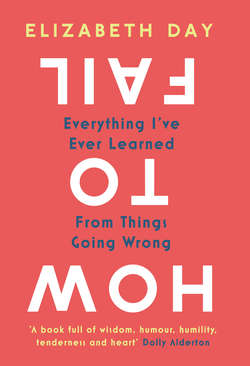

Читать книгу How to Fail: Everything I’ve Ever Learned From Things Going Wrong - Elizabeth Day, Elizabeth Day - Страница 10

How to Fail at Your Twenties

ОглавлениеI got into Cambridge University. I did well at my exams there too, having fallen into the habit of doing everything I could to achieve the best grades. I enjoyed my time at Cambridge because, true nerd that I am, I loved my subject and geeked out reading Plato and studying war memorials and writing essays with linking words such as ‘nevertheless’ which I thought made me sound intelligent (I was wrong).

I also met my best friend, Emma. She was standing in the corner of the college bar one evening in freshers’ week. A half-Swedish blonde-haired sexpot, she wore a slogan T-shirt with ‘One for the rogue’ emblazoned across the front and was holding a pint in one hand. Inevitably, she was surrounded by a gaggle of slavering men who could barely keep their tongues from flopping out of their teenage mouths.

Whoever that is, I thought as I walked in and ordered my old lady gin and tonic, we are so not going to get on. At first glance, Emma looked like one of the popular girls I had lived in fear of since the days of Siobhan. But then one of the men I knew vaguely from halls beckoned me over and introduced us, and Emma looked straight at me, ignored all the guys trying desperately to get her attention, and started quoting dialogue from the Austin Powers film. She turned out to be so incredibly funny and so disarmingly unaware of her own gorgeousness that, right then and there, I fell in platonic love.

Emma has the most darkly hilarious sense of humour I’ve ever encountered, and it’s so unexpected because she looks so sweet and pretty when you first meet her, and also because later in life, she became a psychotherapist and a very seriously successful person. The contradiction is part of her considerable charm. In our final year at university, we lived together in student rooms. We used to have friends over for ad-hoc dinners, although because we had no kitchen, we were severely limited in what we could offer in terms of food (most of the time it was guacamole, I seem to remember). Emma and I washed the dishes in the bathroom basin, and left them to dry on the window-sill, which meant that occasionally we’d be awoken by a dramatic crashing sound as soap-sudded plates slipped off the ledge and ricocheted into the alley below. I truly hope no passerby was ever injured, but I cannot guarantee it.

After graduating, I upgraded to a place with a kitchen and lived in a house-share in Clapham, along with approximately 98 per cent of nicely spoken, middle-class recent graduates hoping for a career in the media or management consultancy.

In my imagination, after the success of my university years, this was going to be a halcyon period of my young adulthood. I had been an inveterate fan of the 1990s TV drama This Life, which followed the lives and loves of twenty-something lawyers who sported cool hair and cracked jokes like pistachio shells. On This Life, everyone slept with each other and drank together and smoked in their house with the windows closed because there was no one to tell them not to.

I thought my twenties were going to be spent in similarly low-lit bedrooms, where I would burn a perfectly judged stick of soft jasmine incense and have a great piece of contemporary art casually slung on the wall. In the mornings, I would be hungover from the wild night before, but hungover in a messily attractive way, like a girl in a music video with tousled hair.

I would get up and make myself an espresso even though I didn’t really like espresso and I would sit at the communal kitchen table and laugh throatily at some clever comment made by one of my handsome male house-mates, who was probably in love with me but couldn’t admit it yet.

I would scrawl witty reminders of our weekly house dinners on Post-it notes that I would stick on the fridge, which would only ever contain bottles of champagne, vodka, gel eye masks and a tub of low-fat cottage cheese and then I would leave for work, wearing high heels and a silk blouse and a tailored skirt, and probably designer shades because I could afford them now that I’d paid off my student loan and, besides, it was going to be perpetually sunny in my twenties.

That, at least, was the plan.

The reality didn’t quite match up.

