Читать книгу A Theater of Diplomacy - Ellen R. Welch - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

National Actors on the Ballet Stage (1620s–30s)

Court entertainments may have appeared as strangely obscured focal points in most ambassadors’ writings.1 This scarcity of commentary, however, only means that diplomatic spectators rarely recorded their observations, not that they completely discounted entertainments’ content. After all, many spectacles concentrated on themes of professional interest to diplomats, including sovereignty, war, and peace. Although diplomats who witnessed entertainments had little to say about their subjects, the creators of court spectacles insisted on the power of ballets to communicate. Theorists stressed that engaging subject matter was the most important element of a successful entertainment. One of the first ballet manuals, designer Nicolas Saint-Hubert’s La manière de composer et faire réussir les ballets (The Way of Composing and Successfully Producing Ballets, 1641), began: “I will start with the subject, upon which depends all the rest.”2 The music, choreography, and all other elements of the spectacle must “accommodate” or “subject themselves” to the representation of the thematic content.3 Describing ballet as a kind of “mute theater,” Saint-Hubert insisted that its primary goal was to transmit meaning to its audience.4 In the following decades, Michel de Pure echoed the comparison of ballet to a “mute drama” while Claude-François Ménestrier preferred the analogy of the “speaking painting” to evoke ballet’s particular communicative power.5

In fact, ballet offered artists a unique set of representational resources well suited to the depiction of political ideas. Characterization—perhaps the key artistic building block of pageant-like early modern ballets—lent itself to reflections on autonomy, sovereignty, and (political) action. This was especially true of ballets that depicted characters invested with national traits. Figures marked as Spanish or Italian, as Turks or Moors, populated the earliest court entertainments. The Roman, Greek, Moorish, Spanish, and Scottish costumes worn by participants in the jousting tournament at the Bayonne Conference (discussed in Chapter 1) suggest some of the traditional uses of national masquerade, adding visual interest to chivalric sports. In the thematically focused setting of court ballets, dancers in national garb allowed for the depiction of political events and relations. As early as 1580, for example, Henri III commissioned an informal chamber ballet in which performers in Spanish and Portuguese dress enacted France’s vision of the crisis of Portuguese succession.6 Whether used for visual appeal or political commentary, the representation of national figures remained a staple of court performance throughout the early modern period.7

In the early decades of the seventeenth century, ballets that featured national characters among their dramatis personae also began to comment on the representational techniques that constituted nationality. The dominant form of the ballet à entrées—a series of independent solo or small-group performances, loosely linked by an overarching theme—lent itself to a critical engagement with processes of characterization and differentiation. In ballets with national themes and figures, this investigation addressed political matters. What did it mean to embody, and thereby represent, a collective entity such as a nation or country?

This question resonated beyond the confines of the dancing hall. Dramatic representation provided models for political thought in relation to a variety of problems. As discussed in Chapter 2, thinkers on diplomacy used the analogy of the relationship between author and actor to characterize the sovereign’s delegation of authority to the ambassador. The conditions of sovereignty itself were described by thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes as a form of impersonation through which the absolute monarch assumed the capacity to act on behalf of his subjects. In addition to these well-known and well-studied appropriations of the theatrical lexicon for political theory, other thinkers including Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully, and Emeric Crucé considered how representatives of different states might come together in a confederative governing body to ensure peace. Dramatic metaphors (if metaphor is a sufficient term to describe theorists’ reliance on theatrical concepts) did not simply emerge from the ether. Most political theorists and all the practitioners of monarchal and diplomatic politics inhabited a culture rich in dramatic performances, particularly ballets. Sully, a renowned amateur of dance, not only performed in ballets but commissioned the construction of a state-of-the-art dance hall in his residence at the Arsenal, where he hosted several entertainments for the royal family.8 Even Hobbes absorbed the traditions of court performance through his role as tutor to the Devonshire Cavendish family of English aristocrats.9 In other words, the same individuals who theorized the means by which nations or commonwealths were represented on the political stage also had the experience of witnessing or participating in the playful embodiment of national characters on the ballet stage. How might ballet have reflected on—or even helped generate—models for understanding political representation?

