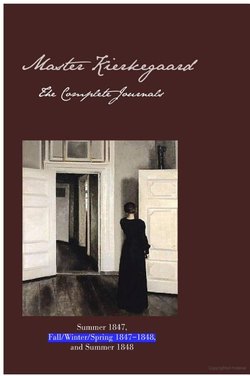

Читать книгу Master Kierkegaard: The Complete Journals - Ellen Brown - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Journal One

Оглавление(May 29–July 13, 1847)

May 29

I, Magda, a servant in the house of Kierkegaard, answer to the younger living son, who is my master. As I am slight of build and not raised up to do the work of a charwoman, my household duties are light, though not supervisory in nature. Mrs. H. holds the keys. I would be a mere chambermaid had my master not taken an interest in my peculiar circumstances and temperament. His inquisitiveness into these matters is most surprising for two reasons. Before coming to work here three months ago, I had heard unkind things said about him in particular, who is known to have a razor-like tongue, while the whole family, though quite wealthy, seems to have lived and died under a curse of some sort. Copenhagen is not so large and sophisticated a town as not to indulge itself in village gossip of a superstitious and petty nature. I know better than to trust entirely in such reports, therefore. More surprising is my master’s capacity for taking an interest in one such as me, not the most unfortunate of women, but fallen in rank and esteem sufficiently to have suffered rudeness and indifference from previous masters. An afflicted person (particularly an unmarried woman) becomes an easy target for those enamored of their little bit of power, but for those possessing both wealth and nobility of mind, a stinting meanness holds no appeal. He is more generous in every way than most people realize. And more kind.

My own pride and memory of my former prospects impel me to make plain the fact that I have not sought the sympathy of my master. He has found me out, not through embarrassing questions that might cause me to dissemble, but through sheer attentiveness—no, I mean attention. He has a way of looking at me that feels as though he is looking through me, though not beyond me as in a vacant stare, but with a piercing gaze that picks up my essence and drives it deeper within, yet also out into the light, where I may see it for what it is, without boasting or shame. I hear he is a terrific critic of others, however, especially intellectuals who pretend to lead the elect to enlightenment by means of the catchphrases2 of the day. I am not surprised. The sharpness of his tongue (or pen) is matched only by the sharpness of his gaze, which cuts through me quite painlessly. But enough of that.

Tonight’s Holy Scripture3 is Matt 13:24–30. Allowing the weeds to grow alongside the wheat until the harvest—what patience this requires! One of my favorite activities is helping the gardener pull weeds. Imagine if we house servants were to let the dirt run its course—alongside the cleanliness?—what nonsense! The weeds, like the dirt, will overtake everything. But I suppose patience looks like foolishness, imprudence, naiveté, to the impatient. The last parable was about a sower sowing seeds. That is my master. This parable is about the servants tending the crop. This is I. And yet we are the seeds and the crop as well. Blessed be God forever!

May 30

Moving about the house today, accomplishing little, wanting to be out of doors, I finally told Mrs. H. I would go for a walk. She consented of course, not being my jailor, but with a worried look. Too much freedom for a servant leads to no good, she has told me before in dark tones. I have heard gossip—not from Mrs. H., who is all discretion, as a person in her position must be—that the freedom of a servant was the cause of this family’s supposed curse. I do not subscribe to primitive notions of cause and effect, though I think if there had been any grievous wrongdoing, the personal guilt attached to it could bring about any manner of unhappiness, illness, even death. Humanity is so deeply moral that it finds ways to punish itself one might not think possible. My master seems bent on some form of penance, though for whose sins is not quite clear to me. And yet he never takes the tone of a preacher with regard to either morality or religion—he is quite clear on the difference between the two. He seems to believe God could command a person to behave immorally and that person would have no choice but to comply. Such thinking frightens me, I confess. I believe my master takes Holy Scripture to heart in a manner most of us would never dare to do, the Old as much as the New Testament, maybe even more so.

Matt 13:31–32. Birds sheltering in the tree that grows from the tiniest of seeds, the mustard. The kingdom of heaven is not the tree, but the seed. Our souls are the birds. Our souls are the fruition of our bodies, in the same way that the tree is the fruition of the seed. When our bodies complete themselves, they will be at ease in the sky. The man who plants the seed is our Lord Jesus Christ. He grows a home for our souls that is rooted in the earth.

I sometimes help the gardener plant seeds and wonder how something that looks so dead could bring forth life. The gardener tells me the seed contains within it not only the pattern of its future life but also all the food it needs until it can take in the nutrients of soil, water, and light. I imagine what it would be like to be the seed, buried in the ground, straining toward the surface. How do people who live crowded together in large cities make sense of these parables, I wonder? Do they have little gardens of their own, at their windows or on their rooftops?

On my walk, feather-like seeds, a steady stream in the sky, followed by a yellow-green wave of finer particles, barely discernible yet pervasive. The whole a flow for long enough to suggest that with stronger vision I might see everything that way. I wish my master would walk out more. Mrs. H. wishes I would stay in more. I asked my master what sort of plant the mustard is and he said, “Irrepressible—a weed, essentially.”

June 1

The Sunday before last was Pentecost. We were called to the altar to renew our baptismal vows and confirmation. I touched the hem of the altar linen and felt a current pass through me, then returned to my seat and wept for all my losses. Was this my healing miracle? No one noticed anything I did, which in our small church is a miracle in itself. My boldness often gets me into trouble, but just as often it is my salvation. My master, who knows Greek, tells me the Gospel word for faith or belief can also mean trust or confidence. It seems different words speak to different situations.

I am reluctant to write about my master. He is a mystery to me and would not wish to be written about, I feel, whether I understood him or not. When he first found me, in the library looking into one of his German books (I cannot read Danish)—I was supposed to be dusting but became curious—he was not angry with me. He did not seem the least annoyed, in fact, at the liberty I had taken. It was Faust, which had fallen open to the garden scene. With a slight smile, my master gently took the volume from my hands, casting a quick glance onto the pages before closing the book and returning it to its place on the shelf. I have remarked already on his manner of looking, accentuated by his awkward posture (unfortunate in such an otherwise elegant man), which makes him seem to stoop to peer at the world from a discomfiting elevation, rather like a vulture, I am sorry to say.

Matt 13:33–35. The kingdom is like yeast that a woman mixes with three measures of flour. Jesus speaks only in parables. This woman4—I identify with her. I help in the kitchen too—all I do here is help because I have no real housekeeping skills of my own, not having been raised to this kind of work. What I was raised to is a good question—for dependence on men, but with sufficient education to make them entirely wary of me. I can learn about this yeast by working with it. Its growth is mysterious, miraculous to the ancient mind, but not the modern (though while I believe science can explain the growth of yeast under certain conditions, I myself do not understand what happens). What is important is the experience, the handling, of warm, soft dough with the expectation of the desired result: bread. Maybe ein Weib understands this better than eine Frau.

June 2

Matt 13:36–43. One minute Jesus speaks only in parables and the next he is explaining his own parable (the one about weeds). But he is at home in this scene. Maybe he only speaks in parables in public, so that those who would kill him cannot quite be sure what he is talking about. Goethe has his Doctor Faust say that those few who knew something of the goal of knowledge who were foolish enough to bare their hearts to the people have always been crucified and burned5 (yes, I have been back to the library). Jesus knew this as well as anyone. He was cagier than most, and yet he also understood the goal of his existence—death for the sake of life outside time. This “harvest,” Jesus says, is the work of the angels.

If people, Christian people, really believed this, then death would not be a curse. I wonder what my master really thinks about death. He seems to believe in this family curse—only he and an older brother surviving of seven children—as much as anyone. The town talks of the father having been a pious man, a devoted parent, perhaps less devoted as a husband (the first wife died childless), but nonetheless an excellent provider and a model of fidelity to his second wife, my master’s mother—though as a former servant in his house and a distant cousin, I understand, she never rose to the rank of a true wife and matriarch. In short, she never gained her husband’s respect. But she had my master’s love—I can tell from Mrs. H.’s remarks, which she lets out from time to time with a sigh, absent-mindedly, as though there were no one to hear her. She does not talk to herself on other topics, only this—how much our master loved his mother, a former servant in the house of Kierkegaard. “The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect from his realm all who give offence and who do wrong and will throw them into the furnace.”