The house in Clapham was lovely, as were my house-mates (one girl and two boys, none of whom was in love with me, unforgivably) and the rent was absurdly low. My room was on the top floor and had a sloping ceiling and a window looking onto the back gardens of the next-door street. I felt like James Stewart in my favourite film, Rear Window. Except without a cast on my leg. And without witnessing a murder. Apart from that, though, totally the same.

In other ways, my twenties did not live up to the hype. I had envisaged an age of carefree light-spiritedness, in which I would finally be able to do what I wanted in both work and play. All the hard stuff – exams, finals, student foam parties – was over, I thought. Now I’d finally be able to forge my own path and spend my own money, free of the chafing restrictions of family, school or university.

But what actually happened was that I had a hard time balancing all the various aspects of my life and my identity, which (although I didn’t realise it at the time) was still very much in the process of forming. My twenties were a constant juggle between adult responsibility and youthful impulse and often I felt as though I was failing in both areas.

The house-share, for instance, should have been fun. And sometimes it was. But I spent too much time worrying about trying to be a grown-up. I had a long-term boyfriend, and he frequently stayed over and ate absurd amounts of food, so that soon I had to factor him into my grocery shopping. This being the heyday of Jamie Oliver, I decided I would be the kind of person who was good at cooking, so at weekends, I made roast lunches but would generally put far too much salt and oil on everything in the mistaken belief that made it somehow ‘Mediterranean’. In the spirit of improvisation, I once roasted a tray of broccoli florets. They emerged from the oven desiccated and sad-looking, and when we ate them, they tasted of charred grass and I realised there was a reason no one had done this before.

That was the thing about my twenties: it was meant to be a decade of experimentation, but sometimes the experiments taught you nothing other than that you shouldn’t have done it in the first place. Yet all around me, everyone else seemed to be having a wild time experimenting with drink, drugs and sexual partners, and I felt I should be doing the same. There was a pressure to conform to the tidal wave of non-conformity.

But the thing was, I had a full-time job to be getting on with.

I was lucky enough to have graduated with a job offer in place from the Evening Standard, where I had a spot on the Londoner’s Diary, a gossip column that liked to pretend it wasn’t really a gossip column by carrying acerbically hilarious items about politicians and Radio 4 presenters and big-name novelists rather than the TV celebrities they perceived to be more low-rent. A lot of my job involved going to parties and sidling up to famous people I’d never met before, then asking them an impertinent question designed to make an entertaining titbit for the next day’s paper.

‘Oh how fun,’ people would generally say when I told them. And I would reply that yes, yes it was and then I’d regale them with the time I met Stephen Fry at the Cannes Film Festival or the occasion on which I’d told Kate Winslet my house-mate kept rewinding the bits in her biopic of Iris Murdoch where she went swimming naked in the river (she looked taken aback, which is understandable given that the film is an emotionally draining tale of one of our finest modern writers’ descent into the ravages of Alzheimer’s. The naked swimming was very much an incidental thing).

But although I got to go to extraordinary parties and premieres and meet famous people, my job wasn’t actually that fun. For one thing, I’m a natural introvert and walking into glamorous parties on my own, not knowing anyone but feeling totally convinced everyone else knew each other, was pretty nerve-wracking. I’d have to psych myself up beforehand, and remind myself of my mother’s wise words that ‘no one is looking at you as much as you think they are’. I’d grab a glass of champagne as soon as I could so that I’d look like I was doing something, and then I’d skulk by the wall trying to seem as if I were expecting my date to turn up momentarily.

My friends also charitably assumed I was constantly being propositioned by famous people.

‘I bet it’s a total shag-fest,’ one of my house-mates said when I fell through the front door at 2 a.m. on a weeknight, having just been to the Lord of the Rings premiere where it was impossible to get to Orlando Bloom through the fire-breathing dwarves dressed like hobbits.

‘It really isn’t,’ I said but I think everyone believed I was being terribly discreet. In truth, I never slept with anyone I met through work and no one I’ve ever interviewed has tried to come on to me, except maybe once, many years later, when the flirtation was conducted over email. The famous actor in question was filming on Australia’s Gold Coast (good tax breaks, apparently) and would regale me with long anecdotes involving running along the beach and quoting T. S. Eliot to himself. Nothing ever came of it. You simply can’t date a man who tells you all about his exercise regime in excruciating detail and then quotes post-modern poetry in the same sentence.