Ballets of Nations

Performances by national characters became a ubiquitous feature of ballets in the 1620s and 1630s.10 An international pageant in dance form, these “ballets of nations” featured a series of performers each costumed in the characteristic garb of his or her particular “nation,” performing a dance conventionally associated with that country (an allemande for a German, a passacaille for an Italian, a sarabande for a Spaniard, etc.). Verses sung or declaimed during the dance referenced popular stereotypes about the character’s ethnicity. Some entire ballets were devoted to such a parade of national types, as in the Ballet des nations scripted by Guillaume Colletet and performed at Louis XIII’s court around 1622.11 More often, a series of performances by national characters made up part of a larger, more diverse entertainment.

Ballets of nations fit perfectly into the dominant form and aesthetic of ballets composed for Louis XIII’s court. The “burlesque” ballets of the period focused attention on the visual: set design, costumes, and virtuosic dance.12 To maximize spectacular variety, most ballets eschewed complex plots, taking instead a disconnected structure as “parades of disparate figures” that relied on characterization to provide most of their effect.13 Seventeenth-century ballet commentators approved of national ballets because audiences could easily recognize the figures they depicted. In this, they followed Aristotle’s contention in part 4 of the Poetics that the greatest pleasure to be derived from contemplation of an image lies in the satisfaction of recognition.14 Jesuit composer Claude-François Ménestrier, for example, remarked in his Des ballets anciens et modernes (Of Ballets Ancient and Modern, 1682) that ballets should “speak to the eyes” with clearly legible imageries.15 Ethnic or national figures rated highly by this measure, for “the diverse Nations have their proper costumes that distinguish them. The Turk has the jacket and turban, the Moor the color black, and the Americans their outfit of feathers.”16 Simply by using the costume traditionally associated with the Moor or the American, the composer could effortlessly and unambiguously convey the identity of the personage to his audience.

Of course, recognizability was not the only factor driving the popularity of ballets of nations in the 1620s and 1630s. National figures appealed to contemporary French aesthetic interest in the exotic.17 In addition, national characters lent themselves to the comic spirit of Carnival ballets with exaggerated costumes and movements and humorous verses that mocked national stereotypes. Although the national ballet’s depiction of foreign countries certainly depended on well-worn types and trite exoticism, the conceit of embodying and performing national identities on the ballet stage deserves deeper consideration as a material artifact of the way some French artists perceived the category of the nation in the seventeenth century.18

In French in this period, the term “nation” designated an ensemble of characteristics presumed to be exhibited by individuals hailing from a particular country. French dictionaries defined the word “nation” as a collective term referring to “all the inhabitants of the same State, of the same country, who live under the same laws, speak the same language, etc.”19 The meaning and usage of the term pertained chiefly to shared cultural traits, or what we might call ethnicity. Nationality had to do with language and with characteristics tied to region and climate. A “nation” could be bellicose or barbarous, refined or rustic. Each nation had its characteristic “genius” that manifested itself in the poetry, art, and music of its progeny.

Although primarily geographical and cultural, the category of the nation also had political connotations. Long before the “nation-state” as such came into existence, dictionary definitions suggested the political relevance of nationality in their observations that the people who constitute a nation live “in the same State” or “under a common rule” and “under the same laws.”20 Discourses about nationality certainly played a role in international politics—for example, in the heated national rivalries that often accompanied struggles over territory or political power. Questions of nationality, moreover, influenced the delineation of frontiers. As Peter Sahlins has shown in his work on the creation of the boundary between France and Spain in the mid-seventeenth century, “both state formation and nation building were two-way processes…. States did not simply impose their values and boundaries on local society. Rather, local society was a motive force in the formation and consolidation of nationhood and the territorial state.”21 Despite the immense cultural and linguistic diversity within both kingdoms, claims that the ethnicity or “nation” of a particular region was more French or more Spanish helped determine on which side of the border it would lie.

In this context, the performance of nationality on the ballet stage enacted, and asked spectators to reflect upon, assumptions about national differentiation. Across the 1620s and 1630s, French court artists experimented with different approaches to characterizing national identities in ballets: earlier examples of the form presented essentially human characters exhibiting national traits, while later versions employed allegorical embodiments of nations in the abstract. The depiction of national characters frequently served to elaborate national rivalries. Particularly during wartime or on the eve of conflict, the performance of ridiculous national stereotypes permitted the denigration of the countries they represented.22 More fundamentally, though, personifications of nations helped bridge the divide between purely cultural and political conceptualizations of nationality. The materialization of geographical and cultural entities as balletic personas participated in the construction of a political fiction whereby a country personified as an abstract idea or collectivity—rather than in the form of its monarch—might be thought to behave as a sovereign “actor” on the world stage. In this way, ballet modeled ways of thinking about political representation in European diplomacy.

