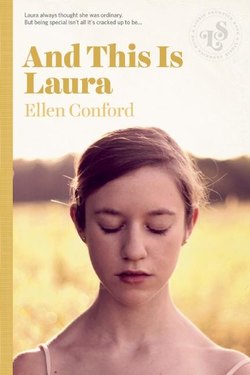

Читать книгу And This Is Laura - Ellen Conford - Страница 8

ОглавлениеJUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL is no big deal.

Back in the sixth grade they kept telling us how different things were going to be once we got into Junior High, and how we would be expected to act mature and be responsible and self-disciplined, but so far the only thing they were right about was when they told us there would be a lot more work.

The teachers keep saying we’re supposed to act like young adults but they keep treating us as if we were still in sixth grade. We move around from class to class instead of staying in one teacher’s room for most of the day, but then, in elementary school we went to different teachers for things like Art and Music and Gym and Library. The only big difference is that in Junior High you have hardly any time between classes, because they allow three minutes to get from one class to the next, and unless you have roller skates and a perfectly clear hallway, it is physically impossible to make it from one end of that building to the other in three minutes. And you couldn’t roller-skate up two flights of stairs, anyway.

This particular day I was sitting in French class waiting for the teacher to arrive. The bell had rung already, and he was late. (I guess he forgot his roller skates.) It was the last class of the day and by the time I got to it I was pretty well up to here with school and feeling more like a caged panther than an enthusiastic learner.

As I sat there wishing for a bomb scare so they would have to clear us out of the school in no time flat and send us home, Beth Traub leaned over and asked, “Are you going to join the dramatics club?”

Beth was also in my English class, but I hardly knew her. We hadn’t gone to the same elementary school. There are four elementary schools in our district but we all go to one junior high, which means that I didn’t know about three-fourths of the kids in the seventh grade.

“Yeah, I guess I will.” By this time the thought of staying in school an extra forty-five minutes, even for a club, didn’t thrill me, but I had announced to everyone that morning that I was going to, so I felt sort of trapped.

“I am too,” said Beth. “I’ll meet you after homeroom, okay?”

“Okay. What room are you in?”

“108. What room are you in?”

“114.”

“Wait for me, will you?”

“Sure.”

Our teacher hurried into the classroom, panting slightly.

“Bonjour, mes élèves.”

“Bonjour, Monsieur Krupkin.”

“Ouvrez vos livres à la page quatorze, s’il vous plaît.”

He wrote “p. 14” on the board, because we were just beginning to learn numbers and hadn’t gotten past dix (10) yet. Mr. Krupkin tried to speak only French in class and sometimes it got kind of confusing. After all, how much French could we understand after three weeks?

The period dragged by. We took turns reading aloud the parts of Pierre and Juliette, who go to école supérieure every day, where they étudient such subjects as la géographie, l’histoire, l’anglais, etc. After école they come home and have a glass of lait and some petits gâteaux. Then they do their devoirs. On Sundays they go for walks dans le parc.

It sounded like a very dull life.

I waited for Beth outside my homeroom. She got there a couple of minutes after the dismissal bell, staggering under a load of books, an instrument case and a gym suit half-stuffed in a brown lunch bag.

“They ought to give us wheelbarrows,” she grumbled, “along with lockers. I don’t know how they expect us to carry all this stuff.”

“Do you think they even care?”

“No. No, of course they don’t care.”

There were about thirty kids in Mr. Kane’s room when we got there. Twenty-eight of them were girls.

Mr. Kane surveyed the group and smiled.

“Welcome to the Hillside Junior High School Drama Club,” he said. “I’m delighted to see so many budding young thespians with us. I’m sure we’re all going to have a lot of fun in this club as we learn some of the rudiments of acting. For those of you who are new to the club I want to tell you that we put on two plays a year so you’ll have a good opportunity to develop your talent in front of live audiences. What I thought we’d do today is a little improvisational pantomime. Pantomime is acting without words; you use movement and action to convey what you’re doing or feeling to the audience. We’ll do simple, everyday things you’ve done all your lives, but you’ll use no props, no words, just your imagination. Who wants to start?”

There was some foot shuffling and a few nervous titters, but no one volunteered. We certainly were a shy group, considering that we should have been eager to get up in front of an audience and act our hearts out.

Finally Mr. Kane said, “Why don’t we have one of our old members start off, so you’ll have an idea of what I’m talking about? Jean, would you? And let’s introduce ourselves as we perform.”

