Читать книгу The Bowl with Gold Seams - Ellen Prentiss Campbell - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

April 1985

Clear Spring Friends School is rich in everything money can’t buy. But sometimes, money doesn’t hurt. I needed the meeting with Dick Wilson to go well.

“He’s getting out of the car,” I said to Sally. “Wish I’d worn my suit.”

My secretary stood beside me at the window, looking down into the parking lot.

“You’re fine,” Sally said. “Just tuck in your shirt, Hazel.” I was in my white Mexican market blouse and slacks. “Check out his bald spot.”

Dick was bending over his silver Mercedes, leaning in the window. I could see his daughter, slumped in the passenger seat.

“She’s in the car,” I said. “So she’s better.”

“If she was sick,” Sally said.

“Let’s hope she’s not pregnant,” I said.

“No boyfriend.”

“So?”

Dick pounded on the roof of the car.

“Poor kid,” I said. “No wonder she’s the way she is.”

“Here he comes,” said Sally. “Do you want coffee?”

“I want a drink.”

“Hazel.” Sally looked at me, hard. She has one blue eye, and one green, wears her long gray hair loose, doesn’t use and doesn’t need make up. I call her the Quaker Angel.

The fire door at the bottom of the stairs groaned open. Footsteps sounded on the stairs.

I retreated into my office. Sally and I share a suite on the second floor. The building was the dorm originally, until we built the new one. Weekday boarding for kids like Louisa is our niche market. And revenue stream.

“Good morning, Dick,” I heard Sally say. “Coffee?” We go by first names here, Quaker custom. No one ever calls me Mrs. Shaw. Almost no one knows I was married briefly forty years ago, when I was just a bit older than my own high school seniors.

“No, thanks,” he said, marching into my office. He didn’t shake my hand, squeezed his lobbyist’s expense account girth into the chair.

“Dick,” I said, “We’ve been concerned about Louisa.”

“That’s why I’m here.”

Again. The girl had generated trouble from her first week as a transfer last year when she accused her roommate of stealing her ring. Louisa went home for the weekend and returned wearing the ring—without apologizing to her roommate.

“I hope it’s nothing serious. She’s missed almost a week of classes, Dick. It’s Thursday.”

“I know what day it is,” he said. His pale eyes were chilly and smug. He was enjoying this. He’s like this with her, I thought.

“What is it? We want to be of help.”

“Then get rid of the teacher who attacked her.”

“What do you mean?” My stomach clenched.

“That black French teacher. Toto. Tutu. He groped her. Kissed her. Good thing my girl’s feisty.”

Jacques Thibeault, from the Ivory Coast via Columbia University, was one of my best.

“When does she say it happened?”

“It happened Friday. After school.”

“Why didn’t you tell me at once?”

“Lou was a total basket case. I put her on Valium.”

Since when are you a doctor, I wanted to say. Something else to smuggle back on dorm, like the vodka. The absentee mother was in and out of rehab.

“I’m sorry to hear that, Dick.”

“Not as sorry as you’re going to be.”

Never show a vicious dog you’re afraid, my father always said.

“Dick, we’re not adversaries. We both have Louisa’s welfare at heart.”

“Glad to hear it. When you’ve got rid of him, she’ll be back at school.”

“I need to talk to Louisa, Dick.”

“No one’s upsetting my little girl any more than she’s already been upset.”

“Sidney could be there too.” Sidney’s a psychiatric nurse, in charge of the infirmary.

“I’m not having her interrogated.”

“Just me then. Ask her to come in.”

He shot a glance at me, like a kid caught hiding someone in his room.

“I’m not parading her around,” he said.

“Then let’s go out. Though my office is more private.” Giving him the illusion of choice.

He heaved himself out of the chair. “Don’t make her cry.”

Louisa sat scrunched down in the back seat, wearing sunglasses and a floppy beach hat. She’s a plump, pouty brunette. Probably she favors the mother we’ve never met.

Dick tapped on the window. She opened the door a crack.

“I told her, baby.”

I opened the door on the other side. The air was stuffy, and heavy with expensive perfume. Opium. She must have bathed in it. What sort of father would let a teenage daughter wear such a scent?

“May I come in?”

She didn’t move.

I slid in beside her on the back seat. Dick sat in the driver’s seat.

Louisa stared straight ahead, sunglasses and hat like a protective mask. There were tear tracks and smudges of black mascara on her cheeks. Her hands were knotted in her lap, hot-pink nail polish chipped and the cuticles ragged from picking.

Poor kid. I almost reached out to touch her shoulder, to console her.

“Louisa, can you tell me about it?”

“He told you.” She turned away. Now all I could see was the back brim of the hat.

“I’m sorry, but I need you to tell me.”

“Go ahead,” Dick ordered. “How he grabbed you. Kissed you. Stuck his hand down your pants, your shirt. How you had to fight him off.”

“Dick, maybe Louisa and I could chat privately.”

“No one’s leaving you alone with her, baby, don’t worry,” he said.

“Get out, Daddy.”

He swiveled around. “Don’t say anything if you don’t want to. Like Uncle Bobby told you. My lawyer,” he said to me, with a bully’s smile that didn’t reach his flat blue eyes.

“Just get out of the car already, Daddy. Let me get this crap over with, if you don’t mind.”

“Watch your mouth with me, young lady,” said Dick, glowering, but getting out of the car, slamming the door. He stared in the windshield at us.

“Fuck off, Dad,” she said, loudly.

