks, pointing at a girl staring out of the window. The girl mumbles and the class gulps fetid air.

“Go to the scholar warden. He’ll help you learn your lesson today,” the teacher says.

When the girl returns, she ignores the chair behind her desk and chooses to stand. The lesson she learnt from the scholar warden is written in red marks on the backs of her legs.

“What must you do when a child cries?” demands the drudge teacher.

A boy at the front of the class raises his hand. “You must pick it up and soothe it,” he recites.

And pinch it when no one is looking and pull its hair.

The teacher looks at the boy, stretches her lips. “Yes, oh yes. And how must you serve the master of the house his soup?”

“You must make sure it is hot. But never too hot.”

And when he is not looking you must spit in the bowl.

The teacher glances at me. “Ettie, you’ve got something to add?”

I am one of her favourites. Teacher’s pet. I slap on my sincere and respectful mask. It must never slip. The backs of my legs were taught one lesson too many before I got smart and learnt that teachers’ pets don’t go to the scholar warden for special tutoring.

“When you serve the master of the house his soup you must not look at him but keep your eyes on the ground.”

And curse him under your breath.

The teacher claps her hands. The prints on her fingers and the lines on her palms have been worn smooth from scrubbing Posh floors. “Excellent, Ettie. I can see that you’re almost ready to serve in your trade.”

I smile at her. It makes my face hurt. Since learning of my future as a drudge I have tried to change it. Scrubbing the mark at the base of my spine with steel wool was the first thing I attempted. I was seven years old then. It left open sores on my back. The flies feasted on my flesh for weeks. When the skin healed, the numbers showed themselves again.

The next time, I applied some of the acid we drudges use to clean pots. It burnt my skin away. But when the scabs fell off, the numbers reappeared.

There are stories told by people who know things, stories about people who have tried to escape their trades by running away across the desert. But thirst always drives them back to the city, where they are caught again. They are tracked down by the Locusts who use the handsets linked to The Machine. No one knows precisely how it all works, but one thing is for sure – as long as those numbers are on our spines, there is nowhere to hide from the Locusts.

The day drags on, with nappies and teething and the correct way to cure indigestion (hold the brat upside down). My fellow trainees listen and suck it all in. Not me. I will never be a drudge. My fingers feel for the wound on my back. I have seen what the cream does to people’s skin. Another tube should do the trick. I must get another one fast. It is my last chance to get rid of my mark. The months will not stop their march towards my fifteenth birthday.

As the teacher closes her lips around the last syllable – “Drudge class dismissed” – I am out of the classroom and running.