Читать книгу Marta - Eliza Orzeszkowa - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Grażyna J. Kozaczka

In her 1898 treatise, Women and Economics: A Study of the Economic Relation between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution, Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935), an American feminist writer and lecturer, clearly identified the differences between opportunities available to either young men or women entering adulthood:

To the young man confronting life the world lies wide. . . . What he wants to be, he may strive to be. What he wants to get, he may strive to get. . . .

To the young woman confronting life there is the same world beyond, there are the same human energies and human desires and ambition within. But all that she may wish to have, all that she may wish to do, must come through a single channel and a single choice. Wealth, power, social distinction, fame,—not only these, but home and happiness, reputation, ease and pleasure, her bread and butter,—all, must come to her through a small gold ring. This is a heavy pressure.1

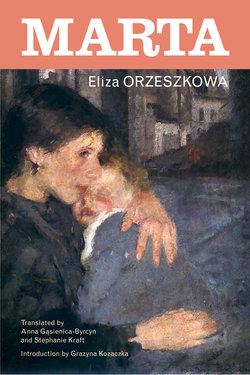

A quarter century earlier than Perkins Gilman, a Polish author and social reformer, Eliza Orzeszkowa (1841–1910), placed the same issue at the center of her early novel, Marta (1873), which tells a story of a twenty-four-year-old widow and mother who gradually learns that the lack of the “small gold ring” makes her economic situation untenable. Orzeszkowa’s assessment of the condition of women in late-nineteenth-century patriarchal Poland is just as powerful as are the views expressed by Perkins Gilman. Orzeszkowa writes:

[A] woman is not a human being, a woman is an object. . . . A woman is a zero if a man does not stand next to her as a completive number. . . . If she does not find someone to buy her, or if she loses him, she is covered with the rust of perpetual suffering and the taint of misery without remedy. She becomes a zero again, but a zero gaunt from hunger, trembling with cold, tearing at rags in a useless attempt to carry on and improve her lot. . . . There is no happiness for her or bread without a man.2

In her novel, Orzeszkowa argues for women’s right to economic freedom, to successful and productive lives, to useful and serious education, and to equal employment opportunities. She extols the value of work not only as a means of financial support but also as a means of developing and strengthening character. Marta becomes Orzeszkowa’s social manifesto. It is a novel of purpose that advances the author’s worldview and illustrates it pointedly both with direct authorial commentary and with the story of her eponymous protagonist. This authorial commentary could seem heavy handed at times if it did not testify to the young author’s deep engagement in and her passion for the topic. Even before the publication of Marta, Orzeszkowa came out with a pamphlet, “Kilka słów o kobietach” (A few words about women) (1870), in which she advocated for sensible education of girls that would prepare them not only for a domestic role as a wife and mother but also for a possible career in the public sphere. Edmund Jankowski in his monograph about Eliza Orzeszkowa argues convincingly that this pamphlet together with Marta placed the author in the forefront of the feminist movement in Poland and won her fame.3

Orzeszkowa’s early life gave little indication of her later espousal of feminist views, fairly radical for traditional Polish society of the early 1870s. She spent her childhood on her father’s estate in Milikowszczyzna near Grodno in eastern Poland.4 Even though her father died when she was only a toddler, his death did not substantively change the family’s lifestyle, which was typical of a landed gentry home at the time. Both she and her older sister were educated at home by Polish and foreign-born live-in tutors. In her memoirs, she remembered fondly a Polish teacher who instilled in her and her sister great love for Polish literature and history, but also recalled their intense dislike for a German nanny. Eliza, obviously a precocious child, could not remember a time when she was not able to read both in Polish and in French. She entertained her frequently ailing sister with her own original tales and at the age of seven, she wrote her first novel—a melodrama of crime and guilt. But soon everything changed. By the time she turned ten, her sister died and she was sent to a boarding school in Warsaw where she would spend the next five years. Soon after finishing her formal education, seventeen-year-old Eliza married Piotr Orzeszko, a man twice her age, who owned a neighboring estate. Her own assessment of this period in her life was quite harsh. She wrote, “I was thoughtless and irresponsible. . . . I was nothing but vanity. I was delighted with my beautifully furnished and decorated home, with my clothes, servants, constant visits from friends and young neighbors.”5 Yet it was also then that under the tutelage of several well-educated acquaintances, she began a slow process of self-education by reading voraciously. Her favorite books included classic works of French and Polish literature as well as English Romantics in French translation. She also rediscovered her passion for writing. However, this intense project of self-improvement had for Orzeszkowa some unanticipated results. Within only a couple of years of her marriage, even before she turned twenty, she realized that the lack of any intellectual or emotional connection to her husband made her deeply unhappy. Even though she understood very well that marriage protected her from financial concerns and secured for her a solid social position, she began to consider filing for divorce. What she possibly did not anticipate was that freeing herself from this failed relationship would take many years, would cost her a fortune in high legal expenses, and would expose her to considerable social censure.

