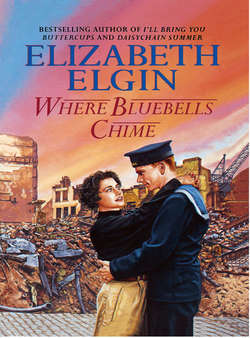

Читать книгу Where Bluebells Chime - Elizabeth Elgin - Страница 18

13

Оглавление‘There now, Gracie Fielding, you’ve just witnessed a little bit of tradition.’ Jack Catchpole pressed the flat of his boot against the soil around the little tree.

‘I have? Well, I know we’ve planted four rowan trees and the house is called Rowangarth – so tell me.’ Anything at all about the family who owned the lovely place she worked at fascinated her.

‘You’ll know the house was built more’n three hundred years ago, when folk believed in witches, and you’ll know that rowan trees keep witches away?’

‘I didn’t, though I suppose people believed anything once.’

‘Happen. But the Sutton that built Rowangarth must’ve believed in ’em, ’cause he planted rowan trees all round the estate at all points of the compass, so to speak. They’m bonny little trees; white flowers in summer and berries for the birds in winter, so it became the custom to plant the odd rowan from time to time, just to keep it going. My dad planted half a dozen before Sir John died – that cluster in the wild garden – and now it’s my turn to do a bit of planting, an’ all. Can’t have a house called Rowangarth, and no rowan trees about, now can us? And you never know about witches – best be sure.

‘Just a tip about when to plant trees, lass. Plant a tree around Michaelmas, the saying goes, and you can command it to thrive, but plant a tree at Candlemas and all you do for it won’t ever come to much. It’ll be a weakly thing alus.’

‘When is Candlemas, then?’

‘February, and the ground cold and unwelcoming. But those little rowans will do all right, ’cause it’ll be Michaelmas in a couple of days.’ He laid spade and fork in the wheelbarrow then shrugged on his jacket. ‘Now didn’t you say you had something for me at Keeper’s?’

‘I did, and you’re welcome to it. Remember you gave me a sack? Well, it’s half full of hen droppings now and starting to smell a bit. I don’t want Daisy’s mother to complain, so don’t you think we should move it?’

‘We’ll collect it now, while we have the barrow with us,’ he said eagerly. If it was starting to smell, then Tom Dwerryhouse might get wind of it, try to get hold of it for his own garden. ‘Then I’ll show you how to make the best liquid fertilizer known to man!

‘Have you heard about the party? All Rowangarth staff’ll be there, so that’ll include you. Supposed to be a bit of a do for the Reverend and Miss Julia’s wedding anniversary, but really it’s for her ladyship’s eightieth. They’re aiming for it to be a surprise for her. Reckon all the village’ll go and there’s to be dancing, an’ all. But not a word, mind, about it being for Lady Helen or if she gets to hear about it she might say she doesn’t want the fuss of it, and Miss Julia’s set her heart on a party.’

It was a sad fact that the mistress was growing old, though considering the tribulations she’d had she had aged gracefully, Catchpole was bound to admit. And when her time came she would be sadly missed, because real ladies were few and far between these days.

‘I thought she looked tired, t’other day, when she came to look at the plants.’

‘Tired, Mr C.? If I look as good as she does when I’m her age, I won’t complain.’

That day, Gracie recalled, Lady Helen had asked for her seat to be put in the orchid house. They kept a special green-painted folding chair in the small potting shed and Gracie had brought it for her and stayed to talk about the orchids and especially about the white one which seemed to be about to flower, when really it shouldn’t be flowering.

‘My dear John gave the original white plant to me – oh, more years ago than I care to remember, Gracie,’ Lady Helen had said, her eyes all at once gentle with remembering. ‘There are eight plants now, all taken from that first one. No one was to wear the white orchids but me, he said. They were to be mine alone, though Julia carried them at her wedding – her first wedding, that was.’ She had touched that fat orchid bud as if it were the most precious thing she owned.

‘Lady Helen seems very sentimental about the white orchids,’ Gracie said now.