June 3

On my errands I found a dog lying in the gutter—run over by a vain and careless driver. A pedestrian had pulled the poor creature to the side to prevent its being struck repeatedly. Bleeding from both ends—I cannot get the sight out of my mind. My master, noticing my red and swollen eyes this afternoon, asked what was the matter. I told him what I had chanced upon and said I stayed, looking on helplessly, until the trembling animal died. He looked at me in his characteristic way for quite some time, and then said, “There is only one way to understand the suffering and death of the innocent. They are selected by God for the sacrifice.” “But what of the carelessness of people?” I asked. And he answered, “They will be dealt with in time.”

I now understand why my master was never ordained. He is too honest to be a minister. Most Christians are not comforted by truth. How ironic, when our Lord taught us that he is the great liberator by being the embodiment of truth. Perhaps people do not wish to be liberated from falsehood. And I cannot blame them, really, when I consider that our choice is between being sacrificed and being punished, unless, as ordinary people who are neither entirely innocent nor inveterately wicked, we repent and seek the narrow path of faith and love.

When I find myself overcome with evil, I think on our Lord’s mother and what she must have felt, and I pray to her that all the innocent may be allowed to live free and happy, as I am sure she would have them do, and the wicked may be relieved of their impulses, and the rest of us may live in peace. Why this machinery of good and evil, in which all creation is ground to a pulp? To teach us forgiveness?

Matt 13:44–46. Or to teach us what is truly of value—like the treasure in a field or the precious pearl, buried or locked away in nature’s vaults, which only great effort and expense will secure? The heavenly kingdom has its own resources and economy so unlike our own, and seemingly so unjust at times. It is the injustice that makes me angry, and the anger that stays with me. Mother Mary help me!

June 4

I woke up this morning with a heavy head and went down to the kitchen to help, but Mrs. H. sent me right back up to my room with a bit of bread and a cup of steaming broth telling me to keep my cold to myself. She has learned from her midwife-friend that colds and fevers can pass from one person to another, even through a healthy person, though she says doctors do not seem to know this. They go from the bed of a patient who is seriously ill to the bed of a healthy woman in labor and soon the mother is dead of childbed fever. Midwives attend to only one mother at a time. Mrs. H. says the midwives have long noticed that the doctors lose many more mothers than they do, but neither the doctors nor the fathers who hire them seem to notice or care. “The arrogance of men,” she said with some heat, and I thought, “the bitterness of women,” but kept that to myself.

Along with the dinner left at my door this afternoon there appeared the volume I looked into a few days ago containing Faust. My master’s contribution, as neither Emil nor Mrs. H. would recommend such reading. He does not wish me to be lonely or bored. I feel a fever coming on and wonder how this fantastic seduction is likely to affect my addled brain. Perhaps this is an experiment on the part of my master. He is so curious about everything, and to me, likewise.

My mother died of childbed fever soon after giving birth to me. In addition to being something of an orphan and, one might say—metaphorically, at least—a widow, I am also an alien. Like Ruth, I meet all the criteria for the mercy which does not seem at all characteristic of the northern European Christian temperament. This is not self-pity, but honest self-appraisal, along with an unflinching indictment of my brothers and sisters in Christ. I find the Danish not that different from Berliners. I say not self-pity, but then illness does cause one to feel a bit sorry for oneself, as it heightens ongoing affliction. I have never felt I held a proper place in this world, and being ill I feel it more strongly. “A small death” I have heard illness called. The advantage of deadly disease is twofold: one’s self-cherishing is no longer exaggerated when it quite suddenly becomes short-lived. The dying person has a moral superiority and even spiritual acumen that no sane person could possibly envy, and yet the benefit is real—perhaps a recompense for what is to be lost. Most dying people do not know how to use it, however. I like to think that if I were dying I would know all the right things to say to my father. And I would greet our Lord with the deepest gratitude for having released me into the hands of my mother.

Faust confesses to his attendant Wagner6 that his perseverance in medieval medicine, in keeping with the training provided him by his father, actually did more harm than good to the simple people he tried to help—the cure worse than the disease. The magic coat Faust wishes might carry him to unfamiliar lands, to be singled out from humanity as Joseph was from his brothers, who then sold him into slavery—another mad dash out of the rain into the gutter.7 What does this two-souled man, panting after heaven and earth in the same breath, really want, and whom will he not harm to get it?

June 5

A little better this morning.

Matt 13:47–51. The scribe who becomes a disciple of the kingdom of heaven is like the head of a family who hauls out of his storehouse both new and old provisions. Jesus liked scribes better than Pharisees. There was hope for the scribes, men of letters, but no hope for the Pharisees, men of the cloth (Matt 12:38–45), that they could be renewed by a new set of writings, a new teaching.

Faust is a tragedy of failed covenants and false promises. I wonder what sort of writing my master is doing at this moment.

I dreamt last night that I was a prisoner and that my guards (or guardians—I am not sure which) were dogs. I rarely remember my dreams, but I awoke in the middle of the night when the fever broke and the dream was fresh in my mind. So I made a mental note of it before I fell back asleep and did not recall it until a few minutes ago. Mrs. H. has sent word to keep to myself until tomorrow, when I can be useful again. In the meantime, more Faust.

June 6

This morning’s sermon: a ramble on everything to do with God. The minister, a young man, prides himself on his ability to preach without notes or an outline in front of him. As a result, though, he manages to repeat himself endlessly without, however, establishing a focus, which makes it impossible to stay on topic. Such argument as manifests is familiar and predictable to the point of utter banality. My master’s elder brother is a pastor, but he (my master) has little use for the clergy due to some past disappointment—so many in this family!

We Christians are called upon to put our faith in one another as well as our Lord (though not to the same extent, I trust), and particularly when it comes to the ordained. This can result in tremendous expectation and letdown. As a woman I have an advantage; it is evident to us that men set things up for their own edification, and so I would never imagine that my spiritual growth is their objective (the clergy’s, I mean). But my master, being a man, believes he has every right to expect utter sincerity from Bishop So-and-So, whose interest lies in the wealth rather than the well-being of my master’s family.8 Most servants are of a better sort than religious authorities, I find, though there is rot in every profession.

Matt 13:53–58. “A prophet is nowhere worth less than in his fatherland and his own house.” Jesus’ works are dependent on the faithfulness of those on whom he works. Those who do not take him seriously never really know him. My master has the brilliance and daring (and anger) of a prophet, and so people fear him mostly, but with fear comes the need to discount. Perhaps he has a tendency to discount himself, being the youngest. No one expects anything of the youngest, so that when they do make a mark, it is an affront, to be dismissed as effrontery.9 I prattle on here worse than a preacher. The Lord’s Day is not set aside to be filled up with words.

The clouds this afternoon look like the flow of a glacier in spring, white opening into blue. The birds sing so sweetly in the trees. I never learned the names of birds and trees in my youth. This puts me before (or behind?) Adam, who could not rest easy until he had named everything, including Eve, I suppose. Now it clouds over; the contrast is lost.

June 7

My strength comes back through honest effort, washing woodwork and windowpanes. One must be well to read Faust and not succumb to its seductions. The language, the variety of verse forms, the subject matter, any of these things alone is enough to make one swoon.

