Читать книгу Force and Fraud - Ellen Davitt - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеBY

DR LUCY SUSSEX

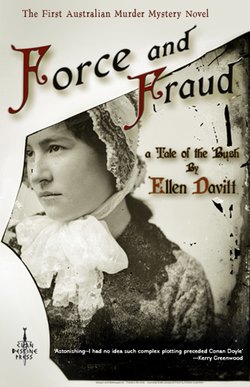

Ellen Davitt’s 1865 Force and Fraud was the first murder mystery novel published in Australia. It appeared in a popular fiction magazine, the Australian Journal, but its significance was not realised for over a century. Ellen and her husband Arthur were remembered as pioneer educationalists, the couple having been in charge of the Model School in Melbourne during the 1850s. They gained an entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, though with three major omissions: that Ellen was a writer, an exhibited artist, and sister-in-law of the famous Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope.1

Trollope has attracted various biographers; but his connection with Ellen Davitt was only discovered in the 1990s by education historian Marjorie Theobald. An earlier historian, J. Alex Allan, in his The Old Model School, described Ellen as having ‘overbearing self-esteem’.

Victor Crittenden – whose Mulini Press reprinted Force and Fraud in paperback in 1993 – commented: “Just imagine a woman in the 1850s daring to have a high opinion of herself and her capabilities”.2

Ellen Davitt was an unusual woman indeed. She was the eldest of five daughters, born to Edward and Martha Heseltine, a couple who were first cousins. The Heseltines married in London, in June 1810, when Edward was a bank clerk in Hull, Yorkshire. Ellen’s exact birthdate is unknown but she was baptised at Holy Trinity, Hull, on 4 March 1812.3

The family were then Anglicans; although by 1821, when their fourth daughter Rose (afterwards Trollope) was baptised, they had joined the dissenting Unitarian sect. Rose – as befitted the wife of a novelist whose Barchester series epitomises nineteenth-century Anglicanism – conformed to the Church of England upon marriage. Ellen went further, becoming a Roman Catholic; something which may explain her near disappearance from the family records.

Edward Heseltine was the son of a clerk, but got promoted to bank manager in Rotherham, then a market town near Sheffield. In character he could be hair-raising; as a young clerk he protested being kept late at work with exploding candles, something that could have got him sacked. His obituary notes other pranks:

During the panic of 1825 an old woman in the crowd of applicants for gold at the bank counter became very noisy. Mr Heseltine looked pleasantly at her, and said, “Hold your tongue, my good woman, we are preparing sovereigns as quickly as possible.” He had ordered a quantity to be made extremely hot. These he shot from a shovel in the old woman’s hands: down they fell on the floor. He then desired others to step forward for change; but the fever was abated by this application of heat, on the principle of homeopathy, “Like cures like”. A little time was gained by this expedient, and more substantial aid was procured.4

Martha Heseltine’s obituary listed little more than her virtues, and that her death (in late 1841) was due to injuries received in a railway accident the year before. The early years of the railway industry were hazardous. Various press accounts of this particular accident appeared, with the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent reporting the carriage in which Martha travelled derailed and turned nearly upside down. One passenger was thrown out the window and killed instantly; the others clung desperately to their seats. All were injured, including the Heseltine parents, and Miss Heseltine. Two and possibly three of the daughters had wed by this time; so if Ellen was still single she might have been present.5

Edward Heseltine remarried a year later, to Charlotte Platts. She was a daughter of the Unitarian divine and author John Platts, and younger than Ellen. This May and December marriage produced two sons.

In 1852, when Heseltine retired, aged 72, it emerged that he had helped himself to the bank’s funds. He had expensive tastes, being a dandy, and collector of art and armour. Trollope biographer Victoria Glendinning surmises he speculated on the railroads. Heseltine was a director of a small railway company, launched in 1836, the year he became bank manager. He subscribed for 20 shares at £25 each; a total expenditure of £500. Nobody seems to have enquired how he found the money; and he went on to embezzle at least £5,000, then a huge sum. For some time Heseltine played cat and mouse with the bank investigators, flitting around England whilst pleading ill-health and mental incapacity. Finally he fled to France, where he died at Le Havre in 1855. Fraud, if not force, was thus something Ellen knew from family experience.6

Ellen grew up in a family without sons, which belonged to a sect with a high regard for the intellect. She might have received a better education than most girls of her era; certainly the family valued reading, and Edward was on the committee of the Rotherham Book Society.

