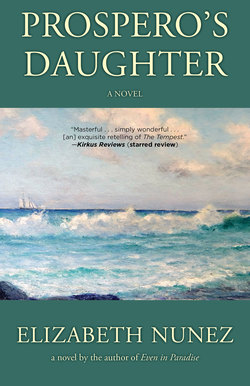

Читать книгу Prospero's Daughter - Elizabeth Nunez - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

He tell a lie if he say those two don’t love one another. I know them from when they was children. They do anything for one another. I know. I see them. I watch them. I tell you he love she and she love him back. They love one another. Bad. He never rape she. Mr. Prospero lie.

Signed

Ariana, cook for Mr. Prospero, doctor

JOHN MUMSFORD put down the paper he had been reading and sighed. He did not want the case, but the commissioner had assigned it to him. Murder and robbery were the kinds of crimes he preferred to investigate. Hard crimes, not soft crimes where the evidence of criminality is circumstantial. He preferred a dead body, a ransacked house, a vault blown open, jewels and money missing, tangible evidence of wrongdoing, not cases that depended on her word against his word.

In 1961 no one had figured out that dried sperm on a woman’s dress could be traced irrefutably to its source, at least no one in the police department in Trinidad. So as far as Mumsford was concerned, notwithstanding the fact that there could be some damage to the woman—torn clothing, scratches on the body, sometimes blood—these matters of rape were better handled as domestic quarrels, some of which could certainly end in murder, but in the absence of murder, not worth pursuing. In the end, there was always a persuasive argument to be made about a woman dressed provocatively, a woman alone, in the wrong place, in the dead of night. A woman flirting. A woman asking for it.

There was the case the week before, buried in The Guardian on the fifth page. A black woman from Laventille had filed a complaint with the police claiming that her fifteen-year-old daughter had been gang-raped in a nightclub in Port of Spain by three American sailors who had locked her in the restroom and stuffed her mouth with toilet paper. The reporter presented the facts as they were apparently given to him by the mother of the fifteen-year-old, but he went on to comment on the sad conditions of life for the residents of Laventille: “Houses, no hovels,” he wrote, “packed one on top of the other, garbage everywhere, children in rags, young people without hope, dependent on charity. It’s no wonder.”

That “no wonder” set off a deluge of letters to the newspaper. Four days later, on its second page, The Guardian printed three. “A wonder, what?” one person wrote. “A wonder that her mother wasn’t in the nightclub also selling her body? What do those women expect when they dress up in tight clothes and go to those clubs? Everybody knows the American sailors go there for cheap girls. She had it coming. How could her mother in good conscience call what happened to her daughter rape?”

That seemed to be the consensus of God-fearing people on the island. Soon witnesses surfaced who swore they had seen the girl the night before with the same three sailors.

Mumsford agreed with the consensus: The girl had asked for it. Yet for no other reason than that the hairs on the back of his neck stood up at the mere mention of Americans, he also believed that the sailors had taken advantage of her.

It was a matter of schadenfreude, of course. Mumsford was English, and though he readily admitted his country had needed the Americans during the war, they irritated him. They were too boisterous, too happy-go-lucky, he thought. They waved dollar bills around as if they were useless pieces of paper; they laughed too loudly, got too friendly with the natives.

Trinidad’s black bourgeoisie didn’t approve of the Americans either, but they knew it was the English colonists who had given them this leave to swagger into town as if they owned the island. Which, indeed, they did, partially, that is, when the British gave them Chaguaramas, on the northwest coast of the island, not far from the capital, Port of Spain, to set down a naval base, and then Waller Field in central Trinidad, for the air force. It helped that the British explained that they needed the twenty battleships the Americans offered in exchange, but not enough to quell rancor in some who were making the American military bases a cause célèbre in their demands for independence.

Still, the simmering resentment of the American presence, shared by both the colonizers and the colonized, though for different reasons, was not enough to gain sympathy for the girl. How could it be rape when she was dressed like that, a fifteen-year-old girl with her bosom popping out of a tight red jersey top, and a skirt so short that, according to the nightclub owner, you could see her panties?