He turned around and sat on the hood.

She shrugged. “What do you want to know? It’s like he said.”

“Louisa, to get to the bottom of this, I need you to tell me.”

“Get to the bottom of this? That’s great. That’s great. He grabbed my ass, that’s what. My tits. And stuck his tongue in my mouth.”

“That sounds scary,” I said.

“Disgusting is more like it, but you wouldn’t know,” she said. “His wife is pregnant, big as a whale. Guess he isn’t getting any at home.” Angelique Thibeault, a PhD candidate at Georgetown, was expecting their first child.

“Louisa, exactly when, and where?”

“He told you.” Did she not want to talk about it? Was she afraid she’d get it wrong?

“Please, Louisa. What you say really matters.”

“Oh, right.”

“I mean it.”

She took off the sun glasses. Her eyes were glassy, dull. Tranquilizers or pain?

“So I have French last period. He told me to stay after. Said he wanted to help me with the stuff I’d screwed up on the quiz. It’s so noisy on dorm I can’t study right.”

“And then what?”

“Everyone left. He was sitting on his desk. I went up. And he grabbed me. Like I told you. Stuck his tongue in my mouth. Grabbed my tits. How much gory detail do you want? Are you getting off on this?”

Her eyes welled up. I didn’t have a Kleenex.

“I’m sorry, Louisa. It’s hard to talk about. Has—has anything like this ever happened before?”

“Oh, he’s looked at me.”

“I mean—has anyone, anyone kind of in charge, touched you?”

“He’s my first pervert, if that’s what you mean.” She put her sunglasses back on. “So how do I get my stuff off dorm? I’m out of here.”

“We are going to sort this out. There’s still six weeks until graduation.”

“I’m in at Sweet Briar.” Her mother’s alma mater. We’d never sent a kid there.

“They’ll look at your final grades.”

“There’s a building named after my grandmother,” she said, abruptly getting out of the car and slamming the door. She sat on the hood with her father.

I walked to the front of the car.

“So, you get what you needed?” Dick asked.

“I appreciate Louisa’s effort.”

“How do I get my things? I don’t want to talk to anyone,” she said.

“You don’t need your stuff, baby. You’ll be back as soon as he’s gone. And if he’s not—I’ll be back. With my attorney. And we know people at the Post.”

“I don’t want it in the paper, Daddy!”

“Don’t worry, baby. We’re dealing with a reasonable person here, aren’t we Hazel?”

The bell rang.

“Let’s go, Daddy. They’re changing classes.” The girl jumped off the hood and into the car.

“So? What’s the plan?” he demanded.

Never show a vicious dog you’re afraid.

“There’s a procedure we must follow, for everyone’s best interest, especially your daughter’s.”

“I’m not interested in procedure. I’m more of an action guy.”

“No one wants to prolong this. In the meantime, I’ll make sure Louisa gets her assignments to work on at home.”

“She’s in no shape to do busy work. And she’s not going to be home long. Or I’ll be back. With reinforcements, if that’s necessary.”

Kids were crossing campus now. Louisa had huddled down so that only the top of her hat was visible. He got in his Mercedes and roared out of the parking lot. I hoped he’d hit every speed bump. Hit hard enough to damage the car, not the child.

“So,” said Sally. “I’ve been watching from up here. Enlighten me.”

“She says Jacques assaulted her. Kissed her, touched her. After class Friday.”

“Jacques? No way.”

“I need to talk to him. As soon as possible. Check his schedule.”

Jacques came in, slender and graceful in a suit and brilliant red silk ascot. Most of my teachers wear corduroy and denim.

“Hazel?”

“I hate to say this, Jacques, but—Louisa Wilson says you assaulted her after class on Friday.”

“Mon dieu, non!”

“I—I have to ask. Were you alone with her at all? Did anything, anything at all, happen?”

“Everyone had left,” he said. “I’d handed back the quizzes in class. She’d gotten a D again. I was sitting on my desk, going over my lesson plan for Monday.” He sighed. “She came back into the room. I didn’t even hear her until she was right in front of me.”

“And then?”

“She—she looked like she’d been crying. Pauvre petite, I thought. She asked if she could re-take the quiz. No one re-takes my quizzes, it’s just the policy. I told her not to worry, there was time to improve.”

He stopped. His eyes focused on a distant point behind me, as though he was looking through the wall of my office back to Friday’s classroom.

“And then?”

“I felt sorry for her. I touched her shoulder. Just consolation, you know? Like this,” he said, and reached out. His fingers were light and glancing. I caught a whiff of palm oil. “And I said to her, Ne t’inquiète pas.”

“And then?” My Geiger counter for trouble was ticking.

“Please, I resign.”

“Jacques—I trust you—but for the girl’s sake, and yours, I must know every detail. I’m sorry.”

He looked at me now. “She kissed my hand,” he said. “I pushed her away. She left. And that’s all. I swear.”

“Why didn’t you tell me, Jacques?”

“I was ashamed. I—I thought perhaps it was my fault.”

I almost groaned. “Things happen, Jacques. But you should have told me.”

“Yes. Angelique said so. Hazel, I resign.”

“No. I want you here. But—this is difficult. Her father—her father is angry. And she, she’s a very troubled girl.”

“Please, I resign.”

“No. Now, back to class. Don’t speak of this to anyone. I’ll keep you informed.”

“I tell Angelique everything,” he said.

“No one else.”

He strode out of my office, tall and dignified.