June 8

I see little of my master. He stays to himself while he works or else goes out. He has a reputation for witty, even brilliant conversation—maybe monologue would be more accurate. He entertains sophisticated Danes with satirical talk, but they would not be his friends. His only friend is Emil. There are no ladies in his circle, as far as I can tell, though there was once an engagement, of which we are forbidden to speak in this house or on the street. Part rake and part saint, he is a lonely man. The one thing my master is not is the self-interested Bürger, obsessed with war and taxes, casually ridiculed by Faust,10 and so familiar to me from my youth. As a girl, however, I did not realize how dangerous this Bürger-mentality is, all blood and treasure, treasure at the expense of blood. My master, as cynical as he may seem (or be, for that matter), knows where his treasure is laid up. He has renounced the pursuit of money and worldly honor for the sake of wisdom and grace. That to me is courage. But of course his father’s relentless pursuit of wealth and uncompromising avoidance of luxury (an asceticism resulting from the perception of some wrongdoing—the family curse again) has made my master’s seemingly contradictory course possible. A modern saint is a living contradiction, yet all saints are modern, witnesses to the moment in which they live. I believe in him, and he senses this.

I have doubts about keeping this journal though. It seems like a waste of time. I have no story to tell, or rather no story worth telling. I never was fond of involved plots. My days are boring and empty, and that is fine by me, though I fear getting lost in the vacancy of my life. But writing is a balm, a mercy, a way of being simple: pen to paper, thought by thought, impression after impression. Perhaps I should spend more time praying and less time writing, but simply to breathe conscious of a world of suffering is prayer. Otherwise, how could we pray always, as our Lord enjoined us?11

Matt 14:1–12. The “fury” of “a woman scorned.”12 The daughter of Herodias is used as a tool for her mother’s revenge against the Baptist. Herod so naive as to think Jesus was the resurrected Baptist and so rash as to make an open-ended promise to a charming little dancing girl. The story of the Baptist’s death, his head presented on a banquet platter—could it have been stuffed with an apple in the manner of roasted swine? No, Herod was a Jew of some sort after all13—all told in the past perfect, twice removed from the present—too awful to relate. A man who shouts “Repent!” must be thoroughly debased by those determined to stay their course.

And yet I feel for Herodias, hardly mistress of her fate, teaching her daughter the worst of feminine wiles as a matter of survival—for how was Herodias to have provided for herself and her daughter with their husband and father dead if Herod had obeyed the Baptist’s injunction against a purely figurative incest and repudiated her? Who would dare to have her and her child after that? All victims of a cosmic plotline in which the Baptist, who had given new life to so many, had by one device or another to die, in order to make way for Jesus. It is a wonder more people do not doubt the goodness of God on the basis of Scripture alone. Had the Bible been the work of one man, he would be considered a misanthrope.

Under the mattress with you; it is not safe to write so freely in such a heretical mood. If Mrs. H. were to find this and have someone translate it for her, I could be out on the street before my master or Emil would have a chance to intervene. Fortunately, I keep my own chamber and she is too proud to snoop.

June 9

Rain all day today. Helping in the kitchen. No skill, just the ability to take direction. A father cannot teach a girl how to cook, but he can habituate her to discipleship. Conversation in the kitchen is lively—a welcome relief from my relative isolation, though hardly edifying. Mostly gossip not worth relating. I enjoy watching the dog make itself comfortable by the stove—what a handsome and good-natured animal. Sometimes I think the true child of God is more like an animal than a human being in simply accepting the good that is at hand. My fingernails are still black from digging in the garden yesterday!

Matt 14:13–21. “And he had the people arrange themselves on the grass”—five thousand men, not counting the women and children, so five thousand families, really—an entire town, but not arranged as people arrange themselves, according to rank and wealth and language and livelihood, but in an order not known to us, of angels or animals, an invisible pattern, seemingly random, in which no one wonders where one belongs. The dog belongs beside the stove because that is where it is warm, that is all. He can feel the warmth—he does not have to see it. He does not have to ask after his food like the theologian who wants to know, why five loaves and two fishes precisely? He just eats and drinks and is satisfied. And yet it can be dangerous for a human being to be so simple-minded as to huddle with whatever warmth is offered. Not every man who offers what is needed in the moment is a son of God. How trite I have become in my disillusionment—how stupid!

June 10

My master told me a parable this morning—the story of three sons who loved their father so much that they gave up their lives for him, each in a different way. That was not what their father wanted for them, but they could not help it, he had so devoted himself to them. One gave up his life by trying to do everything right and going mad, another by running away and catching a fatal disease, the third by acquiring a name for himself that was not his own. But the saddest thing of all was that while they were living, the brothers could not abide one another, so intent was their focus on the father. And all died childless.

Matt 14:22–36. “O you little-believer, why do you doubt?”14 A little belief gets us into a lot of trouble. And so we sink before we can rise, because we are all littlebelievers at first. Even Peter, so full of himself—O Lord, let me do exactly as you are doing, whether it is walking on water or sitting with you at the right hand of the Father—sank like a stone.15

My master’s parable haunts me. He is too much like Peter, I fear, trying too hard to be the disciple who never disappoints, spurning established religion just as Jesus did, honoring the Father beyond all reason. More rain today.

June 11

Extremely damp and chilly today. Unpleasant outdoors, dark within. Even the gardener seems dispirited. Staying indoors by the fire I helped with the mending. I have learned so much in this household to make an honest woman—by that I mean a useful person—of myself. But my master’s influence, unlike that of his servants, takes me in a different direction—not exactly back to my childhood days spent in my father’s library with great curiosity but little sense of real purpose. No, with my master there is a sense of urgency, and not so much to know more as to be more. Book-learning is a paltry thing in comparison to—what? “Being” does not convey the quality, because we all in fact “are”—we exist, like it or not. But being—not exactly with a sense of purpose. Whatever it is, I feel it most in my master’s presence. Being with him I feel that being itself has new possibilities. And yet he barely takes note of my existence these days. He is mostly out on one of his infernal carriage rides,16 busy with his work, or sleeping off a night on the town.

Matt 15:1–20. “What goes into the mouth does not pollute the person, rather what comes out of the mouth pollutes the person . . . What comes out of the mouth, comes out of the heart.” A sinner knows what is in her heart and does not worry, therefore, about externals. Did Jesus really have such a grim view of humanity? He says nothing here about the good in people’s hearts. Maybe he does not want to get into a consideration of good and evil warring in people’s hearts; he just wants to keep the focus on the internal orientation of the conscious sinner, as opposed to the focus on externals which is typical of the unconscious sinner. Matthew must have been very angry at his own Jewish people who did not convert to Christianity. He makes it seem as though the non-Christian Jews have everything backward. I do not think Jesus could have hated his own people the way Matthew seems to. But then Jesus does say those who do not follow him are not his people. For a religious Jew, this statement is inconceivable. How angry was Jesus, I wonder.

June 12

More rain. Working my way through Faust (which I have read before but hardly remember) and finding Mephistopheles’ reputation for subtlety understated. Is he a mystic (“In the beginning was the void”), a Manichean, or merely evil? Merely evil seems the least profitable reading. Consider the following exchange with Faust.

Faust.

You call yourself a part, and yet you stand before me complete?

Mephistopheles.

The modest truth I tell you.

Though humanity, the little world of fools,

Ordinarily considers itself a totality;

I am a part of that part that in the beginning was everything,

A part of the darkness that gave birth to light,

The proud light, which henceforth Mother Night’s

Ancient rank and realm has troubled;

And yet it does not succeed, because however much it strives,

It remains imprisoned, stuck to bodies.17

Darkness prior to, superior to rebellious light—light shackled, like Prometheus on his rock, to form, while darkness, the void, floats free, unformed and uncreated. Is this darkness prior to creation not the very being of God, neither form nor formlessness, uncaptured by any concept, the inconceivable turbulence that so loudly confronted Job in his first silent and then discursive misery?

Faust’s response is essentially what my father taught me to call an ad hominem attack, blaming Mephistopheles for being too intellectual: “You cannot destroy anything on a large scale and so you begin on a small scale.” Faust, a doctor and professor of medieval medicine (he would have been a contemporary of Luther’s) is talking to and about himself. He wants no more of his suffocating study and small life-denying profession. Great irony here—no talk of medicine as healing, except that the good doctor is “healed” of his compulsion to acquire knowledge. What he wants is not knowledge but experience, the tiny bit that is “parceled out to the whole of humanity.” Parts and wholes again, but not exactly as Mephistopheles saw it.

