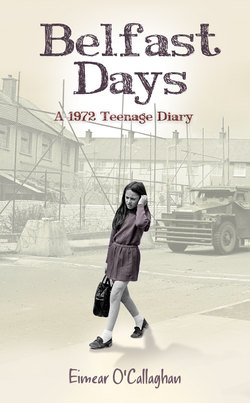

Читать книгу Belfast Days - Eimear O’Callaghan - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

‘Prayer is our only hope, seeing we haven’t got a gun!’

It was in June 2010 – just days before the British Prime Minister delivered the findings of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry – when I stumbled across my old diary, stuffed into a battered briefcase in a spare-room wardrobe. The spine of the journal was faded and frayed, its well-thumbed pages grown dull with the passage of time. The edges of the six glossy, paper butterflies which I pasted on to its cover as a teenager were beginning to curl up and crack, but their colour was as vivid as when they first caught my eye four decades earlier.

I was shocked by the terror which cried out at me from the squiggly handwriting on the page where my record of 1972 happened to fall open: ‘May 30 ... Came to bed convinced that prayer is our only hope, seeing we haven’t got a gun!’

The spidery, childish handwriting in faded blue ink stopped me in my tracks. What, in God’s name, was going on in my 16-year-old mind that made me even think about having a weapon? I couldn’t turn a gun on anyone, even if my life depended on it. Yet in West Belfast in 1972 – as a skinny, timid, Catholic teenager, with big, curly, ‘70s hair – I was confiding to my diary that prayer was the second-best option.

If we had been relying on my prayers to save us back then, God help us. I was just a month short of my seventeenth birthday when I penned that desperate entry in my red Collins notebook. I had seldom resorted to prayer except when pleading to St Joseph of Cupertino for help in my O-Level exams the previous summer:

O Great St Joseph of Cupertino, who while on earth did obtain from God the grace to be asked at your examination only the questions you knew, obtain for me a like favour in the examinations for which I am now preparing ... St Joseph of Cupertino, pray for us. Amen.

I was a sixth year pupil at St Dominic’s – Belfast’s largest Catholic girls’ grammar school – where academic success was all-important. My classmates and I used to pass the grubby, dog-eared prayer to St Joseph between us at exam-times – a picture of ‘the flying saint’ in religious ecstasy on one side, the miraculous prayer on the other – since part of the deal we agreed with the saint was ‘to make you known and cause you to be invoked ...’.

By the late spring of 1972, I would have made any deal God wanted so long as He protected us from the horror which began enveloping Northern Ireland after the Stormont government introduced internment the previous August. I said more prayers and made more promises to ‘the Man above’ in the first five months of 1972 than in all my previous sixteen and a half years. I kept on praying throughout the summer, into the autumn and all through the winter as violence escalated to a level which would remain unparalleled in the 30 years of ‘the Troubles’.

As curiosity subsequently lured me deeper into the diary, I sought out with interest my entry on Bloody Sunday, that awful day in January when members of 1st Battalion, the Parachute Regiment shot dead thirteen civil rights marchers in Derry. I turned back to the first page and embarked on a journey of rediscovery which would gradually explain my teenage desperation in over two hundred scribbled pages.

Notes from 1971: December 25th 1971

On looking back over the past year it is very difficult for anyone not to be filled with a great sense of sorrow, pity and failure. Sorrow, because of the great amount of damage and pain which has been brought to Northern Ireland during 1971 as a result of a long period of injustice and oppression, by a section of our community.

Pity for the families of those people who have lost their lives through shooting and bombing, and pity for the 500 families who spent this Christmas Day without fathers and brothers, because they have been imprisoned without trial in Long Kesh and Crumlin Road internment camps. Internment was introduced into this part of the United Kingdom by Brian Faulkner on August 9, 1971 and its results were tragic ...