Marta, one of Orzeszkowa’s early works, is certainly a novel of its times as well as an indirect reflection of the author’s life. She chose her protagonist carefully from the ranks of the landed gentry. She understood this class well and knew that many, like herself, were struggling at this difficult time in Polish national and social history. In 1795, almost eighty years before Orzeszkowa published her novel, Poland ceased to exist as an independent country and was partitioned by and absorbed into the three neighboring empires: Russia, Prussia, and Austria.6 Yet Polish patriots, many of whom hailed from the landed gentry, never accepted the status quo. They continued to fight for the country’s independence militarily through armed uprisings as well as culturally through numerous efforts to preserve Polish national identity when language and culture were threatened by the anti-Polish policies of the occupying powers. Orzeszkowa herself became actively involved in the tragic January Uprising of 1863/64 that erupted in the Russian-controlled territory of Poland.

The mid-nineteenth-century political crisis in the Russian empire rekindled Polish hopes for regaining independence. Polish patriots organized numerous clandestine networks in the Russian-controlled Congress Kingdom of Poland (1815–67)7 with its capital in Warsaw. The sole purpose of such organizations was to fight for freedom and liberate Poland from foreign domination. Beginning in 1860, a series of patriotic street demonstrations erupted in Warsaw and continued into the following year, when in February marchers were attacked and shot at by Russian troops. The funerals of the five fatally shot demonstrators became a spark for further patriotic actions. The Russian-appointed governor of the Congress Kingdom, concerned about the volatility of the situation, planned to preempt any organized Polish insurrection by announcing conscription to the tsarist army. Such forced military service would cripple the conspirators by removing all able-bodied Polish young men from their ranks. This decision achieved the opposite effect, forcing Polish underground organizations to call Poles to arms and announce on January 22, 1863, the commencement of a Polish armed uprising against Russia.

For more than a year and a half, Polish insurrectionists fought the Russian army.8 Unfortunately, even with the support of their compatriots from the other two partitions as well as help from Polish émigrés abroad, they were not able to construct a regular Polish army and defeat the Russians. Polish volunteer forces were outnumbered approximately two to one by the regular Russian army. The January Uprising was a valiant patriotic effort that mobilized the entire society, as both men and women of all classes bore arms. The Jewish population also joined in this military effort. In addition, the revolutionaries were supported by an even larger number of Poles in noncombatant roles who helped by supplying food and clothing for the soldiers, caring for the wounded, and burying the dead. Unfortunately, in the end Polish volunteer forces succumbed to the regular Russian army. In addition to the casualties incurred during the heroic but often hopeless battles, the Russian reprisals after the defeat of the uprising further devastated the country and exposed its population to redoubled Russification efforts. This led many Poles to reconsider the value of armed resistance in the existing geopolitical situation and to shift their goals. Rebuilding Poland’s economy, strengthening its social structures, and preserving Polish culture became their premier objectives.

