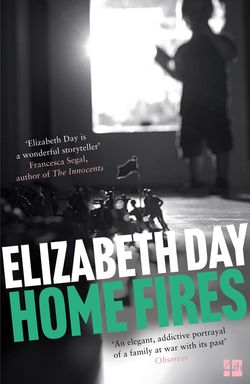

Читать книгу Home Fires - Elizabeth Day, Elizabeth Day - Страница 14

ОглавлениеCaroline

For Caroline, it had all started with a knock on the door.

Ta-tat.

A quaver, then a crotchet, thumped out against the wood.

She thinks now how odd it was that they knocked when there was a perfectly good doorbell, a square box nailed to the wall with a circle-white buzzer so that every time she passed it she thought of an unfinished domino tile. Andrew had installed it several years previously, disproportionately proud of his prowess with the Black & Decker drill she had given him for Christmas. At first, he put it too high up on the doorframe so that no person of average height would be able to reach it. Then he moved it down several inches, but the wood remained dotted with holes where the doorbell had once been.

So the point was: they must have seen the doorbell and chosen to ignore it. Perhaps, she thinks, it was protocol, an anachronistic gesture of respect from a time before the installation of domestic electronics.

Whatever the reason, it was a knock that signalled Caroline’s life was about to change. The knock seemed to echo more loudly than a buzzer, its staccato force reverberating clean and clear against the hallway tiles. It bounced off the buttermilk-painted walls, pinging its way like a pinball up to the top of the stairs where she was sitting cross-legged on the carpet in her jeans, folding freshly washed pillowcases to stack on a shelf in the airing cupboard.

She called to Andrew to answer. It was a Saturday and they had been out for the afternoon, shopping for things they believed they needed but probably could have done perfectly well without: cushions for the conservatory chairs, a new fig and bergamot scented candle for the living room, a long-handled spoon for jars of marmalade to replace one that had mysteriously disappeared. On the way back to the house, they had stopped for tea at the vegetarian café and shared a slice of carrot cake, the vanilla cream icing melting sweetly in their mouths.

There was no answer from Andrew and Caroline remembers being irritated by that. She remembers flinging down the pillowcase she had been folding and making her way hurriedly downstairs, cursing her husband’s absent-mindedness under her breath.

It seems so trivial now to have got upset over such a tiny inconvenience – magical, almost, to think that her life could have been so content back then that she had to invent reasons to be upset simply to give her day a bit of texture.

There was another knock before she got to the bottom of the stairs: three beats in quick succession.

Was it then that she began to sense that things were not as they should be? Was it then that she felt the first thump of blood to her head? She isn’t sure. There is a temptation, in retrospect, to claim some psychic maternal intuition that all was not right. But she doesn’t think she suspected anything. It had been a very normal Saturday up until that point. She does remember walking briskly across the hallway so that she wouldn’t keep whoever it was waiting.

She was still, at that time, mindful of the necessary social politesse.

She walked down the hallway and looked through the glass-panelled front door to see a warped beige-blue darkness, an indistinct, lumpy shape that gradually shifted apart into two inky shadows. One of the shapes appeared to have yellow stripes on one shoulder but when it moved, the yellow dispersed, swirling into flakes of confetti with each dent of the glass. She squinted, unsure of what she was seeing and yet aware that it was somehow an echo of a thing she recognised.

Something about the way they were standing, erect, unbowed, certain, made the pieces fall into place. In her mind, the jumbled sparkle of a hundred kaleidoscope fragments slid into sudden formation.

Two men.

Uniforms.

A knock on the door.

This is what happens when soldiers die.

She felt a hole in the base of her stomach, as though something had unclenched within her and yet she kept moving towards the door. She turned the handle and opened it several inches but then she stopped, not trusting herself any further. Her eyes were shut, as if she were a child who could make something disappear by not seeing it.

‘Is this 25 Lytton Terrace?’ said the first man. ‘Are you Mrs Weston?’ He was dressed in charcoal grey and wore a gold signet ring on his little finger polished to an iridescent brightness. She didn’t notice his colleague until much later.

Time slowed. The seconds dripped like treacle from a spoon.

‘Would we be able to come inside?’ the first man asked. And she knew, then. She knew.