Dances of Delegation

The clearest evidence that ballets engaged with already existing understandings of political representation on the world stage comes from entertainments that featured ambassadors and envoys as their characters. Several ballets of nations use a fictional framework in which characters from distant corners of the globe have traveled to Paris to pay homage to the French monarch on behalf of their countrymen. A few entertainments put greater emphasis on the characters’ identity as ambassadors through verses and staging techniques that invited viewers to reflect on the dynamics of diplomatic representation and delegation.

One example is the comic ballet the Ballet du grand bal de la Douairière de Billebahaut (Ballet of the Grand Ball of the Dowager of Bilbao), staged twice during the Carnival season in 1626, first at the Louvre and then at the Hôtel de Ville in Paris.23 Margaret McGowan has pointed to this ballet as the epitome of burlesque style, as reflected in Daniel Rabel’s engrossing drawings of the costumes and major props. The grotesque figure of the Dowager, in particular—played by a male performer inside a “machine” by court sculptor Bourdin—ridiculed the aging Marguerite de Valois for an in-group of courtly spectators.24 Although critics have examined this ballet’s commentary on the court and its engagement with the Parisian populace, the entertainment’s international theme has received less attention, even though global imagery makes up the majority of the spectacle.25 The ballet featured a series of performances by delegations from the “Four Parts of the World” who, according to the fictional scenario, had come to visit the queen of the ballet’s title. Their exotic garb and accoutrements (including “machine” animals representing the distinctive fauna of each region) surely appealed to the eye and the imaginations of spectators.

But the foreign contingents also alluded to diplomatic delegations. As depicted in Rabel’s drawings, each entrée showcased a small cluster of performers with one lead figure surrounded by an entourage of countrymen: Atabalipa, king of Cusco, led a group of Americans; Mahommet was accompanied by various “peoples of Asia”; the Great Turk ushered in the eunuchs and ladies of his harem; the “peoples of the North” entered behind two Bailiffs of Greenland and Friesland; the Grand Cacique took the stage along with African men and women. Only the “entrée of the Europeans”—a joyfully chaotic performance of Grenadine dancers and guitarists—diverged from the format. The configuration of the continental performances echoed the extraordinary embassies consisting of an official ambassador and several lesser envoys that would be sent to congratulate monarchs on political successes, marriages, or royal births.

The published description and verses for the entertainment further amplified the ballet’s resonances with diplomatic representation. It took as its central conceit that the ballet depicted a kind of courtly summit arranged by the Dowager in celebration of her love for her ridiculous suitor, Fanfan de Sotteville. As the opening pages of the libretto explain: “The rumors which carry on their wings the secrets of the smallest schools as well as the evil plots of the greatest Monarchs, spared not their diligence in spreading among the diverse parts of the World the merits of the DOWAGER of BILBAO; who in order to welcome the virtuous suit of FANFAN de SOTTEVILLE, assembles a great Ball in the manner of her Ancestors, to acknowledge the gestures of her Gallant, and to maintain order among the Foreigners who arrive from every coast.”26 The theme of international renown echoes throughout René Bordier’s libretto in both descriptive passages and verses. Foreign leaders trumpet their own ambition and might: “I make all the Earth tremble, / And constrain the Ocean to revere my Laws,” crows the Great Turk.27 “The earth which burns with passion for me / Gives carte blanche to my ambitions,” boasts the Cacique.28 Armed with hyperbole, they verbally spar for global prestige before praising the supreme merit of their host. While nominally honoring the Dowager, the characters exploit this world stage to enhance their own images and announce their imperial drives, much in the way that the pomp of an extraordinary embassy was designed to burnish the reputation of the monarch who sent it more than the prince who received its tribute.

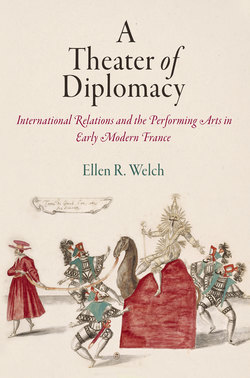

Figure 2. Daniel Rabel, design for the entrée of the “Grand Can” and his entourage, from the Ballet du Grand bal de la Douairière de Billebahaut, 1626. BnF.