Anyway, at parties, I’m one of those people whose resting face assumes an unwittingly haughty expression. During the Londoner’s Diary phase, this meant no one ever approached me.

Eventually, I’d spot someone who bore a passing resemblance to a man who might or might not have been the reality TV star who tried to survive for a year on a remote Scottish island or a woman who might or might not have been the It-girl daughter of a famous father who did something in construction, and I would take a deep breath and bowl over and ask them who they thought was going to be the next James Bond. This was my fail-safe question, because the British are incomprehensibly obsessed with who is going to be the next James Bond and whatever anyone said was deemed newsworthy.

Most of the time, celebrities were nice to me. Pierce Brosnan and his wife were absolutely lovely when I met them at a film awards ceremony and I have never forgotten it, even though the entirety of our exchange ran something like this:

Me: ‘So, Pierce, can I ask – who do you think will be the next James Bond?’

Pierce: ‘Oh, you can’t ask me that!’

Pierce Brosnan’s wife: ‘I like your tuxedo.’

Me: ‘OHMIGOD THANK YOU SO MUCH THAT’S SO NICE OF YOU.’

Others were less patient. At a red-carpet film premiere in Leicester Square, I commented on the suaveness of a male actor’s suit as he walked past.

‘I’m here promoting my film and all you can ask about is what I’m wearing?’ he said, spitting out the words in a fit of pique. To which I should have responded, ‘Mate, that’s what women get asked all the time, I’m just levelling the playing field.’ But I didn’t. Instead, I flushed furiously and felt humiliated and left without seeing the film.

The truth was, at the age of twenty-two, I didn’t have enough confidence in myself or my own opinions not to let incidents like this get to me. My sense of self was unmoored, at the mercy of any passing gust of wind. This was the age where my people-pleasing kicked in to a higher gear. Like many young women, I mistakenly thought that the best way of feeling better about myself was to get other people to like me and to attempt to survive on the fumes of their approbation.

For someone who spent her twenties in a series of long-term relationships this was terrible logic. I would contort myself into varying degrees of discomfort simply to fit in with someone else’s life, someone else’s desires. It got to the stage that if a boyfriend asked me where I wanted to go for lunch, I became paralysed by indecision. I didn’t want to tell them where I wanted to go in case they preferred somewhere else. After a few years of this, I genuinely no longer knew what I wanted to eat anyway and so actively needed someone else to make the decision.

I lost myself in the rush to be part of a couple.

As a result, I was scared by the notion of not being in a relationship. The longest I was single between the ages of nineteen and thirty-six was two months. In those two months, I came up with every excuse I could to keep in touch with my ex-boyfriend, and simultaneously tried to distract myself by saying yes to any man who crossed my path and expressed even the mildest interest (years later, when I told a male friend of mine about this period in my life, he replied with ‘Fuck. I wish I’d known you had no standards back then,’ which wasn’t exactly what I meant, but it wasn’t far off either).

During these eight weeks, I engineered the least spontaneous one-night stand in the history of random hook-ups, purely because I believed that having a one-night stand was exactly the sort of thing I should be experiencing in my twenties.

The man in question was called Mike and lived in Paris but had come to London for the weekend. We spent an evening eating overly complicated Chinese food served on wooden platters and then we danced in a terrible basement club off Oxford Street that only played salsa music and had stains on the walls that looked like faecal matter. Mike was perfectly nice but had the unfortunate quality of becoming less attractive the more time I spent with him because he said things like ‘Golly gosh’ and ‘Is that the time? Best be getting on then.’ But so intent was I on having this much-lauded sexual experience of no-strings-attached, shirt-rippingly intense bodily contact with a near-stranger, that I insisted on going back to his hotel and falling into bed with him. It was, hands-down, the worst sex of my life. At one point, I had to ask ‘Are you in?’ because amidst the fumbling-golly-gosh embarrassment of it all I honestly couldn’t tell.

As soon as it was over (he had, it turned out, been ‘in’) I gathered up my clothes, locked myself in the bathroom and got dressed.

‘You’re not staying then?’ he asked plaintively when I emerged.