But, of course, the case the commissioner had assigned him was different. The woman in question, the victim, was English; the accused, the perpetrator, the brute, was a colored man.

The commissioner himself had come down to the station where Mumsford was posted and had spoken to him in private. “Mumsford,” he said, “you are the only one I can trust with this job.”

The job involved going to the scene of the crime, Chacachacare, a tiny, desolate island off the northwest coast of Trinidad, where the reputed rape had occurred, and taking the deposition of Dr. Peter Gardner, an Englishman, who had lodged the complaint on behalf of his fifteen-year-old daughter, Virginia.

“It is a delicate matter, you understand,” the commissioner said. “Not for a colored man’s ears or eyes.”

The commissioner was himself Trinidadian. He was born in Trinidad, as were his parents and grandparents and great-greatgrandparents. He was what the people in Trinidad called a French Creole. He was white. That is, his skin was the color of what white people called white, though it was tanned a golden brown from generations in the sun. Local gossip had it, though, that none of the white people in Trinidad whose families went back so many generations had escaped the tar brush, and indeed the telltale signs of the tar brush were evident in the commissioner’s high cheekbones, his wide mouth and full lips, and in the curl that persisted in his thick brown hair. These features made him handsome, but skittish, too, for he had a deep-seated fear of being exposed, of finding himself in good company confronted by a man whose resemblance left no doubt that he was a relative with ancestors who had come from Africa.

The French had come in 1777 at the invitation of the king of Spain, who had neither the time nor the inclination to develop the island, one of the smallest of his “discoveries” in the New World. Preoccupied with the more alluring possibilities of gold in El Dorado on the South American continent, the king opened Trinidad to the French, who already had thriving plantations on the more northerly West Indian islands, thanks to slave labor from Africans they had captured on the west coast of Africa. The Spanish king thought he had struck a clever bargain, a cheap way to clear the bush in Trinidad while he was busy with weightier matters. The French brought thousands of African slaves to Trinidad from Martinique and Guadeloupe. Twenty years later, in 1797, the British seized Trinidad from the Spanish, but the French stayed on, claiming ownership of large plots of land, even after Emancipation in 1834.

Mumsford knew something of this history. He knew, too, that though the French Creoles on the island were linked to the English by the color of their skin, they were, nevertheless, culturally bonded to the Africans in Trinidad who had raised their children. More than once this knowledge had caused him to wonder whether, in a time of crisis, he could count on the commissioner’s loyalty. Would he side with the English, or would he suddenly be gripped by misguided patriotism and join forces with the black people on the island? He was always a little put off by the commissioner’s singsong Trinidadian English, though he had no quarrel with his grammar. On the question, however, of how to respond to Dr. Gardner’s allegation, the commissioner put him completely at ease.

“Only we,” the commissioner said, stressing the we and sending Mumsford a knowing look that sealed his trust, “can be depended upon with a matter of this delicacy. Don’t forget, Mumsford, that girl, Ariana, has already come up with her own lies and can make a mess of this for all of us.”

Us. The commissioner had a French-sounding last name, but Mumsford was satisfied that he was on his side.

Mumsford picked up the paper he had shoved aside and read Ariana’s statement again. He never rape her. She had written she, not her, but he could not get his tongue to say it. Dropping the d from the verb was bad enough.

“Attempted rape, not rape,” the commissioner had cautioned him. “In fact, Mumsford,” he said, “if you can avoid using that word at all, so much the better. We can’t have that stain on a white woman’s honor.”

And so it would have been—the nightmare of any red-blooded Englishman who had brought wife, daughters, sisters to these dark colonies—had that man, that savage, managed to do what no doubt had been his intention.

He had to remember to be careful then. It was not a rape, not even an attempted rape. There was no consummation. He must not give even the slightest suggestion that consummation could have been possible, that the purity of an English woman, that her unblemished flower, had been desecrated by a black man.