In an 1874 letter Ellen described herself as ‘a lady both by birth and education’ – a dubious claim, since a bank manager’s daughter was respectable rather than genteel. Additionally a lady was not expected to work for her living – as Ellen did. She wrote, on an application form of the same year, that she had:

Studied under Masters in England, spent some time in fashionable schools in Paris. The Sacre Coeur was one of them. Might have taken out a Diploma but for circumstances that prevented a longer stay in Paris [...], have [illegible] honours in History, Modern Languages, Composition and Elocution.7

Some degree of reinvention, common when people emigrated to the colonies, leaving a lowly or scandalous past behind, can be surmised here. The letter implies a French education; unlikely for a Yorkshire girl whose father, during her schooldays, was only a bank clerk.

Rotherham, where the Heseltines lived above the bank, was where most of the daughters married, including Rose, to the young Anthony Trollope. Here also Ellen may have wed. On 8 February 1836, an Ellen Heseltine married William Ashmoor. That a market town of 20,000 people could have contained two marriageable girls of that name is not impossible, but it seems unlikely.

Ashmoor, with the alternate spelling of Ashmore, was a name not uncommon in Yorkshire. Three separate William Ashmores appear in contemporary coverage in the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent. One was an old man, another a working-class villain; so the most likely candidate is an Optician, who went bankrupt in 1838.

Intriguingly, a Mrs Ellen Ashmore appeared in a Rotherham court case of September 1842. She was witness to a burglary, in which three women confronted an intruder who was armed with a poker. He struck at Ellen Ashmore, but missed. If this woman later became Ellen Davitt, then she was feisty even when young; and the realistic court scenes of Force and Fraud had a basis in experience.8

The British Census of 1841 (taken in June) provides a vignette of the Heseltine family in Rotherham: the dying Martha surrounded by her three youngest daughters, Rose, Isabella, and Mary Jane, who was married to Heseltine’s clerk Robert Edgar, with a baby. Another married daughter lived in Manchester.

Ellen is nowhere to be found; so was either out of the country, or for some reason not included in the census. William Ashmore the Optician does not appear in the census either. He would die, in May 1849, at the age of 57. If he left a young widow, she was free to marry again.9

Arthur Davitt’s death certificate states he and Ellen married c. 1847, in Jersey. That may not be accurate, as she was not the informant; and the certificate contains mistakes, giving Ellen Frenchified Christian names (Marie Hélène), and a Dublin birthplace. It was Arthur who was Irish, b. 1808, and an educationalist. It is possible he met Ellen in Kingston, outside Dublin, where the Heseltines holidayed; and where Rose met Anthony Trollope, then a post office clerk.

Arthur Davitt was a Professor of Modern Languages at the Sorbonne in Paris. If he took Ellen back to France with him, that is when she gained her school experience, but as a teacher rather than pupil. After returning to Ireland in the late 1840s, Arthur Davitt became an Inspector of Schools. Ellen taught drawing in the Irish National Board’s Model School for Girls in Dublin from 1851-4. During an 1853 visit by Albert and Queen Victoria, her ‘fine’ copy of Winterhalter’s portrait of the monarch in coronation robes, hung prominently in the school.10

The couple were childless; a factor in their next career move, to Australia. In 1853 the Commissioners of National Education in Melbourne wrote to the Irish National Schools Board, requesting they recommend a Principal and Superintendent for the new Model School in East Melbourne; preferably a married couple without family. In effect, thus were two positions filled for the price of one; for the joint salary offered was £1,000 – £600 for the Principal and £400 for his wife. The Irish authorities recommended the Davitts.

At around this time Edward Heseltine’s frauds were discovered; prompting another good reason for a trip to the Antipodes, lest the Davitts be tainted by scandal. Another factor was that Arthur Davitt had tuberculosis, for which a standard treatment was sea air and a warmer climate.

