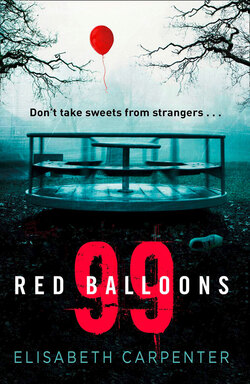

Читать книгу 99 Red Balloons - Elisabeth Carpenter - Страница 11

Chapter Six Maggie

ОглавлениеIt’s not Thursday, but I head to the newsagent’s anyway. I used to get the job papers for Sarah on Thursdays. She never looked at them much, mind. I just thought they’d give her a little push back into the world. The habit of buying them has stuck with me. I always leaf through them, seeing what jobs she might have liked, and ones she would tut and roll her eyes at. ‘As if, Mum,’ she’d say on a happier day. Catering – that had always been her thing. She’d wanted to be a chef since she was eight years old. It never happened though.

Anyway, why do I think about these things? It’s not even jobs day. At least I know I won’t bump into Sandra today.

It’s nearly the end of September; we only had a week of sun this year and that was in June. Now, it seems to be either raining, or just about to rain. It’s as cold inside the paper shop as it is out. Mrs Sharples is standing behind the counter, clad in about three jumpers, a quilted body warmer and fingerless gloves. I’m surprised the magazines and newspapers don’t blow away with that back door open. ‘Keeps my blood pumping,’ she says when people complain about the arctic temperature. She’s the type who’s grateful for waking up in the morning.

‘Morning, Maggie.’

She’s using that tone – what is it? I haven’t heard it in a while.

Pity.

Something must have happened. I wonder if she comments on bad news pertinent to every customer or reserves that honour for me. I scan the array of front pages. There it is. The Lincolnshire Gazette. It’s the only copy next to the many local papers bulging from the shelf. ‘Have to give the people what they want,’ Mrs Sharples usually says. It’s only Mr Goodwin who reads the Lincolnshire Gazette – it’s probably days old.

My head is telling me not to buy it – don’t give her the satisfaction – save the paper for Mr Goodwin. But my hands betray me. Before I know it, they’ve reached for the copy. I tut at myself. Predictable as night and bloody day. Oh well. Mr Goodwin won’t miss it – he doesn’t know what year it is, never mind what week.

‘Ah, you saw it then,’ she says.

I try not to roll my eyes at her.

‘What’s that?’

I hold the paper with both hands and look at the front page. Why am I play-acting? Mother said I’d never work on the stage with my hammy expressions. Mrs Sharples knows I’m pretending. I’m hoping my ruddy cheeks hide the blushes.

‘Oh yes,’ I say, anyway.

‘I do hope she’ll be found.’

‘Yes.’

Of course we hope she’ll be bloody found, I want to say, but I just fake a smile. As well as I can.

‘Must be terribly difficult for you to read articles like that,’ she says.

‘It’s difficult for anybody to read.’

‘I mean … Oh, never mind.’

She probably thinks she’s caught me on a bad day, though I’m hardly the laughing kind on the best of days. She gives me my change, her hands like little claws peeking from her fingerless gloves.

‘Apparently, the grandmother grew up in Preston.’

I look up from my purse.

‘Excuse me?’

‘The grandmother … of the little girl in the paper. I suppose you shouldn’t believe everything you read in the papers. Can’t say I’ve heard the name. Preston’s a big place after all.’

Her light laugh fades to a hum. She’s always been one for stating the flaming obvious.

‘Right you are, Mrs Sharples.’

I fold the paper and put it under my arm. I reach the threshold just as she shouts, ‘I’ve told you, Maggie. You can call me Rose. We’ve known each other long—’

‘Will do,’ I shout back.

But I won’t. Nosy old bat.

I lay the newspaper across the kitchen table, straightening out any creases. Ronnie used to like his paper ironed – fancied himself as one of those posh types. I only did it for him on Sundays, and his birthday. ‘It’s not because I like it straight,’ he’d say. ‘It stops the ink running.’

‘Get away with you,’ I said.

I wish he were still here with me. I’d iron it every day.

Oh, stop it, you daft fool. I can hear his voice in my head. You know you’d only iron it ’til the novelty of me being back wore off – two days, tops.

I sit down at the table. I’m daft having these conversations with myself, but after forty-six years of marriage I usually knew what he was going to say before he did.

Grace. That’s the little girl’s name.

She’s wearing her school uniform in the picture – it’s on the front page. I can’t make out the name of the school from the badge on her jumper, though I’m not sure if that’s my eyes or the quality of the print.

She was last seen walking into a newsagent’s.

Newsagent’s.

I look up at the wall. How odd. I wonder if she was getting sweets, just like—

The phone rings.

‘Hang on,’ I shout.

I shuffle the chair back and rest my hands on the table to lever myself up. Damn legs.

‘Wait a minute.’