In her memoirs published posthumously in book form as O sobie (About myself, 1970), Orzeszkowa considered the effects of the trauma of the failed January Uprising on her and her generation. She described herself as a twenty-year-old witness to a national and social catastrophe:

I saw houses, which until recently brimmed with energy and activity, become swept clean of all signs of life as if during some deadly medieval plague. Deep in the woods, I saw mass graves hiding corpses of young men with whom I had so recently danced. I saw gallows, fear in the faces of the condemned . . . and the long lines of shackled prisoners on their way to Siberian exile being followed by their despairing families.9

Orzeszkowa understood very well that this national tragedy shook Polish social structure as well as gender balance. Thousands of women—wives, mothers, daughters, sisters, and fiancées of the fallen or imprisoned heroes whose estates were confiscated by the occupying government—were reduced to poverty and left without means of support. The women, who had been trained exclusively for the domestic sphere, suddenly found themselves forced to seek employment for which they were sadly unprepared. In Orzeszkowa’s novel, even though Marta loses her husband to an illness and not to the armed struggle, she shares the fate of these desperate genteel women whom she encounters in employment agencies and in garment sweatshops.

The immediate aftermath of the January Uprising marked also a personal turning point for Orzeszkowa and contributed to the development of her writing career. She invested heavily in this patriotic enterprise of Polish independence. She served the military cause by taking up the important and very dangerous job of a courier responsible for securing lines of communication between different clandestine cells. Understandably, after the failure of the uprising, her despair at the scope of the national tragedy and the realization of the hopelessness of the political situation led her to reassess her own life and mission in society. Even though she was spared punitive measures for her active participation in the uprising, her husband was sentenced to exile to a penal colony in Siberia. In a rash decision that she would regret for the rest of her life, she refused to follow him into exile and would eventually divorce him. She did not love Piotr, and as she explained later, she did not know then that she should have sacrificed her own happiness in order to support the man who suffered for Poland.

With her husband in exile, Orzeszkowa quickly learned about financial difficulties. The expensive and lengthy divorce proceedings cost her the estate she inherited from her parents. Even the personal happiness she dreamt of appeared elusive. Her romantic relationship with Dr. Zbigniew Święcicki became impossible due to social pressure. Such a complicated personal life increased her sensitivity to the situation of single women in a society that neither respected nor provided a safety net for them. Likewise, she gained awareness of the constraints placed specifically on women of her social class and learned of the price women paid for breaking social rules and taboos. She, like her protagonist Marta, desired to work in order to support herself. She wrote in her memoirs that she dreamt of becoming a teacher or possibly a telegraph operator in Warsaw, the capital of Poland then under Russian occupation. Her fluency in several languages qualified her for a job at the telegraph office, yet her application was rejected because she was Polish. She recorded in her memoir, “After I returned home, every memory of this humiliation caused me to shake with anger. How was it possible that in Warsaw, we Polish women had no right to work.”10 She explained that at the time her attempts to find employment were not particularly rooted in the emancipation ideology, but instead were necessitated by economic reality. As a divorced woman without a steady income from a landed estate, she needed to work just to survive.

The ideological awareness came a little later, especially after the publication of Marta, when the reaction of her female readers made her realize that she had hit a nerve. The fictional situation of her protagonist was a reality for thousands of Polish genteel women, whose lives had been changed by the loss of estates due to punitive confiscation or poor management in the changing economy and who suddenly found themselves, like Marta, needing to earn a living. Orzeszkowa wrote,

For the first time I began receiving letters from women who were strangers, belonged to different social circles, were of different ages and talents, but they were all thanking me for this book and asking me for practical advice. Many readers told me that they reacted emotionally to this novel and became extremely fearful about their own future. Many began to seek education and work.11

Orzeszkowa’s novel about a young Polish widow resonated with many women all across Europe. Shortly after its publication, Marta was translated into several languages including Russian, German, Czech, Swedish, Dutch, and even Esperanto.12