The journey proved eventful. The Davitts had to change vessels, since the steamship Great Britain soon developed engine trouble. They took the clipper Lightning instead, whose captain was James Nicoll Forbes, a man intent on breaking sailing speed records. During the Davitts’ voyage he nearly wrecked the Lightning on the desolate Kerguelen Isles. The incident is recorded in the surviving journals of the passengers; and also in Force and Fraud, Davitt’s account being so detailed that it suggests she kept a travel diary.11

If she had, it would have been interesting to read her version of a dispute on the ship, noted by passenger John Warren Whitings:

This evening we had by way of amusement to some of the passengers as they must have something to pass a way the time, a fight between two men cabin [first-class] passengers, I call them men because I cannot call them Gentlemen with any truth and justice to that title, Mr. Davitt and a Mr. Robinson. Mr. D. called Mr. R. a liar and pulled his ears also promised him a good kicking. A Mr. Swift wanted very much Mr. R. to fight Mr. D. at 12 paces with pistols. I offered the loan of a case but Mr. R. said he could not think of risking his valuable person in a fight with such a man as Mr. D. it lasted about an hour and caused great fun to some of us.12

The Model School would have seemed a plum position, but it proved fraught. During the 1850s education in Victoria comprised two systems: religious schools controlled by the Denominational Board; and the secular National Board of Education, which hired the Davitts. The two boards were bitter rivals, with the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches in particular opposed to non-denominational schooling. The churches, in turn, were supported by powerful Parliamentarians.

In order to prove its superiority, the National Board determined to build a Model School. The building, in East Melbourne, was to be as impressive as the new system of schooling; instead, it proved vainglorious and costly. The Model School may have looked imposing, but it was jerrybuilt, with leaks and faults evident even before completion.

In addition, the place was an administrative nightmare. Arthur Davitt was expected to run an Infant school, separate schools for boys and girls and a Teacher’s training college in the one building. In order to conform to Victorian notions of propriety, the male and female students, whether teenage or adult, as in the case of the teacher trainees, had to be kept strictly segregated. Moreover, the National Board of Education was under the same roof, and the real power in the School.

In the Victorian world-view, the male dominated the public sphere, the woman the private and domestic. Ellen Davitt transgressed these boundaries. She was a woman prominent in public life; as Superintendent she was in control of all the female pupils in the school. The position was subordinate to her husband the Principal, but the Davitts were a team. Arthur’s letters to the Board frequently included the phrase: Mrs Davitt and myself. Thus, while Ellen was a loyal wife, she was not in the background. She had opinions and was ready to express them, for instance suggesting changes to the School’s architectural plans.13

The Education bureaucrats, used to a female ideal of submissive modesty, would have found her challenging and threatening. Certainly J. Alex Allan thought her ‘the power behind the throne’; harsh, priggish, and fond of fault-finding. Her only merit was ‘efficiency’.14

The Model School generated reams of correspondence, preserved in the Public Record Office. Any disputes among the school staff – and some of them were over matters as petty as 4lbs of butter (which Ellen Davitt was alleged to have appropriated) – had to be referred to the Board, in writing. The result was an endless stream of crotchety correspondence.

A re-examination of these documents does not support Allan’s depiction of Ellen Davitt. Was he influenced by other sources, such as a former Model school pupil, who recalled that Ellen ‘copied Queen Victoria in her style of dressing and deportment, wearing a shawl, folded cornerwise, around her shoulders’. Certainly a woman who was not amused appears in his account of John Donaghy, a Master who broke the rules by fraternising with the female trainees.

Allan wrote: “One can fancy the shocked prostration of Mrs. Davitt when the Matron, Mrs. Berkeley – who also acted as duenna to the lady trainees – flew to her with the news.”