‘Aye. Remind her of Sir John, young Drew’s grandfather. Killed hisself speeding on the Brighton road in his new-fangled motor. Afore the Great War, that was, when I was a lad serving my time at Pendenys. Took it terrible bad. Wore black for three years for him. They don’t wear black these days like they once did. For those three years her ladyship didn’t receive callers nor socialize ’cause her was in mourning. Folk don’t have the respect nowadays that they used to have.’

He sucked hard on his pipe, remembering the way it had been in Sir John’s time.

‘What are you thinking about, Mr Catchpole?’

‘Oh, only about the way it used to be.’

‘I wish you’d think out loud.’

‘I will. Tomorrow, happen. What I’m more concerned about now is that sack you’ve got for me at the bottom of Alice’s garden. Away over the stile and get it, there’s a good lass. And go careful. Don’t want to set the dogs barking.’

He smiled just to think of it. That hen muck was worth its weight in gold. Wouldn’t do if it fell into the wrong hands!

Edward Sutton lounged in a comfortable basket chair in the conservatory at Denniston House, gazing out over the garden to the fields beyond and the trees, yellowing now to autumnal colours. Strange, he thought, that not since he married Clemmy so many years ago, and gone to live in Clemmy’s house, had he been so contented.

It had always, come to think of it, been Clemmy’s house, built for his only child by an indulgent father; always been Clemmy’s money he lived on and their firstborn, Elliot, had been Clemmy’s alone.

Now Clemmy was dead, and Elliot, too, and now Edward himself lived at Denniston House with Elliot’s widow, Anna, and Tatiana, whom Clemmy had never forgiven for being a girl. Anna was charming and kind and Tatiana a delight of a child and he felt nothing but gratitude to the Army for commandeering Pendenys Place. They were welcome to it for as long as the fancy took them. He glanced up sharply as the door opened.

‘Uncle Edward! Did I wake you up?’

‘No, Julia. I wasn’t asleep. I was just indulging an old man’s privilege of remembering and do you know, my dear, when you get to my age you can dip into the past without any qualms of conscience or regret?’

Dear Julia. She still called him uncle, though for these two years past she had been his daughter-in-law. He offered his cheek for her kiss, smiling affectionately into her eyes.

‘I know. I do it always when I come here to Denniston. And it doesn’t trouble my conscience either, because now I am the parson’s wife and middle-aged, and the girl who was once a nurse here is long gone.’

‘Of course! You and Mrs Dwerryhouse did your training at Denniston in the last war.’

‘And now Drew is in the thick of another one, and Daisy soon to join him.’

‘Drew is a fine young man, Julia. How is he?’

‘The last time we heard he was in port – tied up alongside, he called it – having something done to his ship. He didn’t say what, though. All I know is that the Penrose is part of a flotilla that keeps the Western Approaches free from mines. But we’ll find out more when he gets leave. You know,’ Julia reached out to touch the wooden table at her side, ‘I have a good feeling about Drew. I know, somehow, that he’ll make it home safely one day. But I’ve come with an invitation. I’ll tell you both about it when Anna has finished phoning.’

‘I already know about the secret party,’ Edward chuckled. ‘Tatiana brings me all the gossip and news. But Anna is always on the phone, lately, trying to get through to London. There is such a delay on calls – if you can get through at all, that is. Poor Miss Hallam on the exchange must be having a very trying time. And the delays have got worse. They say it’s because of the bombing.’

Unable to break Fighter Command, Hitler had turned his hatred on London, swearing it would be bombed until it lay a smoking ruin. Night after night the Luftwaffe came. Poor, poor London.

‘It must be. I booked a call to Montpelier Mews yesterday evening and I got it half an hour ago. It seems that Sparrow is coping with it all. When the sirens go she says she puts her box of important things in the gas oven, then takes her pillow and blankets and sleeps under the kitchen table.’

Mrs Emily Smith: Andrew’s cockney sparrow. Once, in another life when Andrew lived in lodgings in Little Britain, Sparrow was his lady who did. Now she took care of the little mews house that once belonged to Aunt Anne Lavinia.

‘Sparrow! I sometimes forget that Anne Lavinia left you her house, Julia. Is it all right? No bomb damage?’