At the same time the ballet’s structure mocks diplomatic competition for prestige, it also satirizes the tradition of praise for the host sovereign. The delegates’ fawning addresses to the Dowager work as a parody of contemporary encomiastic ballets that vaunted the renown of the real French king. But the parody grows more complex when verses spoken in the foreign characters’ voices reference Louis XIII’s own glory. Verses written by Claude de l’Estoille for the Great Turk, for example, declare: “It’s only you, Louis the Great, whose weapons shall one day / Fell the Crescent.”29 Explicitly or implicitly, the parade of foreign princes pays homage to two addressees: the ridiculous figure of the Dowager and the real French sovereign, present in the audience. The entertainment simultaneously rehearses and derides the trope of ballets of nations that ventriloquized praise for the king through foreign personas. In this respect, the Grand bal fits Mark Franko’s characterization of burlesque ballet as “a purposive ideological distortion of court ballet’s traditional aims: glorification of the sovereign.”30 At the same time that it embellishes Louis XIII’s stature, it ridicules the forms through which that exaltation takes place.

If the Grand bal resembled a grotesque exaggeration of the competitive representation of prestige occasioned by international summits, the national ballet that formed part of the 1635 Ballet de la Marine (Ballet of the Navy) staged a more direct and profound critique of diplomatic representation. Most of its characters—all of the nationally marked ones—are identified as “ambassadors” in the libretto. The performances of these diplomatic figures bring complexity to an otherwise sycophantic entertainment as the ballet’s script unpacks the political pitfalls of delegation. As the opening pages of the libretto explain, the ballet took as its “subject” the king’s recent political triumphs including the squashing of Huguenot dissent, the clearing away of pirates from the coasts, and the reopening of maritime commerce. Although not explicitly referenced in the preface, France’s new transatlantic settlements in Québec and the Caribbean also helped reinforce France’s reputation for seafaring prowess in this year. This spectacle’s naval theme, moreover, called attention to the accomplishments of its patron, Cardinal Richelieu, who organized the reinforcement of the French fleet and prompted a renewed focus on maritime commerce, particularly in the Levant.31 It also signaled French expansionist ambitions to an international audience through the conduit of the ambassadors in attendance.32

It was France’s recent successes, the ballet text explains, that inspired its characters, in their role as foreign ambassadors, to come Paris to pay tribute to Louis XIII. A brief headnote to the ballet’s libretto explains how its content celebrates French triumph: “The opening of the first part is made up of a song by the Nereids and Marine Gods who come to announce to France the return of her glorious vessels, and the second [part] is drawn from the esteem of foreign Princes who, delighted by the marvels of the greatest Monarch of the world, send to his Majesty, via the mouth of their Ambassadors, assurances of an affection which they swear must be inviolable.”33 Repeating the tributary dynamics of the Grand bal in a serious register, the ballet redirects praise for the king through the foreign mouths of its fictional ambassadors. This intention is repeated in the “récit,” or song that opened the ballet’s second act, performed by the personification of Renommée (Reputation or Fame). Addressing Louis XIII, the figure sings:

Great King, marvel of the world,

I come from the ends of the Universe,

But in all the diverse climates

Of land and of the waves,

I never saw anything that could compare

To the grand actions that make you adored.34

The ten entrées that follow feature dancers playing the part of ambassadors and subjects from foreign nations: Muscovites, Laplanders, Persians, Chinese, and Moors, and at last, following a concert of lute music, pygmies, Giants, “Unknown People” (Incogneues), Amazons, and Americans (specifically, Topinambous, the Brazilian tribe allied with French settlers in Brazil in the mid-sixteenth century). Each ambassador in turn pays versified homage to the French king or to the ladies of the court. The ballet transparently discloses and follows through on its encomiastic design.

Despite its clichéd monarchal praise, the ballet takes a novel, sophisticated approach to presenting its foreign characters. The fact that the figures are identified as ambassadors (rather than simply as Russians, Laplanders, Persians, or Chinese) marks them not as direct embodiments of national characters but as mediators and representatives of political authority. This indirect, and potentially unfaithful, mode of representation comes into focus thanks to the reuse of particular dancers in multiple roles throughout the ballet. The comte de Brion, for example, had already danced as a sailor and as a fisherman when he took the stage as a member of the Moorish delegation. His verses playfully refer to this fact:

O gods! What a sudden change,

What a miracle! What an adventure!