I poured a cup of coffee. Touch the Future! Teach! my mug said. Maybe I’d have a new batch of mugs made. Teach! But don’t Touch!

“So?” asked Sally.

I told her.

“I believe him, Sally. But—I’m sorry for her, and I’m frightened. It’s a mess.”

“That poor, sad child is a mess,” said Sally. “You’re right, to believe him.”

“He should never have touched her. And he should have told me.”

“Yes. But he did. And he didn’t tell you. You can see why.” She looked at me with that asymmetrical gaze, one eye green and one blue.

“I have to call Abel now. He’s going to want a meeting of the Trustees Committee tonight. Could you check the calendar and see if the library’s available?”

“It’s not,” she said. “The P.A. has it.”

Of course, I’d forgotten about the Parents Association monthly meeting. Sally carries our calendar in her head as well as keeping it on her desk.

“My house, then,” I said. The Trustees Committee, the executive committee of the Board, six Weighty Friends as they’re called, easily fit into my living room.

I reached Abel West, Clerk of the Board, at his office at the Clear Spring Bank, the bank his great-great grandparents founded. The family estate where he lives was a station on the Underground Railway.

“Oh, Hazel,” he sighed when I’d told him. “The Committee has to meet right away.”

“My house, tonight. 7:30. Sally will call them.”

“You believe him?” he asked, one more time.

“He made a foolish mistake, not telling me. But I know my teachers, Abel. And I know my kids. I’m sorry for her, but she’s always in the middle of something and it’s never her fault.”

“I trust your judgment. We’ve been through a lot together. We’ll get through this.”

Abel’s the best Clerk of the Board I could ever hope for, and the best friend. When his wife died three years ago after her battle with cancer, I shared with him that I had been widowed, too. I told him that long ago, my young husband, my high school sweetheart, had gone off to World War II and never returned. And I told Abel’s boys that my father had died, when I was about their age. But I didn’t say I understood how Abel or his sons felt. In my experience, no one can. Even though loss and grief are universal, each experience is particular and unique. You got to walk that lonesome valley, you got to go there by yourself, as the spiritual my kids sing in chorus goes.

While Sally was calling the Trustees, I walked over to the infirmary to talk to Sidney. We’re fortunate, having a nurse and counselor in one—good for the budget and the kids. Sidney coaches the girls lacrosse team. She’s young, stocky, and strong. The kids like her though some believe she can x-ray their minds. Sidney cleans wounds and listens with the same fierce attention she displays on the field. She’s tender, though, with the needy ones. Louisa had been a frequent caller at the infirmary.

“Whew,” Sidney said after I finished, running her hands through her short, curly hair as though trying to clear her thoughts. “Starved for affection, Hazel. She doesn’t read cues. Can’t, really. In here, heartbroken, every other week.”

“My gut says—Jacques is telling the truth.”

Sidney nodded. “No way to know for sure, but I think you’re right. I can see her having a crush on him. And he and Angelique—they stand out. It can make someone lonely a little jealous.” She had an uncharacteristically wistful look.

“I know. Birds of paradise among us doves. Do we—do we have to report it?” I asked.

“I’ll run it by CPS as a hypothetical,” she said. “She’s eighteen, thank goodness.”

“How did she do in the Life Skills class?” Sidney teaches Health. Holes and Poles, the kids call it.

“Never took it,” said Sidney. “She wasn’t here sophomore year. But it wouldn’t make a difference, with this, Hazel. It’s not like swimming lessons, drown-proofing.” All my kids have to pass a swim test before they graduate.

“I shouldn’t say this, Sidney. I’m sorry for her but—I wish to god we’d never laid eyes on her. I wish her father had withdrawn her last semester, when I suspended her for the plagiarism.”

“What do you know about why she transferred here?”

“Social problems. And he needed the five-day boarding what with travel and—well, the mother. The grades were so-so. She was a gamble, but Clear Spring is all about the second chance. We had that space to fill on dorm, after Emily left.” And Dick Wilson paid full freight, I didn’t need to say.

“What kind of social problems?”

“Vague.”

Back in the office, I called my colleague Anne, the headmistress at Louisa’s prior school in Virginia horse country. My friend Ted, headmaster of another Quaker school, says all heads of schools live by a code of thieves honor. We borrow from each other, we steal from each other, and we pay our debts to each other. I had taken Louisa off Anne’s hands. She owed me.

“So,” I said to her. “Off the record. If I told you that a certain student I took as a transfer from you last year accused a teacher of assaulting her, would you be surprised?”

“Well, Hazel, you know we can never predict that sort of thing. Not what happens, certainly not what someone says.”

“Right. But sometimes it’s a total surprise, and sometimes not.”

“Let’s just say, off the record, this is one where I wouldn’t be totally surprised.”

I hung up the phone. Maybe I should have read harder between the lines of Anne’s lukewarm reference for Louisa eighteen months back.

Ted says there are things only another Head can understand. It would have been good to hear him say not to kick myself. But there was no way to reach him, already en route from his school in the Hudson River Valley to tomorrow’s annual conference for the Heads of Quaker schools in Washington. If the Trustees’ meeting tonight didn’t go too late, I could still make it downtown and spend the night with him. Without traffic, Clear Spring is less than an hour away from D.C.

Ted says running a high school is like running a crisis center. You have to be able to focus and compartmentalize. I powered through two days work in one, preparing to be out of the office at the conference. Sally brought lunch to my desk. I didn’t feel like being in the cafeteria with the kids. And at the end of the day, she shooed me out.