Eliza Orzeszkowa selected the city of Warsaw13 as the setting of her novel probably as a response to the social changes she observed, and especially to the growth of middle-class culture. She knew the city from the time she attended boarding school there. However, since the school was run by a women’s religious order exclusively for the daughters of the landed gentry, students probably had limited opportunities to explore the entire city and very few occasions to interact with its inhabitants. Yet it was in Warsaw that Orzeszkowa solidified her devotion to Polish freedom and her involvement with the issues of social justice. The early 1860s marked significant political, social, and economic upheaval in Warsaw and in the entire Congress Kingdom, which became completely absorbed into the Russian empire after the failure of the January Uprising. Norman Davies argues that changes including population growth, urbanization, and industrialization in parts of the Russian partition were stimulated by the decree issued by the Tsar in 1864 granting emancipation to Polish peasants. Now free of serfdom and for the first time owners of the land they worked on, peasants became more prosperous, increased in number, and started migrating to urban centers, mainly to Warsaw, or abroad in search of employment, thus fueling the growth of the urban working class. In addition, because of the elimination of tariffs, “the products of Polish industry could penetrate the vast Russian market.”14 Warsaw grew in population and became a fairly important center of industry, and even though it could not compete with the economies of the Polish western cities under Prussian rule, Davies contends that the progress achieved by Polish urban economies far surpassed the development of Ukraine and central Russia.15 This modest progress notwithstanding, the Polish population remained generally resentful of the foreign rule.

Like many fiction writers of her time, Eliza Orzeszkowa saw herself as both a student of the society and its mentor. It is not surprising, then, that in Marta she brings her protagonist into contact with several distinct strata of Polish society while at the same time Marta’s own social standing undergoes an important evolution. Like Orzeszkowa, she is born into the landed gentry. But both of them, Marta through her marriage and Orzeszkowa through her divorce, migrate to the Polish intelligentsia, an educated class for the most part descended from the gentry. However, while Orzeszkowa’s literary talent and the commercial success of her novels kept her well positioned within the intelligentsia, Marta eventually descends into the working class only to end up among the destitute. In her search for employment and in her daily struggles to survive, Marta’s encounters might point to the author’s sympathies and preferences. While the young woman meets many kind and generous representatives of her own class, the intelligentsia, and receives some support from a few sympathetic working-class characters, Orzeszkowa focuses her social critique on the bourgeoisie, represented in the novel by the rapacious, and even cruel, owners of the garment shops and workrooms. Marta never interacts with any representatives of the Russian occupying forces, and readers might be hard pressed to realize that Warsaw at the time was not a free capital of a free country. It is possible that this was a deliberate decision on Orzeszkowa’s part not only because of her single-minded focus on women’s issues but also in an attempt to ensure the novel’s open and legal circulation without any interference from Russian censors.

In general, Orzeszkowa pays very little attention to the uniqueness of her novel’s setting. The city exists as a vague background to her protagonist’s lonely struggle for survival. The reader’s perception of urban spaces becomes limited to Marta’s unhappy experiences. When the city is not mediated by her husband, it takes on a menacing quality. Its ever-present disquieting din intensifies Marta’s yearning for the past by bringing back her memories of the idyllic childhood on her father’s country estate and the blissful and carefree years of her marriage. At present, the streets of Warsaw seem to Marta at best indifferent, if not openly hostile. They are populated by servants, landlords, shop owners, sweatshop operators, shop assistants, artisans, men-about-town, intellectuals, and even high-class prostitutes who both individually and collectively fail Marta. To authenticate her novel’s setting, Orzeszkowa names a few well-known Warsaw streets and some churches, but she takes care not to turn Marta’s story into an exotic and uniquely Warsovian or even Polish plot. In this novel of purpose, Orzeszkowa’s primary focus is to illuminate women’s economic and sexual vulnerability and the failure of society to allow women equal participation in the economy.

