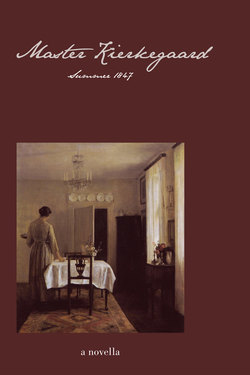

Читать книгу Master Kierkegaard: Summer 1847 - Ellen Brown - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Translator’s Preface

ОглавлениеTo my reader is owed an explanation of the circumstances under which the work at hand came to light. I have a fondness for used furniture and a constant need for more bookcases. So when I learned of the death of a colleague of mine at the seminary where we both had taught, and, subsequently, the sale of a few remaining household items not taken possession of by his heirs, a mixture of affection, curiosity, and opportunism impelled me to attend.

One bookcase in particular drew my interest. A simple, almost rickety affair—weakened by much moving about the country for fellowships and teaching posts, no doubt—it held itself together by a series of crosses. Not being a woodworker, I can only give a layman’s description of its construction. Each shelf had two tabs of wood projecting from each end, and these extended through holes cut in the side panels. Likewise, each tab had a hole cut in it, and through these, square dowels had been wedged, thus securing the side panels to the shelves. This simple but ingenious portable design was barely adequate to unify the structure of the whole—it had a tendency to lean to one side or the other—without its accustomed weight of books, nearly all of which had by this time been given away, sold, or thrown out.

A single volume remained, printed in the German script known as Fraktur, a rune-like font tiresome even to native German readers, but especially trying for those coming to the language later in life. Thus the little book lay pale and neglected on the bottom shelf. Most likely, the executor of my colleague’s estate (a nephew, I believe), intimidated by the mystery of its gothic typeface, had been reluctant to merely toss it into the dumpster. The appeal of Fraktur, commissioned by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian and banned during the Third Reich, faded altogether after the Second World War. It was still much in vogue in the nineteenth century, however, which is when this modest and decaying little book, cloth-bound and sewn, is likely to have been produced. No date is given by the publisher, a house in Berlin of no particular reputation engaged in publishing authors of similar stature. The author’s family name is also withheld.

What follows is an annotated translation of that volume, containing the journals of a woman of feeling and intellect. I will not forecast her circumstances, which are both affecting and instructive, as premature disclosure would weaken their influence upon the reader. To whom this solitary and thoughtful creature may be compared in the history of female writers is a speculation I will not venture upon. Perhaps Kierkegaard himself overstated the case when he wrote that “all comparison injures. Yes, it is evil,”2 but one senses he was not far from the truth.

I would just add that our author was evidently a student of theology—informally, of course—in her own right, being an attentive reader of the Gospels as conveyed by Martin Luther. Not having access to the same editions against which to compare and correct her extracts and paraphrases, I have translated them as she gave them to us, which is, I like to think, doing justice to her, who had made them her own.

Evagrius Brooks, Th.D.

Princeton, New Jersey