‘Not so far. I’ve told Sparrow she must lock it up and come to Rowangarth, but she won’t hear of it. Hitler isn’t going to drive her out of London, she says, and insists she’s safer than most. It’s the people in the East End who are taking the brunt of it, though the papers say that Buckingham Palace has been bombed. Everything’s all right at Cheyne Walk, I suppose?’

‘I suppose it is. Do you know, Julia, I’d forget all about that house if it wasn’t for the fact that Anna’s mother and brother live next door. It’s been nothing but a nuisance. I could never understand why Clemmy insisted on buying it. I suppose some good did come out of it, though. Elliot and Anna met there.’

‘Yes.’ Julia had no wish to talk about Elliot nor even think about him and was glad when Anna came into the room. ‘Did you manage to get through?’

‘No, I didn’t.’ Anna and Julia touched cheeks in greeting. ‘It seems Mama’s number is unobtainable. What can it mean? Has Cheyne Walk been bombed, do you think? What am I to do?’ Anna was clearly distressed. ‘I asked Mama time and time again. “Come to me,” I said. I warned her that London would be bombed but no – the Bolsheviks drove her from her home in Russia and Hitler wasn’t going to drive her from this one, she said, poor though it was.’

‘Poor? But the Cheyne Walk house is rather a nice one,’ Julia protested.

‘I know, I know!’ Anna paced the floor in her agitation. ‘But you know my mother, Julia. Always the Countess, always in black, mourning for her old way of life. She can be very stubborn. Do you think I should go down there?’

‘No, I do not! All around the docks and a lot of central London seems to be in a mess. I doubt you’d be able to get on a bus, let alone find a taxi. It would be madness to go there at a time like this. Your mother has Igor to look after her and –’

‘Not any longer! Igor is an air-raid warden now. Since the bombing started, he’s hardly ever at home!’

‘Anna, my dear.’ Edward Sutton rose slowly to his feet to lay a comforting arm around his daughter-in-law’s shoulders. ‘No news is good news, don’t they say? The Countess will be in touch with you before so very much longer. Perhaps it’s only a temporary thing. Leave it until morning and it’s my guess you’ll get through with no delay at all. Try not to worry. And Julia is here with an invitation for us.’

‘Aunt Helen’s party, you mean? We’ve already heard about it from Tatiana. Daisy told her.’

‘Well, I’m here with the official invitation for the fifth. And don’t forget, Anna, that it’s our party – Nathan’s and mine. And tell Tatty there’ll be dancing, so she’ll be sure to come.’

‘I’ll tell her.’ Tatiana was so secretive these days. Always slipping out or hovering round the telephone. Anna frowned. A young man, of course, but why didn’t she bring him home? ‘She’s in Harrogate this afternoon, collecting for the Red Cross. She said she would come home on the same bus as Daisy.’

‘So it’s settled. We’ll all come. And here’s tea,’ Edward smiled as Karl, straight-backed and unsmiling, laid a silver tray on the table beside Anna.

‘Where is the little one?’ he demanded in his native tongue.

‘Out, helping the Red Cross. She’ll be all right …’ Anna smiled apologetically as the door closed behind the tall, black-bearded Cossack. ‘I’m sorry. He refuses to speak English. I’ve told him it isn’t polite when we have guests, but he’s so stubborn. And he does understand the language. I’ve heard him talking to Tatiana in English. I think it amuses him that people get the impression he doesn’t know what they’re saying.’

‘He’s a good servant, though,’ Edward defended. ‘So loyal, still, to the Czar and surely it’s a comfort to you, Anna, that he’s so protective of Tatiana. How old is he?’

‘I don’t know. He won’t ever say.’ Anna placed a cup and saucer at her father-in-law’s side. ‘But it’s my guess he’s about fifty-five. He’d been a Cossack for some time when he met up with us. We couldn’t have got out of Russia without his help. He’s been with us ever since.’

‘He and Natasha, both. Didn’t you pick up Natasha along the way, too?’ Julia wanted to know.

