Читать книгу Like Wings, Your Hands - Elizabeth Earley - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. May 13, 2015: 20,000 feet

ОглавлениеOn the plane to Bulgaria, Kali saw the high view of the past nineteen years of her life since she’d left there to come to America. The years contained so much—falling in love, having another abortion, having a baby, falling out of love, getting divorced, watching him leave their child, accepting her mother, Lydia, as the surrogate other parent to her son when she hadn’t even filled that role for Kalina as a child. Only Lydia called her Kalina anymore. In Bulgaria, before 1999, she had always been Kalina. In the States, after 1999, she was Kali.

When Kali left Sofia, she went to the South Shore of Boston to be a nanny for wealthy children there. Lydia followed her six months later. Kali’s host family let her mother stay there with Kali for a few months until Lydia herself found work as a nanny. Lydia’s wealthy children belonged to a family with a townhouse in Cambridge and a mansion in Lincoln, Massachusetts.

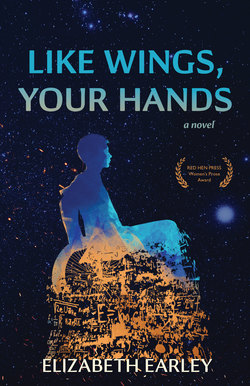

Kali recalled all of this while she catheterized Marko. She was embarrassed to have to do it right there in his seat, but there was no other option. His wheelchair was gate checked and she couldn’t carry him to the tiny airplane lavatory. She put a blanket over his lap for privacy, even though he seemed oblivious. He was busy with his screen time. He was watching reruns of Red Sox games. Kali knew he’d rather be watching porn, or “kissing videos” as he called them. He had a cache of videos of people kissing, both people and cartoon characters, actually—a vanilla collection that he allowed his mom to know about. But Kali was aware of the harder core stuff he had hidden behind a password-protected folder. She’d thought about making him get rid of it, but decided to let him be. There was the inevitability of it on the one hand, him being a teenage boy much like any teenage boy, but then, on the other, was the heartbreaking part. The part Kali couldn’t bear to think about. What kind of romantic life would he be able to have with no sensation in his pelvis—no sensation anywhere below his waist?

Kali knew that sex is 95 percent mental—that the pituitary gland is the hub that produces all the chemicals that make the body feel so on fire about it. And Marko’s pituitary gland was alive and functioning, so why couldn’t he have a full and active sexual life, even without the use of his penis? Even without a partner? Thus, the videos. Kali couldn’t deprive him that.

The woman in the seat next to her in their row was staring unabashedly at Kali prepping the catheter. She looked away when Kali inserted it into Marko’s penis, and then looked back when she re-covered his lap. Kali made eye contact with her and she looked away.

“He has spina bifida. Paralyzed from the belly button down,” Kali said. The woman gave her that look she knew so well. It was a look of admiration and pity that Kali couldn’t stand. It made her nervous to have it this close to her. She fought the urge to slap the woman, to knock the look right off her face.

“I’m sorry,” the woman said. Kali didn’t respond. She went about taking the cath back out, as the bag was nearly full. Marko was moving his hands rapidly and rhythmically, so Kali couldn’t get a steady hand on the tube. She grabbed his arms and pinned them down, which startled Marko. Immediately, she regretted having been so rough with him.

“I’m sorry, sweetie, can you hold still for just a moment until I’m done here?” she said, apologetic in tone. It worried Kali slightly that Marko held so still and was so quiet while she removed the tube and cleaned him up.

“You okay?” she asked. He nodded and she smiled. With the used catheter and bag gathered up, she needed to get up and dispose of everything and wash her hands. She gave a look to the woman next to her and started to rise, aware even as she did that it was a simple luxury—this bearing of weight on her legs—that her son would never experience. As the woman stood up and moved aside to let Kali out, that thought made her aware, more intensely than usual, of how completely this basic guilt was woven throughout her life and everything she’d done since Marko had been born fourteen years prior. This brought her thoughts, again, to Lydia and when she first came to the States.

Kali moved carefully down the plane’s aisle, absorbed in the memory. Lydia had come initially, or so she said, to merely visit Kalina. But after a month and a half lapsed and her mother was still there with no plans of leaving and dwindling money, Kali began helping her look for work. Kali understood that Lydia didn’t want to return to Bulgaria and be alone with her father, Todor, who was chronically depressed and who routinely threatened suicide, to the extent that it no longer had any shock value left. Kali herself had just stopped talking to him shortly after moving away, not wanting to bear the emotional burden of his pain.

The kind of work that could sponsor a visa and keep Lydia in the United States for longer than six months was abundantly available in New England, given all the rich, white people having kids. After Lydia found a family to nanny for, Kalina didn’t stay at her job long. She left and became a student, going to graduate school for psychology. That’s where she met Marko’s father, Zach, and started that whole journey. Looking back now, Kali could see the inevitability of it all—like a black line running across the clear sky, its unwavering trajectory carved solidly against a dramatic canvas of deep blue.

Kali, Zach and Marko spent whole days with Lydia at the mansion in Lincoln, swimming in the pool, lounging in lawn chairs in the family’s acres-big backyard. After the parents divorced, the man promptly remarried a much younger Russian woman who didn’t like Lydia. With the kids grown and off to college, Lydia soon found herself out of the mansion and back on her own in a country that still didn’t feel like home.

Marko was six at the time and Lydia came to live with them. Kali, having become integrated into the yoga community, connected Lydia with people she knew at the ashram—a spiritual yoga retreat in the suburbs. Lydia was able to get a small apartment there and a job cooking as well as another part-time job at the local Montessori school. This way, Kali was able to visit her at the Ashram and sometimes leave Marko there with her for a few days so she could get away. To Kali’s mind, it was the perfect solution; Lydia could also come to the city to visit Kali and Marko, but they didn’t have to be on top of each other. She loved her mother, but too much time together often led them down a path of buried resentments from older, deeper wounds.

And now Kali was headed back to Bulgaria for the first time in fifteen years. She opened the door to the little airplane lavatory, disposed of the catheter bag, and washed her hands. She thought of her son. Marko would see Sofia for the first time and meet his grandfather, Todor, who Kali thought might actually, finally, be dying for real. When Lydia had told Kali she was going back to stay with him because he was sick, she had known it must have been serious. Faced with the reality of his death after having been estranged from her father for nearly two decades, she decided, somewhat spontaneously, to return and see him one last time and let him meet his grandson.

When Kali walked up the aisle to return to her seat, she squeezed past the woman who had been sitting next to her headed in the opposite direction, looking uncomfortable. Marko must have over-shared something with her, Kali thought, then laughed to herself. She returned to her seat to find her son, face upturned and illuminated by the sunlight streaming in through the window, hands carving elegant arches and angles in the space before his face.