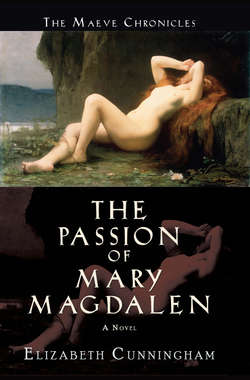

Читать книгу The Passion of Mary Magdalen - Elizabeth Cunningham - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE LOST THREAD

ОглавлениеI did not speak to my friends about what had happened to me with Anecius’s son—for so he was—my sense that some deity had taken me over for her own purposes. I say her purposes, because I had definite suspicions about Isis. I was wary of this roaming Egyptian goddess and even more alarmed by the priestess’s insistence that I belonged to her. Being a descendant of the goddess Bride—so my mothers claimed—I had taken goddesses for granted, and never felt the need to become a devotee any more than you might worship your grandmother, however much you loved her. I didn’t like the idea that a goddess could control my life. Deities ought to stay in their place, I told myself, in their own groves and wells and be thankful for the votive offerings that came their way. Though my ears pricked up whenever someone swore by Isis or prayed to her, I made no attempt to seek her temple again.

Bone had apparently decided not to report to Domitia Tertia my bolting from the litter and running off to a disreputable temple. As the whore chosen to initiate Anecius’s scion, I was in especially good odor. I had passed muster; my probation was over. I was allowed to go to onsite jobs—private orgies, power baths, literary soirees. Bonia also set up an in-house schedule for me, so that my regulars could count on finding me at home, so to speak.

In short, I was a success, more of a success as a whore than I had ever been as a student. On the surface of my life everything glittered. Winds of excitement and bustle whipped my waters into saucy little whitecaps. If I were a lake or a sea, you would want to sail on me. I’d give you a good ride but (mostly) not capsize you. No one could see past the sparkle to the depths where strange life forms lurked and currents no one suspected crossed and pulled, where the full force of me waited to be raised by some storm.

No one, that is, but Isis, who had staked her claim, whether I acknowledged it or not, who had begun training me as her priestess even before I knew her story and how it would restore the lost thread of mine.

The man appeared to be what we call an easy one—not arrogant, not awkward, not old, not young, not demanding anything in particular—or so I thought. I lay on my back for this simple sunny side up sort and reached for his cock to ease him in. He was ready. Ten strokes, I bet myself as I sometimes did to add interest. Then suddenly he leapt off me. He must have had strong upper arms for it seemed as though in one motion he was in the opposite corner of the room (granted it was small) pressed against the wall, staring at me with terrified eyes.

Slowly I rolled to my side and raised myself on my arm. No sudden moves. I had seen eyes like these before that looked at me but saw something else. It was one of the few things that frightened me. I looked to see if my bell was within easy reach, the bell that would bring Bone running. It was by the lamp. I began to inch my hand towards it.

Wait. There’s something here, a voice within me spoke. Yes, that voice again.

I didn’t want to hear it, but after a moment I answered: Then tell me what to do.

He needs a priestess, the voice said.

He came to the wrong place then, I shot back.

Did he?

I looked at the man and noticed details I had missed before. He was beginning to grey; his face had some deep lines, but in this moment he looked young, terribly young.

“I won’t hurt you,” was all I could think of to say.

He shook his head; then he covered his eyes. When he uncovered them, I saw that he was back from wherever he had gone. He knew where he was—in a tiny room with a whore who meant nothing to him. But his face was so bleak, instead of feeling relieved I felt my own sorrow stirring.

“Forgive me,” he said and turned to go.

“Is that what you need?” I asked.

The man stopped in the doorway; very slowly he turned around, and looked at me, really looked at me, as he had not before.

“What did you just say?”

“Do you need someone to forgive you?”

He didn’t answer right away, but he remained in the doorway.

“I cannot be forgiven.”

I sighed. If I had had a watch I might have looked at it. What did I care what this man had done? He’d had his time with me; let him pay and go.

He is a stranger, the voice inside said.

He’s strange, all right.

The god-bearing stranger, but the god in him is wounded.

Not this god shit again.

Yes. Will you help him?

I have a choice?

The voice inside was silent. There would be no force here. I looked at the man, the stranger, and suddenly I remembered how everyone at druid school had called my beloved the Stranger; they feared him, too; they thought he was a god; they tried to make him one—on their own terms.

“Tell me,” I heard myself speaking to the man. “Come and tell me.”

“Are you a priestess?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, surprised by my certainty. “Come closer to me.”

For I suddenly knew I needed to hear whatever he would tell me not only with my ears but also with my hands. Without instruction from me, he knelt before my low bed. As he spoke, I put my hands on his heart. He poured out what seemed at first an ordinary tale of youthful indiscretion—a love affair with a young married woman, no more than a girl, really, whose marriage had been arranged by her father. A typical story. They were caught, of course, and brought to trial. Guilt meant a fine for him, divorce for her, and separate exiles for both. Or so he thought, persuading himself that once outside of Rome they could meet again and begin a new life.