Against the order of nature

I become a Moor in but a moment.35

Similarly, Monsieur de la Trousse, representing a Moor after his prior performances as a sailor and a cannoneer, suggests his newly darkened skin “is but smoke” caused by the flames of love.36 The libretto rhetorically lifts its characters’ masks—or wipes off their blackface—to reveal the dancers beneath the costumes. The verses’ ironic deconstruction of character breaks theatrical illusion and privileges the identity of the performer over the role.37

This staging of performers’ infidelity to their onstage personas carries particular significance in the context of a ballet about ambassadors. As discussed in Chapter 2, the theatrical metaphor for describing an ambassador’s work was controversial in the early decades of the seventeenth century precisely because it called into question a diplomat’s loyalty to his sovereign. For Hotman in particular, what set an ambassador apart from an actor was the fact that an ambassador could not change roles: when one is a diplomat, “one cannot play different characters under different costumes.”38 This anxiety occupies center stage in the Ballet de la Marine as representatives of distant countries declare their readiness to abandon their homes and missions. The Persian ambassador, for example, discloses that he has not undertaken his journeys because the shah ordered him to do so; instead, “I follow all the pleasures where my age conveys me … and if I seem to adore the sun, / It’s because under this beautiful name I revere Sylvie” (that is, his mistress).39 Later in the ballet, the Amazon rhetorically forswears her countrywomen, declaring, “I prefer the Seine to the waters of Thermodon…. and announce here that the love of Alexander / never pleased me so much as that of Louis.”40 In the guise of trite rehearsals of praise for the French monarch, verses such as these give expression to the fictional ambassadors’ individual subjectivity, their private motivations and sentiments, in a way that troubles the conception of diplomats as perfect representatives of their monarchs’ wishes. In the lighthearted ballet, assertions of diplomatic agency pertain to romance rather than Machiavellian political ambition. Still, the ballet discloses the possibility that although ambassadors profess to represent the wishes and intentions of a head of state, they may be performing according to a different script, one of their own or another prince’s devising.

Both the Grand bal and the Ballet de la Marine play with modes of diplomatic representation by ridiculing the kinds of posturing that occurs at international summits or, more deeply, by referencing the problems of fidelity that arise when ambassadors are charged with acting as surrogates for their masters. In both cases, ballet easily appropriated forms of political representation for artistic purposes. The comic resources of the form—particularly burlesque aesthetics—exposed the ridiculous or unstable underside of these types of representationality on which diplomatic practices relied.

Personifying the Body Politic

The Grand bal and the Ballet de la Marine’s critical engagement with concepts of diplomatic representation raises the question of how else the ballet form might have dialogued with theories of political representation. Important studies of Louis XIV’s participation in court entertainments have analyzed how the dancing body of the king reaffirmed royal authority through its charismatic presence (a topic to be taken up in Chapter 6). If monarchal sovereignty is understood to derive from quasi-feudal relationships between the monarch and his nobles (as for Jean Bodin, for example), ballet reflects and reinforces the nature of those ties through stylized reenactments of gestures of subjection. If, however, the monarch functions as a stand-in for his subjects, as a physical incarnation of the body politic, the stakes of his performance change. Famously explicated by Ernst Kantorowicz and based largely on a study of ceremonial practices, this theological view of sovereignty ensured permanent, stable rule through an “uninterrupted line of bodies natural” giving physical form to the mystical “body politic” in perpetuity.41 Distinct from the feudal model of sovereignty, this theory conceives of the king as a personification of the otherwise unrepresentable whole of the polity. Paul Friedland helpfully clarifies: “Political bodies in pre-modern France were not the ultimate objects of the re-presentative process; political bodies were themselves re-presentations. Even for the most die-hard absolutists, the political body of the king was not so much the object of re-presentation as it was a kind of conceptual way station between the political actor and the true object of political re-presentation: the mystical body of the nation or the corpus mysticum.”42 For this reason, in her pioneering work on forms of political representation, Hanna Pitkin groups monarchal representation under the rubric of “symbolic representation” wherein “a political representative is to be understood on the model of a flag representing the nation.”43 As the (mystical) personification of the state, the king also comes to function as a kind of emblem or icon of it.