“Go home,” she said. “Rest before they come. Have something to eat. Not just these cookies at the meeting.” She gave me the tray of snicker doodles, brownies, and chocolate chip cookies from the school cook. “Call me when it’s over, let me know how it goes. And if there’s anything you need me to do tomorrow, while you’re at the conference.”

“Maybe I shouldn’t go,” I said.

“You should go,” she said. “It will help to get away.”

“What did I do with the agenda for tomorrow?” I started to sift through the piles of paper on my desk. She put a cool, firm hand on mine.

“It’s in your briefcase.”

I walked home across campus. The fields had just been mowed. The fragrance of fresh cut grass filled the air. The sun was low, striking the apple blossoms in the orchard at the edge of the school property. Our land is our treasure. A local Quaker gave her family farm to the Founder of the school thirty years ago, when he had his vision and announced to the Meeting that Clear Spring needed a school. Developers have wooed us. We’ve managed to hold out.

I called Ted at the Shoreham.

“Where are you? I have a gorgeous room—looks right into Rock Creek Park.” His school, Maplewood Friends, can provide a good expense account.

“Emergency meeting with Abel and the committee. I’ll come, it may be late.”

“What’s up?”

“Tell you later. Abel will be here soon.”

My mother’s clock on the mantelpiece struck seven. I keep things simple—no pets, no plants; two hundred and fifty kids are enough to take care of, but I wind her clock once a week. It keeps me company. Sitting on the window seat, with a tumbler of bourbon, I looked out across the pond to the cluster of small one-story ramblers, faculty housing. Jacques and Angelique would be there having dinner. The couple rarely ate in the cafeteria. Some faculty live off-campus to avoid the fishbowl, but on-campus housing is a valuable perk in this area. I lived in an apartment on dorm, when I first came here to teach history at the brand new school twenty-five years ago. The head’s house is larger than the rest, set apart—an embarrassment of space for a single woman. It has heart of pine floors, built-in cabinets and book shelves. Our Founder was a cabinet maker.

The front door opened. We don’t lock here. “Hazel?”

“I’m back here!” Abel came in, loosening his tie.

“Offer you a drink?” School events are dry, but private is private.

He shook his head.

“Sidney checked. We don’t have to report it to Child Protective Services,” I said.

“That’s good, I guess. I’d rather handle this in-house.”

We went into the kitchen. I plugged in the coffee urn, uncovered the cookies. Abel carried the tray into the living room, nibbling a snicker doodle.

“I have bread and some good cheese, Abel.” He’s a tall man, and gaunt since his wife’s death.

“Thanks, but I’m not really hungry.”

“I called her former headmistress today. Something similar may have happened there. I’m kicking myself.”

“We were down a kid. What’s done is done. Now we just have to work through what’s best to do for the school,” he said.

“We have to back Jacques,” I said.

“Hazel? Am I too early?” It was Maggie Stadler, the newest member of the committee. Her eldest daughter was a senior this year, bound for Swarthmore. Maggie’s the oncologist who took care of Abel’s wife. She came into the room, put down her knitting basket, unwrapped her shawl, and gave us both a quick hug. If I ever have cancer, I’m calling her.

By 7:30 the committee had gathered: each in our accustomed seats, like a family gathering around a table. I always take the captain’s chair, one of those the Founder made. It’s un-cushioned, and I’m thin so it’s a little uncomfortable, but that keeps me awake.

Abel was in the wing chair by the fireplace. “Good evening, friends. A moment of silence, please.”

We follow Quaker procedure for business meetings—Faith and Practice, not Roberts Rules. We open and close with silence. Listen to each other and for the voice within.

“Thank you for gathering on such short notice. Hazel will explain. We have a most concerning situation,” Abel said.

It was so quiet in the room. The spring peepers in the pond outside were calling. I took a deep breath. I kept my eyes on Maggie, her quick hands, her flashing knitting needles. “One of my students has accused my teacher Jacques Thibeault of assaulting her.”

Maggie put the knitting down in her lap, and looked at me.

“I’ve spoken to the girl, and to her father, and to Jacques. My counselor, Sidney, has been quite involved with the student. She transferred in last year. There have been a lot of issues.”

Sam Jiles interrupted. “Have you reported it to Child Protective Services?”

“Sidney has spoken with them. At this time, it’s not reportable because she’s eighteen. I’ve also spoken with her former school. It’s possible there was a similar situation.”

“Then why did we take her?” said Sam. He’s built like an opera singer, and is a fine baritone. He sings in the community chorus with students, faculty, members of the Meeting. He runs a non-profit, clerks my Finance Committee, and is one of my most generous donors.

“Let’s hold our questions, friends, and hear Hazel out,” said Abel.

“What exactly does she say happened? And what does your teacher say?” asked Dave Furbush. He’s an attorney, estate planning mostly, and has handled some matters for us pro bono. His son graduated two years back, with Abel’s youngest.

“The girl says he asked her to stay after class. That he kissed her, fondled her. That she ran away. Jacques says she left with the others, then came back and asked to re-take a quiz. He told her she couldn’t—it’s his policy—but not to worry, there would be time. He says he did touch her shoulder, out of sympathy. She kissed his hand, he pushed her away.”

“He should have come to you right away,” said Dave, a tense look on his face. He must be almost sixty, like me, but looks much younger.

“He should have. But I believe him.”

Sam shook his head. Maggie was biting her lip.

