Читать книгу This Fight is Our Fight: The Battle to Save Working People - Elizabeth Warren - Страница 13

YOUNG DREAMS

ОглавлениеIn the spring of 1966, when I was sixteen, I started going home every day for lunch. The house was empty, because Mother was working at Sears and Daddy was out selling fences. But I wasn’t there for company; I just wanted to check the mail.

I had found two prospective colleges, one by searching through a book in the high school counselor’s office and one through a boy I knew; both schools bragged about their debate scholarships. I was a good debater—on my way to the state championship—and I figured that was my chance. So I’d taken the cash from babysitting and waitressing and bought two money orders from the 7-Eleven to cover the two application fees, then played the waiting game. I was putting all my chips on the hope that one of those places would give me a big enough scholarship to make it possible for me to go to college. And now I was praying that one of them would come through.

By that spring, college was all I could focus on. Ever since I’d been a little girl, I had wanted to be a teacher. And no one gets to be a teacher without a college degree.

For weeks, nothing turned up. Friends were getting their acceptances and starting to talk about which dorms they would live in or what majors they would declare. And I kept going home for lunch.

One day I dashed out of history class the instant the bell rang. As I came around the corner onto our street, I saw the red flag up on the mailbox, signaling that we had mail. Inside lay two fat envelopes, one on top of the other. I stood in our front yard and tore into each one. The first letter was from Northwestern. The university was offering me a scholarship, a work-study job, and a student loan. I quickly did the calculations and saw that I would still need to come up with maybe another $1,000 or so each year—an amount I could just about cover with a summer job. This was it: I could go to college. For sure.

Then I ripped open the second letter, from George Washington University, and—wow!—it was offering a full scholarship and a federal loan. That was all I needed to know: then and there I decided to become a GW Colonial. I had never seen either school, and I didn’t know how I’d get to Washington or where I would live, but even so, I was headed to GW!

I sprung it on my parents that night. They already knew about the applications, but no one had said anything for months. We’d all been waiting, just tiptoeing around until the news came in. Now I was dancing around the kitchen big-time, waving the forms and talking about the humongous size of the scholarship (or, at least, that’s how it seemed at the time). Daddy grinned. Good on you, punkin.

Mother was more shocked, but she recovered. College—and a way to pay for it—was now possible. Within days, she told every grandparent, aunt, uncle, cousin, neighbor, grocer, dry cleaner, preacher, and person she met on the street that I was going to college. She always noted that she didn’t want me to go so far away, then explained, “Betsy figured out how to go to college for free, so what could I say?” I think she invented humblebragging before others perfected it into a fine art.

And just in case I was about to get a swelled head, she usually added, even with the news about the scholarship, “But I don’t know if she’ll ever get married.”

On Labor Day weekend before I headed back for my junior year at GW, my first boyfriend (and the first boy to dump me) dropped back into my life. He was now twenty-two, a college grad with a good job, and evidently he had decided it was time to get married. He proposed, and about a nanosecond later, I said yes. At nineteen, I said hello, housewife; good-bye, college. It was definitely not the smartest move I ever made.

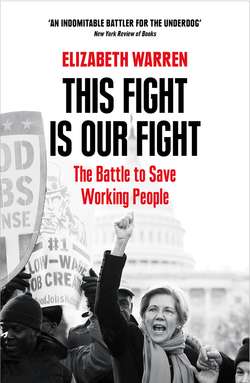

Me as a college student, ready to take on the world.

But I was living in a time of second chances, and I got lucky again. Even a girl shortsighted enough to give up a full scholarship could get back in the game. Before long, I was back in school, hitting the books at a commuter college that cost $50 a semester. This was an education I could pay for on a part-time waitressing job. I saw that chance, and this time I was smart enough to grab it with both hands and hold on for dear life.

Two years later, I got my first job teaching special-needs kids.

COLLEGE IS THE way up—at least, that’s what we believe. For me, college was a chance to fly.

But for today’s college students, flying is a whole lot harder. Every time I talk with a college student today, I’m reminded of how lucky I was and how much has changed since I was stutter-stepping my way toward a college degree all those years ago.

