Читать книгу National Geographic Kids Chapters: Dog Finds Lost Dolphins: And More True Stories of Amazing Animal Heroes - Elizabeth Carney - Страница 6

ОглавлениеChapter 1 CALL FOR HELP

When Chris Blankenship got an emergency call to report to the beach, he expected it to be busy. And it was!

About 80 dolphins were wriggling and squeaking in the shallow water. A small army of people worked quickly to help them. Team leaders barked orders. Volunteers put on wet suits for their turn in the water. News reporters were there too. They were looking for a big story.

Chris is a dolphin expert. He has seen dolphins and whales stuck on shore before. This time was different. Usually one or two dolphins get stuck in shallow water. Sometimes they get stuck in the twisty roots of mangrove trees. But 80 dolphins! Chris thought. With so many, how do we know that we’ve found them all?

Every time a dolphin or whale gets stranded, it is a race against time. The sooner the dolphins are found, the easier it can be to save them. Chris ran his hands over a dolphin’s smooth, rubbery skin. He thought how odd it was that such a good swimmer needed help.

Dolphins are perfect for the underwater world. With their strong bodies and sleek fins, they can swim seven times faster than humans. They can hold their breath for more than 15 minutes and dive 2,000 feet (610 m) underwater.

Dolphins are also very smart. They hunt in groups. They make up games to play. They even name themselves using whistling sounds. Many researchers spend their lives learning how dolphins communicate. In a dolphin’s world, every click, whistle, and gesture has a meaning.

Yet sometimes dolphins end up in trouble. They can get stuck on a beach. It’s a dangerous situation for them. By the time they are found, most stranded dolphins are sick or have died already.

Why would such smart animals swim so close to a beach?

We don’t really know. Maybe some stranded dolphins have been sick. Maybe pollution in the water confused them. Maybe they got lost during a storm at sea.

In order to find the answer, scientists study stranded dolphins as they try to help them. They look for clues that will help them keep dolphins safe.

Chris and the animal doctors got to work on the stranded dolphins. The first step: Make sure the dolphin can breathe. Dolphins are mammals, like humans. They have lungs and need to breathe air. They take in air through a blowhole on their back, behind their head.

The stranded dolphins were very tired. They couldn’t stay up on their bellies or swim on their own. People took turns holding the animals up so they could breathe. They rested the dolphins on their knees to keep their blowholes above water.

The volunteers also kept the dolphins’ skin moist by splashing water on their bodies. A dolphin’s exposed skin can dry out quickly in the hot Florida sun.

A team examined each dolphin. They had to find out which dolphins were healthy enough to survive in the wild. The healthiest dolphins were helped back to deeper water right away. Sick dolphins were taken to a special hospital. There they were given medicine and food.

Dolphins and Whales

All dolphins and whales are in the same family—a group of animals called cetaceans (SE-TAY-SHUNS). There are more than 80 different types of cetaceans. The common name for the whole cetacean group is “whales.”

Whales are divided into two groups:

(photo credit 1.3)

(photo credit 1.4)

Dolphins have teeth, so they are part of the toothed whale group.

| Baleen Whales | Toothed Whales | |

| How They Eat | Baleen (BAY-LEEN) whales have comb-like filters in their mouths. They suck in a ton of water and then strain it through the filters. | Toothed whales have a mouth full of shovel-like teeth so they can chew their prey. |

| What They Eat | Baleen whales eat tiny creatures called krill and plankton that get trapped in their mouths when all of the water filters out. | Toothed whales eat fish, seals, and squid, and some of the bigger whales might eat another whale. |

| Who They Are | humpback whales, blue whales, and bowhead whales | dolphins, killer whales, pilot whales |

Chris popped a fish stuffed with medicine in a dolphin’s mouth.

This one is in rough shape, but it seems like a fighter, he thought. Suddenly, a shout got Chris’s attention.

“Chris!” yelled a volunteer. “Quick! Come over here!”

Chris ran down the beach to a spot full of mangrove trees. A small group of dolphins were stuck in the trees’ thick roots. They must have been separated from the main group. Now it was too late. They were too sick to save.

Chris sighed. I wish we had some way of locating dolphins. Then we could get to them sooner.

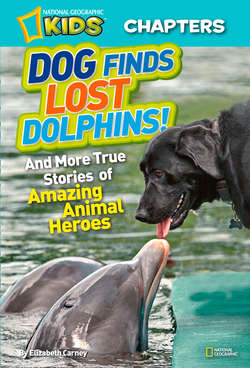

After that day, Chris kept thinking about what he had seen. He wondered if there was a better way to find lost dolphins. Then Chris started reading about some dogs that worked nearby. They were trained to search for people who get lost on or near the water. The dogs worked along beaches or from boats in the water. They sniffed the air for the missing person’s smell. They could even smell objects that were slightly underwater.

Chris wondered: If dogs can find humans in the water, can they find dolphins too?

Chris called Beth Smart, the head of the Dolphin and Marine Medical Research Foundation. Beth listened carefully. She liked the idea. Sure, no one had ever used a dog to find beached dolphins or whales. But that didn’t mean it was impossible.

Beth agreed to work with Chris on the project. “Let’s look for a dog!” she said.

One of Cloud’s trainers, Beth Smart, helps sick dolphins recover so they can return to life in the wild. (photo credit 1.5)