By the time my O-Levels came around in the summer of 1971, Northern Ireland’s political foundations were shaking. The mainly nationalist clamour for civil rights, which first manifested itself on the streets in the late 1960s, had unnerved the unionist majority, leaving many of them fearful of being coerced into a United Ireland. Vicious sectarian clashes between Belfast’s Protestant and Catholic communities became commonplace. The British Army, which had been welcomed into Catholic areas in 1969, was by then the target of an increasingly ferocious IRA campaign – and met fire with fire.

Declaring in August that Northern Ireland was ‘quite simply at war with the terrorist’, the Unionist Prime Minister, Brian Faulkner, invoked the Special Powers Act and granted security forces the power to arrest and detain people indefinitely without trial. His decision to introduce internment proved to be disastrous, fanning the flames of republican aggression rather than quelling them. In the two years before detention without trial, fewer than 80 people were killed. By the time I started keeping my diary – just five months later – the death toll had risen to 230.

With growing bewilderment I started to read the pages of my rediscovered journal, some crammed with entries scribbled hastily in biro, others crafted neatly with my treasured Sheaffer fountain pen. I slowly began recalling the solitary hours I would spend filling out line after line in my eight-by-ten foot square bedroom. But the words and sentiments belonged to a person, place and time I no longer recognised.

On the first page, in the top left-hand corner, I had written ‘Received from Suzette, Christmas 1971’, alongside my name and address. My parents christened me, the eldest of their five children and their only daughter, with the ancient Irish name, Eimear. They loved the sound of it and its origins in the Celtic myths and legends associated with Cooley, my mother’s birthplace in the Republic.

The years have given me the confidence to appreciate and even be proud of my name but I can still feel, as though it was yesterday, how the colour would rise in my cheeks, and my mouth would start to dry, as I waited my turn to introduce myself to a group of strangers. Even with new teachers at the start of term in St. Dominic’s, the conversation was usually the same:

‘And what’s your name?’

‘Eimear.’

‘What a lovely name. How do you spell that?’

‘E-I-M-E-A-R.’

‘Really? I’ve never heard that one before. Eye-mere.’

‘No, Eimear. It rhymes with femur.’

‘Oh, sorry. Is it Irish? What does it mean?’

‘Yes, it’s Irish. But it doesn’t mean anything,’ I used to reply wearily.

My name did not translate into English but in Belfast in the early 70s, it did mean something: it marked me out as a Catholic. In a language and code peculiar to Northern Ireland, we labelled ourselves, and each other, with one tag or the other – Catholic or Protestant. When we met someone new, we circled each other cautiously, looking for ‘clues’ while trying not to reveal too much about ourselves, trying to work out which ‘camp’ they belonged to, which ‘foot’ they ‘kicked with’. A name, address or the school attended was enough to tell us whether a new acquaintance was ‘from the other side’ or was ‘one of us’.

Often as a young adult, growing up in such a divided society, I wished I had an ‘ordinary’ name, one that wasn’t so Irish, so Catholic and so difficult to spell. I wanted to be anonymous, like an ‘Anne’ or ‘Claire’ or ‘Christine’; anything that didn’t mean that I might as well have had the word ‘Catholic’ branded on my forehead.

... Ireland once had the reputation of being the ‘Land of Saints and Scholars’. This image is certainly far removed from the scene ... when passing through Belfast – a city full of soldiers, here to keep communities apart; bombed buildings; rows of burnt out houses and an air of fear and mistrust in every street.

As I read through my two-page introduction to the diary, its sometimes precocious tone and language embarrassed me. The memories, though, disturbed me. Belfast in 1972 was a dangerous place, where blending into the background and keeping out of harm’s way were the order of the day. Sectarian violence meant that no one, from either of our two communities, wanted to run the risk of being singled out for being different. If that meant that 16-year-olds like my friends and me kept to our own tiny patch in predominantly Catholic, nationalist Andersonstown – seldom venturing far beyond school, each other’s homes or occasionally the city centre – then so be it. The world we inhabited was, by necessity, small and familiar. But it provided us with relative safety.