The comment is fanciful indeed, for there is no surviving evidence of what Ellen Davitt thought and did on the occasion. Her husband, though, felt that the Matron was “giving this matter more importance than it deserves”. We can deduce that Ellen agreed with him, for the archives show the Davitts supported each other unconditionally.15

What it reveals about Martha Berkeley begs the question why Allan singled out Ellen Davitt for censure. The Matron reported to the Board, repeatedly complaining of ‘disrespect’ (as Allan claims Ellen did) from trainees and servants. It seemed that she could handle neither, requesting that talk between the two groups be forbidden; “such a practice tending to subvert all order”. The prohibition was enforced, against the Davitts’ wishes. In fact so many of Mrs Berkeley’s requests were granted, that she seems to have had the ear of Board.16

One student reported that the Matron described Mrs Davitt as “fit only for an actress”. Ellen Davitt could be theatrical. It is recalled that when “she appeared at the door of one of the girls’ class-rooms, all work ceased and the class rose and stood in awed silence till she had ‘sailed’ majestically through the farther door”.

Berkeley was herself disrespectful here, for ‘actress’ was virtually synonymous with whore. Yet the regal Mrs Davitt could also be friendly. A group of female trainees spent three evenings in her apartment; on the third evening exiting in such high spirits that the Matron indignantly reported their “complete insubordination” to the Board.17

History (and herstory) can be a series of competing biases, rather than absolute truths. Allan makes errors, as when he described Ellen as coming from an old St Heliers family. In the archives, Martha Berkeley seems more contentious, as is Arthur Davitt himself. The Principal complained, for instance, that his deputy, Patrick Whyte, had grossly insulted him by leaving the ‘Esquire’ off Davitt’s name on an envelope; thus implying that the Principal was no gentleman. Whyte retorted: “in all my experience I have never been associated with a man with whom it is so difficult to act harmoniously”.18

Davitt was undoubtedly difficult, but he was also dying – in an environment that would have driven a healthy man to distraction. Relations with the Board, and with staff, steadily deteriorated throughout the late 1850s. It was at this point that the political climate of Victoria changed, with the goldfields boom time declining to a recession. The supporters of the Denominational system in the name of cost-cutting slashed the budget of the National Board of Education.

There were thus insufficient funds to run the Model School in the style to which it had been accustomed. The Board chose to abolish teacher training at the school and also the positions of the Davitts. They were given the option of continuing at the school for one final year, at reduced salary, or being discharged with the sum of £500. The couple chose the latter, although they felt a proper compensation would have been double that amount.19

Ellen Davitt’s response to the dismissal was energetic and combatant. She signed the discharge form under protest, asserting her ‘right of appeal to another and a higher tribunal’. The retort was sent from Granite Terrace, Carlton Gardens; where she opened, several months after the dismissal, the grandly titled Ladies’ Institute of Victoria. This school was advertised in Melbourne papers of 1859, as open for boarders and day pupils, and also offering evening classes, and training for governesses.

Girls’ schools might have been Ellen’s employment, but she could also poke fun at them. A character in her novel The Wreck of the Atalanta complained that a Ladies Seminary meant: “Weak tea, and bread and butter, and girls in short frocks making curtsies when they enter the room, and a piano always stunning one to death.”20

The private education market in Melbourne was highly competitive, and similar establishments included the Ladies’ College, run by Mr and Mrs Vieusseux. Ellen Davitt and Julie Vieusseux had coincided before, in the world of art. In 1857, both had work hung in the Victorian Society of Fine Arts’s first exhibition; amongst a stellar gathering including Strutt, Von Guerard and Chevalier. The only other woman exhibiting was Georgiana McCrae, better known as a diarist. Ellen submitted a Saint Cecilia, for which it is recorded several girls at the Model School posed.

It was clearly large – the price was £105 – but also over-ambitious. The critics were merciless: “a tremendous thing for a lady to do, but it had much better have been undone.”21 Vieusseux and McCrae had kinder treatment, although their submissions, being a copy and miniatures respectively, would have more suited the conventional view of women’s abilities.

