Читать книгу Munch - Elizabeth Ingles - Страница 3

ОглавлениеThe name Edvard Munch conjures up, for most people, one irresistibly memorable picture: The Scream, a shriek of stomach-churning terror uttered by a cringing figure with a skull-like face outlined against a fiery, blood-red sunset. This iconic image has come to epitomise the angst embodied in the Expressionism of the late 19th century.

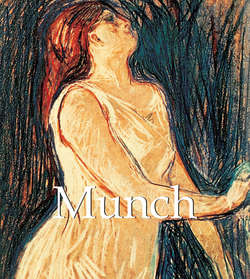

Self-Portrait

1881–1882

Oil on paper glued to cardboard, 25.5 × 18.5 cm

Munch Museum, Oslo

Yet its creator, a gentle soul given to introspection and self-analysis, lived to see his eightieth birthday and witnessed the world-wide critical acceptance of the Expressionist movement which he was largely instrumental in initiating. Somehow one imagines that the originator of so graphic an image of fear would be too delicate and unworldly to survive the violent upheavals of the early 20th century, but, although he suffered terribly from depression and anxiety for the greater part of his life, Munch was able to find a mode of living that enabled him to produce a large body of psychologically penetrating, disturbingly beautiful work. He was born in 1863 to a frail young mother, Laura Bjølstad, and her older husband, Christian Munch, a doctor; the following year the family moved to Christiania, as Oslo was then called.

Old Aker Church (Gamle Aker kirke)

1881

Oil on canvas, 16 × 21 cm

Munch Museum, Oslo

Karen Bjølstad in the Rocking Chair

1883

Oil on canvas, 47 × 41 cm

Munch Museum, Oslo

There were five children altogether, of which Edvard was the second-born and eldest son. Early on, Munch understood that he had a difficult two-fold heritage to contend with: the physical threat of tuberculosis, which first carried off his mother and then his elder sister, and the faint but distinct possibility of mental instability. Laura Munch died at the age of thirty, shortly after the birth of her fifth child.

My Brother Studying Anatomy

1883

Oil on cardboard, 62 × 75 cm

Munch Museum, Oslo

The effect on the family may be imagined. The father suffered most acutely, the younger children carrying only the haziest memories of their mother into later life. But the consciousness of loss never left them.

His father’s religiosity became more pronounced after Laura’s death, to the point where the children’s anxiety about offending against Christian principles instilled in them a palpable fear of eternal damnation.

Girl Lighting a Stove

1883

Oil on canvas, 96.5 × 66 cm

Private collection

The unhappiness of his childhood experience of death was compounded by his father’s unpredictable behaviour. Munch and his brother and sisters were never quite sure how their father’s fanatical piety was going to manifest itself – but they could rely on the fact that they would be made to feel inadequate either as dutiful Christians or as obedient children.

Morning (A Servant Girl)

1884

Oil on canvas, 96.5 × 103.8 cm

Private collection, Bergen

At times Dr Munch’s playful nature, suppressed almost totally by his sadness at the death of his young wife, would resurface briefly and he would play with his children like any normal father. But then the blackness would reassert itself, and he would lash out violently.

Portrait of the Painter Karl Jensen-Hjell

1885

Oil on canvas, 190 × 100 cm

Private collection

Indeed, in later life Munch would write that his father became almost insane for short periods. This must have been quite terrifying for a sensitive, quiet young boy who was himself prone to frequent bouts of illness. The death of his sister Sophie, the eldest child, when Edvard was thirteen, caused him even more profound suffering than had the loss of his mother when he was five.

Tête-à-tête

1885

Oil on canvas, 66 × 76 cm

Munch Museum, Oslo

He watched anxiously as his father prayed over the girl, unable to do anything for her. To him, and to Sophie, Dr Munch’s promises of eternal heaven meant nothing compared with her burning desire to live.

Her struggles were unbearable to watch. Edvard’s utter helplessness and sorrow were channelled some years later into a painting that he returned to obsessively: the marvellous The Sick Child, the first version of which was executed in 18851886. (There were to be six versions altogether, created at roughly ten-year intervals.) In this large painting, almost four feet square (120 cm), he struggled throughout his life to express what he felt so intensely about his sister’s death.

Self-Portrait

1886

Oil on wood, 33 × 24.5 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

The Spring

1889

Oil on canvas, 169 × 263.5 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

During her last illness she repeatedly pleaded for help, for relief from pain – neither Edvard nor his doctor father was able to provide it. This incapability was transformed into a feeling of guilt that he had survived and she had not. His attempts to put himself in her place in the picture were doomed to failure, just as he had failed to take her place as she lay dying. To the end of his life he was unable to resolve this.

Portrait of the Author Hans Jaeger

1889

Oil on canvas, 109 × 84 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

His guilt is poured into the picture, which is almost unbearably poignant. The young girl’s face is already a ghost, almost disembodied as she silently yearns to go on living. With its deep layers of meaning and evocation of the state of the artist’s soul, this can fairly be termed one of the first Expressionist paintings.