Faust.

I will say to the moment: But stay a while! You are so beautiful!18

So much is said of Faust’s thirst for godlike knowledge (I too have repeated this silly error), but this is exactly wrong. Perhaps Eve has been similarly misread. It was experience she wanted, not a godlike knowledge, not a paradise with everything neatly labeled in Adam’s head, whose only claim to expertise was that he had arrived on the scene a few hours before she did. She wanted to experience the world as it had been given to Adam, before he “mastered” it.

Matt 15:21–29. The Canaanite woman cries out, “O Lord, you Son of David, have mercy on me! My daughter is plagued by a demon.” Jesus compares her, a gentile, to a little dog, and says the children’s food must not go to the dogs, but she reminds him that even the dogs are entitled to the table scraps.19 And so her daughter is healed “in that hour,” Scripture says, but I am thinking it was in that moment. A hint of sun.

June 13

One gets a glimpse of Genesis 8—the renewal of the world after the deluge—when after a week of steady rain, the sky is drained and the earth begins to dry out. People walk about with one another or their dogs and seem grateful simply not to have drowned, given up hope, or gone mad from the sheer grayness of everything. My master stayed in the last couple of days but still we do not see much of him. One encounter in the library—he asked me how my Faust was coming along, and I said nicely, thank you, but that I was getting a different impression reading it for the second time, that Faust was tired of books and wanted life. He seemed pleased to learn the play was not new to me—he knows a bit of my background from Emil, but not more than Emil saw fit to tell. My master said he would like to hear my impressions after I finish Part One. I asked why Part Two (which I have not read) is not included in the same volume as Part One, and he said that it was because it was written decades later and only published after Goethe’s death. It seems impossible to carry on a conversation in this house for more than five minutes without the topic of death coming up. Is this the life Jesus came to give us? But I should not be so critical. My master is a sensitive man who has given me a home, however frequent the reminders of its end. I should be grateful.

Matt 15:32–39. Why repeat the miracle of the loaves and the fishes with fewer people and more food? Matthew seems to be pulling things together from different sources, but then what are his sources and why are they not included in Scripture? Anyone who has ever been truly hungry (as I have been) understands why food is miraculous, no matter how much food or how many people. The wild ratios (and the repetition) drive home the point that we are all starving and that it is not necessary to live in that way, though, as my people are fond of saying, “A person gets used to anything.”20 Mrs. H. worries that my master’s appetite is not what it should be. He works long hours in his library and merely “grazes,” as she likes to say. She is quite maternal toward my master. It is possible she is a distant relation from the Jutland, as was my master’s mother, who was brought to this house presumably as a family favor. Such a large family at one time, and now just one brother and a handful of nieces and nephews. My master’s books are his children, I like to think, which puts me off the moroseness that the very walls of this house seem to breathe, not to mention the family name.21

June 15

I am grateful my master does not have real children, for if he did, I would be called upon to teach them. It was in my past life as a governess that my prospects for future happiness were ruined. If I were a man and could have had a choice in my profession, I would have chosen the ministry over teaching. But aside from marriage, which is the livelihood of most respectable women, the choices are few: a nurse, a governess, a prostitute. I became a governess and learned to play a variety of roles.

Matt 16:1–4. The Pharisees want a sign. Good and bad signs. Good and bad times. What is the sign of Jonah? His prophecy of the destruction of Ninevah? Its people and animals in sackcloth? The withered shrub? Or the storm that delivered him into the belly of the big fish (since all the talk here is of weather)? The story of Jonah, so short, so ridiculous, so deadly serious. I wonder if Jesus is not making fun of religious credulity itself, which cannot see what is in front of its nose while asking after the supernatural. This tendency to misread signs or to look in the wrong places for the truth is just as much a fault of the educated as the ignorant. I certainly misread the signs when I was a governess, and the being that was delivered into my belly did not come out alive. How awful to remember—impossible to forget. I am destined to make many more mistakes in this life, but that will not be one of them.

June 16

Is it a sin to use Scripture as a crutch merely to keep going, to survive? I have never heard a sermon on this and probably never will, as Christendom is complicitous in this crime of misuse of the Word. Life is good when I do not think on the past and unbearable when I do—mistakes and failures with years-long consequences overshadowing bright moments. John the Evangelist writes: “In him was life, and the life was the light of humanity. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not grasped it.”22 Scripture keeps me in the present and orients me toward the future on the basis of a summary recognition that my past is a morass best left behind, where my sins are forgotten not by me, but by God, who covers them over with his darkness, the darkness that precedes all sin, the darkness that gives birth to light. Yes, that gentle darkness is the feminine side of God, containing the potential for life within. God is in the pre—no, Jesus is in the present—no no, the Holy Spirit is in the present (the Spirit of Jesus)—Jesus is past (supplanting Satan, like Jacob supplanting Esau, though Esau did nothing wrong!) and future, and God comprehends all of it. Probably not sound Trinitarian doctrine—what would those fierce Dominicans have to say, those wolves in sheep’s clothing, though I think the sharp contrast of their black-on-white habit gives them away—but it matches my experience in this body.

What happens to the Holy Spirit after death, I wonder. It cannot be our lifeline to Jesus any longer—it seems it will not be necessary. Does Jesus stop having a spirit when there are no longer any bodies to get in the way? What kind of talk is this? This is why I need Scripture as a crutch—to keep from landing in a heap on the side of the road, lost in fruitless supposings, passed over by the priest, who hurries on to more important errands.23 But what I really wanted to express is the notion that the very same book, whether the Bible or Faust, can open one’s mind to reality one day and shut it down the next, depending on how one uses it. So its being a “crutch” is not the point so much. I am not clear on this—maybe another time.

Matt 16:5–12. The yeast of the Pharisees is false nourishment. When Jesus breaks bread with his followers, it is the same bread and yet different. The Pharisees do not bother to feed the multitudes (this is part of the problem—they are all talk and no action), but even if they did, it would be all wrong. So if books are like bread (Jesus says bread is a metaphor for teaching), the real issue is not so much the substance of the book (it must be a good book but even a good book can be offered in the wrong way), or how the followers are inclined to use it (this is usually mistaken as well), but how it is offered that matters. Jesus offers us bread, teaching, a crutch freely, and as soon as we realize the freeness—the grace—of that offering, the fact that we are using it as a crutch no longer matters. The crutch falls away at that moment of realization, and we find we can walk without it, though we keep it in a safe place (our hearts) so we can offer it to others when the time is right.

The need to write is a gift in two ways. It forces me to give my world back to myself and give to the world what I have found. It becomes an offering. My world is so small—a few people—a few books. But does this really matter? “Beware of the yeast of the Pharisees.” Leaven makes bread appear to be bigger than it really is. The size of one’s world is not determined by the number of one’s friends or the desirability of one’s attributes, but by the freeness of the offering.

June 18

I sound like a frustrated preacher. How pathetic! My master—how is it with all his education and wealth and the privileges and opportunities afforded him as a man, he is so at odds with everyone and everything? I have heard it said that younger sons have more trouble than older ones. What is (or was) it like to be the youngest of seven (four girls and three boys)? I would hardly know, an only female child and no mother to speak of. Mrs. H. has children of her own but does not draw comparisons. “Bless God, they live” is all she will say.

Matt 16:13–20. I am reminded of Faust’s complaint that anyone possessing truth and revealing it will be hounded to death, not by the truth but by liars. Jesus strongly warns his disciples not to reveal who he is. That is to protect them, to keep the real threat to himself for as long as possible. But once he is gone and they are sent out, there is no more safety. Or rather I should say the Holy Spirit protects the mind and heart, but not the body as we know it. The body is a great mystery. All the saints’ bodies are the rocks that make up our foundation. To rename Simon Peter is to predict his martyrdom. To confess is to seal one’s fate. No wonder there is so little genuine confession.24 For things to make sense, one need only look squarely at them. And then try not to look away.