She bent over before he could say any more, clutching at her waist, head dropping down so that she did not have to look at them. For a few seconds, she could make no noise. It felt as though the next breath would not come but remain, halted, just beyond her reach. She moaned. She said ‘No,’ and her voice when she heard it sounded far away: a whisper on the opposite side of an echoing cave.

She slammed the door shut. She leaned against it with her whole weight, pushing the glass with her hands, fingers splayed against the light. She pushed so hard that her flesh turned white and numb. And all the time she was saying no, no, no, feeling the lurch of desperate nausea in the pit of her stomach, the sweat breaking out underneath her arms and trickling down her spine. She was shaking her head, refuting the thought that this could possibly be real. It was not true. It couldn’t be.

The two men knocked on the door again, saying her name, trying to be kind, but she couldn’t let them in. She would not let them into the house. She would not listen to what they had to say. She thought to herself that if she could stop them from speaking, if she could keep the door shut, if she could prevent them crossing the threshold, then everything would stay the same. She would prise open a gap in time, a velvety corner she could squeeze into where she would be safe, cocooned.

She heard footsteps running up behind her and for a moment she thought that the men had somehow got inside the house and were coming to get her, but then she remembered Andrew. Her husband.

She remembered with a rush that he existed, that he was with her, that she was not alone, that there was a rational shape to things, and then she felt his hands around her wrists, his warm, reassuring palms firmly gripping her throbbing veins. He was murmuring, saying something to her that made no sense, but his voice was familiar and soothing and the tendons in her hands relaxed as he prised them off the glass and held them tightly in his. She looked at his mouth and it was moving and he was making a sound but it took several seconds until Caroline could understand anything.

‘We have to let them in,’ he was saying. ‘We have to let them in.’ And his face was colourless and scared and she was shaking her head, but he simply kept repeating the same phrase over and over and she was lulled by the weird rhythm of his voice and then she felt exhaustion come over her and she slumped against him while he opened the door and let the two men in dark suits across the threshold.

And that is how she learned that her darling son was dead.

Later, the two men tried to tell her how Max had died but all Caroline could hear was a vague blur of voices. She had the overwhelming sensation of being too cold and then she went limp in Andrew’s arms, as if she no longer possessed enough energy to expend on even the most basic of tasks. He half-carried her to an armchair in the sitting room, upholstered in a flowered pale-green fabric and she turned her head and pressed her face into the back of it so that she would not have to look at anyone.

She breathed in the armchair’s comforting scent of hair and familiar sweat and felt the roughness of the material against her skin. She stared at a sun-faded lily stitched into the fabric, noticing the curl of the petals and the worn-away threads of the stalk. She did not cry but according to Andrew, she was whimpering – that was his word, ‘whimpering’ – like a broken-down dog limping to the side of a road.

Andrew managed to ask the relevant questions, to elicit the desired information, his voice flat and devoid of emotion, his hands placed carefully over the curve of each knee-bone. The two men said that Max had been on foot patrol in Upper Nile State, scanning the African countryside for pockets of resistance and ensuring the safety of the local villagers, when he stepped on a landmine. For some reason, they didn’t call it a landmine. They referred to it as an Improvised Explosive Device, or IED. An acronym. It seemed wrong, somehow, to reduce his death to three slight letters.

The landmine had exploded directly underneath Max’s feet. He was thrown backwards several metres, landing on his back and snapping his vertebrae. A two-inch piece of shrapnel sliced his chest in half. It lodged itself so close to his heart that the army doctor who got to him some time later could not risk extracting the metallic fragment in case it increased the bleeding. The doctor did what he could to staunch the flow of blood, pressing down with his own hands when they had run out of balled-up T-shirts and improvised bandages.

There would, she imagines, have been a few seconds when it could have gone either way: that fragmented moment that lies between the everyday and the nightmare. And then, in a faraway country, lying in a pool of his own blood, he stopped breathing. And that was it for Lance Corporal Max Weston, aged 21. That was it.

When the men had finished speaking, Andrew offered them a cup of tea. They said no, and she was relieved by that; relieved that they did not have to pretend or act normally.

Caroline had questions. So many questions.

What was Max’s last thought?

Do you have last thoughts when you are dying?