“The night before I left, I bribed my way into her husband’s house in secret. She begged me not to leave. ‘He’s sending me back in the morning,’ she kept sobbing, ‘back to my father’s house.’ But I didn’t understand what she was saying. I went over our plans of how and where we were to meet. She clung to me and wouldn’t be comforted. I was afraid we’d be caught again, so I tore myself away and headed for the port to board my ship in time for the next tide. While I was sailing free into the rising sun.…” He paused and seemed not able to breathe for a moment. I waited, silent, my hands burning on his heart. “…her father strangled her.”

My throat closed, too. All my muscles tensed. I wanted to fling him away. He had left his beloved to be killed by her father. Killed by her father. I would not forgive him; I refused. He was right; he could not be forgiven—even if it was not his fault.

As I looked at the man kneeling before me, trying to control my rage, I saw Esus galloping across the Menai Straits, not looking back, leaving me alone to face the druids, to face my father who reviled me as his daughter and wanted me dead. My father would have killed Esus, too. Made him a holy sacrifice. I had forced Esus to go; I had commanded him to go. It was not Esus’ fault, not his fault that he had left me.

I hadn’t known until this moment that I blamed him.

Suddenly it dawned on me: What if Esus blamed himself?

Esus could not know that my father had killed himself. He could not be certain that I had survived. Why had I never thought of that? This man trembling between my hands was unable to forgive himself. Could my own beloved be suffering this way?

I closed my eyes and had the dizzying sense of being able to see everyone’s story—this man sailing away while his beloved died; the girl staring into her father’s face as his hands closed on her throat. Esus seeing the hard, exposed Cambrian rock rise up before him as a huge, black tidal bore swept the straits cutting off his pursuers. And I saw myself, calling the storm, howling as my water broke and my childbirth began.

Then all the images dissolved as I saw everything through the eyes of the one who weeps rivers, the one whose lover drifts away in a coffin.

“Since then,” the man was saying. “I have not been with a woman. Whenever I have a woman in my arms, I see her face; I hear her begging me not to leave her.”

He fell silent and stayed motionless with his head bowed, waiting for my judgment. I became aware that I was breathing evenly again, a great steady tidal river of breath. The fire flowed through my hands into the man’s heart. But something more was wanting.

If you are willing, the inside voice said, I will open the way.

I am willing.

Again I saw through the eyes of the one who had known all sorrow.

“Beloved,” I answered in her voice. “I am the mistress of the living and the dead. Speak to your love, and she will hear. Comfort her and be comforted.”

I raised him from his knees, and held him in my arms while he called her by name and wept. When he entered me, she received him; I received him as the lover I had lost.

One morning not long after this encounter, I woke early feeling cold. Outside the wind stirred, wakeful like me. I could hear the dried, fallen leaves of the atrium’s vines and trees scudding along the stone.

It was almost Samhain by my reckoning, my people’s new year, the season of my birth, the time when boundaries between this world and the Other World shimmered and thinned. Soon the Pleiades would rise again in the night sky; wandering bards and bands of warriors would find a place to winter; the cattle would come down from the hills; the migrating flocks of birds would disappear. The thought of all this movement made my tiny, stale room unbearable. I took my mantle and coverlet and went down to the atrium where I sat in a corner and leaned my head back to see what I could of the sky. It was that dim indeterminate color that dawn watchers know goes on and on before the light quickens. I pulled my wraps around me and decided to wait for the sunrise. Olivia the cat found her way under my cloak and curled against my heart.

I must have gone into a light doze, halfway between sleeping and waking. I became aware of a low tuneless humming, a humming almost like human purring. Or maybe it was only Olivia. It went on and on, and a whispering rhythmic sound became part of it. The sound soothed me, like the sound of small waves on a pebble beach. Then I heard a song, or maybe I dreamed it.

I am the mother of the living

I am the lover of the dead

From the womb I knew my lover

Now I seek him in the riverbed.

The song rose and receded, rose and receded, the waters of a river, the river I had dreamed before, the dream of being tangled in the weeds. Now I drifted in a boat shaped like a crescent moon. In the shallows I would reach into the water and pull out a hand, a foot. I felt no horror at my finds. I was aware only of a diligent sorrow and the song going on and on until I knew the song was mine.

I am the mother of the living

I am the lover of the dead

From the womb I knew my lover

Now I seek him in the riverbed.

No! I wanted to speak. He is not dead. I saved him; I sent him away across the straits and raised the tide to protect him. But the song kept singing through me, and the boat kept drifting through the reeds, blown by a hot, malodorous wind.…

I opened my eyes to find an old woman’s face inches from my own. Her breath stank and whistled through the gaps in her teeth. She held a tiny glass vial, from which she pulled a stopper that proved to be a tiny blade. With it she delicately but firmly scraped my cheekbone, just below my eye. She held the blade poised for just a moment; it held a single, intact tear, which she carefully slid into the vial. Then, with the same precision, she harvested two more tears before she sealed the vial with the stopper.