‘Sort of. She was the daughter of the woman who did our sewing,’ Anna replied in clipped tones. ‘When the unrest first started, she was delivering dresses to us at the farm at Peterhof – we’d gone there for safety. Mother insisted that Igor take her back to St Petersburg, but when they got there the rabble had taken over their house and her parents gone. What else could Igor do but bring her back to us?’

‘Whatever became of her?’ Julia persisted. ‘She went back to London with you, didn’t she, after – after –’

‘After my son was born dead, you mean? Yes, but she didn’t stay long at Cheyne Walk. She left Mama and went to France; Paris, I think it was. I can’t remember. It was a long time ago. But do have a biscuit, Julia …’

‘Positively not!’ Biscuits were rationed and she and her mother would not eat other people’s food. ‘And those are homemade, too,’ she sighed.

‘Cook has a little sugar stored away.’ Anna blushed guiltily because no one should have sugar stored away. ‘But I think it will soon be used up,’ she hastened.

‘Mm. So has our cook. I think people who remember the last war quietly bought in a few things – just in case. I know Tilda has a secret stock of glacé cherries.’ Julia had been quick to notice the tightening of Anna’s mouth, the dropping of her eyes. Did she still mourn her stillborn baby or was it thoughts of the man who fathered it that brought the tension to her face because no one, not even the compliant Anna, could have been happy with Elliot Sutton.

‘I think Tatiana is meeting Daisy in her lunch hour.’ Deliberately Julia talked of other things. ‘They’ll spend most of it searching for cigarettes, I shouldn’t wonder, though Tatiana told me the other day she was down to her last smear of lipstick, so perhaps they’ll be looking for a lipstick queue.’

‘I’ll give her one of mine,’ Anna smiled, all tension gone. ‘Now won’t you have just one biscuit?’

‘Absolutely not, thanks. And did you see it in the papers this morning? When the new petrol coupons start in October, petrol is going up to two shillings a gallon!’

‘Two shillings and a ha’penny, to be exact,’ Edward smiled, ‘and cheap at twice the price when you think of the lives it costs just getting it here.’

‘Cheap,’ Julia echoed, all at once thankful that exploding mines in the Western Approaches seemed safer by far than bringing crude oil to England. Seamen crewing a tanker deserved all the danger money they were paid when just one hit was enough to send the ship sky-high. There were no second chances on a tanker. Either men died mercifully quickly or perished horribly in a sea of blazing oil. ‘And only the other day I was thinking about people who get petrol on the black market and wondering if I could come by the odd gallon. Very wrong of me, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes, but very human,’ Edward said softly. ‘You won’t be tempted, will you, Julia?’

‘Oh, I’ll be tempted all right, Uncle, but I won’t do it – promise. And I’ll have to be going. Nathan is visiting the outlying parishes this afternoon and Mother is inclined to brood, if she’s alone for too long – about Drew, you know.’ She rose to her feet. ‘Now mark it in your diaries: October the fifth. It’s a Saturday. No big eats, I’m afraid, but it’ll be a lot of fun. Sorry I can’t stay longer.’

‘That’s all right. Give Aunt Helen my love,’ Anna smiled as she closed the conservatory door behind them. ‘And I think I’ll ask the exchange to try Cheyne Walk just once more. She’ll think I’m fussing, but I’m so worried, Julia. You honestly don’t think anything awful has happened, do you?’

‘No, I don’t. Somewhere along the line, a telephone exchange has been bombed. Even a telegraph pole getting knocked down could cause a lot of upset with the phones. You’d have heard something, by now if – well, if there was anything to tell.’ She reached for Anna, hugging her close. ‘Try not to worry too much if you don’t get through, but either way, give me a quick ring, will you? ‘Bye, Anna.’

‘Grandfather will be so pleased with the tobacco,’ Tatiana said. ‘I know he’s short. Last night he kept looking in his tobacco jar, then putting the lid back.’

‘Dada’s always short, poor pet. D’you know, Tatty, I nearly hit the roof when we got so near to the counter and then the man said, “Sorry. That’s all, I’m afraid.” And then he said, “Cigarettes all gone, for today. Only pipe tobacco left. Half an ounce to each customer.” Imagine standing there for nearly half an hour for four slices of tobacco. I shall give two to Dada and two to Uncle Reuben. It’s all Hitler’s fault. I hate him.’