Would his life have flashed through his mind as one is told it does, or would there not have been enough time?

What would his face have looked like?

Was his skull still intact, the smooth dip into the nape of his neck that she loved so much?

Was he always meant to die at 21? Was the shadow of his death hanging over them all during those times they had together? Had they simply been too arrogant or too innocent not to pay attention to it?

Did he think of his mother at all?

Did he know how much she would miss him?

Did he know that he was her life, her everything?

And: without him, how could she go on?

In the days that followed, Caroline would spend hours sitting in the kitchen, a mug of cooling coffee cradled in her hand, thinking back to the time when Max was a child, searching for any clues she might have missed about the path his life took.

But the irony of it was that Max had never played with soldiers when he was little. Andrew had once given him a much-cherished set of tin figurines, inherited from his own father, in the hope that Max would carry on the Weston family tradition of reconstructing interminable historic battles on the bedroom carpet. When Max opened the musty cardboard box and inspected the soldiers’ minute Napoleonic uniforms greying with age, their bayonets blunted by the repeated pressure of other children’s excitable fingers, he was distinctly unimpressed. He was nine years old – the perfect age, one would have thought, for playing with action men.

‘You see, this chap here,’ Andrew said, lifting up a portly-looking gentleman on horseback, ‘is in charge of the cavalry.’ And he passed the toy to Max, who looked pensively at his father before taking it wordlessly in his hand.

‘Why is he on a horse?’

‘That’s how soldiers used to fight. In the old days. It meant they could move faster and cover more ground.’

Andrew looked up at Caroline and caught her eye and she could see he was delighted by Max’s tentative curiosity. He up-ended the box and the soldiers tumbled out in a metallic heap. Max looked on warily, the cavalryman still clasped in his hand. He was an extremely thoughtful child, in the original sense of the word: he would examine everything with great care before deciding what to do about it. Unlike most boys of his age, he was not given to spontaneous outbursts of random energy or unexplained exuberance. Rather, he would step back and evaluate what was going on and then, if it was something that interested him, he would join in with total commitment.

He was selective about the people and hobbies he chose to pursue but Max’s loyalty, once won, was never lost. From a very young age, he pursued his enthusiasms with utter dedication. After a school project on the history of flight, he spent hours making model aircrafts and would put each new design through a rigorous set of time trials in the hallway, recording the results neatly in a spiral-bound notebook. When he discovered a talent for tennis, he practised religiously, hitting a ball against the back wall of the garage until the daylight faded. He met his best friend Adam on the first day of primary school and although they did not immediately take to each other, they became close through a shared love of Top Trumps and were then inseparable, all the way to the end.

But in spite of Andrew’s early optimism, he never could get Max to play with those tin soldiers. For weeks, they remained in a haphazard heap on the floor – the cavalryman standing disconsolately on his own by the skirting board looking on with despair at the unregimented jumble of his men – until Caroline cleared the toy army away, putting them all back in the box which stayed, untouched, underneath the bed in Max’s room for years. In the days after his death, she took to going up to his room and sliding the box out. She liked to find the cavalryman and to hold him in her hand and to think that her son had also held him like this. It made her feel that she could touch Max again in some way, as if a particle of his skin might still have been lingering on the silvery-cool surface and they could make contact, even through the tangled awfulness of all that had happened. She sat for hours like that, feeling the time ebb gently away.

Perhaps Max was a gentle child partly because he did not have to compete for their attentions with other siblings. It had taken them years to conceive and then, just at the point where it had seemed to be hopeless, Max had made his presence known. The first time Caroline heard him cry after he was born, she instantly recognised it as the sound of her child. You could have put Max in an auditorium full of wailing babies and she would have known. Andrew made fun of her for that, but he couldn’t have understood. He wasn’t there at the birth – men in those days weren’t – and she felt afterwards that he had missed out. Deep down, there was still a part of her that felt Andrew was never as close to their son as she was. And now, as she sat in the kitchen chair, the lingering acridity of coffee in her mouth, she genuinely didn’t believe his grief could be as profound as her own.

The military was the last career either of them had imagined for Max. He grew into a popular, self-assured teenager, the kind of boy that seems to radiate light. He was good at everything: academically gifted, a brilliant sportsman and yet he retained an artistic temperament, a kindness around the edges that set him apart from his contemporaries. His friends all said so at the funeral.