Ellen Davitt had no luck as an artist, nor with her Institute. The private school market was overstocked and, as Marjorie Theobald has observed, Ellen’s Catholicism would have been a disadvantage. It seems that it rapidly failed, taking with it the Davitt’s severance pay.22

Arthur was apparently too ill to be involved in the venture. He had gone to Geelong for the sea air, where he died, on 24 January 1860. Fifteen years later, the memory still enraged Ellen enough for her to refer to her husband’s ‘murder’. She alleged:

I will boldly say that from the moment that notorious bigot, Sir James Palmer, knew that my husband was a Catholic, he made every attempt to deprive him of his office [...] and being unable to find a fault – the office was abolished.23

Sir James Palmer was the Chairman of the National Board of Education, and a prominent Anglican layman. That he was anti-Catholic is not elsewhere stated and would seem to be disproved by the fact that Patrick Whyte, who like Davitt was a Catholic, became headmaster of the Model School in 1863. However, Whyte’s practice of his religion was pragmatic; he married twice outside the church and his daughters were reared as Presbyterians. The fervency or otherwise of Arthur Davitt’s religious beliefs is not known.

Davitt was buried in the Catholic section of the Eastern Cemetery, Geelong, in a handsome monument whose design is attributed to Ellen. Two months later she appealed to her ‘higher tribunal’, aided by the politician James Grant, known for his gratis representation of the Eureka stockade defendants. She even put forward a motion to address the Victorian Parliament, another extraordinary move for a woman, which was “considered in Committee”. This bold and unusual move was declined, and she did not gain extra compensation.24

What she did do was take up public speaking, with a lecture at the Melbourne Mechanics Institute in April 1861. The topic, ‘The Rise and Progress of the Fine Arts in Spain’, was the first of an occasional series over the following year. The Examiner described her as “a lady whose name will doubtless be familiar to many of our readers”, indicating she was a public figure. The lecture was well-received, a vote of thanks being proposed by the writer Richard Hengist Horne. Nobody commented that her speaking in public contravened the prevailing ideal of feminine modesty. Anthony Trollope himself wrote: “oratory is connected chiefly with forensic, parliamentary and pulpit pursuits for which women are unfitted…”25

In Australia Ellen had precursors, with Caroline Harper Dexter and Cora Ann Weekes lecturing at the Sydney School of Arts in 1855 and 1859 respectively. Harper Dexter is believed to have been the first woman public speaker in Australia. All three chose to talk on women’s role, as if justifying their public display. Davitt’s lecture was described as an ‘essay in female heroism’ – something applicable not only to the subject matter, but the performance itself.26

Dexter wore a Bloomer outfit, of short dress and trousers (in 1851 she had lectured on and in this radical costume in Britain, and sparked outrage). She argued for better female education and a role beyond the domestic sphere.

Davitt’s lecture made similar points, while excluding “the pulpit, the bar, and the healing art […] such matters might well be left to man”.

The Age reported her lecture as an “exposition of the capabilities of the sex not only to perform their domestic and lowly works, but also, when called upon, to play a conspicuous part in the world’s history, as shown by the high position they had taken in literary, artistic, and even political life”.27

The newspaper reports on her public speaking were generally favourable:

Mrs. Davitt’s lecture […] is a literary work of great ability, displaying a large acquaintance with history and both English and foreign literature. The style of composition too is both easy and pleasing, and the extracts remarkably well chosen. The lecturer whose delivery is effective and pleasing was repeatedly applauded in the course of the evening and, as far as we could gather, the audience were generally well pleased, both with the subject and the manner in which it was treated.28

The titles of her lectures – ‘The Influence of Art’, ‘Colonisation v. Convictism’, ‘The Vixens of Shakespeare’ – indicate she was positioning herself as what we would now term a public intellectual. Such was extraordinary, given her gender, the contemporary bias against women orators, and the frontier society of colonial Australia.

Probably in need of funds, Ellen returned to teaching, in country Victoria. For a year, from August 1862 to September 1863, she taught in Portland, at Common School 510, formerly a Catholic school, but from 1862-71 under the Board of Education. Her successor at the school was another remarkable Catholic woman, Mary MacKillop.29

Ellen left for a new career as a public speaker, touring through country Victoria. Such lecture tours were frequently advertised in colonial newspapers; but no other contemporary woman in Australia is known to have attempted the feat. It was here that she revealed the Trollope connection. Fortunately Anthony Trollope had yet to write his He Knew He Was Right (1868), which includes a most unflattering depiction of a female lecturer. Ellen also told journalists she planned to return to England as a lecturer to prospective emigrants; something that did not occur. Instead, she turned to literature.30