I had been too astonished to speak, but now, as she drew back (and I could breathe again), I saw that old Nona the sweeper had accosted me. I had seen her only rarely; she swept while the whores slept, and went to bed around the time the house opened.

I managed a feeble, “What the fuck?”

“Whores’ tears.” She grinned, displaying all three teeth. “Cure anything. Couldn’t waste ‘em.”

“I’ve never heard that claim before,” I said with more resignation than indignation. My life had been riddled with crazy old crones. It was as much a relief as an irritation that one of them had caught up with me here.

“Old Nona’s the onliest one who knows,” she crooned, and then she cackled. “How do you think I live so long?”

She was speaking Latin but with an accent I couldn’t place—or it could have been the effect of her near toothlessness.

“Those are my tears.” I felt ornery.

“Not anymore.”

Nona slipped the vial, which she wore around her neck suspended on a string, inside her tunic where it rested between whatever was left of her breasts. Then she picked up her broom and began sweeping the fallen leaves into a crescent shape. She hummed while she worked, and I recognized the tunelessness. It was her voice that had threaded through my dreams.

“Who are you?” I demanded. I had met old women before who turned out to be goddesses or close relations. You couldn’t be too careful.

“Nona, Nona, Nona. No name Nona,” she replied unhelpfully. “That’s what everyone calls me. I don’t remember my other names.”

She started to sing.

I am the mother of the living

I am the lover of the dead

From the womb I knew my lover

Now I seek him in the riverbed.

“You sent me that dream,” I accused.

“What dream would that be, dearie?”

“The river, the boat, searching for my lover. You know!” I insisted.

My tears welled again, and I knuckled them back into the ducts before she could come and steal them with her tiny scalpel. She paused in her sweeping and eyed me intently, her eyes black, her head cocked like a bird’s. Then she laid her broom against the wall, crossed the atrium and prostrated herself before me. The next thing I knew, she was kissing my feet.

“Stop!” I protested. “Are you crazy?”

I hardly needed an answer, I thought. But she did stop, and when she got up again, she plucked my hand.

“Stand up, domina,” she urged. “Come.”

Domina? I was too confused and, I confess, curious to resist. Besides, this tiny old woman’s grip had the fierceness of a newborn’s, and the authority of a mother’s. Dislodging Olivia, I stood and followed where she led me. I was disappointed when we only went as far as the Lararium, a miniature temple, a sort of dollhouse for the gods. All Roman households had one on display, a locus for the care and feeding of the family’s personal gods. The Vine and Fig Tree’s Lararium, complete with miniature columns and a fresco depicting Mount Olympus, was tucked away in one of the smaller reception rooms. It was quite crowded both with such jolly well-known types as Venus and Bacchus as well as more obscure figures crudely fashioned by the whores and other house slaves to represent the gods they remembered from home. Bone’s many breasted—or, as he insisted, testicled—goddess was displayed prominently, and there was a Priapus, whose enormous prick was garlanded with single earrings that had lost their mates. Even the cats had a deity, a stately obsidian cat Dido had introduced as Bast.

I’d never had more than a nodding acquaintance with any of these figures and had not added to the population. My gods, untamed, shape-shifting gods, did not belong here. I would never insult them by giving them a fixed form and cramming them into a little box, as if they, too, could be confined and controlled, as if they, too, were slaves.

Nona dropped my hand and beckoning me to look more closely, she pointed to a figure in the back that I hadn’t noticed before. She stood a little taller than the rest or maybe it was just the horns she wore that cradled the star-like flower. She was robed in gold, just like the statue in the Temple of Venus Obsequens. In one hand she held a sistrum; in the other an ankh.

“Almighty Isis,” said Nona.

“We’ve met.”

Nona just nodded. Then she reached into her tunic, lifted the vial from around her neck and handed it to me. I looked at her uncertainly.

“Pour some for her.”

“But I thought you said you lived on whores’ tears,” I argued for the sake of argument.

“These tears are her tears,” said Nona. “Pour the tears over her.”

I shrugged. There was no harm in humoring her. Taking care not to knock anyone over, I reached into the Lararium and poured a few drops of the salty water on the figure’s head. It pooled in the petals of the flower, then overflowed and began to trickle down her terracotta face.

“Her tears,” Nona repeated.

I closed my eyes, and the dream came back, the boat curved like the moon, the river, the mud, the severed limbs, the sorrow.

“When the moon is full again, it will be the Isia,” Nona announced.

“The Isia?” I felt a prickling at the base of my skull. Whatever it was, this Isia happened at the same time as Samhain.

“The mysteries, the sorrows. We who belong to Isis mourn with her, search with her. The priestesses go in moon-shaped boats to seek the Beloved in the waters. When he is found, we rejoice. We embrace the stranger, and everyone eats.”

I suddenly understood—no, that’s wrong; I didn’t understand anything—but I knew: I had been dreaming Isis’s story. Why? Why was this goddess pursuing me?

“Little Bright One,” she called me by my mother’s name for me, and I could no longer see, but I felt her take the vial from my hand. How could a flood fit in that tiny container? “You belong to her.”

Before I could argue, Old Nona was gone.