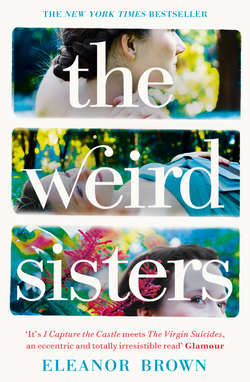

Читать книгу The Weird Sisters - Eleanor Brown, Элеонора Браун - Страница 6

ОглавлениеPrologue

We came home because we were failures. We wouldn’t admit that, of course, not at first, not to ourselves, and certainly not to anyone else. We said we came home because our mother was ill, because we needed a break, a momentary pause before setting off for the Next Big Thing. But the truth was, we had failed, and rather than let anyone else know, we crafted careful excuses and alibis, and wrapped them around ourselves like a cloak to keep out the cold truth. The first stage: denial.

For Cordelia, the youngest, it began with the letters. They arrived the same day, though their contents were so different that she had to look back at the postmarks to see which one had been sent first. They seemed so simple, paper in her hands, vulnerable to rain, or fire, or incautious care, but she would not destroy them. These were the kind you save, folded into a memory box, to be opened years later with fingers against crackling age, heart pounding with the sick desire to be possessed by memory.

We should tell you what they said, and we will, because their contents affect everything that happened afterward, but we first have to explain how our family communicates, and to do that, we have to explain our family.

Oh, man.

Perhaps we had just better explain our father.

If you took a college course on Shakespeare, our father’s name might be resident in some dim corner of your mind, under layers of unused telephone numbers, forgotten dreams, and the words that never seem to make it to the tip of your tongue when you need them. Our father is Dr James Andreas, professor of English literature at Barnwell College, singular focus: The Immortal Bard.

The words that might come to mind to describe our father’s work are insufficient to convey to you what it is like to live with someone with such a singular preoccupation. Enthusiast, expert, obsessed – these words all thud hollow when faced with the sandstorm of Shakespeare in which we were raised. Sonnets were our nursery rhymes. The three of us were given advice and instruction in couplets; we were more likely to refer to a hated playmate as a ‘fat-kidneyed rascal’ than a jerk; we played under the tables at Christmas parties where phrases like ‘deconstructionist philosophy’ and ‘patriarchal mal -feasance’ drifted down through the heavy tablecloths with the carols.

And this only begins to describe it.

But it is enough for our purposes.

The first letter was from Rose: precise pen on thick vellum. From Romeo and Juliet; Cordy knew it at once. We met, we woo’d and made exchange of vow, I’ll tell thee as we pass; but this I pray, That thou consent to marry us to-day.

And now you will understand this was our oldest sister’s way of telling us that she was getting married.

The second was from our father. He communicates almost exclusively through pages copied from The Riverside Shakespeare. The pages are so heavily annotated with decades of thoughts, of interpretations, that we can barely make out the lines of text he highlights. But it matters not; we have been nursed and nurtured on the plays, and the slightest reminder brings the language back.

Come, let us go; and pray to all the gods/For our beloved mother in her pains. And this is how Cordy knew our mother had cancer. This is how she knew we had to come home.