June 19

Headache. Clouds, then sun, then wind, then rain, over and over. The dog pacing the kitchen, underfoot all day. Faust gives me life. A different Word.

June 20

Struck by the seriousness of the historical references in Goethe’s burlesque tavern scene25 to choosing a pope, Doctor Luther, and the devil afoot in Spain. Remembering the historical Faust lived 1480–1540 and the Faust of the drama is no longer young, so putting the action circa 1520, at the start of the Reformation—1000 years before that the fall of the secular Roman empire and 1000 years before that the first destruction of the Jerusalem temple and the first diaspora of the Jews, the Babylonian exile. Spain, a reference to Catholic suppression of dissent—expulsion of Jews and Muslims, the Inquisition—“choosing” a pope alludes to the ascendancy of the Holy Roman Empire over the Vatican. So Faust’s midlife “dark wood”26 is situated at a tipping point for humanity. There is a grim but honest humor in allowing the weight of the world to rest on the shoulders of one over-educated and lovesick man, like the fattened rat, who in the end succumbs to poison.27

Matt 16:21–28. Peter as Satan, the adversary. “What good is it to a person if he wins the whole world and his soul is harmed?”

June 22

Summer takes me back to my childhood in Berlin, though the weather here is wetter and colder. Like Faust I am no longer young but with an untapped reserve of passion—for what exactly I do not know. My admiration for my master is childlike, unpossessive. I have just enough learning to realize how far above mine is his. And yet he too is a child, a precocious playmate. He knows full well all that of which he has been deprived, while powerless to provide for himself. He mocks the worldly and laughs himself to exhaustion—no tears to wipe away.

Matt 17:1–13. Peter an eager young puppy. It occurs to me these disciples are all young men. Jesus tries to teach them something about steadfastness in the face of disappointment, but they are either full of silly ambitions, explaining away the inevitable, or belly down in the dirt with fear. They would rather believe anything than that their brilliant teacher’s career is about to come to a disgraceful close. Young people are made for beginnings, old for endings. The middle-aged “look before and after,” like Hamlet, who was older than his years. My master is younger and yet ancient. He seems almost primitive to me at times in his disregard for social niceties. But really I think he believes he is the ghost of Socrates, the supreme ironist, come back to haunt modern Western civilization, akin to Mephistopheles, though with the genuine piety of an ancient Athenian that a modern German almost certainly lacks. I know nothing about the Danes, though from reputation they enjoy having the upper hand. But then who does not? Is there a truly meek people anywhere on God’s good earth? Perhaps in the Far East or somewhere in Africa or the Andes, but not for long, once we Europeans have laid hands on them.

June 23

If only there were some discernible plotline to my life. I tried comic, then tragic. But now it seems one long denouement. People live by the stories they tell. I am all out of stories. My master told me another story today which seemed to be his and yet widely applicable—perhaps mythic. Maybe it was a dream. At any rate, a young man was walking at night in the woods near a large town and heard an alarm. Someone needed rescuing, but it was not clear whether the person in trouble was in the woods where the young man was walking or in the slightly distant city. Soon people were combing the woods with torches looking for a body—it was already too late to help. Then an old woman appeared. She knew where the body of the young woman who had called for help could be found. The young man looked down at his feet and there she lay, but she was not dead. She was only sleeping. He lifted her up and they walked out of the woods together in the opposite direction of the searching crowd. The old woman had disappeared. I think my master wonders what sort of future there is for him without his bride. I feel like the old woman who knows where to look for lost loves—who disappears the instant they are found.

Matt 17:14–21. Mental illness as evil spirits—exorcism as healing. The disciples ask, “Why were we unable to drive it out?” The suffering of casting oneself into fire and water—alternating extremes of mania and depression perhaps? Or more literally a predisposition to self-destructive behavior by whatever medium happens to be at hand. Here the obstacle is not littlebelief but rather unbelief. Here even a tiny grain of belief accomplishes the impossible, because a little belief will transform into bigbelief and move mountains.28 The difference is not quantitative but qualitative. And then this proviso: “But this kind clears away only by means of praying and fasting.” And yet there are so many ways to pray and so much one can do without, that this path is not so narrow as one might imagine. My master is a wealthy man who indulges himself in many ways and yet does without earthly love, for example.

June 24

A string of cloudy days slows me down so much that Mrs. H. wonders aloud what I am good for and sets me to polishing silver as a rebuke for my lack of cheerfulness. That is her primary virtue, despite her worries, which are personal as well as professional. An eccentric master keeps everyone guessing, and her grown children do preoccupy her at times, despite their absence. Everything is delivered with a smile and a laughing voice (only an occasional sigh), however, which helps to keep darker thoughts at bay.

Emil I hardly think to write about, he is such a fixture here. His loyalty is remarkable. I wonder if in recommending me to the household he thought I might serve his friend in a way that few servants are equipped to do. I do not know yet in what my service really consists, but it does seem that my place is secure, that my master, Mrs. H., Emil, and I form a unit, a family, if you will. My master, who will not marry, is not close with his brother, and yet comes from a large family, so his happiness depends on having family which he lacks. How is it that our happiness can depend on the very thing we lack? Can we be destined for unhappiness?

Matt 17:22–23. “And they became quite melancholy.” Jesus will be handed over to those who will kill him. (The disciples do not hear what Jesus says about resurrection because to them it has no meaning. It is gibberish.) The importance of hands: blessing, breaking, baptizing, betraying. The controversy over handwashing—keeping one’s hands clean as hypocrisy. What is important is not the state of one’s hands but what one does with them. Where would Jesus have come down on the “faith versus works” controversy? My master is at work on a book that may answer this question, or not, as he is more in love with questions than answers.

June 25

Mrs. H. said that on the evenings my master is out of the house I may play the piano and sing. I gave up singing some years ago and find I have lost my voice through lack of use, but perhaps with practice it will come back. My master is very fond of music, especially simple hymns and opera during the season, I am told. One of the most delightful things is to come upon him humming an aria to himself—he is too much of a perfectionist to sing aloud, knowing his voice is neither trained nor suited to performance. His true voice is his writing, in which everything is performance. Perhaps I should say “voices,” as I understand from Emil that my master adopts different personae in his writing and often publishes under the names of characters he has created without having actually fleshed them out. They are known to his readers only through their points of view, which are equally elusive. How does a person write in this way and not lose all sense of himself, I wonder? But then perhaps this is the goal. Most writers write to lose themselves, and then publish to gain it all back, but not my master. He truly wishes to be rid of himself, and not entirely in a holy way, I fear. But then he is godly enough not to do himself any actual physical harm. There is no law (either of God or man) against a kind of social suicide, however, in which one repeatedly tells people exactly what they do not wish to hear. Does this violate Paul’s precept against giving offense? While in prison for preaching the gospel, Paul wrote to his disciples at Philippi that he carried his shackles for Christ, as was well known and which had emboldened his brothers and sisters in Christ to speak God’s word without hesitation. Then the following: “Indeed some preach Christ on account of hatred and contentiousness, but others out of good intention. Those announce Christ out of a desire for strife . . . But these do it out of love, for they know that I lie here answering for the gospel.” Paul experiences Todeslust: “For Christ is my life, and death is my victory”—or is he simply persecuted as he once persecuted others and seeing death as the only way out? He answers this with: “I have a strong desire to leave and be with Christ.” It is not what he is trying to get away from, apparently, as he is quite used to and content with suffering for Christ—this is his rut, you might say. It is what he is going toward, his longing simply to be happy at Christ’s side. But it is necessary to go on living “for your sakes,” he writes.29

A key word for Paul is lauter:30 “that you remain pure and without offence,” “those who seek strife are not sincere.” To become holy is to remain genuine, and so Paul instructs the Philippians to avoid strife even in his absence: “so that you become holy, with fear and trembling,” as though God himself were present, which God is. “For it is God who brings about in you both the wish and the fulfillment of his pleasure. Do everything without grumbling or doubt so that you may be without flaw and genuine, God’s children, innocent among a corrupt and perverse generation.”