‘Doesn’t everybody?’ The bus stopped at the crossroads and they got out, calling a good night to the remaining passengers. ‘Shall I walk part of the way with you – stand at the fence till you’re through the wood, Daisy?’

‘No thanks. I’ll be fine. It isn’t dark yet. And I know Brattocks like the back of my hand – even in the blackout. I don’t suppose you’ll be going to the aerodrome dance tomorrow?’

‘Not a lot of use. Tim’s almost certainly on ops. tonight and as soon as he gets back he’ll be off on leave to Greenock. I’ll miss him, but at least I’ll know that for seven days he’ll be safe. I’m getting up early tomorrow. He’s promised to ring the coin box in the village. Better than him ringing Denniston.’

‘You’ll have to set your alarm, and get out of the house without anyone hearing you. Wouldn’t it have been better to get up early and wait by your own phone and pick it up the second it starts ringing? It’s awful for you having to be so sneaky about Tim’s calls.’

‘I know, but I can’t risk them finding out at home. Mother might say I wasn’t to see Tim again and they’d watch everything I did, after that. Karl especially.’

‘Listen, Tatty, I know I might be out of order, but Karl only watches over you because he’s so fond of you. Haven’t you ever thought of confiding in him – telling him about Tim? He might even be on your side, cover for you sometimes.’

‘He won’t. First and foremost he’s loyal to Mother. She’s still his little countess,’ she sighed. ‘I really couldn’t risk it. I know I can get out of the house in the morning and it’ll be worth the walk because there’ll be no risk at all of anyone hearing what I say. I’ll be able to tell him I love him loud and clear, and not whisper it down the phone like I’m ashamed to say it.’

‘What time?’ Daisy asked.

‘About seven o’clock. He reckoned he’d be back and debriefed by then. The transport to take them to York station leaves at eight, so that’ll give him time to get cleaned up and snatch some breakfast beforehand.

‘The rest of his crew are going to Edinburgh, them being Canadians and not able to get home, poor loves. Tim’s skipper said he was going to spend his entire leave hunting the shops for whisky, and sleeping. Oh, well – I’ll give you a ring tomorrow night.’

She turned away abruptly because she was so miserable, so utterly lonely, and after tomorrow morning it would be worse. Tears filled her eyes and she let them flow unchecked.

Then she turned abruptly as Daisy called, ‘Tatty – I do know what it’s like. Remember I haven’t seen Keth for two years.’

‘Yes, of course. ’Night, Daisy …’

Daisy didn’t know, she thought fiercely; not really.

Okay, so she hadn’t seen Keth for ages but at least she knew he was going to survive the war. Keth was safe in America and tonight Tim would be flying over Germany, searching the sky for fighters. Tim was a tail-end Charlie and tomorrow morning, if Whitley K-King touched down safely, Tim would have flown his thirteenth op. – the dicey one.

She sniffed loudly and dabbed at her eyes. She would not cry. Tim would be all right. Her love would protect him because now they truly belonged. Now Tatiana Sutton was a living, breathing, pulsating woman who loved and was loved in return. No longer was she a cosseted only child, guilty for having been born a girl. She was one half of a perfect whole that was Tim and Tatiana. She existed, when alone, on a soft cushion of disbelief at the new creature she had become. Just to see a flower bud opening or a bird in graceful flight made her feel warm inside.

When the squadron took off from Holdenby Moor into a peachy early-evening sky, she was sick with despair and hugged their love to her like a child with a precious, familiar toy.

When they came together – really together – their first loving had been sweet and gentle and filled with the delight of belonging but the next time had been fierce and without inhibition and if, she thought through a haze of sadness, their last coupling had made a child, then so be it. And if one morning K-King did not come home, then she would have something belonging to him and she wouldn’t care about Grandmother Petrovska nor a shocked Holdenby that would turn away from her and whisper behind her back that she was no better than she ought to be.

But she would never let them take Tim’s child from her. Daisy would understand because Daisy and Keth had been lovers. And Uncle Nathan would help her because he was the kind of man who, if a child could choose its own father then she, Tatiana, would have chosen him.