He was made head boy even though he attended the local boarding school as a day-pupil and it was practically unheard of for a non-boarder to be asked. They were talking about Oxbridge, wondering whether to put him up for a scholarship, and then, without warning, Max announced over dinner one evening that he wasn’t going to university.

‘What do you mean you’re not going to university?’ said Andrew, his knife and fork hanging in mid-air.

Max laughed. He had this infuriating habit of defusing tension with laughter – it always worked because it made it quite impossible to be angry with him.

‘I mean just that, Dad. I’m not going. I don’t think it’s right for me.’

Caroline looked at her son and saw that, despite the twitch of a smile, he was totally serious. She saw, all at once, that he would not be dissuaded. She had always imagined Max would be a barrister or an academic, someone who wore his success lightly and yet who was all the more impressive for it; someone who was impassioned by what he did and yet not defined by it. She could see herself talking about him to her friends in that murmuring, boastful way that proud mothers have, dropping nonchalant mentions of his latest achievement into conversation. She had wanted everything for her son, for him to achieve all the things she was never able to.

But his announcement shattered that illusion in a matter of seconds. Caroline forced herself to adopt a lightness of tone.

‘Well, darling, what on earth do you intend to do? Sweep the streets?’

Max grinned and patted her hand. ‘Fear not, mother dear. I don’t intend to end up destitute or homeless.’

‘And before you get any ideas, let me tell you I certainly won’t be doing your stinky washing any more,’ she said, punching him lightly on the arm. Max squinted with pretend pain. ‘Ow!’ He grinned. ‘Mum, you don’t know your own strength.’

She laughed. Then she saw Andrew out of the corner of her eye, his face set in rigid lines of worry and disapproval. She wanted to reach out to him, to rest her hand on his arm and tell him it was going to be all right. But she felt torn. She did not want Max to feel she was taking sides. So she waited.

‘What are your plans, Max?’ Andrew asked after a while.

‘I thought I’d join the army.’

There was a stunned silence, broken only by the sound of Max chewing on a piece of steak.

Andrew put down his knife and fork.

‘The army?’

Max nodded. He pushed his unfinished dinner to one side, the plate still heaped high with potatoes and limp green beans. The butter from the fried mushrooms was congealing at the edges, like wax.

‘Where on earth did you get that idea from?’ asked Andrew. Caroline looked at her son and noticed his eyes getting darker. She didn’t want there to be a scene.

‘We never realised you were interested in the military,’ Caroline said, trying to be conciliatory. It seemed to work. Max’s shoulders relaxed. He was still wearing his tatty brown denim jacket for some reason. Perhaps he had been on his way out somewhere – he had an incredibly active social life – but the brown bagginess of the material combined with his uncontrollable mop of hair gave him the air of an enthusiastic teddy bear. She had to stop herself from reaching out and pushing the floppy strands of blond hair away from his forehead.

‘It’s something I’ve been thinking about for a while,’ he said. ‘I know it’s not what you wanted or expected for me and I’m sorry for that, but you’ve always taught me that it’s important to do what you love –’

‘Within reason,’ Andrew interjected.

‘OK, well, I know I’m good at schoolwork and exams –’

‘You’re more than “good”, Max. You’re academically gifted. Your teachers are talking about Oxbridge.’

‘Dad, please let me finish. I might be good at school but I don’t love it.’

‘What do you love?’ Caroline asked.

‘I love being part of a team. I love sports and being captain of rugby and people respond to me, Mum, they do. I’m a good leader. I like that about myself. But most of all I like the thought of doing something that counts. That really, truly counts for something.’

‘Oh come on, Max,’ said Andrew. ‘Wanting to make a difference is not the same thing as offering yourself up to get killed.’

‘Isn’t it?’ Max looked at them both steadily, still slouched on the table, his chin propped on his hand as if this were the most casual discussion in the world.

Neither Caroline nor Andrew knew what to say to that.

‘How can you truly change anything unless you’re willing to die for it?’ Max asked and it sounded like something he had heard, a phrase to be played with like a picked-up pebble.

