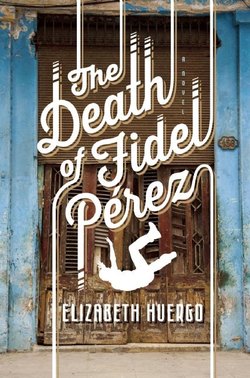

Читать книгу The Death of Fidel Perez - Elizabeth Huergo - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

C H A P T E R O N E

ОглавлениеSome fifty years after the 1953 Moncada Army Barracks Raid, at nearly seven o'clock on the morning of July 26th, and at just the moment when the sun's rays rose magically from the edges of the earth, Fidel Pérez, who had already ingested a quart of Chispa de tren, the cheapest beer his younger brother Rafael had found on the black market, was nursing a badly broken heart. This Fidel, a dissolute, angry Romeo bereft of his tatty Juliet, stepped out onto the balcony that ran the full perimeter of his brother's apartment to face the dawn. Lacking all appreciation for the morning's charms, he belched loudly, raised both fists, and furiously jabbed his middle fingers toward the sun as if it were the miserable slut who had betrayed him the week before. Infuriated at the sun's ambivalence, he leaned over the railing and shouted down at the balcony two floors below his, where he knew the middle-aged Isabel must still be sleeping, her husband beside her.

"¡Isa! ¡Isa, te amo! ¡Isa, eres mia! ¡Mia solamente!"

The alcohol that after a week of drinking allowed him to lower his manly guard and sob openly also slurred his speech. So even Rafael, in the kitchen making coffee, his head splitting in pain, was startled by his brother's sudden patriotic fervor for the isla, the island with which, oddly enough, Fidel seemed so consumed that morning. Rafael had never known his brother to insist so adamantly on how much he loved the isla; how much the isla belonged to him only. Rafael was smiling, having just realized what Fidel was actually shouting about, when he heard the sound of the balcony and its rusted iron balustrade giving way.

"¡Hijo de la gran puta!" Fidel screamed, the hum of alcohol in his brain giving way to terror.

Rafael dropped the hot coffee and ran to the edge of the broken balcony just in time to see Fidel clinging, his fingers wrapped tightly around the balustrade, his body dangling in midair.

"¡Socorro! ¡ Fidel se calló! Help! Fidel's fallen!" Rafael shouted.

Shocked by the fragility of life, in that moment Rafael's cry for help was both practical, an expression of his desire to save the hard-drinking older brother he loved, and incantatory, a plea cast like a magical spell, a wish that this evil fork itself onto a different path and that this terrible misfortune belong to some other Fidel.

Rafael lurched over the broken threshold and grabbed fast to his older brother's forearms. But the weight of Fidel's body was too much, or the strength of Rafael's grip too little, or the decay of the balcony too extensive.

Justicio, their neighbor directly across the street, was carefully wheeling his bicycle cab out of the communal garage on the ground floor when he heard an uncannily familiar voice shouting about his love for the island and then a horrible rending sound he couldn't identify. Justicio looked up just in time to see the Pérez boys falling, in a terrible embrace, tumbling headfirst toward the front garden that had been covered in concrete so many years earlier. He watched their bodies strike the concrete, though it took him what seemed an eternity to absorb what he had witnessed.

The Pérez boys never had a chance, Justicio thought, crossing the street, kneeling before their entangled bodies, and closing their eyes.

"¿Que paso, Justicio?"

" Fidel calló—" Justicio explained, gesturing toward the bodies and the pile of rubble on the ground.

"¿Y este quien es?"

"El hermano."

"¿Los dos calleron?"

" Fidel calló y el hermano tambien," Justicio said.

He knelt sorrowfully by the bodies of the two brothers, still warm, their embrace intact. He watched the neighbors who had heard the commotion flock around the bodies, craning their necks to catch a glimpse of the blood that had begun to drip down from the concrete garden and onto the sidewalk below.

"¡Fidel! ¡Fidel! ¡Dios mio, Fidel!"

No one stopped to consider that Isabel, the woman who had broken Fidel's heart, was addressing the pulpy remains of her latest conquest. There she stood at the center of a swirling vortex of confused people who had become strangely unaware of the brothers' mangled bodies and more interested in the spectacle of Isabel, wailing like a witch bereft of her familiar, her unkempt mane of hair trailing behind her, her arms flailing, and her ample bosom bursting from the grip of a nearly transparent bathrobe as she expressed the anguish of a very good neighbor.

