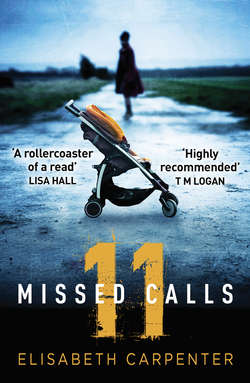

Читать книгу 11 Missed Calls: A gripping psychological thriller that will have you on the edge of your seat - Elisabeth Carpenter, Elisabeth Carpenter, Libby Carpenter - Страница 11

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеAnna

Sheila, the volunteer who comes in nearly every day, is in the back room of the bookshop, filling the kettle and sighing to herself. I don’t want to be here either. I need to be investigating the address that Debbie sent the email from.

It was at the end of primary school that I started the scrapbook filled with facts about her. I thought if I kept a list, then it would keep her alive – it was something tangible. As soon as I learned something new, I would write it down. There must be over a hundred snippets of information in there. Sometimes things would slip out of Dad or Robert’s mouth and I would repeat it again and again in my head till I could find a pen and paper. Grandad never said much about Debbie, though. I never had to carry a notebook when I went to his house. Perhaps he thought he was being kind.

Grandad usually comes into the bookshop on a Sunday after the ten o’clock Mass. He sits at the counter if he can wrestle Sheila out of the way. He said he wasn’t really into religion until Gran died nearly twenty years ago. He’s been to church every Sunday since.

My grandmother was sixty-nine when she had her first, fatal heart attack. I was ten, nearly eleven. She used to talk about my mother all the time. ‘I want you to remember all the little bits,’ she said, ‘in case I’m not around for long enough.’ It was as though she’d predicted her own death. She was the one who helped me create the scrapbook. ‘Your brother’s still too hurt to hear all of this. I don’t see that changing any time soon, Lord help him,’ she said. ‘But I’m glad you want to know. Frank can’t talk about her for long … He hides in his office.’

Grandad’s office is a little wooden shed he built in their back yard.

I wonder how he is taking the news about the note from Debbie. Dad must have told him by now, yet Grandad’s not answering his telephone or replying to his emails or texts. My messages are coming up as read, so I know he’s okay. But it’s not like him to ignore anything. He loves technology – he was the person who explained the workings of the Internet to me. ‘We are all closer together because of this,’ he said. ‘Though sometimes it makes us realise we’re worlds apart.’

The new volunteer is five minutes late. How can she expect to be taken seriously if she’s not punctual? She’s meant to be embarking on a new start. That’s what my boss, Isobel, said. I might be the manager of this bookshop, but sometimes Isobel sends volunteers here because she wants to appear more Christian than she really is.

At least it takes my mind off the letter for five minutes. Or rather, letters: plural. Why are different aspects of my life falling apart at exactly the same time? Can’t things go well for more than one day?

I put Jack’s letter back in his wallet last night, but only after I had taken a photo of it on my mobile phone. To the love of my life. That’s what she called him. It wasn’t dated, so I can’t tell if it is old or new. There were no references to any events past or present. I try to think back to when Jack and I got together, to remember names of past girlfriends, but I can’t. I don’t think we even mentioned our exes; it didn’t seem important once we found each other.

If the volunteer isn’t here in three minutes, I’ll look at the letter on my phone ag—

‘Annie Donnelly?’

I didn’t even hear the door open. A woman is standing in front of me. She is taller than me and in her late fifties, at a guess. She’s without make-up and her face looks weather-beaten and tanned, as though she spends her weekends outdoors. Her hair is dark, and her skin has a healthy glow that I will never have, being in this bookshop all the time.

‘It’s Anna,’ I say, a little more harshly than I intended.

I slide off the stool behind the counter.

‘Sorry.’ Her voice is quiet, but she returns my gaze. ‘I’m Ellen.’

‘It’s eight minutes past.’

I’m not usually so spiky, but already I get the impression she doesn’t want to be here. She glances at the clock behind me, then looks at her wrist.

‘My watch is behind … since the clocks went forward. I must’ve set it wrong.’

‘Right.’ I try not to waver from her gaze.

The clocks went forward nearly three months ago, but I don’t mention it.

‘Follow me into the back,’ I say, leading her into the small stockroom. Every spare space on the twenty-three long shelves is crammed with books.

‘I’ll get to my spot behind the counter,’ says Sheila, carrying her cup of tea.