Turning away from political ceremonies and toward French legal history for insights about the nature of royal power, Tyler Lange suggests that the “juridical fiction” of the king’s two bodies “never emerged quite so clearly in France as in England.”44 In particular, a 1607 edict “prescribed the necessary reunion of the king’s personal and dynastic property with the royal domain,” insisting on “the irrevocable marriage or union of the individual king and his office rather than the distinction between them.”45 Meanwhile, judicial practices before the eighteenth century usually treated courts as “part of the Prince’s body” such that “the inescapably unitary, simple royal person could only either incarnate or be opposed to the nation.”46 Alain Boureau affirms the simplicity and unity of the royal body in France, highlighting both the centrality of the king’s natural body to political rituals and the ubiquity of representations of monarchs as fallible individuals.47 These insights suggest the inadequacy of monarchal representation as a stand-in for the polity as a whole.

In this context, ballets of nations produced new ideas and concepts for theories of political representation. The figures who playfully represent their nations (that is, their people, those who share their ethnicity and territorial roots) do not, of course, have legitimate political power. Yet they do “speak for” their countrymen within the fictional world conjured on the stage. More important, they serve as emblems of their nation, embodying traits stereotypically associated with their compatriots. Those stylized traits take on a symbolic status through performance and re-performance on the stage. In this way, the ballets develop an iconicity of the nation separate from the logic of monarchal representation, making available a new way to envision a collective (geographical, political) entity.

The representability of nationalities emerged and gained iconic force across repeated performances of national stereotypes in different entertainments. Gradually, and with reinforcement from other visual and discursive cultural productions, a repertoire of traits and imagery developed that could instantly indicate the identity of any nationally marked performer: as Ménestrier described, the Turk has his vest, the Americans their costume of feathers. One early example of such national typecasting occurs in the Ballet de Monseigneur le Prince, likely danced in December 1621 in Bourges (perhaps by Henri II de Bourbon-Condé, a prince of the blood residing in Berry).48 The ribald ballet features a series of dances by lovesick “madmen” (fous) who hail from different countries: France, Flanders, the Indies, England, Poland, Germany, Switzerland, Scotland, and Turkey. The costumes and music for this ballet have not survived, but the poetry preserved in the libretto suggests how the figures differentiated themselves according to national traits. Each dancer is assigned a different phallic joke evocative of his national character. The predictably drunken German declares: “I always loved wine above all else, / And a sausage was my God.”49 The Polish fool promises the “Dames” of the audience that his cold humor will not impede their potential courtship: “The cold that reigns in Poland / Moves far away from my members / … Touch my ivory pipe: / All my fires rise from there.”50 Although the characters possess a specific identity (as fools), they distinguish themselves through these national traits and come to stand for a national group by way of iconic resemblance.

The same principle of differentiation structures the first so-titled Ballet des nations scripted by Guillaume Colletet and likely performed in the Carnival season of 1622, before Louis XIII’s departure to suppress Huguenot revolt in La Rochelle.51 This ballet’s characters are all identified as fishermen. But they, too, distinguish themselves from each other by alluding to traits stereotypically associated with their nations: braggadocio for the Spaniard, dancing ability for the Italian, a sturdy build for the German, familiarity with cold weather for the Pole. Distinctive bodily performances reinforced these verbal articulations of difference. Although the music and choreography for this ballet have not survived, clues in the libretto suggest that each figure performed a dance style associated with his nation. The Venetian Pantalone’s reference to the “movement in my buttocks,”52 for example, describes the kind of lively passacaille often used in Italian entrées of ballets of nations, while the German’s allusion to his “strength in the middle of the body” evokes a sturdy allemande dance.53 Distinctive ways of moving and gesturing as well as costume and character traits constituted a performance of nationality that would be recognizable whether embodied by a fool or a fisherman, a king or a clown. In this way, the ballet form allowed a nation—in the sense of a people—to be personified by actors other than the sovereign himself.

Comic, festive, and frivolous, national ballets seem distant from the legal erudition of political theory. Yet theatrical performance offered an important vocabulary for early modern thinkers analyzing and reflecting on modes of political representation. The theatrical metaphor has been most famously used to describe sovereign power in chapter 16 of Hobbes’s Leviathan, “Of Persons, Authors, and Things Personated.” Hobbes here traces the origins of the legal category of personhood to the Latin concept of persona defined as “disguise, or outward appearance of a man, counterfeited on the stage … and from the stage, hath been translated to any representer of speech and action, as well in tribunals, as in theatres. So that a person, is the same as that an actor is.”54 Although historians of political representation often point to his deployment of theatrical vocabulary as original, in fact Hobbes drew from a long tradition that conceived of political power in theatrical terms. Quentin Skinner, for example, shows that Leviathan employed an understanding of political representation as “speaking for” or “acting for” that reached back to patristic authors such as Saint Ambrose and Gregory the Great who, in turn, relied on Cicero’s account of the “role” of public officials in representing the interests of the people.55