This emphasis on purity, a telltale sign of Paul’s former career as a law-enforcing Pharisee, is completely internalized in his Christian ministry. Which is more oppressive, I wonder? And yet his intentions are good. Clearly the Philippians are especially dear to him. If he could lay down a royal carpet to heaven for them, he would do so. But then Christ has already done that. So perhaps Paul’s problem is one of redundancy. All ministers, by virtue of their very ordination, are redundant, and redundancy is always oppressive. My master fights against this oppression, and though he wounds the oppressor, he does not give offense in the proper sense of setting up a stumbling block for sincere Christians.

June 26

Noticing birds much more lately—their personalities, some fierce, others meek, according to species, I assume. Back to Auerbach’s Cellar.31 Mephistopheles’ parody of the wedding at Cana has an effect opposite to the miracle: Mephisto demonstrates his power over the phenomenal world in order to raise doubt. Mephisto is urged on by the tavern regulars to turn wood into wine, which then becomes fire. Jesus reluctantly consents to perform his first public miracle, turning water into wine, at his mother’s insistence. If Mary had not been so insistent, when would Jesus have launched his career in wonderworking? Would he ever have engaged in such showmanship? Was it really necessary? Mephisto is quite passive, on the other hand. What is Goethe saying about evil? It seems clear to me he thinks its “power” is highly overrated—that evil consists in the ills we stupidly bring upon ourselves. Faust’s case is not comparable to the ordinary men in the tavern. (This demonstrates Goethe’s snobbery.) Ordinary people do not grow through their encounter with evil—their characters do not “develop”—whereas noble yet flawed men such as Faust (worthy subjects of tragedy in Aristotle’s view) go through all sorts of changes, ups and downs, or expansions and contractions, in response to “the yeast of the Pharisees,” that unreliable medium of false growth. Evil = the falsification of what is true and good. Augustine was right. It has no existence by itself—a mere parlor trick.

Matt 17:24–27. The king’s children do not pay a toll for entering his kingdom. Of course not! They get in for free, Jesus says. And yet the hungry mouths of the temple fundraisers must be filled. In a lovely reversal, the two-penny coin32 comes from the mouth of a fish that Peter (a fisherman) fetches up out of the Sea of Galilee: one penny for Jesus and one for Peter.

I cannot help but think of my master’s financial freedom in this regard. He came “duty-free” into his inheritance. As the youngest, he did not earn it in any sense other than perhaps in terms of the emotional toll his youth took on him. I gather from the little that Mrs. H. has said and the perpetual gloom that hangs over this house that he and his brothers were much shut up in the library or their bedrooms, the father as strict as a drill sergeant and protective as a mother hen, the suffocating combination blanketed over with an additional layer of religious guilt. That the daughters were shut up goes without saying; girls are thought to be suited to imprisonment, better able to adapt to the hothouse atmosphere. And yet, mysteriously, all his sisters are dead. This business of making children feel personally responsible for a sadistic crime committed by imperial overlords against an innocent man nearly two millennia ago makes my blood boil.

And the mother, a lively spirit in my estimation, yet a former servant, a poor relation, helpless to do anything about it. My dream comes back to me. I had a unique destiny (a pleonasm) that I was being kept from by people who were afraid of what I was or might become. Is this not true of each and every one of us? There is only one miracle necessary to make the whole of creation sacred, and that is life.

For you have my kidneys in your grasp; you governed me in my mother’s womb.

I thank you that I am wonderfully made; wonderful are your works, and my soul well knows it.

My bones were not concealed from you, as I was made in hiding, as I was formed below in the earth.

Your eyes saw me when I was not yet ready: and all the days were written in your book, those yet to be and of which there was none.33

Life must be made in hiding, for the world works against it.

June 27

This is one of those days—the sun is shining brightly and the dog rolled in another dog’s shit and it was my task to bathe him—when I see through my own talk to the angry little girl who lies beneath, fists clenched, jaw set, voice silenced, too angry to speak. Not at the dog certainly. I think they do this to feel safe, taking on the stench of a strange dog so as not to become its victim. Masking one’s own smell. Angry at my condition—such a small world I live in, when I love and long for the whole of it. If I were a more instinctive animal I would have learned this trick of rolling in another’s shit to protect myself. It is too late for me to learn. And too early for me to start over, to relinquish this “me” and begin again from “scratch,” as Mrs. H. would say. I cannot help feeling that the life I am leading is not the one I was meant to have. Life itself is precious, but this life seems petty. If there were some quiet, passive way to simply disappear, I would do it. Who would be harmed by it? Is it a sin to die when I have no other way out of my prison? I know it is a sin to commit violence against my body, which is not my own. But what if there is no one to claim it? To fade away, as Clarissa34 is famed for having done so virtuously at what should have been the hopeful age of eighteen. I am twice that. As far as harming others, my father has disowned me, I have no children or husband, and as a domestic I am eminently replaceable. There is no other work for me. This is not self-pity. This is an attempt to be mercilessly objective about my futureless state in a way I am sure men and women younger than myself and in better circumstances (real or imagined) have no difficulty being. The kindness of my master and the good will of his household are not enough to anchor me, I fear. They are inwardly indifferent, and I feel that. The only creature really attached to me is the dog, who loves to attend me on my walks.

Matt 18:1–11. Turn around and become like a child! See that not one of you despise these little ones! The other two greatest commandments of our Lord,35 reducing all pride and despair to nought.

June 29

The cellar cool and damp. Also dark. I work there quickly.

Matt 18:12–14. When I was small I used to hear this parable of the lost sheep and think the little lamb had not strayed (the one out of a hundred) but was hiding. The herd is not always safe, and our Lord knows that. The lamb who loves the Lord is not brought back into the herd but is singled out—no longer hidden but raised up onto the shoulders of God. John writes of this recognition: “I know mine and mine know me as my father knows me and I know the father.”36 There are two ways we know him, by his voice, and by his laying down his life for us. The thieves and robbers we must hide from, or at least not answer to, for they choke the life out of us. They not only rob and steal—they murder our souls with shame.

Auerbach’s wine cellar—a little glimpse of hell, all goodness turned on its head, and a foreshadowing (more immediately) of the very next scene, “The Witch’s Kitchen.” The men in the tavern, full of passion and lacking all wisdom (unlike Faust, who possesses both), resemble the monkeys who serve the witch, warming their paws in their mistress’s absence. Faust’s aversion to the witch—he prefers the devil to old women37 and their folk remedies. But the devil does not do his own dirty work. A youth potion takes time and patience to distill, Mephisto insists, and so Faust must deal with the pharmacologically gifted old woman whether he likes it or not. How interesting that the young woman in the mirror (Margarete) appears to Faust seductively stretched out. He is seeing her in the mirror of his destiny not as who she is, as yet an undefiled maiden, but rather as what she will become in response to him.38

June 30

I think my master’s ironical demeanor—a few remarks today about Mrs. H.’s housekeeping regimen seemed to poke fun—is intended to avoid falsehood, but also tends toward falsehood. Everyone plays the straight man to Mephistopheles, Goethe’s master ironist. The witch’s magic spells are no more nonsensical than the theological doctrine of the Trinity, according to Mephisto. And while, of course, Mephisto himself does not actually believe this (the ironist is never persuaded), he sets us to guessing. I would say he makes us think (rather than swallow mystifying contradictions whole), but that is not what he is after. As the witch chants:

The high power

Of knowledge,

Hidden from the whole world!

And the man who does not think,

To him it is given:

He has it effortlessly.

To the academically trained Faust this is all nonsense, and yet there is sense in it. It goes back to something the Lord says—not entirely clear which person of the Trinity this is supposed to represent, since Jesus was also there from the beginning—in the play’s “Prologue in Heaven”: “A person strays so long as he strives.”