‘Do you want to see my CV?’ asks Ellen, blinking so much now, it’s like there is something in her eyes. She reaches into her handbag before I reply, and hands me a brown envelope. ‘It sounds worse than it was.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘What they say I did. Did Isobel tell you?’

She means her criminal record. I’ve seen enough crime dramas to know that everyone says, I didn’t do it.

‘No. Isobel has this thing about confidentiality – she takes it seriously. If you want to tell me when you’re ready, then that’s up to you. As Isobel took it upon herself to get your references, you don’t have to tell me anything.’

I really want to ask what she was in prison for, but the words won’t come out. I’m the manager – I can’t engage in gossip.

‘Oh,’ says Ellen.

I’ve said too much, mentioning Isobel and her confidentiality, which I over exaggerated. She goes on about data protection, but she’s the biggest gossip I know.

We look at each other as I wait for Ellen to tell me all about it. She breaks my stare, looking instead at all the books on the shelves.

‘What do you want me to do?’ she says.

I try not to look disappointed – it might be on her CV. Though I doubt most people would count being in prison as an occupation.

I point to the table, which has three huge boxes of books on it.

‘These need sorting into categories and putting on the shelves, which are labelled with different genres, and fiction and non-fiction. Would you like a cup of tea first? My grandmother always used to say …’

I walk towards the kitchenette, not bothering to finish my sentence. Ellen’s already unpacking the books. I was boring myself anyway.

The sound of the kettle masks my opening her envelope. There is only one thing I want to check. If my mother were alive, she would be fifty-eight tomorrow. I look at the back of Ellen’s head. There is a photo of Robert in one of our old albums, where he’s gluing plane parts together; Debbie is sitting with her back to the camera – her long dark hair is pulled into a bun, so it looks like it’s shorter. Ellen looks just like her from behind.

I peek at the top of her CV. I see it.

I read it again to make sure.

Ellen has the same date of birth as my mother.

Sheila sniffs and remains on her perch behind the till.

‘I don’t have to go in the back if I don’t want to,’ she says. ‘If she wants to say hello, she’ll have to come in here.’ She leans forward. ‘She could be a murderess for all we know.’ She whispers as quietly as a church bell.

I could argue that Ellen probably isn’t a convicted killer, and that being the veteran volunteer of the bookshop with twelve years’ service, Sheila should make an effort to welcome her, but I don’t. It will fall on deaf ears, as things like this usually do with her – she pretends, at times convenient to her, that she’s hard of hearing.

Instead, I say, ‘How many people do you know that have the same birth date as you?’

It’s like I can hear the index cards sifting in her mind as her eyes drift away into the past.

‘Mavis Brierly,’ she says. ‘Fattest girl at school, though I don’t know how; no one had much money to buy so much food. After that, I met a woman in the maternity ward when I was expecting Timothy – can’t remember her name … began with a “C”, if I remember rightly. So, two people. Though they’re probably dead now. Most people I know are.’

I shouldn’t have asked her; I shouldn’t be thinking like this.

The last time it happened was six years ago. It was the woman who used to work in the bakery a few doors down from the shop I used to work in. If it hadn’t been for Jack, I’d have a restraining order against me.

‘Okay,’ I say. ‘So, it’s not as unusual as I thought.’

‘Obviously not. There are only three hundred and sixty-five days in a year, and millions of people in this world.’ She leans towards me again. ‘Why do you ask? Has Tenko in there got the same birthday as you?’

‘Sheila! You must stop talking like that. Everyone deserves a second chance.’

Ellen clears her throat. She’s standing at the doorway.

‘This book,’ she says. ‘I think it might be valuable. It’s a Harry Potter first edition.’

Sheila picks up a pen and writes on the notepad next to the till on the counter. She pushes it towards me when she’s finished. She’s probably a thief.

My face grows hot as I rip the sheet from the pad. I screw it up and drop it into the bin, before ushering Ellen back into the storeroom. She can’t have seen what Sheila wrote, but she will have noticed the whispering, and the silence that followed her presence.

‘I’m so sorry about that,’ I say, in case she read it. ‘I’ll give Sheila a warning. I don’t want you to feel uncomfortable.’

Ellen sits at the table and places the book in front of her.

‘It’s okay. I’m used to it,’ she says. ‘There was one person in particular who targeted me when I was inside: Jackie Annand. She never liked me. But that’s another life. I’m here now.’

She looks up at me and smiles. She has the same eyes as Sophie.