It is not known when she started writing, but certainly she had the example of the Trollope in-laws. The chief inspiration would not have been Anthony, but his famous mother Frances. She also was an independent-minded woman, who began a family writing trade with a bestselling travelogue. Her novels significantly contain crime elements, notably the mystery Hargrave (1843), which also includes a romance. Other women drawn into the Trollope circle by marriage took to writing, notably the two Ternan sisters, Maria and Frances (sisters of Dickens’ mistress Ellen), the latter of whom married Anthony’s brother Tom. Anthony wrote, in his short story ‘Mrs Brumby’, authorship “seems to be the only desirable harbour in which a female captain can steer her vessel with much hope of success”. However, there is no evidence that he assisted his wife’s sister; nor that she exploited his name in placing her work.

Because of Australia’s origins as a penal colony, crime content figured in its literature from the beginnings. Generic crime fiction form, as found in Force and Fraud, came later. Content and form only began to coalesce in the 1850s, the era of the sometimes lawless goldrushes, when interest in Australia was an intense, auctorial selling point. Expatriate John Lang (1816–1864), the first Australian-born writer, combined crime matter with the detective in his novel The Forger’s Wife (1855), set in convict-era Sydney. The novel was vigorous and realistic, most notably in the character of the thief-taker (bounty hunter and proto-detective) George Flower, based on a real-life Sydney identity, Israel Chapman. However, the work was more of a picaresque adventure than a formally structured detective mystery; Flower getting his results by guile and violence rather than deduction.

On 26 January 1865 the first known Australian example of the detective story appeared, published in the supplement to the provincial Hamilton Spectator. ‘Wonderful! When You Come to Think of It!’ was a sprightly parody informed by Poe, with a detective fiction fan becoming an amateur sleuth. The author was named as M. C., whom Nan Bowman Albinski has identified as almost certainly the teenage Marcus Clarke, later to become famous with His Natural Life. Clarke owned detective story books, and in the original serial version, his novel had the murder mystery structure. “Wonderful” was followed by another newspaper story: “Experiences of a Detective” by E. C. M., narrated by a police detective, though less lively work.31

These works had no apparent influence on Force and Fraud. It was a genuine original, well ahead of its time and literary context. Nor was it apparently her first publication, as she was cited as the author of Edith Travers (as yet untraced).

The novel was the lead serial in the first issue of the Australian Journal: a Weekly Record of Literature, Science and the Arts (2 Sept. 1865). The magazine was closely modelled on the London Journal, also a fiction magazine, but with a difference – its major subject matter was crime. As such, it reflected not only a national preoccupation, but also the experience of the first editor, George Arthur Walstab, a former policeman.

That Force and Fraud opened this new venture indicates that Ellen Davitt was a staff and star writer. Consequently the AJ worked her into the ground. The novel was followed by two more, and a novella, all published in the first year of the journal. This formidable output meant quantity over quality. Only the debut is republishable, as a work which she had the time to craft, and even probably revise. One serial, Black Sheep, was so hastily written that the main character had two different names. Continuity errors can occur in serials, where early drafts get published without the chance of revision. Indeed, Force and Fraud’s lawyer Argueville first appeared as Arqueille.32

Force and Fraud’s narrative begins with a murder, and ends with the solution – plus a romance added to the plot. Modern readers will note that it lacks a hero-investigator, but at the time that narrative mode had not gained genre dominance. An alternative model equally existed, splitting the role of detective among various characters. It can be seen in works such as Wilkie Collins’ 1860 The Woman in White; and even as late as Fergus Hume’s 1886 The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, the best-selling detective novel of the 1800s.

In Force and Fraud, the investigators include a lawyer, the feisty heroine Flora, and a Scottish shepherd. But there is equally a cast of those seeking to obstruct justice and impede the investigation, as with Frances Trollope’s Hargrave.