God and Satan are so often on the same page, so to speak, while noble humanity (Faust) fumbles to find its place. The perspective of the ironist—rising above. The perspective of the contemplative—resting within. Those poor desert mystics, how did they keep from going to the devil?

Matt 18:15–20. Dare I tell my master that I think he errs in perching himself on his ironic height, that he cannot be happy there, that happiness matters, that God wants us to be happy? What do I know about God or happiness? But I feel he is mistaken. And to avoid the Christian community (“where two or three are gathered in my name, there I am in their midst”) on account of their subjection to benighted leaders is pure arrogance. It is so much easier to say we must confront one another in private first, than it is to do it. And yet if we can venture it, he is there to help, whereas he flees from all backbiting. How pious and preachy I have become. I must be truly unhappy. I think it best not to wait until my master makes another ironical remark to let him know how I feel about it, as that would seem like a small act of revenge. Daniel, the lions, the Christians—who more fierce? Who more afraid?

July 1

No sign of him today—working, sleeping, taking meals in his rooms or out. So elusive. Faust about to meet Margarete in the flesh for the first time. He will be her undoing. Knowing this already on a second reading—not learning through suffering (it is too late for that) but a heightened suffering through knowledge, seeing things for what they are. My new objectivity.

Matt 18:21–35. “Should you not have shown mercy to your fellow servant as I showed mercy to you?” The arithmetic of sin. Revenge-cycles expand eleven-fold through six generations. Cain avenged seven times, Lamech seventy-seven times.39 Mercy-cycles, to root out revenge, must expand 490-fold within one generation. Where does Peter get seven from? He must be thinking of the Sabbath and Jubilee cycles. People and the land are allowed to rest every seven days and seven years, and debts are forgiven and indentured servants released from their servitude every forty-nine years—seven times seven.40 To forgive “from the heart” is to cease keeping track. What long memories we have for sin, though I could not tell you what Mrs. H. and I served our master for dinner last week.

Faust is a very Christian play at heart, I think, for the only hint of revenge is in Mephisto’s sport with the vicious, and this is only momentary, and is only giving them not what they deserved, but rather what they desired, in the form of a literalized metaphor, e.g., “firewater” for the men in the tavern. Be careful what you wish for, Mephisto playfully warns again and again. He could just as well be a Brahmin or a Buddha, preaching on the ravages of passion. Real love, not the morose morality play of sermonizing sinners, is what Goethe will extract from Faust. But first he must become a full-fledged sinner. Faust must know a deeper regret than what he felt for his patients who suffered and died under his benighted medieval medical practice. But I get ahead of my reading.

July 2

A dream last night. I had my little girl—born alive—and she was five years old. We were walking hand-in-hand down the street—it seemed like Berlin, but with everyone speaking Danish and all the signs in yet another language. But my little girl and I spoke German. Her name was Mai, for the month in which she was born, and it was spring again and the city was fresh and very pretty. Mai popped the question, “Where is my daddy?” just like that, entirely out of the blue, and I said “in heaven,” without thinking. I did not mean to suggest that he was dead (he may or may not be, for all I know), but to indicate that her only hope for paternal protection would come from above. We walked on. In the dream I had no misgivings and thought I had been clear. When I awoke I remembered all my losses.

Matt 19:1–12. “Some are neutered because they were born that way, and some are neutered because people neutered them, and some are neutered because they neutered themselves for the sake of heaven.” Jesus tells his disciples that whatever he or Moses has said about marriage or divorce at any given time is meant strictly for the understanding and situation of those to whom each was speaking. But in this short disquisition, it seems to me, he has covered all the possibilities. He has provided an anatomy of marital dispositions. The natural state, he argues on the authority of Genesis, is for a man to be united with a woman for life. Moses allowed divorce, he claims, on account of the hard-heartedness (we would say heartlessness) of the ancient Israelite men toward their women. (They were polygamous, like the Arabs today, I gather, though this is no proof of insensibility.) But the most interesting cases are represented by Jesus himself, who I do believe was celibate for the sake of his ministry (who in his right mind would marry and have children knowing his fate would be that of Jesus?); Paul, who I think was not suited to marriage from birth, being of the most extreme temperament; and people such as myself, and perhaps my master, ruined for marriage by what others have made of them. Certainly combinations of these categories are also possible. Luther began with Jesus and ended with Adam. It is a wonder the monastery did not ruin him for marriage.

Faust meets Margarete “in passing” and, in response to his gentlemanly courtesy, she drily responds that she is neither pretty nor a young lady,41 by which she does not mean to suggest she is no longer a virgin, but rather that she is not overly given to undue courtesy. She proves her point by being so curt with Faust, who is not the least bit deterred—on the contrary, he is charmed by her rudeness. Or rather her rusticity.

July 4

My master asked me today if I believed in equality. I answered, “I believe we are all equal before God.” He said somewhat impatiently, “Yes, of course. But does that translate into political equality?” I was so amazed that he would put such a serious question to me with the expectation that I would have an immediate answer, which I felt I would be called upon to justify in the very next moment, that I simply stared at him. He stared back. Knowing full well what a wealthy man would want to hear from a servant, I hedged with, “Not in reality.” He mimicked my words back to me, “Not in reality,” punctuated with another question, “but which reality?” “There is only one reality, Sir, in which we proceed to become what God has known us to have been from the beginning, as Saint Paul put it, neither Greek nor Jew, free nor slave, male nor female—neither marrying nor given in marriage. We are free to become what we are, but we will never be equal until we are capable of regarding one another in the light of God’s countenance.” He seemed taken aback at that, whether on account of agreement or disagreement I could not say.

Matt 19:13–15. The disciples think children are a waste of their master’s time, but Jesus thinks they are the heart of the matter: “of such is the heavenly kingdom.” Margarete says she is not a young lady, not because she is ill-bred or immoral, but because she is still a young girl, a child. True innocence is before all distinctions—of such is the heavenly kingdom.

July 5

Mrs. H. and I into the cooking wine this evening. Consolation for a failed meal, one of her rare opportunities to prove her worth in the kitchen missed. Or did the wine precede the culinary disaster? Our master was very forgiving—perhaps he sensed the cause. I am certain he partakes when he is out, whereas we go nowhere but to the market to supply his needs (and I on my walks with the dog). Mrs. H. is a widow whose children do not visit. Our master has become her surrogate son, and she worries about him as she would her own if she knew more of their doings. “Out of sight, out of mind”—true even for a mother.

Surprised by my master’s question yesterday, even more than he was by my response. He is opposed to all social leveling, as far as I can tell, and yet he seems to value the opinion of a servant, or at least wants to hear it. Perhaps just taking the pulse of the people.

Matt 19:16–26. Jesus tells the rich young man, “If you want to be complete, go and sell what you have, and give it to the poor . . . When the young man heard this, he went away troubled, for he had many goods.” My master’s goods are many, and he values them greatly. Does this make him a hypocrite? Is my relative poverty necessarily a spiritual boon? Never mind how I came by my poverty, but to inherit one’s wealth as my master did seems so innocent. He has not devoted his education or adult life to the pursuit of wealth, but rather to understanding. I will not say knowledge or reputation, because these things are vexed and his approach to them has been sidelong. Better yet, he seeks wisdom. Solomon exhorts rulers to wisdom, for “a harsh judgment will be held over the powerful.”42 How odd my master conducts himself as a weak person when in fact he has so many advantages of which he makes full use and has no intention of giving up. Are these weaknesses of body, mind, or social standing—the burden of the family curse that has actually bent his back, the disadvantage of the younger son, the lack of a wife and children? Now that I consider the possibilities, I see there is no need to pose the question. He is weak in many ways, like a true apostle, “for when I am weak, then I am strong.”43 But is this true of those who are weak not by choice, but by necessity?

July 6

Paul refers to his affliction as his weakness—some disease, perhaps a family trait, not clear what it is, but not voluntary, in any case. So the matter of affliction has no relation to the choice of poverty, unless one thinks Christianity consists in willing God’s will, which cannot be escaped no matter what one chooses.