I was introduced to Kai through a friend. In October 2016, we agreed to meet at a restaurant within walking distance from my house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Kai was in her late twenties. As she stood up from the table to say hello, I was struck by her eyes. She was lively and interested in everything around her. She commented on the restaurant, the menu, the silverware, the dishes, the light in the room, the drawings on the wall—and that was only in the first five minutes. Tall and dark-haired, she was an impressive young woman, the kind who could take on the world and succeed anywhere.

She was more than willing to tell me her story, but she didn’t want me to use her real name because she was embarrassed about how things had turned out. We agreed that I’d also change some details of her story to protect her privacy.

Kai grew up in Colorado. Even as a kid, she’d had a plan about her future. Her dad was a firefighter, and they loved spending time together playing computer games. It was their time. She explained that she had been playing video games “since as long as I could walk.” She knew she wanted to create those games.

Kai was interested in what she saw on the screen, but as she learned more about the science and art underneath those graphics, her interests expanded. From ATMs to airline check-in kiosks to advanced medical imaging equipment, front-end designers are now walking people through more than just games; they now lead people through events across our economy. Kai knew that if she got the right education, she could land a career in a field she had been training for since her daddy lifted her up for her first game.

Neither of Kai’s parents had gone to college, and she didn’t get college counseling from anyone in her high school. She was pretty much on her own to figure out what would be the right school. She didn’t want to study art theory in a big lecture hall. Instead, she wanted hands-on work and sophisticated training that would prepare her for a real job.

Kai worked hard in school, but that wasn’t enough.

When she saw a TV commercial for the Art Institutes, a nationwide system of art schools, she thought, “This is it!” The promotional materials were amazing. “One of the deciding factors for me choosing to attend the Art Institute,” she explained, “was its focus on being a ‘career college’ that didn’t deal with the typical four-year-college experience driven by fraternities or social events.”

Kai now blasted off full speed ahead. “I wanted to be surrounded by professional artists and designers, all aiming for the common goal of making it into the industry with focus and determination,” she told me. Her older sister lived outside Seattle, so Kai worked out a way to move in with her and save on expenses when she enrolled in the Art Institute of Seattle (AIS). She was ready to take on the world.

Kai’s first two years in college were a lot tougher than mine. She got up at five o’clock every morning to catch a ferry to Seattle and then ride a bus to the school. She saw two years of sunrises, but she never complained about the early hours or the long commute. She was a little uneasy about whether she was learning the cutting-edge material prominently featured in the promotional materials, but she loved being around computers and working with graphics. To support herself, she worked part-time at Barnes & Noble. Even so, she kept her priorities straight. She attended every class and did every scrap of homework. Kai was proud of her 3.9 GPA, and she was determined to keep it up.

Sometimes on those long commutes, Kai thought about her finances. She knew she could do the classwork at AIS, but by the time she reached the two-year mark, she had already run up $45,000 in student loans. That was a lot of money.

Early in Kai’s third year, the whole thing came crashing down. The Art Institute of Seattle wasn’t like the state schools back home. It was one of fifty college campuses around the country owned by a multi-billion-dollar corporation. That corporation, Education Management Corporation, and its highly paid executives were looking to haul in big bucks for themselves and their investors by scooping up Kai’s federal student loan money.

Kai hadn’t known it when she’d started out as a freshman, but the Art Institutes were in trouble. Complaints about fraudulent promises, fake records, and programs that didn’t deliver were piling up. The Justice Department opened an investigation, and by Kai’s third year, her program began falling apart. Faculty and staff members were laid off. The program’s reputation took a nosedive. People said the credential it conferred was useless. Kai heard that AIS was shutting down the program, and she panicked. She was worried that even if AIS survived, her diploma might not be worth anything. Besides, she didn’t want to lose a year, so she went into high gear, determined to find another school in a hurry.