The voices of the onlookers rose in empathy around the inconsolable Isabel, eventually building to a ponderous weight.

"¡ Fidel calló!" a young man shouted from the top of a nearby lamppost that he had managed to climb with some effort.

"His brother, too," Isabel's husband echoed, his enormous, furry belly pressing through the rails of his bedroom balcony.

The crowd below them began to sway and roll under the weight of emotion.

"¡ Fidel calló!" Isabel wept.

"His brother, too!"

"¡ Fidel calló!"

"His brother, too!"

The Pérez brothers, known for nothing in life except the boyish charm that enabled them to cadge most of whatever they needed, now in death began to catalyze an inadvertent turn toward consciousness. The people who heard the commotion early that morning found themselves at a threshold between worlds, suspended for that last aching moment like water coalescing, loosening its tensile grip and then dropping and splattering onto a new surface, much as the body of Fidel and his brother had done.

"What a fitting day for Fidel and his brother to die," someone said.

Justicio, still kneeling by the bodies, looked up. For him, seeing the bodies of the Pérez boys tumbling to their deaths was like witnessing the deaths of his own two sons, or the death of those hopes he had once held in his heart for that generation born on the cusp of revolution. His sons and the Pérez boys— they were stunted, their intelligence yoked to the practical matter of living, of scrambling each and every day to find enough to eat, enough gasoline and parts to make whatever contraption they could get their hands on run another few kilometers. That was all they knew.

"Don't be so offended, hombre." The man grinned. "You have to admit. It's funny. Of all the days of the year. This little dictator and his brother died today, July 26th."

A dark wave of laughter curled through the crowd. Justicio stood up, searching for something to say. Instead he pushed through the crowd and back across the street to the garage where he had left his bicycle cab, his mind drifting, in search of comfort or distraction, and settling unexpectedly on the long-ago image of Fulgencio Batista, his face staring out from the front page of the newspaper. After the Moncada Army Barracks Raid of 1953, Batista had Fidel arrested, tried, and convicted, but he could neither leave him to languish in a prison cell nor kill him. To the Cuban public, Fidel had become a latter-day Robin Hood. So, in order to preserve himself, Batista released Fidel and exiled him to Mexico, never expecting that in 1956 Fidel, alongside his brother Raúl and Che Guevara and seventy-nine other revolutionaries, would return in secret to Cuba. Batista never expected that the peasant farmers along the Sierra Maestra would feed and support Fidel or that the hungriest and the most outraged of the middle class would pour into the streets to welcome him.

In the years between the 1953 Moncada Army Barracks Raid and the Revolution of 1959, as Batista was losing his dictatorial grip on the island, the U.S. continued to insist publicly on its neutrality, all the while supplying Batista's government with arms and military training. In the streets of Havana and other cities and towns across Cuba, men and women were openly clubbed for opposing Batista; prison cells became torture chambers; and police officers members of death squads. The killing and maiming spiraled indiscriminately. The more Batista repressed every grassroots urge for democracy, the more the U.S. buttressed Batista's repression and the more reasonable and noble Fidel appeared. Justicio remembered how Batista's once smug expression disappeared, replaced by the mask that stared out at him from the page: disbelieving, primal, the look of an animal startled, paralyzed by fear. He remembered the dark wave of spite and joy that washed over him; that made him one with the sardonic stranger.

"¡Justicio! ¡Justicio! ¿Que paso?" Irma shouted down to him frantically from an open window.

" Fidel and his brother have fallen," Justicio shouted back, not an ounce of emotion in his voice.

"¿ Donde vas?" Irma shouted, upset that he was leaving.

Justicio made believe he hadn't heard her and began pedaling away. He didn't want to stay. There was nothing he could do. All he wanted was to leave the past, to leave calamity far behind him and to concentrate on how he would feed his family today. He didn't care that it was July 26th, he told himself. As for the sacrilegious stranger, Justicio knew he was no better.

Much like Justicio, some of the good citizens who overheard the sardonic stranger that morning were quite old, as old as the Moncada Barracks hero of 1953 they re membered so well. Gathered there in the street, fearful of change, they could still remember something that had come before this surface they had grown so accustomed to, clinging mindlessly, day after day, until the days had grown into years and the years into decades. For others in the crowd, the 1953 raid was a vague legend. They were so young that Fidel's fall today triggered only a cascade of possibilities, possibilities so enticing that there was no such thing as fear or death or unmitigated suffering. Still others were approaching middle age, and the awareness of their mortality, not as an abstraction but as something visceral, felt in the bone and sinew, had already begun to form its own critical mass, rising within them like an unrelenting tide. Whatever dreams they once had were drained away, revealing the underlying rock, the certainty that time had rendered their passivity into inadvertent choices, while the actual lives they had once imagined had been left unlived and far behind.