‘No … erm … deadlines … so sorry … lovely evening …’ I said, backing out of the door like a faithful retainer leaving an audience with the Queen. ‘Speak soon!’

Outside, I took out my phone and called my ex-boyfriend. He answered and said he was missing me. We met the next day and got back together. We went out for another year.

As I walked to the tube in the early hours of that particular morning, I reflected that I had tried my best to live out the fantasy of my twenties, to experience the heady whirl of irresponsible youth and casual sex, and yet, when it came down to it, I’d rather be in a steady relationship and have a bath and an early night.

It felt like an extended metaphor for the whole decade: that shifting tension between where you wanted to be, where you thought you should be and where you were right now.

It was the same with work. The Londoner’s Diary was great training for spotting a story and writing it to deadline, but I was desperate to be getting on with the business of being a ‘proper’ journalist.

I was in a job in the area I most wanted to have a career – journalism – but it wasn’t the one I was really after, and it would take me several more years to get there.

I was in a long-term relationship that wasn’t serious enough to lead to marriage and wasn’t fun enough to be casual.

I was in a house-share that, on paper, should have been a place of hedonistic excess but was mostly just a nice terrace inhabited by people who reminded each other of the need to buy toilet roll and made tray-bake brownies from Nigella’s latest cookbook when they had a spare couple of hours on a Sunday.

It didn’t help that there was so much cultural baggage around one’s twenties. When this particular decade was represented on screen, it looked as if everyone else was having a fabulous time. The mood music of my twenties was provided by the Friends theme tune and the clatter of Sex and the City heels on New York sidewalks. But it never translated into real life. The rest of us who didn’t hang out with their closest pals in Central Perk coffee shop or drink Cosmopolitans and discuss the female orgasm were left labouring under the misapprehension that we were failing to make the most of it.

I remember my twenties being a decade in which no one talked – not really, not honestly – about the things they felt unhappy about or the stuff that was going wrong in their lives. It was, instead, ten years of trying to put on a good show – for yourself and for anyone else who might be watching. It was ten years of moving forwards while groping blindly for the point of it all; ten years of building a career but feeling impatient at the lack of pace; ten years of wondering who you were meant to be dating and how you would find the mythical right ‘one’; ten years of casually assuming you had all the time in the world while knowing you were running out of it, to the extent that turning thirty seemed to me to be a giant cut-off after which I would never be truly young again.

One of the most interesting revelations that came from the How To Fail podcast was how many other people struggled with this period of their life. I’d assumed that my interviewees would have nightmare tales to tell of adolescence (I’d been preternaturally well behaved as a teenager, and I expected others to have misbehaved for me) but actually, it was their twenties that came up again and again as a time of immense transition and uncertainty. Unlike me, who had been lucky enough to know what I wanted to do professionally, many of those I spoke to had had little idea of what their future held, and that brought its own challenges.

The writer Olivia Laing chose the entirety of her twenties as one of her failures, because she dropped out of university.

‘I completely fucked up my twenties,’ she said. ‘I went to university for a year and then I dropped out and lived on road protests. So I was a dreadlocked, incense-smelling hippy really. I completely dropped out of society. I was very non-material …

‘Then I really didn’t have any money. I was working as a cleaner, I was working, doing the filing for an accountant. And I was in my late twenties, and I couldn’t see any way out of it … It’s very hard to drop back in [to society] again. So yeah, it was a very, very dark period. And a very long, dark period.

‘You know, at the time I thought, “What does a degree matter?” And I just hadn’t really realised the entire infrastructure that going to university builds for you in your life. It’s not just education, which I think I sort of patched together on my own anyway. It’s that you don’t have a circle of friends that are also doing things. You’re not part of that sort of professional world at all. And the older I got, the more it became clear that I really slipped between the cracks somehow. And it is so hard to get back in.’

Phoebe Waller-Bridge struggled to get the parts she wanted at RADA and felt so broken down by her tutors that she lost confidence and spent much of her twenties failing at auditions or being typecast as the posh, hot girl until she began writing her own material.