‘Well, that’s very philosophical of you, Max, but I don’t think you know what you’re talking about . . .’

‘Have you thought of going to university first and then making a decision?’ Caroline suggested. ‘At least then you can leave your options open.’

But she could tell, even as she was mouthing the words, that there was nothing either of them could do to change his mind. There was something about the way Max was talking, something about the utter certitude with which he met his father’s eye, that made Caroline realise he thought he had found his vocation. She had never heard him so determined.

They found out later that a serving officer had been to speak at the school, invited by the politically correct careers department who were no doubt keen to introduce the pupils to a representative cross-section of society. In the same month, the school also hosted talks by a high court judge and the home affairs editor of a national newspaper. For whatever reason, Max was not enthused by what these two had to say. It was the army officer who inspired him and, as with the model airplanes and tennis practice and as with Adam, his best friend, Max had given himself over entirely to the idea of becoming a soldier and would remain loyal to it until he died.

To Caroline’s surprise, Elsa gave her unequivocal backing to Max’s decision. Part of her wondered whether her mother-in-law was doing it deliberately, to show her up for her failings, to show her that she had never deserved the privilege of being Max’s mother or Andrew’s wife.

Elsa’s phone call came on a weekday morning, when she must have known Andrew would be at work. Caroline immediately assumed her brightest telephone manner, obscurely flattered by the fact Elsa had chosen to speak to her and her alone. Normally, she would only have gone through the motions with Caroline – how are you, how’s Max, how’s the garden, what are you having for supper, that kind of thing – until, after a reasonable interlude, she could ask to speak to Andrew, as if Caroline were simply some sort of conversational gatekeeper that had to be got through. But on this day, it was different.

‘Caroline, it’s Elsa,’ she said, even though the kitchen telephone had already flashed up with her number.

‘Hello, Elsa. How are –’

‘You simply must allow Max to join the army,’ she said, cutting in. ‘He’s told me all about it.’

‘Max has told you about it?’ Caroline asked, incredulous. When had he done that?

‘Yes, he called me last night and he says you and Andrew are opposed to it.’

Caroline felt her shoulders tense. ‘We’re not opposed,’ and a note of defensiveness crept in to her voice.

Elsa backtracked. ‘No, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to say that. What he said was that you were trying to be supportive but he could tell your heart wasn’t in it.’

‘Well, Elsa, I don’t think that’s so surprising.’

Her mouth was dry. She disliked the idea of Elsa currying favour with Max, of exploiting a momentary lapse in her judgement. She disliked the thought of the two of them being close, forming an alliance that excluded her.

‘No, of course not,’ Elsa said. ‘I’m sure it must be very difficult to think of your son in that kind of danger but Caroline, you must realise . . .’ And the next words were so surprising, Caroline was not at first sure she had heard them correctly. ‘You must realise that young men need to fight. They need to get it out of their system.’

Caroline was so taken aback that she did not think to question then why Elsa said it. It seemed such a curious statement of fact from an elderly lady whose only son was an accountant. What could she possibly know about a young man’s need to fight?

Elsa carried on talking. ‘I’m worried that if Max doesn’t do this, he’ll end up feeling he’s never proved himself. He’ll take it out on someone or something else. He’ll make stupid decisions. He won’t want to be thought of as a coward.’

‘But . . .’

‘There, I’ve said enough,’ Elsa said, resuming her customary briskness. ‘I’m sure you think this is none of my business, Caroline, but for reasons I can’t go into, I feel very strongly about this.’ And then she put the phone down.

Caroline did not tell Andrew about the conversation but she soon came to realise that unless she showed Max her wholehearted support, she would risk pushing him away. He would seek out other friends, people who were more sympathetic to his ambitions – people like Elsa. The thought of this scared her. She did not want to lose him. So she gave Max her blessing. In time, Andrew had followed.

There was no stopping Max after that. He signed up to 1 Rifles, part of the 12 Mechanised Brigade based in Bulford and when his parents went to Wiltshire for his passing-out parade after thirty-eight weeks’ basic training, he stood proud and bold in front of them, his hair shaved short, his shoulders broad and bulked-out underneath the uniform and Caroline wore a bright red hat and Andrew wore a dark grey suit and they clapped along with all the other parents and smiled and flashed their digital cameras and shook their heads in shared disbelief at how grown-up their children seemed. Max, surrounded by friends, his tired eyes gleaming, was in his element.