The woman, Ariana, had not put her letter in an envelope. She had glued together the ends of the paper with a paste she had made with flour and water. Mumsford was sure it was flour and water she had used, not store-bought glue. He was there when the commissioner slit open the letter. The dried dough, already cracked, crumbled in pieces, white dust scattering everywhere. He had leaned forward to clear the specks off the commissioner’s desk and was in mid-sentence, rebuking Ariana for her lack of consideration for others—“What with the desk now covered in her mess”—when the commissioner interrupted him. It was good she had sealed it, whatever she had used, the commissioner said. They needed to be discreet. Then he paused, scratched his head, and added, “Though there is no guarantee she has not told the boatman. People here talk.” He wagged his finger at Mumsford. No, they had to nip this in the bud. If they were not careful, the whole island would soon be repeating her version of what had happened on that godforsaken island. Soon they would be whispering that a white woman had fallen in love with a colored boy.

“ ‘I tell you he love she and she love him back.’ ” The commissioner read Ariana’s words aloud. He threw back his head and laughed bitterly. “A total fabrication,” he said. “How could it be otherwise?”

Mumsford did not need convincing. They love one another. Bad. That had to be a lie.

But it was not only Ariana’s reference to rape and the pack of lies she wrote in defense of the colored boy that irritated Mumsford this morning. It was also her presumption—what he called the carnival mentality of the islanders, their tendency to trivialize everything, to make a joke of the most serious of matters, turning them into calypsos and then playing out their stories in the streets, in broad daylight, on their two-day Carnival, dressed in their ragtag costumes. Yes, an English doctor of high repute would be addressed as Mister, but he was sure Ariana did not know that, and certain that she knew that the doctor’s name was not Prospero, but Gardner. He was Dr. Peter Gardner—Gardner, a proper English name—not Mr. Prospero, doctor, as she had scrawled next to her name.

Ordinarily Mumsford would have left it at that, dismissed the name Ariana had given to Dr. Peter Gardner as some unkind sobriquet, loaded with innuendo, taken from one of those long-winded tales the calypso-rhyming, carnival-dancing, rum-drinking natives told endlessly. For Prospero had no particular significance to Mumsford, though he had guessed correctly that it was the name of a character in a story. What story (it was a play by Shakespeare, his last) he did not know. Mumsford was a civil servant who had worked his way through the ranks of Her Majesty’s police force. Like all English schoolboys he had read Charles Lamb, not the plays, and then not the story about Prospero. Nevertheless, he was on a special assignment and could leave nothing to chance. He had the honor of an Englishwoman to protect. So he made a note to himself to question Ariana. Question for Ariana, he wrote in his notebook. Why do you call Dr. Gardner Prospero?

He would have to speak to her separately, not in the presence of Dr. Gardner. That was the directive from the commissioner. Mumsford would have preferred otherwise. He wanted to expose her in front of Dr. Gardner for the liar she was, but when he argued his point, the commissioner stopped him. “I don’t think that would be wise,” he said.

For a brief moment, the tiniest sliver of a gap opened up between the Englishman and the French Creole. Would he, in the end, choose them over us? the Englishman wondered. For they could not always be depended upon to be grateful, even the white ones born here. The man stirring up trouble in the streets of Port of Spain with his call for independence was not grateful. And yet there were few on the island that England had done more for. England had educated him, England had paid his way to Oxford, but when he returned to Trinidad, the ungrateful wretch bit the hand that fed him: Independence now! Thousands were gathering behind him.

“You mean Eric Williams?” he asked the commissioner.

The commissioner ignored the question but he winked at him when he said, “We’ll have time sufficient to deal with the girl.”

Was the wink conspiratorial? Did he mean that England still had time in spite of the ravings of this troublemaking politician?

Mumsford tried again. “This is still a Crown Colony,” he said.

The commissioner slapped him on the back. “Let’s not cause the good doctor more grief, okay, Inspector?”

Mumsford had to be satisfied with his response, for the commissioner kept his hand firmly on the small of Mumsford’s back and didn’t remove it until he had walked the inspector out of his office.