Sebastian Faulks recalled being ‘optimistic as a child. So although very shy, I was essentially a jolly little chap. I looked on the bright side. And I think I became essentially pessimistic in my twenties really. And you know, I’ve had to fight pretty hard to try and look on the upside. But I think … I’m not sure it’s a terribly intellectual thing. I think it’s more of a temperamental thing. My physiology or temperament or whatever word you want to use. And the place where they meet, perhaps, is naturally a touch on the gloomy side. So I do have to try pretty hard to be optimistic.’

We were talking in one of the expansive rooms in Faulks’s beautiful Notting Hill home. The window gave out onto a long garden, bordered by rose bushes not yet in flower. Faulks sat in a chair, surrounded by piles of books, and every now and then our interview would be interrupted by the skittering sound of his dog’s feet on the parquet. Faulks had been mildly amused by the idea of my podcast series and wasn’t quite sure what I was trying to get at by doing it or that he’d have anything of interest to say. I’d told him that was my responsibility: I’d have to ask the right questions.

And so I pressed him on what had been going on in his twenties to cause that change in outlook: the shift from optimism to pessimism, as he described it.

‘Well, at Cambridge, which I didn’t like as well as not liking school, I just sort of struggled to adapt really to fit in academically … I was still quite competitive in some strange way and I thought perhaps I ought to get a first, and I ought to do this, and that … I was just confused and I drank too much and smoked too much and became very confused and unhappy. And I dropped out really, I suppose you’d say. And I was aged twenty-two or -three and I was extremely confused and very fragile and it took quite a lot of time to get over that. I wouldn’t say I have got over it really.

‘I mean, life is a continuous negotiation really with yourself and other people and company and the kind of company you want, how much company you want, how much you want to give, how much you want to take, what form and shape that takes. Especially if you’ve had this tremendous shyness as a child [and] still have to some extent. You know, you do change, that’s another thing you’re negotiating, the actual changes that take place in you, the different ways that you react as you get older, to people, families, situations, friendships and so on.’

Two things struck me about this answer. One was Faulks’s sense that he ‘ought’ to be feeling a certain way and doing certain things in his twenties. The other was the significance he attributed to change, at a time when many of us are negotiating not only salaries and rent deposits but relationships with partners and families too. We are half child, half adult, with a foot in both camps. We lack the innocence and irresponsibility of childhood but most of us don’t yet have the skills to navigate adulthood because our identities are still being shaped.

I was born in 1978 and am a classic Generation X-er. My mother was part of a 70s generation who fought feminist battles for their children’s future, but who also belonged to a traditional domestic set-up where the lion’s share of household duties – including raising children – fell to the women. When I went to my all-girls secondary school I was taught that I was not defined by my biology. In fact, the majority of my sex education (such as it was) was focused almost entirely on the importance of not getting pregnant before you had established yourself in your career.

So I entered my twenties with a series of mixed messages. I knew it was important to forge a professional path. But I also expected to be married before the decade was out. I think that’s why I kept finding myself in serious relationships, rather than having a more relaxed attitude to intimacy, and it’s also why my twenties were pretty busy and stressful: not only was I trying to carve out the perfect career, but I was also attempting to nail down a perfect romantic partnership. As time went on, I felt I was failing at both. I was impatient for everything to be sorted and I didn’t realise that your twenties are a time of transition, of flux and that being in the change is the point of them.

As a result, I struggled.

For millennials, who entered the job market at precisely the time the 2008 global financial crisis struck, it must be even worse. They have been brought up in a hyper-connected age where everything from dating to grocery shopping can be done online, where contemporaries are boasting about their amazing lives on social media, where rents are high, property prices astronomical and where job insecurity is rife. There’s a scene in Lena Dunham’s Girls, the millennial sitcom of choice, in which Dunham goes in to get tested for an STD and her gynaecologist sighs, ‘You couldn’t pay me enough to be twenty-four again.’ Dunham’s response is, ‘Well, they’re not paying me at all.’

But some things are universal whatever generation you belong to. Most of us will experience the loss of loved ones in our twenties. My maternal grandfather, to whom I was very close, died in my second year at university. When I was twenty-three, that beloved former boyfriend who kept eating all the food I bought, was killed in Iraq where he had gone as a freelance journalist to cover the conflict. It was a shock from which I have yet to recover and I suspect it’s the kind of shock from which one never does. A few years later, a colleague of mine who battled with alcoholism was found dead on the floor of his flat. I lost my paternal grandmother shortly afterwards. Many of us will have similar stories: your twenties are often when you first come face to face with mortality, with the sense that all of us are, to a lesser or greater degree, running out of time.