Eliza Orzeszkowa introduces her protagonist at Marta’s most vulnerable moment, soon after her husband’s funeral, when she must move out of her comfortable upper-middle-class home to a substandard lodging in a poor neighborhood, and when she comes to a realization of her complete financial ruin. She is destitute. This young woman who must support both herself and her small daughter has absolutely no assets left after her husband’s illness and death, she has no living relatives or friends who could offer help, and her father’s estate has been lost to bankruptcy. Orzeszkowa uses this initial situation to highlight several social issues that stem from women’s disempowerment. As a woman of her class, Marta has not been educated but rather has been groomed to fulfill the role of a wife and mother and thus perpetuate the patriarchal power structure. Her search for employment reveals her total lack of any marketable skills and qualifications. Even though she is a natural artist and an intuitive writer, her skills were never developed through rigorous education. She can speak French, but not very well; she can draw, but not very well; and she can write, but not very well. She is not able to compete in a tight job market because she has not been prepared for an eventuality of not achieving her success through, as Perkins Gilman put it, “a small gold ring.” Even though she meets many kind individuals who are willing to provide charity, nobody can offer practical solutions to her situation because the problem is not unique to Marta but systemic.

Marta’s job search teaches her also about gender and class discrimination, social norms that women cannot transgress with impunity, prejudice against working mothers, the lack of good-quality child care, abominable working conditions and worker exploitation in sweatshops, cruelty in relationships with other women, and the double standard. She learns about the victimization of women by sexual predators who prey on the weak and vulnerable and shirk their responsibility for destroyed lives. She is shocked to realize that a young man will be admired for having numerous affairs or even keeping an expensive mistress, but a young woman’s reputation will be irreparably damaged by nothing more than being seen engaged in a conversation with a man in a public space.

Through Marta’s story and a detailed analysis of her changing emotional states and responses, Eliza Orzeszkowa traces a young woman’s journey of self-discovery from her carefree childlike persona controlled by her father and later her husband to independent, responsible adulthood. It is also a process that allows Marta to move beyond self and develop social consciousness. At first, she understands failure exclusively in personal terms—if only she had gained the skills required, she could have kept the job. But facing repeated disappointments leads her to recognize the restrictive power of social norms placed on women, especially on women of her class. Through this heart-wrenching process, Marta, originally so clearly identified with the upper classes of Polish society, begins to appreciate and understand the suffering of the economically dispossessed. She rages against the society that prevents her and many other women from fulfilling their sacred responsibility to themselves as well as to their children, from realizing their dreams of a fulfilled life and motherhood, and even from sustaining physical survival. How much more powerful this realization is than the awakening Edna Pontellier experiences in Kate Chopin’s feminist novel The Awakening (1899).16 After all, Edna’s journey of self-discovery, no matter how emotionally draining, is not hindered by the real existential issues that Marta faces. Edna, who is financially secure, whose children are cared for by a doting grandmother, and whose friends offer her emotional support, has the luxury to focus exclusively on her own psychological growth. Marta, a single and isolated mother, must find a job and earn a living to save her seriously ill child, for whom she cannot provide nutritious food, medicine, or even a warm bed. Orzeszkowa’s message is driven home over and over again: Marta succeeds in gaining psychological and social maturity, but society destroys her. The tragic resolution of the novel suggests that Orzeszkowa cannot identify a safe social space for this changed Marta. She appears to pose too much of a threat to the patriarchal status quo.

During her lifetime, Eliza Orzeszkowa was a popular writer and a contender for the Nobel Prize in literature, and her literary legacy earned her a prominent place in the history of Polish literature. Together with such writers as Aleksander Świętochowski, Maria Konopnicka, and Bolesław Prus, she represents the Polish Positivist movement. Tracing their ideological roots back to the philosophy of Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer, Positivists asserted that by the mid-nineteenth century, the world entered a period of systematic and continuous growth evidenced by numerous scientific discoveries grounded in experiment and reason. They perceived societies as living organisms to be described and analyzed using the language of natural sciences. In Poland, such theories fell on fertile ground after yet another failure of armed struggle, the January Uprising, to regain independence. The Polish intellectual elite, the intelligentsia, found Positivist ideas very attractive as they justified the rejection of military actions in favor of refocusing attention on rebuilding Polish society and ensuring that cultural connections persisted in the nation split among three separate foreign empires. Positivists set their goal on organic work that involved using only legal means to achieve the cultural and economic growth of Polish society.