But though Mumsford could not say with certainty whether or not the commissioner sided with the Crown or with the burgeoning movement for independence, on the matter of race the commissioner had made himself clear. He would protect a white woman from malicious insinuations. Mumsford was to go alone to Chacachacare without his usual police partner, who was a colored Trinidadian, and, therefore, as the commissioner pointed out, could not be trusted to be objective.

“He will take the side of the colored man against the English girl,” he said to Mumsford without the slightest trace of irony. “You’ll have to do this alone.”

Mumsford shut his notebook and reached for the official statement the commissioner had prepared for the press just in case Ariana had been indiscreet. He had placed the statement next to his brass desk lamp with the bottle-green glass shade, along with two sharpened pencils and his navy blue Parker fountain pen, which he had filled earlier that morning with black ink in preparation for the notes he would take later when he arrived in Chacachacare. Carefully, and reverentially, he unfolded the paper. It was the original copy. It bore Her Majesty’s seal and was typed in blue ink on expensive ivory linen stationery. In the official statement, the commissioner had avoided the word rape altogether. Instead, he had written attempted assault. He had not named the victim, referring to her only as “a young, innocent girl, a fresh flower, an English rose,” but he had identified the assailant: “Carlos Codrington, a colored man on the island of Chacachacare.”

Mumsford’s pencil-thin lips curled downward, an inverted U on a face on a cartoon, and he shook his head in disgust. Carlos Codrington. They were two names, he was sure, which would never be found together in his beloved England. But, as he had resigned himself to accepting, he was not in his beloved England. He was here, on this mixed-up, smothering, suffocating, sultry island, on this stifling, godforsaken, mosquito-ridden, insect-infested, sweat-drenched outpost, with its too, too bright colors, its too, too much everything: too much rain in the rainy season, too much sun in the dry season, too much blue in the sky, too much green in the grass, too much red in the creeping flowering plants, too much turquoise in the sea, too much white on the sand. Too, too many black people. And here there would be a Codrington who was a Carlos.

Mumsford had not come to Trinidad for the black people, of course. He came for the sun, the warmth, when the thought of another winter, another month of gray skies, of the perpetual drip, drip of rain and the smothering fog in England, threatened to drive him insane. These days it often crossed his mind that he had indeed gone crazy, mad, to think this would have been better. This would have been what he needed to end the ceaseless colds that pursued him season after season in Birmingham, and the damnable pollen in the spring that found its way always to his sinuses, leaving his eyes bleary and itchy, his nose red and runny.

The muscles at the base of his head formed a knot, and he reached for the pair of silver tongs his housekeeper had placed on a silver tray on his desk, as she did each morning before he left for work, along with a crystal bowl filled with ice cubes, an empty glass, and a pitcher of water. He was a fairly young man, not much over thirty, slender, but already with a middle-aged paunch from too many beers in the pub after work. He had thick, light brown hair, a neatly trimmed mustache, hazel eyes, and a complexion that was naturally ruddy, his cheeks rosy as apples in England, though here, under the constant sun, sweat dampening his face no matter how often he mopped it with his handkerchief, he looked baked, or, rather, boiled, his skin a startling pink as if it would erupt.

And it was startling pink now as he thought of the brochures that had lured him here, pictures of happy English families frolicking on the beach, their blond hair swept by tropical breezes, which he knew now to be either blisteringly hot or so thick with moisture they would hardly have been able to breathe.

Wielding the tongs between his fingers, he lifted two ice cubes out of the bowl, dropped them in the glass, and filled it with water. His head was throbbing. Behind God’s back, that’s where he was. They should be shot, lined up one next to the other in front of a firing squad, those liars who wrote those ads, who ensnared innocents like him to this outpost.

He had jumped at the chance to escape England’s soggy weather when he was offered the post of assistant to the commissioner of police in Trinidad, and since he was an only child and his father was dead, he had brought his mother with him.

“The sun is not the only advantage,” the recruiting officer had pointed out to him. When he looked puzzled, the officer clarified. “You can improve your class, your station in life. In the colonies, young man, every Englishman is a lord.”