“Her father demands I fire Jacques. He’s threatening to involve an attorney, the media. Jacques has offered to resign. I have refused.”

“And so, friends,” said Abel, “that’s where we stand. Tonight, we must thresh through this, consider our options, and discern carefully the best course for the school.”

“It’s just she said, he said?” asked Dave. “No witnesses?”

“It was after school on Friday. The kids are at sports.”

“No other teachers at all in the building?” Dave persisted. It felt like I was being deposed, though I’ve known these half dozen good people and their children for years.

“The other two teachers on his hallway coach cross country. So no, no one.”

“And he doesn’t coach anything?” Sam asked.

“He could, if we had the money for tennis courts.” My heart was beating faster.

“Friends,” said Abel. “Let’s not get caught in the weeds here.”

“Okay,” said Dave. “We must consider the best interest of the child: protecting her and all the children, if there’s any chance what she’s saying is true.”

“I agree,” I said. “And I’m worried about her. We’re all about protecting the best interest of the child here. But letting her fabrication and her father’s threats take down a fine teacher isn’t good for her. Isn’t protecting her best interest, in the long run.”

“My daughter’s a senior, too,” said Maggie. “Only one student transferred into the class last year. So, without naming names, I know who this is. Sarah was assigned to be her First Friend.” We have a buddy system for new students. “I don’t, in any way, mean to blame a possible victim—but she struck me as—well, troubled. I would be very, very hesitant to rely on what she says.”

“Just because she’s troubled doesn’t mean she’s lying,” said Dave.

“And you can’t take her being troubled and him being a good teacher to the bank,” said Sam. “Sorry, but I for one think we should accept the teacher’s wise offer to resign, tie this kid in bubble wrap, get her graduated, and move on. I know who we’re talking about too, and I know exactly what the Annual Fund was counting on asking for from her dad.”

I was almost trembling. Stay calm, stay calm, I reminded myself. “There’s something at stake here even beyond the cost of a lawsuit, or losing a gift. Jacques is a fine teacher. And I have to say it—he’s one of our only minority teachers, too. We can’t sacrifice him to slander and extortion.”

“This isn’t about race, Hazel. This could be a game ender. To fund a suit like this might be, we’d have to sell the land. Bankrupt the school, ruin the reputation we’ve worked so hard to build,” said Sam.

“Jacques is exactly the kind of teacher who is building that reputation! Remember my report to the Board about the new Honors seminar in Camus and Sartre? That’s Jacques. With teachers like him, we’re beginning to be able to offer something unique, to attract some really good students.”

“Well and good. But not bankable. We’re not so many years out from our reputation as a hippie haven of free love and drugs, Hazel. Perhaps that’s slipped your mind,” said Sam.

“Sam, Hazel. I want to be sure we have an opportunity to hear from everyone. Friends?”

Abel’s gentle reproach smarted. Once in my early days as Head, I was “eldered” as we Quakers say, called to meet with the then Clerk of the Board and the Founder. Be mindful of letting others speak, the Clerk had said. Measure twice and cut once, the Founder said.

Quaker process is slow. The goal is to come to the shared “sense of the Meeting.” We don’t vote. We discern the Way. We seek consensus.

The clock struck ten, and then half past. The coffee was gone, only crumbs left on the cookie platter.

“I don’t think the child intends harm,” said Maggie. “But I don’t think she’s able to report accurately. Remember when the drama club did The Crucible? As the mother of four girls, let me just say teenage girls can be suggestible. I think we should slow this down, find a middle path. Like a leave of absence for Jacques, just till she’s gone.”

“My friend Maggie speaks my mind,” said Dave.

Nods around the room signaled consensus. Or exhaustion.

Abel looked at me. “Hazel?”

“Friends, ordinarily I would stand aside.” That’s always an option, for the minority voice, rather than obstructing consensus. “But—asking Jacques to take a leave of absence is something I cannot do. It is an expression of no confidence. None of you work with him. None of you really know him the way I do. And—hiring and firing faculty are the Head’s decision.”

“Right,” said Sam in his resonant voice, “and renewing the Head’s contract is the Board’s decision. In June.”

Maggie looked at me, pleading or apologizing. “Could we—could we at least lay this over? Defer a decision until next week?”

“Not if he serves us with papers,” said Dave.

“Not if he’s bringing the media,” said Sam.

“Oh, I don’t think he’d do that,” said Maggie. “What father would expose his daughter to media about something like this?”

Dick Wilson would, I thought.

The clock struck eleven.

“Friends,” said Abel. “The hour is late. I for one am too tired to discern clearly. I suggest, if we agree, that we accept Maggie’s suggestion to lay this over. Just for the weekend. I propose Hazel and I will meet with Jacques on Monday.”

“Tomorrow,” said Sam. “What’s wrong with tomorrow?”

“I’m at the conference for Heads of Quaker schools tomorrow. And it’s too late to get a substitute for Jacques. The girl’s not on campus.”

“First thing Monday,” said Abel. “What do you say, Hazel?”

The illusion of choice.

“Very well,” I said.

“This has been a thorough threshing session,” said Abel. “Thank you, Friends. A moment of silence, please.”

I like our Quaker expressions. ‘Threshing session’ conjures images of neat bales of hay, of harvest brought home. But as I sat in the closing silence, I saw a storm-ravaged meadow.

We adjourned, without the usual chuckles and yawns. There were no cookies left for Sam to wrap up to take home to his wife, or to eat in the car.