I walk as fast as I can to the phone table in the living room. People can be so impatient these days. Some folk only let it ring five or six times before they give up. Never enough time for me.

‘Hello?’ I say. Ron always used to tease me about my telephone voice. ‘Hello?’ I can’t have been too late, there’s no dial tone. ‘Is anyone there?’

I listen as hard as I can. Is my hearing getting worse? There’s traffic noise on the other end of the line. Are they calling from a mobile telephone or a big red box?

‘Can you speak louder? I can’t hear you.’

The click of the phone makes me jump. They’ve hung up, again. I replace the handset and wander back into the kitchen. Was that the fourth or fifth time this week?

What if it’s him? I can’t remember what he sounds like; I should remember his voice, shouldn’t I? It’s been too long. Every day I try not to think about how he broke my heart. I can’t even look at his photograph any more without it bringing back awful memories.

Tap, tap, tap.

The window rattles.

I still my breathing. My heart’s thumping.

I should get up and hide in the pantry, but I can’t move.

The handle turns – the back door opens slowly.

‘Morning, Mags.’

I breathe again.

‘For goodness’ sake, Jim. I wish you’d warn me before just waltzing in.’

He takes off his cap.

‘That’s what the taps are for – they’re warning you I’m about to come through the door.’ He pulls out a chair. ‘Shall I whistle before I tap next time? A warning before the warning?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’

‘Anyway, it’s hardly the surprise of the century – I call round at least twice a week.’

I shake my head at him and flick the kettle on. He’s been coming round to check on me ever since Ron died. They’d been friends since they started working together over fifty years ago.

‘Though, Maggie, you looked as though you’d seen a ghost when I walked in.’ He looks around the kitchen. ‘I know you like to talk to yourself, but you haven’t actually seen anything, have you?’

I grab a tea towel off the kitchen counter and throw it at him. He holds out his hand and the towel drops into it.

‘You’d better watch yourself, Jim. One of these days it’ll land where it’s intended.’

‘I doubt that,’ he says, sinking slowly into the chair. ‘Bloody hell. My back’s getting worse. I can’t get comfortable these days.’

‘Watch your language.’

‘I’d rub my back if my arms could reach. Don’t suppose—’

‘Not on your life!’

‘Margaret,’ he says soberly. ‘If you’d care to let me finish. I don’t suppose you’ve got a hot water bottle handy?’

I ignore him. I’m not in the mood for tomfoolery. I turn my back on him as I make the tea. Do I tell him about the phone calls? He’d only worry if I did. They’re probably a wrong number anyway.

His ensuing silence must mean he’s seen the newspaper. He’s not even mentioned the leftover meat and potato pie on the kitchen counter. I can imagine what he’s thinking. Not again, Maggie.

I wait for it.

I place the pot of tea in the middle of the table and fetch over two cups, saucers, and the sugar bowl. He still hasn’t uttered a word.

‘Come on then,’ I say. ‘Out with it.’

He grabs three sugar cubes from the bowl with the tongs and drops them into his cup. Each one chimes as it rings against the porcelain.

‘I’m not saying a thing. Not after you got so upset last time.’

‘I wasn’t upset.’

‘Call it what you will, I offended you. I won’t be doing that again. Not on purpose at least.’

He turns the newspaper anti-clockwise. His eyes meet the little girl’s.

‘I hope they find her,’ he says, words I’ve heard for the second time today. I bet the parents have heard it a thousand times – if they’ve even ventured out of the house yet.

Maybe I should contact them, let them know they’re not alone – that I’ve felt like this, that I still feel like this? No. What comfort would that be? What hope would that offer if I still haven’t got Zoe back? I’ve sent a card to the parents of every missing child I’ve seen in the newspapers over the last three decades, giving my full name and address just in case they ever researched other cases. A simple Thinking of You card is usually fine. I never heard back from any of them though; I suppose they might’ve thought I was some sort of crank.

‘There’s always hope at the beginning,’ I say. ‘And she’s not been missing long.’

‘It’s the first twenty-four hours that are the most important, that’s what they say, isn’t it?’

‘I suppose.’

‘You know,’ he says. ‘I was thinking about what happened to our Vera. Remember I told you about her? She died in the Salford raids. She was only four years old.’

‘I remember.’

‘I didn’t hear about it from my mother of course. It was only after Mother died that my aunt Patricia told me about Vera. Fancy my mother and father keeping that to themselves all those years – just having to move on and get on with your life after your child dies.’

‘That’s what people did then, Jim. That’s what everyone did. It’s how everyone managed to get up in the morning. Death was all around us.’

‘It’s all different now,’ he says, looking down at the picture of the little girl.

‘And rightly so.’

The police didn’t even search the house when Zoe went missing – there certainly weren’t any helicopters.

Jim jumps slightly as the phone rings, but I don’t tease him about it.

‘Shall I get that for you?’ he says.

‘No. Let’s leave it. It’ll be a wrong number.’