It was the decade I first went into therapy. My friend (also in her twenties) passed on the number of her therapist and when I called, the phone rang out and clicked into voicemail. I had intended to leave a short message with my details but ended up gulping back the tears while I tried to explain what was happening in my life, all the time being hamstrung by British politeness and a sense that I was being terribly self-indulgent.

‘I’m not exactly where I want to be professionally,’ I said. I was standing in the corridor of my office when I made the call, surrounded by copies of old newspapers and the sound of the ladies’ lavatory door clanging shut. ‘It would be great if you were able to see me.’

For the next three months, I went to an office in a red-brick house in Queen’s Park, north-west London, every Wednesday morning before work. My therapist was an attractive woman in her late forties with shoulder-length greying hair and a penchant for statement Bakelite necklaces. She would open the door to me when I arrived and not say anything to me beyond a cursory hello, and I would follow her up the stairs trying to make agonising small talk until I realised after a few weeks that there was no point in trying to charm her. The awkward silence was part of the therapy. It was about making me feel comfortable with being uncomfortable. It was about making me choose honesty without worrying about what she would think of me and whether she would like me or not.

Her therapy room was kitted out, as I have since discovered, like almost every therapy room I’ve ever been in: anonymous Ikea furniture, a generic pot-plant, a box of tissues on a low table and a subtly placed clock so that you can see when your session is coming to an end. Within those four walls, I made some interesting discoveries. One of them was that your twenties could be a ‘gestation period’.

My therapist would couch her opinions in a series of questions, designed to make me feel I’d cleverly come to conclusions about my own behaviour by myself. And so it was that one day, she said: ‘Do you think that maybe, you’ve been through quite a lot already and been operating at a fairly frantic pace, and that perhaps this is a necessary time of reflection, of allowing the next phase to hatch?’

It was an incredibly helpful moment. It allowed me to let go of some of the ‘oughts’ and the ‘shoulds’ that had been crowding out my thoughts, those shrill internal critics that were taunting me with the idea of what other people were doing and how I was failing to keep up. I relaxed a bit.

At my thirtieth birthday party, held in an upstairs room at my favourite pub with a playlist designed especially by me and full of 1990s hip-hop, I felt happy. In fact, I felt relieved to have made it through my twenties and relieved that I no longer had to worry about turning thirty. It was done. I was a little bit wiser. A little bit more self-aware. In a few months’ time, although I did not know it then, I would sell my first novel.

Looking back now, I suppose I would categorise my twenties as a decade of impatience, where I wanted to be at the mythical happy end point, but had to sort through a whole lot of stuff to get there. They were also a decade of worrying I wasn’t doing them right, that I wasn’t being footloose enough or responsible enough and that, caught in the unsatisfactory mid-point between the two, I was failing to make the most of them.

The author David Nicholls, who spent most of his twenties trying and failing to make it as an actor before turning his hand to writing, said that he now realised ‘there are ways out, that we’re not fixed at the age of twenty-two, twenty-three, that life is long and you can try things for a while and if they don’t work out, do something else’.

But of course, it’s only when we’re older and have knocked about a bit that we can conclude there is no uncomplicatedly happy end point. There are a series of points – some happy, some sad, some simply quietly contented – and each one will be different from how we imagined it. Not better or worse; just different. And perhaps what surviving your twenties makes you realise is that life, after all, is texture.

‘I feel like I did it [my twenties], I committed to it,’ Phoebe Waller-Bridge said when I spoke to her about her own decade of transition. ‘I’d really like to have the skin from my twenties,’ she joked, ‘but I prefer my heart and my guts now.’

That’s the thing. Because however much you might feel you’re failing at your twenties when you’re living through them, they are a necessary crucible. Your twenties are spices in a pestle and mortar that must be ground up by life in order to release your fullest flavour. By the end of them, you’ll have more heart and more guts – and you’ll know never to roast broccoli again.