Abel stayed behind. He loaded the mugs into the dishwasher. I dumped out the coffee; I put the urn away until our next meeting.

“Please, Hazel, discern with care,” he said.

“Fire him, you mean. Or be fired.”

“No. But I do want thee to weigh the options. Thee must consider accepting his resignation.” Abel had never used plain Quaker speech with me.

We embraced before he left. After Linda died, people wondered about us. But I learned my lesson at my first school about falling in love with a colleague. That’s why I came to Clear Spring, my own second chance. As I used to teach my students in American History, George Washington said to steer clear of entangling alliances.

After Abel was gone, I called Jacques. The lights in his house across the pond were still blazing.

“We’re behind you,” I said. “Abel—Abel and I want to meet with you first thing Monday morning.”

“So they don’t believe me. Even if they did—it’s no good. I want to resign, Hazel.”

“No. Please, Jacques. I want you to stay. The school needs you. We’ll meet with him on Monday. At eight, in my office.”

I called Sally. “Basically, they want me to accept his resignation. Course of least resistance.”

“Maybe you should. There might be a lot of suffering for him and Angelique.”

“Maybe Rosa Parks should have moved to the back of the bus. Maybe William Penn should have taken off his hat to the king.”

“Don’t lecture me,” she said. “I’m just saying I’m worried—about the girl, Jacques, Angelique. You.”

“Thank you. Sorry.”

“Do you need me to call Jacques?”

“I already did.”

“And?”

“I told him I want him to stay. He wants to resign. We’re meeting with Abel Monday morning at eight.”

“Do you want me there?”

“No, thanks. Maybe I should skip the conference tomorrow.”

“Go. Let this settle. Clear your mind.”

I threw my things together—nightgown, toothbrush, outfit for tomorrow. Spritzed Aliage, perfume Ted had given me, which I never wore at school. I drove too fast down the driveway between our playing fields and hit a speed bump. My car is low slung; I’m still getting used to the extravagant red Toyota Celica. The first new car I’ve ever owned. Ted calls it my late mid-life crisis car. It’s a bit embarrassing to park it among the Volvos at Meeting. But driving through the dark night toward Washington with the top down, I pressed the accelerator to the floor.

The carpet at the Shoreham Hotel is deep as moss, and the chandeliers sparkle. It’s the grande dame of Washington hotels. We didn’t need to worry about running into any of our colleagues here. No one but Ted on his Maplewood expense account could afford it. I rode the glossy wood-paneled elevator up. Ted greeted me at the door in his boxers. He’s a small, compact man—a runner.

“It’s good to see you, doll,” he said, kissing me. He’s a good kisser. “Hungry? Want room service?” he asked when we broke apart.

“I’m tired. I just want to go to bed.”

“Sounds good to me,” he said, and ran a finger tenderly down my face, my neck, along my clavicle.

The sheets were heavy and smooth. He gave me a massage, kneading the tight muscles in my back, lavishing attention on my buttocks. We made love.

Afterward, lying beside him, I began to cry.

“What is it?” he said. “You never cry.”

“This thing at school.”

“Tell me.”

“I’d rather hear what’s going on with you. Did Jack like Bowdoin?”

“I don’t want to talk about that, either,” he said with a rueful laugh. “His mother went off her meds again. Went to bed. He had to go on the visit by himself. She wouldn’t do the hospital. Or day treatment. She’s seeing the shrink twice a week. It’s better. For now.”

I met his wife once, long before Ted and I were lovers, back when we were all teachers, attending a Friends Council for Education conference.

“Your turn,” he said.

“I don’t want to talk about it.”

”You’re crying again.”

I told him.

“Oh, Hazel,” he said. “Shit. As if the job weren’t hard enough, and then something like this blows up.”

That’s part of what works between us. We both get it, about the job. We sustain each other, even if it’s just on the margins of our lives. I’m married to my job; he’s married to his job and his wife and has had to be father and mother to Jack. We’ve been lovers ten years, longer than I’ve ever been with anyone. Years and years longer than my marriage.

“Abel wants me to take his resignation.”

“Maybe you should. The kid is definitely lying?”

“I’m as sure as I can be. You know—it’s that instinct thing.”

“Are you sure this is worth going down with the ship?”

“You mean there’s not much of a market for elderly head mistresses, if I lose the job?” Ted’s five years younger than I am: fifty-five. We both know you can’t do this job forever. It’s a tough gig, but most days I feel like I’m doing what I was put on earth to do. I love it.

“Hazel—it’s just your best interest I have in mind.”

“Best interest! I’d be happy never to hear those words again.” I went to the window. He came and put his arms around me.

“Come back to bed.”

“Soon,” I said. “Go to sleep.” I stayed there for a long time, watching the car lights twinkle across the bridge over the ravine.

The next morning, we ate breakfast in bed.

“Eat hearty,” Ted said. “You know it’s going to be the eternal chicken salad today at Penn House.”

I took his advice and enjoyed my brioche, the butter curls on ice, the coffee from a silver pot. It was good, being beside him, warm animals in a burrow. We ate; we read the Post, the Times.

“Here’s a story for the kids in your seminar,” he said. “Reagan’s so-called peace proposal in Nicaragua.”

My Peace Studies seminar is the only course I teach now. I tie history to current events.

“Mark it for me. How about seeing this, next time we can meet in the City? New Neil Simon. Biloxi Blues.”

“What’s it about?” he asked.