Hobbes was not at all alone in understanding that political action only took place through the intermediary of representation. He did, however, provide the most iconic image of representative power in the form of the engraving that served as the frontispiece for Leviathan. Indeed, it has become nearly impossible to address Hobbes’s political theory without reference to this illustration of a large, imperious king whose body is composed of the many, tiny faces of the subjects he represents. The image supports Hobbes’s characterization of the sovereign as a “feigned or artificial person” who gives voice to another’s “words or actions” through surrogation.56 This “artificial person” represents—in the sense of acting for—the will of the multitude.57

One ballet explicitly depicting sovereign representation also elaborates how “artifice” might permit a monarch to represent the will of a people. The Ballet des quatre monarchies chrétiennes (Ballet of the Four Christian Monarchies) resembles a typical ballet of nations except for the fact that each national performance is headed by a “monarch” in the form of a mythological persona. Performed at the Louvre on February 27 and March 6, 1635, the ballet was presented as a thank-you gift from eight-year-old Anne Marie Louise d’Orléans (known as “Mademoiselle”) to Louis XIII after he pardoned her father (the king’s brother), Gaston d’Orléans, for his secret treaty with Spain the previous year.58 As described in a commemorative in-quarto pamphlet, the ballet’s “admirable subject” depicted “Italy conducted by Orpheus, Spain by Juno, Germany by Bacchus, and France by Minerva; each of these Kingdoms having some relationship to the qualities of these four nations that all came to the feet of the noblest king on earth.”59 The librettist draws an interesting distinction between “kingdom” and “nation” in this initial description of the ballet’s conceit. The term “kingdom” (royaume) generally referred to the “governed state,” that is, the territory and people under the command of a monarch. In this instance, however, the word appears in an older and less common usage, as a vernacular equivalent of “regnum” or ruling power. Understood in this sense, “kingdom” refers to the gods and goddesses leading each troupe of dancers, a reading that explains why Germany and Italy are labeled “Monarchies” centuries before those countries existed as unified political entities.

Although the mythological figureheads do not belong to or hail from their nations, the librettist takes care to indicate that they share characteristics with the people they represent. Italy, for example, follows Orpheus, deity of music and poetry. Accompanied by lutenists and singers, the god delivers an opening récit in praise of Louis XIII. In the last verse, he introduces his “subjects,” promising they will pay the king their compliments “in a style as sweet as my voice.”60 The series of performances that follow develops the parallel between Orpheus and Italy by showcasing the nation’s association with music, dance, laughter, and frivolity. “Pleasingly dressed” chestnut roasters dance with such liveliness it seems they “fricasseed their legs” as well as their delicacies.61 Neapolitan “buffoons” and harlequins perform acrobatics and boast about their comedic prowess. Similarly, in the third part of the ballet, Bacchus declares in his récit: “One sees an eternal proof of my power on the banks of the Rhine.”62 The dancers in his entourage incarnate stereotypically inebriated Germans, gamboling joyfully but clumsily in such a way that “they make you burst with laughter.”63 These performances rehearse common French depictions of the Italian and German national characters familiar from countless ballets. In the Ballet des quatre monarchies, though, national traits provide the justification for their representation by a particular mythological ruler. An essential similitude connects the “monarchs” to their subjects.

The role of resemblance in the ballet’s assignment of mythological monarchs to the four Christian nations troubles the assumption that nationality had no relevance to early modern political sovereignty. Often retained within a family and underwritten by divine authority, sovereignty was most often understood as “jurisdictional,” requiring no natural connection between the sovereign and the territory or people he ruled.64 For a thinker such as Jean Bodin, a prince’s usurpation of new territory posed no problem, as sovereignty demonstrated by conquest was sufficient to justify dominion.65 For this reason, on the international stage, monarchs and princes interacted as individuals rather than as “heads of state” understood to be representing the interests, will, or character of their people.66 The Ballet des quatre monarchies, however, challenges the idea that heads of state have a purely imperial relationship to their peoples. Instead, the entertainment plays with the idea that characteristic resemblance strengthens bonds between a sovereign and his or her subjects.