The Fruithill Park home that I shared with my parents and four brothers was happy, loving and secure. During weekends and summer evenings, our long back garden, enclosed by hedges and trees, made a perfect playground, football pitch or battleground, depending on which and how many of my brothers and their friends were gathered there.

On Saturday afternoons, the smell of the home baking that my mother and I produced, working side by side, regularly filled our kitchen. The hammering or drilling from my father’s enthusiastic DIY efforts often competed with the racket made by the boys and our crazy mongrel dog, Tito. Homework routines were rigorously enforced around the kitchen and living room tables, despite protests from my brothers, and I willingly retreated to my bedroom to escape the happy mayhem.

My parents worked hard and were rightly proud of the comfortable, 1930s, semi-detached house they had saved for and bought when I was finishing primary school and Paul, the youngest, had just turned two. My father, who started his working life as a boy messenger with the Post Office many decades earlier, was well versed in Belfast’s unique religious and political geography and knew the areas where his young family was always likely to be safest. Even when the immediate and terrible consequences of internment were first inflicted on nationalist, working-class areas, our lives in quiet, residential Fruithill were initially normal and untroubled.

When I started to record the events of 1972, Paul was just seven and was inseparable from Jim who was three years older. Full of boyish devilment, they operated as a pair – ‘partners in crime’ – as did the two older boys, Aidan who was twelve and John, fourteen. All of them were still children when the ‘excitement’ of the Troubles exploded into our lives.

As the eldest of the five and an only girl, I enjoyed the privilege of having one of our four bedrooms to myself. I would spend hours holed up in that small room. My parents, Maura and Jim, would rap on my door to tell me I couldn’t possibly be studying properly, as my precious transistor blared out Radio 1 chart hits: Donny Osmond, all hair and American teeth, singing ‘Puppy Love’; David Cassidy asking ‘Could It Be Forever’; and ‘Telegram Sam’, ‘Jeepster’ and ‘Metal Guru’. What a great year that was for my favourites – the exotic, glam rockers, T Rex. At night, snuggled up in my narrow single bed, I would try to fall asleep as Radio Luxembourg DJs, with their trans-Atlantic twangs, whispered to me from the radio hidden underneath my blankets.

Outside, on the streets of Belfast, the IRA carried out deadly attacks on British Army patrols with increasing regularity and detonated bombs in the city centre with devastating consequences; soldiers killed members of IRA ‘active service units’, as well as innocent, unarmed civilians and people allegedly ‘acting suspiciously’; sectarian threats and attacks drove families out of their homes, while loyalists abducted and killed random workmen, students and late-night drinkers, just because they were Catholics.

Closeted in my bedroom at the back of the house, I took refuge in music, books and in the pages of the teenage magazine, Jackie, with its insights into make-up, fashion, celebrity and, of course, boys. I treasured the pull-out posters of idols like David Cassidy and Marc Bolan, while problem pages opened up a fascinating, new, forbidden world: ‘Dear Cathy and Claire, I think my boyfriend ...’; ‘Dear Cathy and Claire, what should I do ...’.

A sharp crack of gunfire or the sickening thud of a distant explosion would jolt me back to the reality of West Belfast. And so the depressing, anxious litany of questions and prayers would resume: ‘What was that?’ – ‘Where was it?’ – ‘Please God, don’t let anybody be killed.’ – ‘Please God don’t let it be anybody we know.’ The incessant ‘chuddering’ drone of army helicopters, circling above the rooftops, kept me awake at night. Their powerful, prying searchlights flooded my bedroom with light, casting distorted, ghostly shadows on the walls. Piercing whistles and the racket of metal bin-lids being banged on pavements alerted neighbourhoods to imminent army raids.