She wondered if her own father had been kind, like his brother Nathan, and knew instinctively from things half remembered from a misty childhood that he had not.

She closed her eyes. She must not weep again because if she did, someone at home would ask her what was the matter. Instead, she squeezed her eyelids tightly shut.

‘I love you so much, Tim,’ she whispered. ‘Take care tonight.’

‘There, now! See how it’s done, lass?’ Jack Catchpole held aloft a broom handle from which was suspended the hessian sack of hen droppings. ‘You tie the sack in the middle, then you tie it to your broom handle – or any suchlike piece of wood. Is the tub ready?’

‘Ready, Mr C. Half full of rainwater, like you said.’

‘Then that’s all there is to it.’ Catchpole regarded the zinc washtub his wife had discarded all of three years ago. Lily was alus throwing things away. Thank the good Lord he’d had the sense to rescue it from the rubbish tip. He had known he would find a use for it one day. ‘You lay the broom handle across the top of the tub so the sack is covered with water, then every day you lift it up and down – give it a good ponching – and by next year, that liquid’ll be food and drink to those little tomato plants.’

‘Next year? But won’t it smell, Mr Catchpole?’

‘Smell? Oh my word yes, it’ll smell.’ He closed his eyes in utter bliss. ‘There isn’t a scent on God’s earth, Gracie, like a tub of liquid hen manoor.’ Unless it was the wonderful, spring-morning whiff from a well-rotted heap of farmyard manure. ‘Next year’s tomatoes’ll wonder what hit ’em when they get a dose or two of that mixture. Tomatoes big as turnips we’ll have!’

‘But won’t it attract flies – bluebottles and things?’

‘Happen it could, and happen we might cover it up when the hot weather comes. But we’ll worry about that next summer.’ If they lived to see another summer, that was. ‘And till then, I want you to see to the ponching. Every day. The hen manoor will be your responsibility, lass, so don’t forget, will you?’

‘Every day.’ She closed her eyes briefly and shuddered inside her. Stuffed vegetable marrows were bad enough. Never would she eat one she had vowed, and now, just to think of tomatoes grown red and fat and juicy on hen muck made her towny soul writhe. ‘I’ll remember. And while I’m remembering – I won’t be able to go to Lady Helen’s party. Our forewoman told us this morning we’re to go on leave in two lots. Now the corn harvest is in, she said, we’d all of us best take it whilst we could, because soon the farmers will be busy lifting potatoes and sugar beet. Sorry, Mr C. but we’ve got to do as we’re told.’

She did so want to see her family again, tell them about Rowangarth and Mr Catchpole and all the things she was learning about gardening, yet it was a pity, for all that, to have to miss the party.

‘Can’t be helped, Gracie. I’ll miss you, but a week isn’t for ever. And them little hens are going to miss you, an’ all. Who’ll be looking after them?’

‘Daisy said she and her mother would see they got a hot mash every day, and plenty of water, though I bet you anything you like they’ll lay their first egg whilst I’m away,’ she sighed.

She was fond of Mrs Sutton’s six Rhode Island Red pullets, loved their placidity, the way they scratched industriously, their softly feathered bottoms wiggling this way and that. She had almost given each one a name until common sense told her she must not become too attached to them. But it really would be awful if Daisy were to find the first egg in one of the straw-lined nest boxes. In fact, Gracie was forced to admit, she was getting too contented with her new life in the kitchen garden, and seeing seeds she had helped to plant and pot on growing into fine cabbages and sprouts and leeks.

It was going to be awful going back to Rochdale. It would be unbearable were not Mum and Dad and Grandad there. In fact, the only thing good about leaving Rowangarth and Mr Catchpole would be the certain fact that the war was over.

‘Now don’t look so glum, lass. You look as if you’ve lost a shilling and found a penny. Cheer up. It might never happen.’

‘No, Mr C. It mightn’t.’

But it would happen. One day, one faraway day, the land girls and Waafs and the ATS girls would hand in their uniforms and go home and Gracie Fielding would take off her overalls for the last time and say goodbye to this beautiful garden.