She has a photograph from that day of the two of them, taken by Andrew. In it, Max is laughing, his handsome head tilted backwards. He has his arm around her and Caroline remembers that the stiffness of his uniform made his movements unnaturally heavy. She has her hand on his chest, lightly resting just below his heart and her lipsticked mouth is stretched into a smile that manages to be both joyful and anxious. But Max . . . well, Max looks wonderful.

Sometimes, now, Caroline will see other bereaved families on the evening news who have been trotted out for the television cameras by the Ministry of Defence and they look like half-people, their ghostly outlines blurred from the ghastliness of their grief. They look slumped and shattered, shuffling forwards as if their spines are sagging, grey-faced and shaken and not quite comprehending the all-encompassing reality of what they have just been told. Often, these families will have a statement that they wish to read out. Most of the time, this statement will contain a line about how, in the midst of this terrible tragedy that has engulfed them, they take comfort from the knowledge that Paddy or Niall or Ian or Geoff or Ben died ‘doing what they loved’.

Perhaps, Caroline thinks, it should give her succour now to think that Max died doing something he loved so much. But it doesn’t. It makes her angry that he chose to put himself in danger. It makes her angry that no matter how much she loved him, it wasn’t enough, that he needed something else. It makes her angry that he’s dead. And, above anything else, it makes her angry that she was too gutless to stop him.

Because, after all, what is the point of a mother if she cannot protect her only child?

His body – what there was of it – was flown back on a military plane. They were driven up to RAF Lyneham in a plush black Mercedes provided by the army and although they held hands in the back of the car, Caroline felt completely separate from her husband. She rested her head against the window, watching the motorway service stations skidding by, the spindly trees caked in exhaust fumes, the dull, overcast sky that seemed to stretch for ever in a uniform pale brushstroke, and she could feel nothing. She was numb, empty, hollow.

‘You OK?’ asked Andrew, turning to look at her with dark-circled eyes.

She didn’t answer. She tried to nod her head but it felt like a lie.

Once they got there, they lined up with the other bereaved parents in a surreal sort of welcoming committee. One of the mothers, a thin streak of a woman with badly cut hair, smiled at Caroline and then started crying so that for a moment it looked as though her face had been split into two halves in a game of consequences.

Three coffins covered in Union flags were carried out of the plane’s hull in slow succession, each one held aloft on the shoulders of six uniformed men who walked with respectful sombreness across the tarmac. It was very windy and Caroline’s hair kept slapping across her face.

The woman who had smiled at her was now crying uncontrollably, segments of a balled-up paper tissue in both hands. Her husband had his arm around the woman but kept looking straight ahead, his gaze masked, two thick wrinkle-lines etched from the corners of his mouth down either side of his chin.

Andrew’s arms were crossed. His head was angled to one side so that she could only just make out the pinkish trace of a shaving cut on one side of his cheek. A tear, translucent and slippery as a slug’s trail, was falling down his face. Caroline was surprised to see it there and she realised that, until now, she had never once seen Andrew crying.

The sight of him – vulnerable but trying not to be for her sake – moved her. She held out her gloved hand and he took it, gratefully. But then, with her hand in his, she started to feel trapped, as if she were betraying something, as if to be thinking of anyone else but Max in this moment was a form of disloyalty. For so long, she had relied on Andrew to be her rock. But now, she did not want him near her.

For her part, Caroline had no tears. She found that her grief was so vast it blanked everything else out. It was as though she were in the middle of a storm, perfectly calm at its epicentre but looking outwards at the whirling mayhem, the engulfing waves and thunder-split skies, the spiralling madness of normality ripped apart at the seams.

As she watched the soldiers carrying the coffins across the tarmac, she found herself remembering – of all things – the time she took Max to have his warts treated with liquid nitrogen at the hospital. He was 10 and his middle finger had bubbled up, the skin becoming hardened and nodular. None of the over-the-counter wart treatments worked, so they had driven one morning to the hospital, Max sitting in the front passenger seat, holding his finger up to the light to examine it better.