“Soldier on the G.I. newspaper. Guilty about how the war is helping him.”

“Speaking of guilty—come here.”

Afterward, we dressed.

“That a new jacket?” he asked.

“An early birthday present. The weaving teacher made it. She says when you turn sixty you have to start wearing purple.” My birthday wasn’t until June but the teacher (also my friend as often happens at Clear Spring) understood the approaching milestone felt significant, even a little frightening. Both my parents died young; far younger than I am. For years I have had an increasing sense of being on borrowed time; everything I do must matter. The weaving teacher’s frivolous gift and fashion advice had cheered me.

“You’re getting a head start on this birthday. I’d better start planning.”

We shared the mirror. I did my makeup, enjoying the neat economy of his gestures as he tied his tie, fastened cuff links.

“Leave your stuff. I have the room tonight.”

“I should get back.”

“Tomorrow. You’ll think more clearly after a break.”

“Won’t think at all, if I spend the night.”

I gathered my things, packed my bag. I did stick to my resolve. I did not spend the night with him. But although I had no way to know it then, the conference would disrupt everything. The past was about to grab me by the throat and drag me away from the crisis at school.

We travelled separately to the conference at Penn House on Capitol Hill. I parked on C Street. I come into the city as often as I can, on field trips. Soon, we would make our annual school bus pilgrimage to see the cherry blossoms at the Tidal Basin. Vigilantes tried to destroy these trees after Pearl Harbor, I tell my kids in Peace Studies, because the Japanese gave them to Mrs. Taft.

But the trees didn’t do anything wrong, someone always says.

No, but when elephants fight, the grass gets trampled.

Penn House looked shabby next to its patrician neighbors. Lilies of the valley lined the weedy brick path. The broad front door was open. Only Quakers would leave a door open here.

“Hazel,” said Jane Samuels. She’s the resident director of Penn House. In her perennial uniform of navy blue skirt and white blouse, she looks like a nun in street clothes. She was a nurse in Vietnam, and did jail time for pouring blood on the draft files in Catonsville.

I slipped into a seat at the long mahogany table, polished and gleaming despite stains from years of meetings. Marilyn Bartlett, head of tiny Hilleston Friends in Virginia, sat down beside me. Ted was already there, across the table.

“Good morning, friends,” said Jane. “A moment of silence.”

Ted bowed his head. He has thick, salt-and-pepper hair. I closed my eyes. It would be second period by now at school. How was Jacques managing?

Jane cleared her throat “So, it is my pleasure to welcome our keynote speaker. Dr. Bledsoe is on sabbatical from Oxford, teaching at George Washington University. Many of you are familiar with her research on cultural identity among children, so helpful as you include children of different nationalities in your student bodies. Please join me in welcoming her.”

Polite applause greeted the speaker as she stood and moved to the podium.

She was slender, wearing a simple, expensive linen suit. Eurasian—part Japanese, I thought.

“Thank you. I am delighted to address Quaker educators, for I have experienced the kindness of Friends. As Jane said, I study the development of national identity—with a special interest in trans-national children, children with feet in two cultures.” Her voice was low, the accent neither BBC nor Oxbridge. “My topic chose me, as is often the case. My mother was English, my father Japanese.” She adjusted fragile, gold-rimmed glasses with small, delicate fingers. “Complicating my own question of identity, I spent the first years of my childhood in Berlin, during the war, as my father was attached to the Japanese Embassy. In 1945, we were detained in the States at the Bedford Springs Hotel, in Pennsylvania. I was thirteen.”

It was like skidding onto unexpected black ice. I had known her, known her parents. Closing my eyes, I saw a small hand waving good-bye, flickering from the rear window as a black limousine drove away down the hotel’s driveway.

At the coffee break, I chatted with Marilyn and then retreated into the ladies lounge. The room was furnished with wicker and lined with age-spotted mirrors dating from when Penn House had still been a private home.

Dr. Bledsoe stepped into the room and slipped into a toilet stall. Twisting the faucet, I splashed cool water on my face and blotted it dry. She emerged and stood beside me, dusting her cheeks with powder. Our eyes met in the mirror. Hers were unchanged: almond-shaped, smoky gray-green.

“Cha-chan,” I said, “Charlotte—I’m Hazel. From the Springs.”

She froze.

Jane popped through the door. “Oh, here you are. Wonderful! Dr. Bledsoe, I wanted to be sure you met Hazel Shaw. Head of Clear Spring Friends—she’s developed a Peace Studies course. You two should talk.”

Charlotte Harada Bledsoe turned and smiled at Jane, perfectly poised. A diplomat like her father. A performer, like her mother. “Thank you. In fact, we’re old friends.”

“Really? What a small world it is! Find us at lunch, Hazel. You can catch up.”

But at lunch, I did not eat with Charlotte. She was besieged; everyone had questions.

“You knew her when you worked there?” Ted asked softly as we stood in line for chicken salad.

I nodded.

We ate with Marilyn, balancing plates on our laps, sitting in the narrow garden behind the townhouse.

“At my school, we haven’t ever had a foreign student. Unless you count the family that moved from New York,” said Marilyn.

“I get the occasional U.N. kid,” said Ted.

“How about you, Hazel? Diplomats’ kids?” asked Marilyn.

“They go to Sidwell,” I said. “We’re like Avis. We try harder. I have a Republican though. How’s that for cultural diversity?” Louisa Wilson, my Sweet Briar girl.