Ellen Davitt used her knowledge of art in the depiction of hero Herbert Lindsey. Much of her Australian experience is reflected in Force and Fraud. She had closely observed country townships, and bush homesteads. Her depictions are vividly realistic, adding to the novel’s credibility. One scene, a charity bazaar held at the Melbourne Exhibition Building, was drawn from life. In 1856 such a bazaar was held, and Ellen Davitt presided over the stall of the Commissioners of National Education.33 Not many writers would have used such a domestic, indeed female scene in a crime novel, nor used it to introduce a vital if rather unprepossessing clue. Moreover, the dramatic near-shipwreck on Kerguelen’s land had actually happened to the Davitts.

Anthony Trollope was not a fan of literary puzzles, unlike his mother. “I abhor a mystery,” he wrote, adding that he had “no ambition to surprise” the reader. He refused to construct his plots in great detail before actually writing his novels. In this attitude, he differed from his sister-in-law.

Force and Fraud, a novel whose title is explained in the final sentence, was clearly plotted intricately beforehand. Ellen Davitt understood the importance of clues, of mining the text with details, initially insignificant, that later become vital. She was also adept at red herrings.34

Her other efforts for the AJ tend towards melodrama, although her last serial The Wreck of the Atalanta (1867) had mystery elements. The AJ described it as “certainly the happiest effort of MRS. DAVITT’S pen, and we promise our readers a rich treat in its perusal”.

To a modern reader, though, the serial is interesting largely for its sympathetic portrayal of a battered wife. It is otherwise flawed, its mystery plot lacking the finesse of Force and Fraud.35

Subsequently, Ellen’s name began to disappear from the magazine. She had always proudly signed her works ‘Mrs. Arthur Davitt’, ignoring the Victorian convention that women should publish anonymously. Her contemporary on the AJ, the remarkable police procedural writer Mary Fortune, always used a pseudonym. Ellen’s stories now gained the byline “by the author of Edith Travers, etc.”

Such happened with ‘The Highlander’s Revenge’ (AJ, 31 August 1867). This story is included in this edition as a crime, rather than mystery story. It was the best of her short stories and a significant early fictionalisation of European atrocities against Aborigines. Possibly the editor thought the bloodthirsty matter was unsuitable to appear under a woman’s name.

Almost certainly Ellen had met an eyewitness to the 1840s massacres in the Gippsland region; identifiable here from the details, such as the cannon loaded with glass, and the role of Scots settlers, who having been dispersed from their homes via clearances, were singularly keen in inflicting the same upon Aboriginals.

‘The Highlander’s Revenge’ comprises two stories, a memoir of genocide, and the reaction to it from an audience; yarners around the fire in a bush hotel.

The convention of oral narratives, as with the Canterbury Tales, was used in contemporary Australian writing. One instance was the pseudonymous ‘William Burrows’ whose 1859 memoir, Adventures of a Mounted Trooper in the Australian Constabulary was published in London by Routledge, Warne, and Routledge. Another appeared in the Christmas 1865 issues of the AJ, at a time when Ellen was a major writer for the magazine. It seems likely the ‘The Highlander’s Revenge’ was written for the series, and possibly rejected as too strong meat.

It is interesting that part of the story was reprinted in the Gippsland Times (10 Oct. 1867, 4); the incident described being apparently recognisable. Missing are the worst of the atrocities, and the frame story, which shows the audience reaction. The listeners range from supportive to being utterly appalled; bloodthirsty to anguished white liberal, in our terms.

What was Ellen’s position on the issue? In this subtly-nuanced story, watch how the murder of the speaker’s uncle is paralleled with the treatment of an old black man; a point at which the speaker seems to lose all vestige of his civilisation. She first engages reader sympathy and then lets the narrator’s own words damn him utterly, a powerful act of alienation. A very sophisticated writer can be seen at work here.

This skilled story apparently drew little attention; the Gippsland reprint apart. After 1868 it is impossible to trace Ellen’s publications, although in September 1869 her name appeared in a list of contributors to the AJ. She may have continued writing anonymously, or working as an editor, for on an 1874 application form she coyly stated her profession as “Connected with literature”. Most likely she was writing the women’s content of the AJ.36

In 1874 Ellen applied to rejoin the State Education system, which sent her to Kangaroo Flat, near Bendigo. At this point her story repeats itself, becoming again a tale of bureaucracy, intransigence, and jerrybuilt school buildings.