Again and again I wondered what it would be like to live in a ‘normal’ place – going out to discos and shopping with friends, free from the fear of bombs exploding; being able to rely on public transport for going to school – doing the things that ordinary teenagers did. The unexpected discovery of my long-forgotten diary, with its opening grim reminder of the autumn and winter of 1971, prompted me to revisit my ironically named ‘Happy Days’ scrapbook.

There, in black and white, were appalling images from the streets of Belfast: bare-handed rescuers searching in the dark, through the debris of McGurk’s bar after it was bombed by loyalists in December. A schoolgirl, two years younger than me, and a boy – who was even younger – were killed with thirteen other Catholics when the no-warning device exploded. Page after page carried photographs of buildings in flames, army machine-gun posts, bewildered business owners staring in disbelief at the ruins of their livelihoods, and soldiers uncoiling huge rolls of barbed wire to cordon off streets and keep neighbours apart.

I had collected accounts of interrogation and torture written by men interned in Long Kesh since August 1971, as well as a selection of the simple black-and-white Christmas cards they made for their families and friends on ‘the outside’. I covered two full pages with a black-and-white photograph that I cut out of the Belfast Telegraph, showing 173 tiny white crosses planted in a wintry field, under the grim heading ‘And So Ends ‘71’.

At Midnight Mass in 1971, and for nearly thirty years afterwards, priests asked us to pray for everyone who had been killed in the violence of the previous twelve months and for everyone who was separated from their families at Christmas. We all bowed our heads and said our prayers; but secretly, year after year, I prayed selfishly and most fervently that my family and friends would stay safe, and that it would all be over soon. The last lines of my ‘Notes from 1971‘ entry reminded me of the bleakness of that Christmas:

This Christmas Day was celebrated by the internees with a hunger-strike, by people in Andersonstown keeping a 24-hour fast outside the church, by 4,000 people who gave up their homes on Christmas Day to defy the army and to walk 10 miles to Long Kesh – and by 14,000 British soldiers, separated from their families to keep a riot-torn city at peace, for as long as is possible here.

Not long after my sixteenth birthday, and within weeks of internment being introduced, I made up my mind that I was going to ‘break out of it all’ and get a taste – if only for a month or so – of the world I glimpsed through the pages of Jackie. I wanted to go somewhere bright, sunny and normal; somewhere with no explosions, no bomb scares and no one getting shot. Neither I nor anyone in my family had ever been on a plane or gone to a country where English wasn’t the first language but that didn’t deter me; if anything, it encouraged and excited me.

When my friend Suzette, who was a student nurse and lived nearby, presented me with a new diary for Christmas, I resolved to be faithful to it. I looked forward to 1972 being my year: I would turn 17, get a part-time job, be transformed from an ugly duckling into a beautiful swan and finally find romance, travel and a promising new future.

End-of-year news programmes reminded us sombrely that 150 people had died violently since internment was introduced five months earlier. Naïvely, though, and with the optimism of a schoolgirl who had nobody belonging to her killed or in jail, I was convinced that Northern Ireland would soon settle down and the bloodshed stop.

Even in the bleakest moments of the autumn and winter of 1971, I could not have envisaged the violent depths into which our society was about to plunge headlong. I could not have foreseen the catastrophic repercussions of events like Bloody Sunday. In my political ignorance, I would never have dreamed that within a few months the Unionist-controlled Northern Ireland Government would be replaced with Direct Rule by the British Government at Westminster.

I stayed true to my diary, however, and recorded diligently, with just a few exceptions, my days and nights during what turned out to be the bloodiest year of Northern Ireland’s notorious Troubles. The account I unearthed after almost 40 years is not a history: it is the diary of a 16-year-old schoolgirl, woven through with her teenage hopes and fears. The savagery it evokes shocks and appals me, as does its evidence of how speedily and easily a society can violently implode.

It teaches me that the passage of time may soften the stark images and dull the strident sounds of our violent history. It can allow the ‘truth’ about our past to be distorted. My diary, though, is unsparing. With its brutal candour, it has proved more trustworthy than memory.