Matt 19:27–30. The one who abandons all of life’s goods for the sake of Jesus’ name will win “eternal life.” “The first will be last and the last will be first.” But what if the abandoning is not done by me, not chosen by me, but done to me? Do abandoned people make good disciples, or are they merely weak, worthless people trying to make something of themselves, trying to get over on other people by means of paradoxes and perverse principles? To abandon one’s children—is this what God wants? Always the dilemma of Abraham and Isaac. Who is this man Jesus, really, and why has he gotten so much attention? What makes him different from any other eccentric martyred for his lack of common sense, his lack of instinct for self-preservation? We are all sons and daughters of God.

Faust has found the little woman of his dreams by seeing her image in a mirror and sniffing around her virginal chamber. He has fallen in love with his idea of female purity so that he may become something other, better, than who he is. “Poor Faust, I no longer know you,” he says to himself while succumbing to the enchanting atmosphere of Margarete’s spotless, empty room.44

July 7

A warm and brilliant day. The dog is eager for a walk. Mrs. H. and I have gotten the rest of the carpets out to sun and air. There is so little traffic in the house, they hardly need beating, but there is the dust, some ash, and the dog hair, so we do that too while the weather is good. The light invades my senses, my mind—I can almost hear it, a buzz of liberated energy. I dreamt last night of flying, first with ease and then with some difficulty. As always there are people around and it is unclear whether they notice but I worry about their judgment. Are they ignoring me out of politeness, taking their time deciding how to respond, or waiting for me to fall? I love to follow the contours of the ground and treetops—there are never buildings to fly around, but sometimes I fly inside large rooms with high ceilings, always staying close to the ceiling when indoors. It would be nice if I could carry powers from one set of dreams over into another. Even a little capacity for flight would be so helpful in my dreams of impossible staircases. But what determines the plot of a dream is the self-imposed horizon of possibility in that dream. These horizons do not overcome one another—they are fixed. The gardener mows, steering clear of our carpets.

Matt 20:1–16. “Have I not power to do what I want with those who are mine?” Last first, first last. The application of the parable ends with “For many are called but few are chosen,” and yet in the parable itself the householder hires everyone he meets throughout the day, and even more improbably, at the exact same wage. It is the liberality, not the selectivity, of his hiring practices that offends his workers. I am grateful that no one in Master Kierkegaard’s vineyard is offended by what I receive despite my late arrival; I believe we all have his affection in addition to a livelihood and a home. The dog waits patiently. He appears to be asleep, but as soon as I move he will jump up. A great deal of light still left and the air mild.

July 9

Living in this, his house, like Margarete with her necklace, an illicit gift from Faust. “If only the earrings were mine!”45

Matt 20:17–19. No mention of the disciples’ reaction to Jesus’ third announcement of his Passion, unless the next passage is taken as continuous with this, in which case the response is not to deny or become sad (as with the first and second announcements), but to ask to share in his destiny. But is this possible? “Can you drink the cup I drink?”46 Jesus asks. Margarete sings a tragic drinking song in which a king takes his last drink from a golden goblet given him by his lover. He then throws the goblet into the sea and we are made to watch it sink—or drown. The giving and receiving of gifts, the acceptance of cups. The rather obvious grail imagery turned on its head. Margarete’s room befouled. Breathing in the stale, heavy air left behind by Mephistopheles and Faust, she breathes out this drinking song, an uncanny blend of innocence and experience. She longs for her mother.

July 10

Mephisto reports to Faust that Margarete’s pastor has appropriated her necklace with the following justification:

The Church has a strong stomach,

Has devoured whole countries

And never yet overeaten.

The Church alone, my dear Ladies,

Can digest ill-gotten gains.47

Faust is indifferent to the corrupting powers of church, state, commerce, and the devil, but is worried about Margarete, now his Gretchen, for along with her necklace she has lost her peace: she “knows neither what she wants nor should.” Mephistopheles is the first to use the nickname—the acknowledgment of her innocence comes as a farewell. She is no longer Margarete, intact, but a diminished version of herself.

Matt 20:29–34. Jesus and the two blind men at Jericho: “O Lord, Son of David, have mercy on us!” “What do you want that I should do for you?”48 They tell him they want their eyes opened, and at this request Jesus commiserates with them. They want to see what he sees and he alone knows what this will cost them. As soon as their eyes are opened they follow him, for what other way is open to them? Jericho—the place where the old structures fall away—Jesus the new Joshua. If the blind men had, like Faust and Gretchen, not known what they wanted, they would not have been able to ask for it, the prerequisite for receiving it. Faust thinks he knows; Gretchen knows she does not. Goethe has captured here something of the inescapable in male-female relations, though age is clearly a factor too in one’s self-confidence. Men lose it in middle age; women gain it. This is why Faust had to be made young again by the old woman in a process the ageless Mephistopheles could not facilitate. It takes time, the one thing Mephistopheles does not have.

July 11

Blue sky. One lonely cloud suspended, hardly moving, set like a misty gem in its brilliant background. Where was the sun? Behind me, I suppose. Warm and quiet.

Matt 21:1–10. Jesus enters Jerusalem. The praise of the people is in reality a cry for help, of which they are unaware. Hosanna! Save us! Is it the function of tradition, any tradition, religious or otherwise, to conceal our fragility from us, so that our most urgent, heartfelt pleas resound as honorific nonsense, so that we are no longer able to trace the origin of our most grievous disappointments? The highs and lows of honor. A hungry crowd. A tasty prophet.

I am ignorant of politics and yet not deaf to gossip, of which considerable chatter is given to movements of liberation, rebellion, revolution in the heart of Europe—what to call it depends on who is doing the talking, and who is listening. I feel safer here than in Berlin, where I imagine there is much intrigue. I myself am so dependent on the powers that be that I could hardly wish for radical change, despite my understanding that such dependency is the root of oppression. I like to think I am independent of mind and spirit, as Jesus called his disciples to be, but then there is also an economic aspect to the calling—even the poor and oppressed are bidden to sell what they have and give away the proceeds. One does not have to be a rich young man to balk at this. He was saddened by the good news—I am more likely to be angered. Have I not already given more than I should have to every man I have ever met? And what to show for it either spiritually or emotionally? What entitles the temple priest to the widow’s last farthing? Jesus never asked for money, and he never thought much of those who did. The sun is behind me. Warm and quiet. A single misty gem suspended in a brilliant blue sky. The ground is strewn with palms and psalms resound. There is no way out. Hosanna!

July 12

When I think of the evil things people have said to me and I realize how scarred I have been by them, I understand how important it is to refrain from negative judgment—all judgment if possible, but especially to keep one’s condemnation to oneself. My master is so kind to me and yet so insulting to his peers—even those who praise and support his work, those who would learn from him. There are those who find him perverse.

I am not well this evening. Perhaps it is the heat, or the topic, or something I ate. I need to drink more water to keep up with what I have lost—and the headache, since yesterday afternoon.

Matt 21:12–17. Jesus cleans house. Funny how the mind plays tricks when one is lightheaded. I read “house of prayer” as “house of begging.”49 Those not yet of age50 and infants are more likely to say something praiseworthy than those honored by ordination and academic status. Is it the training that turns men’s heads, or the honors, or both? Perhaps my master’s sharp words are justified. How is anyone seeking truth to second-guess what appears to him, upon careful observation and long reflection, to be true? Jesus, one assumes, took it all in in an instant. Looking and listening were one and the same with understanding. He did not have to visit the Jerusalem temple for five or ten or twenty years to get a feel for what was holy, what was corrupt, and what was reasonable human accommodation. My master has had his long loving look at the Christianity of Copenhagen and come away disenchanted, not with Christ, but with the international cartel that seeks to profit from his sacrifice. When I look such awful truths in the eye, oddly enough I am less angry about the mess men have made of religion, and simply very sad. And determined not to be fooled. Poor Margarete, a child in the hands of the devil—and Marthe, a married woman but none the wiser.51 I have a fever. I will lie down.

July 13