Positivist ideals permeate Orzeszkowa’s literary output. In addition to women’s issues, Eliza Orzeszkowa focused on social improvement, education, and promoting self-fulfillment through hard work. Her interest in problems of her times led her to study the Jewish minority and resulted in two novels, Eli Makower (1875) and Meir Ezofowicz (1878). Meir Ezofowicz is especially interesting. Its title character, a young and sensitive Jew, rebels against his narrow-minded community. Undoubtedly, her greatest literary achievement was the publication in 1888 of her masterpiece Nad Niemnem (On the Banks of the Niemen), a beautifully written family novel that outlined Orzeszkowa’s Positivist social plans. The novel’s heroine, a young but impoverished genteel woman, has the courage to break social barriers by marrying an uneducated yet naturally intelligent and patriotic farmer. Through this marriage, she will bring education and progress to the whole village community, thus building a strong Polish society, which will be ready for independence when the time comes. Published almost twenty-five years after the disastrous end of the January Uprising in 1864, this novel suggests ways of coming to terms with a national tragedy of such magnitude.

In her personal life, Eliza Orzeszkowa continued to search for love and happiness, with mixed results. After being rebuffed by a much younger man for whom she formed a decidedly one-sided attachment, she finally found fulfillment in a relationship with Stanisław Nahorski, a well-known lawyer. Yet even this relationship was not without heartache. Nahorski was already married when he met Orzeszkowa, and he was unwilling to divorce his seriously ill wife. Orzeszkowa and Nahorski married only after his wife’s death. He was sixty-eight and she was fifty-three. Orzeszkowa continued writing and lecturing on social issues until her death in 1910. She devoted her entire life to the work for public good.17

Taking up a novel of social reform written almost 150 years ago, in a far-away country and in very different sociopolitical circumstances, we might be tempted to dismiss it as a quaint historical document replete with nineteenth-century melodrama. Yet the typical melodramatic tropes—the unambiguously drawn conflict between good and evil set on the stage of a “modern metropolis”;18 the effusive expressions of feelings; and the presence of stock characters who may not have deep “psychological complexity,”19 such as wealthy villains and beleaguered heroines whose virtue is constantly tested—should not to be discounted altogether. As argued eloquently by Kelleter and Mayer, “the melodramatic mode has always lent itself to stories of power struggles and to enactments of socio-cultural processes of marginalization and stratification.”20 Thus, it is hardly surprising that in Marta, Eliza Orzeszkowa successfully links the realistic with the melodramatic21 and employs this strategy to critique patriarchal power relations that marginalize women. She does not allow us to easily file away her ideas and concerns. While reading Marta, we are repeatedly struck by the author’s approach to women’s issues, which is decidedly contemporary—so much so, that we still struggle with many issues she outlined so long ago: the inequality in earnings between men and women, the lack of affordable child care, the educational difficulties that girls face in many countries, and the existence of the glass ceiling women still have not managed to shatter. Eliza Orzeszkowa’s Marta still has a message for us and still calls us to action.

Notes

1. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Women and Economics: A Study of the Economic Relation between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution (Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1898), 71.

2. Eliza Orzeszkowa, Marta, transl. Anna Gąsienica Byrcyn and Stephanie Kraft, intro. by Grażyna J. Kozaczka (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2018), 000.

3. Edmund Jankowski, Eliza Orzeszkowa (Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1964), 150–51.

4. Now in Belarus.

5. Eliza Orzeszkowa, O sobie (Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1974), 43–44. All translations from Polish-language publications are provided by the author of this introduction.

6. Poland regained independence in 1918.

7. The date of the dissolution of the Congress Kingdom of Poland has been disputed.

8. The tragedy of the January Uprising was captured by the Polish painter Artur Grottger (1837–1867) in a series of nine black-and-white drawings titled “Polonia.” These illustrations are housed in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, Hungary, and can be easily viewed online (http://www.pinakoteka.zascianek.pl/Grottger/Grottger_Pol.htm).

