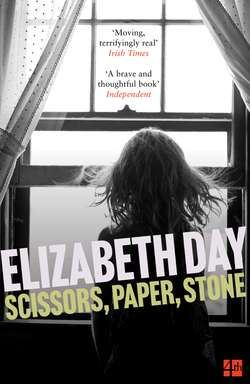

Читать книгу Scissors, Paper, Stone - Elizabeth Day, Elizabeth Day - Страница 15

ОглавлениеAnne; Charlotte

They settled into an unspoken routine at the hospital so that the days slid into weeks and the weeks became something approaching permanence. They discovered that it was easy – easier than it should have been – for life to swallow up the extraordinary and weave it into normality. Shock became a sort of weariness. Terror became a numb suspension of time. The anxiety that had gripped them in the immediate aftermath of his accident transmuted into a dull, nagging sensation of having to do something. Hospital visits were no longer something to be feared, but rather an event to be got through, ticked off as part of the day’s routine.

Anne, who had never held down a permanent job, found that it was almost a relief to have something with which to fill her time other than the endless caffè lattes with Janet or the daytime soaps she pretended not to watch. There was a release, too, in not having to think of what to cook for supper. When Charles had been awake, the constant grind of coming up with a new combination of meat and vegetables had loomed over every single day, assuming grotesquely inflated proportions so that almost as soon as she woke up she would start tormenting herself with visions of lamb chops and green beans. Now, with Charles in hospital, she picked up whatever she felt like from a Tesco Express on the way home. She delighted in the oddness of her dietary whims. Once, she had eaten a packet of marinated tofu and two Braeburn apples and felt utterly content.

She visited Charles every day, so that the receptionists started to recognise her and wave her through without asking for the customary ID. It was a nice, private hospital with a river view over the Thames and room service menus offering glasses of Chardonnay (unoaked). The overall impression was one of an efficient business hotel, on the edge of a motorway between cities.

There was a television suspended on the wall in Charles’s room that had all sorts of satellite channels that Anne did not have at home. Since he had been ill, she had become a connoisseur of trash. There was an American programme she particularly liked that was a reality search for a new fashion model. It seemed to be endlessly repeated and Anne always liked to watch the ‘makeover’ episode where seemingly plain-faced girls with dull eyes were transformed, by dint of hair dye and teeth whitening, into glamorous visions of fabricated beauty.

She got an illicit thrill from the certain knowledge that Charles would have hated the programme, would have sat scowling in the room, making his disapprobation painfully obvious with every heavily exhaled breath. The only television he watched was the News at Ten or Panorama, although he’d gone off the latter when the BBC cut it down to half an hour. Anything else would prompt him to launch into a critical analysis of why Anne felt she had to rot her brain by watching ‘rubbish’. She had become used to recording her favourite programmes and looking at them late at night, after he had gone to bed, with the volume turned so low she had to strain to hear what the characters were saying.

Anne liked the hospital for its sense of quiet order and the wordless comfort offered by the nurses’ sympathetic glances. Part of her felt she did not deserve their arm pats and smiles. Over the years, she had successfully convinced herself that Charles had become a fact rather than a person, something to be borne, to be lived with and endured rather than loved and looked after. It wasn’t that she was callous. It was rather that she had had all her tenderness battered out of her. She found a sense of peace by Charles’s bedside that she had not known for years. And, of course, it brought her physically closer to Charlotte.