A plump, very pretty girl with light brown hair walked to the front of the room. She didn’t look nervous at all. She looked perfectly at ease in front of twenty-nine pairs of eyes.

“I’m Jean Freeman,” she announced.

“Jean played the lead in Sweet Sixteen last year,” Mr. Kane said. “Jean, why don’t you do brushing your teeth?”

She nodded.

Facing us, she took an imaginary toothbrush out of its holder and stuck it in her mouth. She held it there, her mouth slightly open, while she picked up an invisible tube of toothpaste and twisted off the cap with two fingers. She took the brush out of her mouth and squeezed toothpaste on it. Then she put the tube down on the side of the “sink” and reached for the water faucet.

It was amazing. Her movements were so realistic you could almost see the water running and the toothbrush in her hand. She put the brush under the water a couple of times and even examined her teeth in the mirror above the sink as she brushed them. She rinsed off the brush and stuck it back in the holder, then turned off the water. She peered into the “mirror,” baring her upper lip and running her tongue over her teeth. She even picked at the spaces between two teeth with her fingernail, as if she’d missed something. Then she gave a little satisfied nod of her head, capped the toothpaste and put it back on the side of the sink.

“That’s it,” she said, and broke the silence.

Everyone burst into applause.

Jean walked back to her seat and Beth whispered, “Isn’t that something? I could almost hear the brushing noise.”

“Me too. She’s really good.”

“Thank you, Jean,” said Mr. Kane. “Now that you have an idea of what you can do with pantomime, who else would like to try?”

Jean must have inspired us. This time quite a few people waved their hands to be called on, and even I felt the urge to try a pantomime. It looked like fun.

The next person was a short girl with dark, curly hair.

“I’m Rita Lovett,” she said, almost in a squeak.

Mr. Kane had her put on shoes and socks. She wasn’t nearly as good as Jean Freeman had been. In fact, if I didn’t know she was supposed to be putting on shoes and socks, I would have thought she was tromping on ants and spraining her ankles because all she really did was raise and lower her feet a couple of times and kind of hold her hands on them.

Beth looked at me and shrugged, ever so slightly, as if to say, “Either one of us could do better than that.”

I nodded to show I agreed.

“That’s not bad, Rita,” Mr. Kane said. “But remember when you do pantomime there are lots of little details that make it realistic and if you leave them out it’s not as effective. Can anyone suggest something that Rita might have done even before she started to put on her socks?”

What was she supposed to have done before putting the socks on? I couldn’t imagine. It seemed to me that Rita’s problem was mainly that when she was supposed to look like she was putting on socks she actually looked like she was stomping on bugs, but apparently that wasn’t what bothered Mr. Kane.

“She should have gotten the socks from the drawer,” said Jean from the back of the room. “And then she should have unfolded them, or unrolled them or something like that.”

“Right. You remember, Jean didn’t start right off brushing her teeth. She did all the preliminary things you do first, uncapping the toothpaste, turning on the water. It’s those little details that help your audience really see the thing you’re acting out.”

Beth and I both raised our hands. He called on me.

I went to the front of the room and looked back at all those faces. Beth smiled encouragingly at me. I tried not to show that I was nervous.

“I’m Laura Hoffman.”

“Laura’s sister, Jill,” Mr. Kane said, “was in this club a few years ago. She had exceptional talent. It seems to run in the family.”

I sighed. I wished Mr. Kane wouldn’t make such snap judgments. After all he hadn’t even seen me act yet and now that he had everyone expecting I’d be as good as my incredibly talented sister, I felt more self-conscious than ever.

Everyone waited for me to do something terrific.

“Make a peanut butter sandwich,” Mr. Kane said.

Peanut butter sandwich. Why, I’d done that hundreds of times. I reached for a jar of peanut butter above my head, like I was getting it from a kitchen cabinet. But I couldn’t really feel it in my hand. How big was the jar? How wide did my fingers spread when I held a real jar of peanut butter?

I got the bread and put it down next to the peanut butter. I held it in two hands, although I was pretty sure that wasn’t the way I usually carried bread around. Again, with the knife, I couldn’t “feel” how I would ordinarily hold a knife. Did I just clutch it, or did my index finger extend over the handle?

I stuck the knife into the peanut butter jar and pulled it straight out. I think I did the spreading part pretty well, like I was really smearing on peanut butter. But apart from that, I knew I wasn’t much good.