At that precise moment, the unexpected and indecorous joke exacerbated a breach between what they had all tacitly accepted and what they all understood and desired. Their laughter transformed each of them, young and old and in between, into conspirators who shared the same hopes. They recognized one another. The decades of be ing separated had passed and were beyond repair, but now the bond among them was irrevocable, the cumulative energy of their response drawing them together with a force as great as gravity, rising to an enormous crest, then shattering over their regrets.

One particular good citizen, Saturnina, was squatting on a doorstep just a few blocks away, feeding a hard biscuit to a hungry stray dog, when she heard the news that Fidel and his brother had fallen. Saturnina rose from her corolla of ragged skirts and began to walk toward the throng of people gathering before the building and spilling over into the street, blocking the morning traffic. Though she could see nothing of what had happened, in a swirl of petticoats and skirts she began to mimic the words she heard:

"¡Socorro! ¡ Fidel calló! Help! Fidel has fallen!"

Saturnina, Sybil of the succulent bit of news that lodges like a string of pork gristle in the space between back teeth, began to fidget and whirl her way through the edges of the gathering crowd, calling out what she had instantly accepted as fact: The apocalypse that would precede the return of her son Tomás, whom she had lost decades earlier in the violent interregnum between Fulgencio Batista and Fidel Castro, had begun.

"¡ Fidel calló! His brother has fallen, too!"

Stepping and swirling, the old woman tripped along the farthest perimeter of the bloody scene. As she passed along the streets calling out her news, housewives peered through rusted iron rails, pulling back quickly into darkened interiors. Men and women on errands or on their way to work or school stopped to listen, then sped on, looking back over their shoulders nervously.

"What did that old woman say?"

" Fidel has fallen!"

"The old man is gone? "

"Yeah, his brother, too."

"You sure? "

The news of Fidel's death began to travel like molten rock down a mountainside, obliterating everything in its path and transforming itself from liquid to solid by the time it reached the entrance to the University of Havana.

"What are they saying about that sick old man? "

" Fidel is gone!"

"What about Raúl? "

" Fidel is Fidel. Fidel can't be replaced."

"I'm telling you they're both gone."

"The government has collapsed? "

"Gone in a single stroke."

The lava swirled and eddied as it traveled down the

long avenues, oozing past statues of nineteenth-century generals and plazas spotted with bronze plaques. Spreading, the news flowed down the white marble avenues, the broken cobblestone streets, the flanks of crumbling mansions, brittle vestiges of a colonial life suspended now, like the forgotten rags hanging on frayed clotheslines attached between archways and windows.

The shocking news that Fidel and his brother had both been killed coincided with the weekly rolling blackout across parts of Havana, a practice instituted by the government to save precious electricity. Now that blackout was adding to the fear. What had become to most Habaneros an habitual nuisance quickly took on a foreboding quality. Fidel and his brother had fallen, and so had the city descended into a metaphorical darkness on that bright July morning.

The Habaneros who heard the rumors and still had electricity turned to the government radio and television stations, which that very morning had been shut down for a series of upgrades. Those upgrades had been deferred, month after month for more than a year, until the day before, when a team of Italian technicians had arrived in the city and begun to test the emergency-band frequency. So when those citizens tuned in expecting to be told that, at the very least, Raúl Castro was well, or that Fidel was fragile but holding on to life as any old man with too much power would, they heard instead a high-frequency screech, an angry bionic grasshopper, harbinger of dread and pestilence and things easily imagined by people who have nothing left in this material world.

Saturnina's cry continued to resonate along the streets, buttressing the old woman and lending her words a factual quality that belied her exhaustion. To the university students on their way to class, she seemed no more an anomaly than the mongrels that wandered from door to door or the obsolete tank on the central quadrangle of the University of Havana, Fidel's iron Rocinante, the very tank on which he had ridden into the heart of the city in 1959, only six years after the Moncada Army Barracks Raid, an event that had been dismissed at the time as a thing of no consequence, the magical thinking of puerile misfits, by the pundits who considered themselves the best sort of historians.