Yes, Mumsford thought, remembering, the Empire was still standing, crumbling, weakened at the knees—they had lost India, most of China, Africa was slipping from their hands, and there were rumblings in the West Indies and the East Indies—but there were still years left for an Englishman in the colonies.

He brought the glass to his lips and drained it. The cold water coursing through the heat in his chest felt good. The knot in the back of his head loosened. He had to admit it: Aside from the sun and the crawly things, he lived like a lord—housekeeper, cook, chauffeur, gardener, a house with three bedrooms, an English car with leather seats, tennis and ballroom dancing at the Country Club, tea at four at Queen’s Park Hotel, golf at St. Andrew’s, yachting down the Grenadines. He began to feel better, his nerves soothed, as they had been soothed in the past, by the realization that it was not all a loss. There was much to gain. Why, last month, for example, there was an invitation to cocktails at the Governor’s House when a relative of royalty was visiting. What stories he would have for the people back home in his English village! He, Mumsford, rubbing shoulders with royalty! The sickening humidity and the too, too bright colors were almost worth the sacrifice. He gathered the papers on his desk, his mood much improved. He had a job to do and he would do it well. The brute, after all, was Carlos, not Charles. A dead giveaway.

He was practically smiling when he bent down to put his papers in his briefcase, consoling himself with his conviction that even without meeting this Carlos, anyone who mattered would know “he was not one of us.” Charles Codrington would have made perfect English sense; Carlos Rodriguez would have been logical. But Carlos Codrington? He was still mumbling happily to himself, reassured by the false comfort he had given himself, when he saw the ants, tiny little russet ones, so small as to be almost invisible, crawling up the sides of his briefcase, from a brown trail that began at a quivering mound in a corner of the mahogany wood floor, and his mood swung back. He had done it again. Last night, tired, his head reeling from more alcohol than he should have had, he had left the briefcase on the floor—a habit he had not broken from his life in England.

It was probably no more than a crumb or a speck of jelly from a tart. In England it would lie there until someone had noticed it. Here, in an instant, an army of ants appeared out of nowhere. His mother no doubt had had her tea in here. He had warned her. Drop the tiniest spot of food and in seconds they would swarm over it. Peel an orange, put it down, turn away for just a few minutes, and they would materialize. In the wet season, they were bigger, fatter. After a rainstorm, some grew wings. At night, they flitted around his bedside lamp before landing on the walls, their flimsy new-made wings fluttering nervously. In the morning, the floor was covered with them, their wings discarded, their bodies like tiny cargo trains, carriages and all, heading toward the next pickup, the next port of food. He had made it a practice to check for them, especially for the tiny russet ones that were the most insidious. Often he would find them when it was too late, when he had already opened a book and they had crawled down its spine into the shafts of hair on his arms, when they were in the folds of the papers he had put into his briefcase. Or when, after he had put on his pajamas and was safely under his mosquito net, they would scoot up his back like thieves, their tiny legs tingling his skin.

This was not a place, Mumsford had discovered, where a man could go to the lavatory in the dark. In the daylight, spiders, lizards, centipedes, water bugs, cockroaches hid in the crevices near the pipes in the bathroom, but at night, they were everywhere: next to the sink, next to the lavatory where more than once a water bug had scuttled across his bare feet when he was sitting down, his pants at his knees, his bare bottom exposed, his legs tucked under unprepared for flight. He had learned, finally, from these unpleasant experiences not only to turn on the light but to wait behind the closed door, even if his bladder was bursting, giving them time to scatter back to their hiding place.

Last week, just as he was stepping into the shower, naked as he was born, he was attacked again. A thing had fallen, or jumped, from the ledge of the window near the shower, onto the shower floor. Splat! He heard the disgusting sound. It was not a water bug. It was larger and uglier than a water bug, six inches long, with a multitude of feet.

It was the two fangs—he was sure they were fangs—jutting out of its head that caused his heart to lurch and the veins in his neck to flood and bulge out thick. He flew out of the house, barely managing to wrap a towel around his waist, which nevertheless loosened when he clutched the gardener by his shoulders, exposing his soft penis nestled against a scraggly bush of long, thin red pubic hairs.