It felt so strange. I mean, even though all those people were watching me, what bothered me most was that I couldn’t remember how it felt to hold a jar or a knife, things I did every day. It was mystifying that a peanut butter sandwich was so much more complicated to make in pantomime than it was in real life.

“Not bad, Laura.” Was it my imagination, or did he actually sound disappointed?

A little let down, I went back to my seat.

“Did anyone notice anything Laura forgot to do when she made her sandwich?”

Rita Lovett waved her hand. Without waiting to be called on she blurted, “She forgot to take the lid off the jar!”

She smiled triumphantly, as if she’d somehow made up for not unrolling her socks by noticing my jar lid.

Beth looked disgusted. “She just couldn’t wait,” she whispered, “to pick on someone else’s tiny mistake. I thought you were very good.”

I was grateful for her sympathy. But I was so annoyed with myself! How could I forget a dumb thing like the jar lid, when I’d been so careful to look out for just those little details Mr. Kane warned us about? I remembered to put stuff back in the cabinet—I even put the knife in the sink, although probably no one knew what I was doing. I guess I’d been so busy looking out for all the little details that I forgot to watch out for the big ones.

Beth was next. She had to make a telephone call. Without talking aloud, of course.

She was good. She moved her lips and made faces and reacted like she was really having a conversation with someone. You could even see her leaning against a wall that wasn’t there and fiddling with the curly telephone cord.

I made little clapping motions as she came back to the seat, and she grinned.

No one could find anything wrong with her pantomime.

“That’s all we have time for today,” Mr. Kane said. There were a few groans of disappointment from some of the people who still had their hands up.

“We’ll do some more next week,” he promised. “And I’ll have some monologues prepared for you to read too. And after that, we’ll begin to talk about our first play of the season.”

The room buzzed with excitement. A lot of the shyness had apparently been overcome.

“And maybe,” Mr. Kane went on, “you boys could get some of your friends to come down and join us. We’ll need some male actors for our productions, you know.”

The boys didn’t say anything. They looked slightly uncomfortable. They hadn’t done any pantomimes or even raised their hands during the whole meeting. I wondered if they’d stumbled into the wrong room by mistake and had been too embarrassed to just get up and walk out. One of them looked really young, like a fifth grader, and the other was tall and skinny with stuck-out ears. Neither of them looked like a potential leading man.

“You were so good,” I told Beth as we walked out of the building.

“Oh, it’s just that he gave me such an easy one to do. Yours was much harder than mine. Try it, you’ll see how simple it is.”

“I will when I get home.” In fact, that’s just what I’d been planning to do. She’d made it look like fun to make an imaginary telephone call and I couldn’t wait to try it in front of a mirror.

Beth and I certainly seemed to be on the same wavelength. Though I hardly knew her, I did know right away that I liked her and wanted to get to know her better.

“Where do you live?” she asked. “Do you get the bus?”

“No, I walk. You know where Woodbine Way is?”

Beth shook her head.

“In Old Hillside Gardens.”

“Oh, sure, I know where that is.” She nodded.

Old Hillside Gardens is an area of Hillside with big, old houses, no sidewalks and lots of tall trees and broad lawns. They call it Old because right near it they built New Hillside Gardens, which has big modern houses, smaller, younger trees and sidewalks.

“We’re in Country Manor,” Beth said. “I have to get the late bus.”

Country Manor is a lot like New Hillside Gardens but newer and way over on the other side of town.

“Hey, why don’t you come home with me?” she said. “They don’t care who gets on the late bus. They don’t even check the bus passes.”

I hesitated. I wanted to, but it was already late and I had so much homework to do and I didn’t know how I was going to get home.

“Come on,” she urged, starting to walk toward the waiting bus. “We can do our homework together, and my mother could drive you home. Or you could stay and have dinner with us.”

“Well . . .”

“Come on, we’ll miss the bus.”

“Well, if you’re sure your mother wouldn’t mind—”

“Of course she wouldn’t mind. She’s always telling me to bring my friends home.”

Beth already thought of me as her friend. I liked that.

“And if we get our homework done fast,” she went on, “we can think up pantomimes for each other to do.”

“Or,” I said, following her onto the bus, “we could do one the other person has to guess. To see how realistic we can be.”

“That’s a good idea. Like charades.”

The bus pulled away just as we got into seats.

“Oh,” I said suddenly.

“What?”

“I guess I accept your invitation.”

Beth laughed.