At the end of the afternoon, Jane sought me out. “Join us for dinner. Just Dr. Bledsoe and me. There’s a Japanese place near the Cathedral.”

The restaurant was small. The kimono-clad hostess exchanged a few words with Charlotte in Japanese, and seated us at one of the traditional low tables. The green tea hit my blood stream like elixir.

“Now how is it you two know each other?” asked Jane.

A pause. “Hazel worked at The Bedford Springs, where my family and I—stayed.” Polite euphemism, stayed. Diplomat’s daughter.

“Where is that, exactly?” Jane’s eyes sparkled with gentle curiosity.

“Bedford’s about half-way between here and Pittsburgh,” I said.

“I’m going there tomorrow,” said Charlotte. “To the Springs.”

“Could I come with you?” I asked, surprising myself.

“I would like that.”

Jane ordered sake. “A toast to your reunion,” she said.

We touched our porcelain sake cups together.

I drove the fifteen familiar miles back to campus. Turning between the brick bollards marking the school drive, I noticed our sign had been vandalized again. Clear Spring _ _ _ ends School, it read. A practical joke by one of my seniors, most likely.

I called Sally. “So, how was it today? Anything more from Louisa’s dad?”

“Not a peep,” she said. “Try and get some rest over the weekend.”

“Actually, I’m going away tomorrow. Just overnight. I met an old friend at the conference.”

Sally, my Quaker Angel, sees right through things with her bi-colored eyes. She may suspect, about me and Ted. Perhaps that’s why she didn’t press for any details about my plans.

“Good,” she said, “That’s good. Try not to worry. Way will open.”

“Could you tell Thomas the sign needs to be re-painted again? Wish we could figure out who’s doing this, bring him to P&D.” The Head, the Dean, two teachers, and two students sit on the Procedures and Discipline Committee. Louisa had been brought before us, after trying to hire another student to write a paper. The boy had totally misunderstood her request, she said. I just meant for him to proofread, check my spelling!

I started to pour my bourbon, but selected the unopened bottle of Suntory instead.

“I thought you didn’t like whiskey,” Ted had said when I bought it in Manhattan.

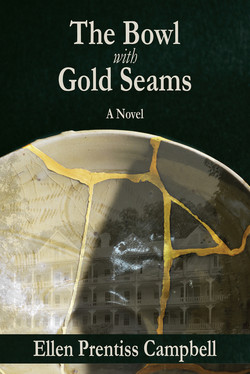

I retrieved something else from the very back of the cabinet, carried the small package to the table and unwrapped layers of tissue paper. The black pottery bowl had been broken and mended, the shards joined together with golden glue. The bowl’s design of blossoms and Japanese characters seemed caught in a net of shining gold seams. The long-ago artisan who fused the fragments with seams of lacquer dusted with powdered gold had transformed breakage into beauty, highlighting the damage as part of the bowl’s history rather than hiding its repair.

I used to display the bowl on the mantel beside my mother’s clock. One year, at my Head’s reception for entering students, a new parent said, “That bowl is a glorious specimen of kintsugi. Where ever did you get it?”

“A gift from a friend,” I said.

Afterward, I had it appraised at the Freer Gallery and learned kintsugi was born of a serendipitous accident in the fifteenth century. A shogun sent a broken tea bowl to China for repair. Dissatisfied with the way the mending’s visible staples marred his bowl, he ordered a Japanese artisan to re-break it and repair the bowl with golden glue. The fractures made a gleaming pattern and kintsugi—golden joinery—developed into a ceramic art form. The Gallery’s estimate of the bowl’s value shocked me so much that I hid it away deep in the cabinet. Really, I should have put it in my safe deposit box. Someday it could supplement my pension. Or I might leave it to Clear Spring, bequest from a dead hand, no questions, no explanations possible.

I placed the bowl on the mantle, broke the seal on the Suntory and had my drink.

Upstairs I pulled the cord in the hallway ceiling for the attic ladder. I brought down a cardboard carton and opened it. The smell of dry paper and paste reminded me of grade school, of the Bedford library on a summer’s day. Like a good historian, I made neat chronological stacks of papers across my bedroom floor: recital programs, my yearbook, letters, V-Mail, newspaper clippings. A folded piece of rice paper, black ink bleeding through the translucent page. A heavy envelope from the War Department.

Primary sources connect us directly to the past, I teach my students.

Neal’s photograph watched me from the bureau. Young, not much older than my boys at school. His expression was serious, his jaw set and square.

The phone rang.

“How was dinner?” Ted asked.

“Fine.”

“Are you okay?”

“More or less.”

“Less, it sounds like,” he said. “Come back.”

“I’m leaving early in the morning.”

“Where are you going? I thought you had to be at school.”

“To the Springs. With Charlotte Bledsoe.”

“So she was one of the children?”

“Yes.”

“Wow. What are the odds? Amazing.”

“Yes.”

“You sound strange. I miss you,” he said.

“I miss you, too.”

But it wasn’t Ted I missed. I carried Neal’s photo to my bedside table; black and white, but I saw the wheat color of his hair and the green flecks in his brown eyes. His lips were closed but I remembered how soft and warm they were, and the space between his two top teeth.

The half-remembered lament from the tenth century Japanese poet Murasaki Shikibu floated into my mind. Why did you disappear into the sky?

I held the picture, looking into Neal’s eyes, as though the lifetime I had lived since he died, the lifetime of years between us was dissolving. Lying awake, I listened to the hours chime and stared into the shining darkness of the past.