“Is just a millepatte, sir.”

Terrified, but humiliated also by the gardener’s casual response to the fear that gripped him (not to mention the exposure of his penis, which he was certain would become fodder for gossip), Mumsford could only stutter out a command: “Get it out of here!”

But the gardener’s face broke into a wide grin. “Is your lucky day, sir. Kill it, sir. Is good luck, sir, when you see a millepatte yourself, sir. You get plenty money if you kill it yourself, sir.”

It took all of Mumsford’s English stiff upper lip to get the gardener to understand he wanted the thing removed from his bathroom. Now!

He would learn later that a millepatte, as his gardener called it, was a kind of scorpion. If it had stung him, he would have been in the hospital burning with fever. He could have died. But it was a millepatte to his gardener, a lucky charm, called simply millepatte because of its many feet. Mille, the word for a thousand in French.

How they remembered everything, these people, though they never got the history right! Their capital was Port of Spain, but England had won her wars with Spain more than three centuries ago. They had villages with names like Sans Souci, Blanchisseuse, and Pointe à Pierre and yet the French were never their colonizers. Their singsong sentences ended with oui, which, at first, though it made no sense to him, Mumsford understood as we: I tired, we. I gone, we. Then he found out that it was oui. Oui, as in the French, meaning yes.

In the country districts, they spoke a patois, French laced with some African words they remembered and the English imposed on them. They had Amerindian and African blood in them, and though Mumsford shivered to think of it (but he knew what had happened in those battles for conquest of these islands, and in the days of slavery), they had European blood in them, too—Spanish, French, Dutch, and, as he was forced to admit, English.

Now it was fashionable: the impurities. Now, the days long gone when his people could pick off the best of them, the prettiest, and she would lie down for the man who had ordered her to, who had demanded, because he was master, because she was his slave and had no choice, the tables were turning. They would choose. Carlos, the colored boy with the English last name, would choose, would think he could choose. The chief justice would choose, the chief medical officer would choose. They would think they could pick out the prettiest, the best. They could marry an English rose.

For that was what they had both done, the black chief justice and the black chief medical officer. His mother was with their wives that very morning, at the Country Club, playing croquet as if nothing had changed, as if it were natural, the normal evolution of things, that black men would marry white women now that England was about to relinquish yet another colony (indications were everywhere in Trinidad), now that her reign was about to end. But it would never be normal for him. Never for him.

I tell you he love she and she love him back. He would see about that. He would trap that lying Ariana.

Mumsford brushed the last of the ants off his briefcase. He was ready to go. He pulled up his khaki knit high socks over his pink calves, adjusted the wide brown leather belt on his khaki shorts, patted the gleaming buttons on his well-pressed khaki shirt, lifted his stiff khaki policeman’s hat off the hat rack, checked it for ants before putting it on his head, picked up his polished dark brown policeman’s baton, gave himself a last look over in the mirror, made a soldier’s right turn for Good Old England, there, in his drawing room, to the surprise of no one, not to his housekeeper, and certainly not to the driver who had come to collect him, and marched down the steps.

Left, right. That was what he did to show his loyalty to England before this ungrateful lot, biding their time until he was gone, until all the English were gone. Well, let them have it. He, for one, would not be sad to see independence come. Let them have the whole damn place, damn insects and all, damn miserable, stifling weather, damn mixing of bloods. Bloody impurities.

March. He would march down the steps. He was wearing Her Majesty’s uniform.

“Mr. Inspector, sir. Your briefcase, sir.”

He turned to see his housekeeper, one hand over her mouth, choking back her laughter, the other extended with his briefcase. He snatched it out of her hand. Let them snicker. He was an Englishman.

Once inside the car, he breathed in deeply, closed his eyes, and leaned back against the plush, dark brown leather seat. He would set things right. He would see about the choosing Carlos Codrington had done. It would be his word against the word of an Englishman. In Chacachacare he would settle the score for every Englishman whose daughter and sister had become prey these days of the colored man.