‘Why can’t I keep my wart?’ he said in his plaintive, inquiring way.

‘Because it’s contagious.’

There was an effortful silence as Max considered this.

‘What does contagious mean?’

‘It means . . .’ she pondered how best to describe it. ‘It means other people can catch them.’

‘Like a ball?’

‘No, like the flu.’

That seemed to satisfy him and he was very brave with the doctor, pressing his hand down on to the table as he was told, trembling only the tiniest bit when the liquid nitrogen was applied with the tip of a cotton bud. But Caroline could tell it hurt because he blinked quickly three times which was exactly what he had done two summers previously after fracturing his elbow falling off his new bicycle.

As they walked to the hospital car park, she asked him whether it had hurt.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘But I don’t know how it felt.’

She looked at him, surprised. ‘What do you mean?’

‘It felt really hot but it also felt really cold and I couldn’t work out which it was. It hurt too much to know.’

Eleven years later, watching him come back to her in a box and a body-bag, that was how it was for Caroline: too painful to know what she was feeling.

The casualty visiting officer, a whey-faced woman called Sandy, told them that the army would pay for Max’s funeral. She told them this as if it were a great favour.

‘So you and Mr Weston won’t have to worry about any of that,’ she said, with a sympathetic expression that looked as if it had been ordered from a catalogue of necessary human emotions. Caroline was in the middle of making her a mug of tea. Instead of answering, she asked: ‘Do you take sugar?’

‘Yes, two please.’

Two sugars, thought Caroline, how common. She had stopped taking sugar years ago after Elsa had commented, devastatingly, on her ‘terribly sweet tooth’.

Still, Caroline thought to herself as she stirred the loose leaves into the pot, there was no accounting for taste.

She brought Sandy’s tea to the table. They were sitting in the kitchen, in the extension they’d had built after Max left for his training in Bulford. It had sliding windows that opened on to the garden and the light that day was streaming through, showing up the dusty streaks and cobwebs that Caroline hadn’t got around to cleaning from the glass. You couldn’t see the Malvern Hills from the kitchen but you could feel their presence, crouching like cats across the horizon.

Andrew, sitting across from Caroline with a file of papers in front of him, nodded at the officer absent-mindedly and made a note of something on the uppermost sheet of typed A4. Sandy was looking at her expectantly, clearly worried that Caroline wasn’t taking anything in. ‘The army will pay for the funeral, for everything,’ she emphasised, enunciating each word with extra care.

Something about the way she spoke, in that patronising, slow voice used by teachers when a child is failing to grasp an elementary fact, made Caroline snap.

‘Am I meant to be grateful for that?’ she said. Andrew looked at her cautiously.

‘The army will pay for his funeral? Well, that’s terribly good of you,’ Caroline continued, her voice squeezed tight. ‘How kind. Still, I suppose it’s the least you can do given that you were the ones who killed him.’

Sandy coughed uneasily. Andrew reached across the table and put his hand over Caroline’s. She snatched it away.

‘They are doing the best they can, Caroline,’ he said in a level voice.

She stared at him. She could not understand why he insisted on being so reasonable.

‘They killed our son.’

He shook his head. ‘No, darling, no they didn’t.’

‘They sent him there.’ Caroline could hear her words getting higher and more frantic. He had never listened to her, ever. He had never believed her opinions were worth having. She felt that she had to shout, to be louder than he was, just to make him hear what she was saying. ‘They ordered him out on patrol so that he could step on a fucking landmine!’

The swear word sliced through the room. Sandy put her mug of tea down carefully on a coaster.

‘Mrs Weston, I didn’t mean to . . .’

‘Don’t . . .’ she said. And then, more quietly, almost apologetic: ‘I’m sorry, but you have no idea.’

She stood up with such a jolt that the chair toppled over and clattered against the floor.

‘Caroline,’ Andrew said. ‘Calm down.’

It was those words that tipped her over the edge. Arms crossed, she dug her fingernails into the fleshy part of her bicep, to stop herself from letting go, to remind herself that she must act appropriately. But inside, she imagined lifting up her mug and hurling it at the wall. It would shatter on impact and spray the room with porcelain shards. She imagined a brown trickle of tea streaming down the paintwork and gathering in a pool at the skirting board.