Kai was doing work she really loved, and she was more committed than ever to getting her degree in video game art and design. When she discovered the program at Ringling College of Art and Design, in Florida, she decided to pull up stakes and go. She would have to move across the country, and she wouldn’t have her sister to provide free housing, but her enthusiasm bubbled over. “There were more resources, more connections and opportunities,” she explained. “It was more of an Ivy League, as far as art schools go, and so there were possibilities of putting money into endeavors that supported the students’ success.”

Kai packed her belongings, kissed her sister good-bye, and headed across country to Sarasota, Florida. New school, new program, new part of the country. She could take it all on. But the one part that made her hands shake was the cost. While Ringling wasn’t part of a big for-profit company, it wasn’t a public school either. As a private school, its students have to bear all the expenses. Kai took on another $30,500 in debt to pay for one year. That was on top of the nearly $55,000 in debt from AIS.

She loved the classwork, but she couldn’t finance a second year. She just couldn’t do it. Kai hated to leave Florida, but she refused to give up. Instead, she moved back home and started attending classes at the University of Colorado. That school didn’t have the same video-design programs, but it was much less expensive. She figured that she’d spend a year at the University of Colorado, get her degree, and then land the job of her dreams. Okay, she might not get her dream job right at the beginning, but she felt certain that she was born to work in the gaming industry and that once she got in the first door, she could kick open other doors for herself. Over time, she would pay down her student loans and start a real life.

Only there was just one small hitch: she needed yet another student loan to attend her new college. So she added another $13,000 to her debt load, which pushed her total to about $100,000. And because she had hit her maximum under the federal loan program, she now owed money to both the government and Wells Fargo.

During her last semester at the University of Colorado, when she thought she was just a few weeks away from graduation, the registrar’s office informed her that most of the credits from her first two years at AIS wouldn’t transfer. Students like Kai often find out too late that for-profit schools like AIS don’t meet the standards set by accreditors of state colleges and universities. After some back-and-forth, the university’s administrators explained that she would have to attend the school full-time for two more years before she could earn her diploma.

Kai hit the wall. After years of sacrifice and hard work, completing college suddenly seemed out of reach. “I couldn’t afford it,” she told me. “Wells Fargo wouldn’t give any more, my parents still couldn’t afford it, and honestly, at that point, I was done.”

It was also a personally difficult time. Kai’s dad was dealing with brain cancer, and the pressure was more than she could bear.

Kai didn’t finish the semester at the University of Colorado, and she never got her degree. So where is she now? She is twenty-seven, living with another sister in Connecticut, waiting tables at an Italian restaurant. She puts every penny of her paycheck toward her loans—literally every penny. “If it wasn’t for my family,” she says, “I would be homeless and poverty-stricken.” And even with this level of commitment, and after five and a half years of payments, her loan balance is still over $90,000.

This is the point in the story when all her apparent confidence drains away. Her hands drop to her lap, and she looks down at the table: “I’m the poster child for what not to do.”

KAI PLACES ALL the blame on herself, but I don’t see it that way. Kai was doing exactly what everyone told her to do: work hard and get a good education. She didn’t goof off and party. She kept her grades up. She had good recommendations from her professors. She had chosen a career path that promised a good job. Yes, she would have been better off if she hadn’t been taken in by a for-profit college and then set her heart on attending a high-priced private art school. But I don’t put all of that on the shoulders of a seventeen-year-old high school senior trying to figure out how to build a future.

Of course, Kai would also have been financially better off if she had been born into a family that could shell out $100,000 for her education—but I don’t put that on her, either.

Kai now joins the millions of Americans who have incurred student loans—some of them monstrously big—and have no diploma to show for it. And even when these young people do have a diploma, that alone won’t always do the trick. One and a half million people over age twenty-five have college diplomas but no jobs.

Kai’s story speaks of everything that’s broken with American higher education. She went through a college search process that runs on parallel tracks: rich kids benefit from parents who can work their connections and hire expensive coaches to help them make perfect matches with perfect schools, while middle-class kids like Kai get a hearty “good luck” from an overworked guidance counselor. After graduating from high school, Kai got snared in the trap laid by for-profit schools. These places are pulling in one out of every ten people who go off to college, getting them signed up for huge federal loans, and often leaving them with little to show for it. Even when Kai finally made her way to a terrific state school, she came smack up against the hard reality that the school still cost more than she could afford.