Spring Day on Karl Johan Street

1890

Oil on canvas, 80 × 100 cm

Bergen Billedgalleri, Bergen

He himself termed it ‘a breakthrough’ in his style, and the collector and critic Jens Thiis, later Munch’s biographer, called it ‘the first monumental figure painting in our Norwegian art’.[1]

The emphasis on religious piety (which appeared to not do the slightest good, as prayers for the life of mother and sister went unheeded), and the authoritarianism of a father who punished disproportionately for the most minor transgressions, came together in Munch’s mind to give him a view of God as unjust, full of anger, and entirely without compassion. Although he did not dare to contradict his father by refusing to go to church, by the time he was in his early twenties he had reached the conclusion that God did not exist, and that there was no eternity.

Night in St Cloud

1890

Oil on canvas, 64.5 × 54 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

The Seine at St Cloud

1890

Oil on canvas, 61 × 49.8 cm

Gift from Mrs Morris Hadley (Katherine Blodgett class of 1920), 1962

The Frances and Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York

This belief in the non-existence of God remained broadly unaltered throughout the rest of his life, though he changed his mind about the possibility of a continued existence in a kind of afterlife. With some bravery, Munch took the decision to become a painter in the face of his father’s firm preference that he should study engineering. His father reluctantly acceded, on the advice of a draughtsman friend.

Melancholy

1891

Oil on canvas, 72 × 98 cm

Private collection

One of Munch’s earliest self-portraits, from a year or so later (Self-Portrait, 1881–1882), shows a young man of sensitive, even sickly aspect, his large pale face, full curving lips, and sloping shoulders giving little cause to credit him with any kind of physical or mental toughness. Yet there is, in the clear gaze, something of a challenge to the onlooker who might thus dismiss him.

Woman in Blue against Blue Water

1891

Oil on canvas, 99 × 65.5 cm

Private collection

After their mother’s death, the children were comforted a little by the advent of her younger sister Karen, who came into the family and took over as housekeeper and governess. She had done some dabbling in painting herself, and quickly came to recognise that Edvard had an unusual talent. Later in life, he greatly valued her encouragement, although at first he did not appreciate it as much as he might.

Rue de Rivoli

1891

Oil on canvas, 81 × 65.1 cm

Gift from Rudolf Serkin, 1963, Harvard Art Museums

Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

A portrait of his aunt painted in 1884 (Karen Bjølstad in a Rocking Chair) goes some way to making amends – the calm young woman is portrayed sitting in the window, gently rocking herself. His portraits of this period are strikingly mature, particularly that of his sister Inger, which reveals a young girl with great strength of character in her sombre, slightly averted gaze (Inger Munch, 1884).

Melancholy

1892

Oil on canvas, 64 × 96 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

Norway was an artistic backwater at this time – the few major painters of the period included Christian Krohg, Frits Thaulow, and Erik Werenskiold, who formed the native school, with its keynote of naturalism. They mounted their first Autumn Exhibition in 1882, beginning a regular series that at first met with much critical disapproval.

Moonlight on the Coast

1892

Oil on canvas, 62.5 × 96 cm

Private collection, Bergen

Manet was their idol, their lodestar. Munch embraced this group warmly, and in the course of some months was taught how to use colour by Krohg. However, he felt he had to go abroad to gain the stimulus and training he needed. In 1885, he was enabled to go to Paris thanks to the generosity of Thaulow, a frequent supporter, and grants from various bodies.

Portrait of Inger, the Artist’s Sister

1892

Oil on canvas on wood, 172.5 × 122.5 cm

Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

Thaulow – Gauguin’s brother-in-law, as it happens – not only gave him moral and financial support in the face of critical hostility, but also bought one of his earliest successes, Morning (A Servant Girl) of 1884.

Before he left for Paris, Munch met the woman who was to cause him perhaps the deepest grief and psychological damage of his emotional life: Emilie (Milly) Thaulow.

Summer Night / Inger at the Beach

1889

Oil on canvas, 126.4 × 161.7 cm

Rasmus Meyers Collection, Bergen Art Museum, Bergen

He was now twenty-two; she was twenty-four, married to his cousin Carl, and with no moral scruples about engaging in an adulterous affair. She was beautiful and blonde in a classic Scandinavian way, and admirers flocked round her. She toyed with Munch, who fell heavily for her. At first they enjoyed a lovers’ idyll, but he was unable to retain the interest of this sensual and amoral woman for long.

Evening on Karl Johan Street

1892

Oil on canvas, 85.5 × 121 cm

Rasmus Meyers Collection, Bergen Art Museum, Bergen

Munch continued to show work at the regular Autumn Exhibitions in Oslo, but the critics took not the slightest notice of his offerings at the 1887 show. Feeling neglected and slighted professionally, he was reduced to a state of deep neurosis when he realised that the experienced Milly was not after all faithful to him.

The Author August Strindberg

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу

1

Quoted in J. P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, World of Art series, London 1972, p. 22.