This school consisted of an eccentric but sound brick building, for the use of the male teachers and students; and for the females a weatherboard ‘lean-to’ which Ellen described as: “wet, ill-ventilated and dilapidated”. Conditions were so bad, she claimed, that “pools of water stood on the floor, and the chalk was literally washed off the black-boards”.37

The leaky classroom was not the only cause of stress, another being the Head Teacher, John Burston. Prior to Ellen’s appointment as first assistant he had expressed a bias against female teachers, and suggested that the job go to his brother Harry, who also taught at the school. The arrival of a middle-aged woman with a strong personality would not have impressed him.38

The situation was physically and mentally unpleasant for Ellen. She had not been given a teaching certificate, despite her previous experience, and was being paid at the lowest rate of salary for her position. Burston was trying to get rid of her, and it seemed she would soon be dismissed, as both he and the School Inspector found her teaching unsatisfactory. However, events took a dramatic turn.39

A dispute with some parents led to an inquiry into Burston’s conduct; which all teachers were obliged to attend. On 15 April 1875, on a workday which the inquiry had lengthened until 8.30 pm, with, as Ellen claims, most of the teachers “fasting from the morning”, Burston lost his temper. In response to being called a liar, he struck Robert Farman, the Chairman of the Inquiry, in the face and the pair grappled on the ground before being separated. From a Victorian viewpoint such behaviour would have been particularly offensive because of the presence of women. One teacher, Charlotte Toogood, had hysterics.40

Burston was immediately suspended; and Ellen Davitt, as first assistant, was placed in charge of the school. She was soon removed, however, due to the regulation that women were not to control schools of over 70 pupils. Harry Burston, who had also behaved violently during the Inquiry, was put in her place. Subsequently, to quote Ellen, there “was a vulgar affair at the Courthouse” in Bendigo, with Farman suing for assault. Burston was fined 20 shillings, and ordered to pay costs. Subsequently he was transferred to Taradale State School, as its Head Teacher.41

Ellen had what she described as a “somewhat sensitive constitution” and had found duties at Kangaroo Flat “fatiguing”, taking frequent sick leave. Now “her health gave way”, to use Allan’s words, although he did not explain the circumstances leading up to her illness. Within several months she was unfit to work again and applied for compensation.42

Her situation was desperate, for the old age pension did not yet exist and she was facing destitution. “I am a widow and stand alone”, she wrote. Certainly she had a case and she argued it well: “there is not a scullery maid in the Colony who would have stood to do her work in such a wretched place”. Compensation was refused, though, on the grounds that she had received in 1859 the sum of £500.43

Very likely Ellen told Anthony Trollope about these events. He visited Australia that year, where his son Fred was squatting in New South Wales. Ellen noted that “Mr. Trollope called on me”, at the school, during working hours, in early May 1875. Anthony’s account of his trip, published as The Tireless Traveller, describes a visit to the quartz mines of Bendigo. It does not mention Ellen, nor does she appear in his fragmentary diary of his earlier Australian visit, in 1871; nor indeed in any of his other writing. Their relationship may not have been close, as he visited her for an hour only. Incidentally, Trollope’s best Australian friend, George Rusden, had been a member of the National Board of Education during the Davitts’ time at the Model School.44

Ellen kept determinedly applying for compensation, and although “not equal to the fatigue of calling” on the claims investigators, as she stated in a letter of 15 Nov. 1877, supported herself by privately teaching ‘Drawing and languages’. On the 29th of that month, the Minister for Education declined to re-open her case. Thirteen months later she died of cancer and exhaustion, on 6 January 1879, at 62 Nicholson Street, Fitzroy.45

There was probably just enough money to transport her body to Geelong, where she was buried beside her husband, but not enough to inscribe her name on the vacant side of the joint memorial.

This omission was rectified by the Melbourne members of Sisters in Crime Australia, with the permission of the Geelong Cemetery Trustees and the Trollope family.

Ellen Davitt’s true memorial, though, is Force and Fraud – a unique and accomplished early Australian murder mystery. The Davitt Awards for Australian women’s crime writing, presented annually by Sisters in Crime Australian, is rightly named after her, for she was a significant pioneer of the genre.