Years ago, I got lucky with my scholarship. Later, when I returned to college and earned my degree, it cost me only $50 a semester. I grew up when America was investing in education and keeping the doors open wide for any kid who had the pluck to come in and do the work. But since the mid-1970s, the cost of an education at a state school, adjusted for inflation, has quadrupled. And it shows. Today, two-thirds of kids in state schools must borrow money to make it to graduation.

Ah, the debt. The bone-crunching, never-ending debt. Kai works every day just to tread water on her student loans. Her $90,000 adds just a tiny bump to the giant ball of outstanding student loan debt nationwide. She has joined an army of Americans who are struggling to pay back money they borrowed to get an education. The way I see it, every happy-face story about this economy should include a footnote that tags this fact: forty million people are trying to figure out how to pay off a combined $1.4 trillion in student loan debt.

That debt is toxic in more ways than one. It casts a huge shadow on a person’s credit report, driving up the cost of everything from insurance to a home mortgage. And unlike a home mortgage, student loans can’t be refinanced when interest rates drop. And unlike casino loans or credit card debt, these loans can’t be discharged in bankruptcy when the borrower can’t pay.

The loans can also chop off big parts of a former student’s future. In Kai’s case, they kill her opportunity to take out a mortgage to buy a home. They kill her chances to borrow more money to go to school and finish her degree. Without that degree, those loans kill her dream of getting an entry-level job in a business that employs people with a degree in visual arts. And she can just plain forget about building up a little savings, buying health insurance, or stashing away some cash for retirement.

Kai still sees visual arts as “her field.” But will she ever work there? Her answer is short and defeated: “No.”

Kai and her friends were born into a country that told them to work hard in school, get a good education, and the world would be theirs. But a grim new reality is starting to sink in: they can work their butts off and they still won’t be able to carve out a place for themselves in the middle class.

Kai and her friends have prepared themselves for the future better than any other generation in history. They are more educated: today a higher proportion of young people graduate from high school, graduate from college, and even pick up postgrad degrees. They have more part-time work experience from their high school and college years. They are computer savvy, and their experience with technology often makes them teachers rather than apprentices to people a generation older.

As young people enter the job market and begin to put shape to their lives, they should be flying high. But they aren’t.

The unemployment rate for people sixteen to twenty-four years old who are actively looking for jobs is 12 percent—almost three times higher than for their older counterparts.

The $1.4 trillion burden of student loan debt that’s being carried by those who went to college is unlike any in history—and the amount keeps climbing, at a rate of about $100 billion a year.

For the first time in modern American history, more people between eighteen and thirty-five live with their parents than have a place of their own.

The odds that a young person today will earn more than their parents have gone from a near certainty a generation ago to a coin flip today.

Despite their better educations, today’s millennials earn about 20 percent less than boomers earned at the same point in their lives.

Young people—America’s future—have been dealt a terrible hand. Those who don’t make it through college have little chance of making it into the middle class. And those who make it through college are often so swamped with debt that they begin their adult lives in a deep financial hole. College is the big divide between those who will have a lottery ticket for the middle class and those who won’t, but in the end, even for those who get a diploma, it’s still only a lottery ticket. Millions of college graduates today are unemployed or working at temp jobs or part-time jobs or jobs that don’t require a college degree, trying to get a foothold in an economy that is no longer providing expanded opportunity for anyone who can flash a diploma.

Today twenty-five-year-olds start their adult lives in an economy where the most sustained job growth is in minimum-wage and near-minimum-wage work. Many have no realistic chance of ever owning the kinds of homes their parents purchased or ever starting the kinds of businesses their parents did. Today’s young people may be the first generation in American history to end up worse off than their parents.

Kai’s story breaks my heart—and the unfairness of it makes me want to spit. How can the country that once gave a kid like me multiple chances to do something with my life now shut out a talented and hardworking young woman like Kai? How can any country expect to build a future if there’s no room for a person like Kai to get an education, start down the road toward a good career, and build the foundation of a good life?