The entrées of Italy, Spain, and Germany rely on symbolism, stereotype, and metonymy to make this claim. The entrée of France presents the most structurally complex version of this vision of sovereignty owing to the identity of the ballet’s performers and spectators. The French subjects need not be represented through the performance of French stereotypes because actual French subjects attended and danced, effectively representing themselves. In the fourth and final part of the ballet, Mademoiselle herself takes the stage as Minerva, France’s own figurehead. The libretto describes her as the epitome of the noble community: “This young marvel … begins to appear in the sparkle and luster of the whole court.”67 The synecdochal connection between the figurehead and the larger group becomes concrete as the entertainment concludes with a ball in which the whole assembly participates.

Throughout the final scenes devoted to the Monarchy of France, the ballet’s framing conceit breaks down to accommodate French political reality. This is especially true in the way the ballet addresses Louis XIII, who participated as a privileged spectator and dedicatee. As Minerva first enters the stage, she rhetorically cedes her authority as fictional “monarch” of France to the true French sovereign off stage. Her entrance is accompanied by the “most beautiful voices and best lutenists of Europe”68 and Mercury, who sings:

Great King, I traverse the skies

As quick as lightning

Carrying the commands of my sovereign Master:

But you know how to imitate him so well

That I can no longer recognize

Which of the two of you is the real Jupiter.69

Mercury’s confusion recalls myths about Jupiter (perhaps especially the story of Amphitryon) that depict him as a shape-shifter who enjoys masquerading as mortal creatures. In a reversal of those tales, though, Mercury represents Louis XIII as the imitator of the god. The verses highlight the French king’s divine right to rule and his supreme power. The comparison to Jupiter lifts him above the lesser mythological “monarchs” whose entrées preceded this part of the ballet.

The staging and rhetoric of these scenes clearly transfer sovereignty from the mythological figure leading the performances of France to the extradiegetic French king. Yet the principle of similitude between the divine head of the entrée and the character of the people she leads remains in place. Although Minerva has been associated with wisdom, music, and the arts, this ballet stresses her relationship to war. She presents a sword and pike to the king as symbols of his valor, as underscored by the accompanying récit:

Most glorious Monarch

Who ever walked the earth,

Just and victorious Prince,

Supporter of laws and honor of war,

The Gods, oh worthy king,

Have they more divine qualities than you?70

Echoing Mercury’s assertion of Louis XIII’s divinity, these verses imbue the king with the virtues Minerva herself embodies.

Although conceived to respond to the delicate reconciliation of Louis XIII and Gaston d’Orléans, the Ballet des quatre monarchies chrétiennes performs additional, more subtle political work in the way it figures sovereignty. It rehearses the reflection on national character typical of the ballet of nations genre, but it also extends that reflection to the person of the monarch, positing that the most appropriate leader or figurehead for a people is one who shares that people’s traits. The ballet implies that embodying the state entails not simply a contractual authorization to “speak for” the populace but also an essential resemblance to it, an ability to incarnate and do justice to its national character.

Staging Interaction

How national cultural traits (such as language or religion) should affect the government of states was a matter of debate in early modern political theory. In particular, early works on international relations considered national character an important concern in organizing the political landscape of Europe. Emeric Crucé’s Le nouveau Cynée (The New Cineas), published in 1623, Sully’s “Grand Design,” published in his Les oeconomies royales, ou mémoires d’État (Royal Economy, or, Memoirs of State) in 1638 but circulated in manuscript form as early as the 1610s, and Hugo Grotius’s De jure belli ac pacis (The Rights of War and Peace), published in Latin in 1625 delved into questions of nationality and sovereignty as they pertained to international cooperation. Most often read as providing the theoretical undergirding for an emergent “society of states” in early modern Europe (a concept to be discussed further in Chapter 5), these texts also challenge the presumption that sovereignty did not necessarily have to respect natural or linguistic borders.

Crucé, for example, argued that ambitious sovereigns trumped up cultural or ethnic rivalries between their subjects and those of their neighbors in order to fuel violent competition for territory. Such antagonism would cease, he contended, if everyone would recognize the meaninglessness of cultural differences between “nations”: “I say that such enmities are merely political, and cannot take away the conjunction that is and must be between men…. Why should I who is French wish ill upon an Englishman, Spaniard, or Indian? I cannot when I consider that they are men like me.”71 If sovereigns would only see the unfoundedness of regional and cultural enmities, perhaps they would limit the extent of their ambitions, content themselves within the borders of their existing dominions, and all of Europe could benefit from the peace and prosperity that would follow.72