9. Orzeszkowa, O sobie, 102.

10. Ibid., 107.

11. Ibid., 110.

12. Jankowski, 154.

13. Ignacy Aleksander Gierymski (1850–1901), also known as Aleksander Gierymski, a Polish artist of the late nineteenth century, painted contemporary urban views of Warsaw.

14. Norman Davies, Heart of Europe: A Short History of Poland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 170.

15. Ibid., 171.

16. Both Kate Chopin’s novel The Awakening and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper” can be useful companion texts to Marta, as all three illuminate powerful social forces restricting a woman’s ability to construct an autonomous and fulfilled self. Each uses different narrative techniques to achieve a similar goal and to reach a strikingly similar conclusion. Perkins Gilman in her book Women in Economics suggests some solutions to the problem of women’s economic disempowerment that could also provide interesting material for a comparison with Orzeszkowa’s proposed solutions.

17. Further information about Orzeszkowa’s life and work can be found in Józef Bachórz, introduction to Eliza Orzeszkowa, Nad Niemnem (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1996); Grażyna Borkowska, Pozytywisci i inni (Warsaw: PWN, 1996); Grażyna Borkowska, Alienated Women: A Study on Polish Women’s Fiction, 1845–1918, transl. Ursula Phillips (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2001); Jan Detko, Orzeszkowa wobec tradycji narodowowyzwoleńczych (Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1965).

18. Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 13.

19. Ibid., 16.

20. Frank Kelleter and Ruth Mayer, “The Melodramatic Mode Revisited: An Introduction,” in Melodrama! The Mode of Excess from Early America to Hollywood, ed. Frank Kelleter, Barbara Krah, and Ruth Mayer (Heidelberg: Universitatsverlag Winter, 2007), 9.

21. More information about the connections between realism and melodrama can be found in Neil Hultgren, Melodramatic Imperial Writing: From the Sepoy Rebellion to Cecil Rhodes (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2014).

Questions for Further Discussion and Writing

1. What social, political, and familial forces shape Marta’s character and life? Are they responsible for her tragic end?

2. How do some of the novel’s episodic female characters manage to subvert male power and achieve substantial financial success? What do they sacrifice in pursuit of their success?

3. Orzeszkowa’s Marta illustrates the oppressive power of patriarchy that is detrimental to a healthy development of all members of society. How does the author present the system of power relations between men and women and the disempowerment of women? What attitudes toward patriarchal oppression do her female characters represent?

4. Marta has a very keen moral sense, and the necessity to transgress her moral code causes her great anguish. What is the source of Marta’s moral code, given that Orzeszkowa does not characterize her as a religious person?

5. Is Marta’s tragic fate at the end of the novel a predictable and logical outcome of her story? What is the root cause of Marta’s tragedy, and could it have been averted?

6. In her search for employment, Marta meets several kind men and women who attempt to help her, yet each time their efforts are in vain. Why? What prevents them from solving Marta’s problem?

7. Marta’s childhood friend Karolina uses men to secure a comfortable lifestyle for herself. What is Marta’s view of such an arrangement, and does she pass a moral judgment on Karolina? What does the novel suggest about the sexual vulnerability of women?

8. What are Orzeszkowa’s views on motherhood?

9. Orzeszkowa’s passion for her topic influenced her narrative technique. She repeatedly interrupts the flow of her narrative by including authorial commentary and analysis. Does this technique still appeal to contemporary readers?

10. How does Orzeszkowa connect gender and class as two powerful forces oppressing Polish women in the late nineteenth century? Was this a specifically Polish intersection of oppression or a broader problem highlighted in other literatures?

11. What does Orzeszkowa’s Marta contribute to the feminist conversation of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

12. Some literary critics analyze the tragic outcomes of such feminist texts as Kate Chopin’s The Awakening and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wall-Paper” in terms of the character’s personal triumph. Could the ending of Orzeszkowa’s Marta be described as Marta’s victory? Why or why not?