Читать книгу Siobhan's Miracle - They Told Us She Had Weeks to Live. Then the Most Amazing Miracle Happened - Ellen & Derek Jameson - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

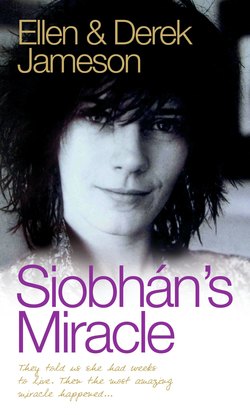

SIOBHÁN’S STORY: WE’LL MEET AGAIN

ОглавлениеOn 5 May 1999 I closed and locked the door of my office in the Literature Department of the University of Sussex, nestling beneath the hills of the South Downs.

The day was warm and sunny as I set off across campus to walk the five miles to Brighton railway station by way of the seafront. It was 1991 and I’d taken up the post of lecturer at this most modern and radical of universities after eight years in America as student and then teacher.

My head was filled with observations on the work of students already seen that day and I made a mental note of work to be discussed with those pupils whose tutorials I had hastily rearranged.

Mentally I also ran through the research needed for an upcoming guest lecture and wondered if I’d left behind any important papers or reference books in my rush to leave the building.

Certainly I’d left my outdoor coat and a small overnight bag, deciding that I already had more than enough to carry. My briefcase was, as usual, filled to bursting with paperwork, publications and unmarked essays.

There was no way of knowing that more than a year later I would still not have returned to my paper-strewn desk in that office with its sign on the door ‘Professor Siobhán Kilfeather, Lecturer, English Literature’.

Sitting on the train from Paddington to Shrewsbury on the way home to our cottage in Shropshire, some 220 miles from Brighton, I replayed in my head the previous evening’s telephone conversation with my husband Peter. He was at home with our two children, Constance, who was four, and Oscar, who was coming up to two. I had carefully timed my phone call till after the children were in bed and the Manchester United game against Liverpool had finished on Match of the Day.

Peter was depressed. He couldn’t disguise it, though he was making a real effort to sound normal. At the time I thought, ‘If this is how he reacts to a disappointing football score, what will he feel like if the results of my tests are positive? He’s getting things a bit out of proportion.’ But in my heart of hearts I knew the reason.

‘Why won’t you tell me what’s wrong?’ I asked yet again. The only explanation I could force out of him just didn’t ring true. He tried to make me believe that his upset was because Paul Ince had scored an equaliser against Manchester United in a 2–2 draw. But I knew my husband too well. The unspoken message in his voice was stirring up in me a feeling of impending doom.

‘Expect me home tomorrow,’ I said quickly. Already I was visualising changes I would need to make in my schedule. Peter wouldn’t admit it but I knew instinctively that he had received the results of a biopsy I had undergone a month earlier at a local hospital at Stoke.

His voice told me what he refused to put into words. The test was positive. I had cancer.

All the way home my mind refused to let go of the word ‘cancer’. I tried to escape into the make-believe world of books – always my escape from the real world – but my mind refused to concentrate.

The motion of the train seemed to echo my thoughts: Living with cancer, dying from cancer, living with cancer, dying from cancer…

It was close to midnight before I drove down the dark and narrow lane to our home, a mile above a cross-country road outside Shrewsbury.

Peter’s face was etched with pain and worry, but still he tried to distract me from hearing the bad news. He claimed tiredness – trying to put off for just one more day the stark fact that we were staring into the unknown. Our lives were about to change irrevocably.

‘Let’s deal with it in the morning,’ he said.

However, I was not to be put off – the suspense was agonising.

Knowing that I would be difficult to contact during classes at the university, I had instructed the hospital to leave a message on the answering machine.

‘Let me hear the message, right now,’ I demanded.

But Peter had already wiped the tape clean. As if by erasing the message he could erase the truth.

Finally, close to tears and as the clock struck midnight, he gave me the bad news: ‘The results are positive. You have to go straight away and see Dr Edmunds at North Staffordshire Hospital. Tomorrow.’

Climbing the stairs to bed, I looked in on our two children, sleeping peacefully. They could not know that their mother’s life, and inevitably theirs too, was about to spin out of all our control. We could not begin to fathom what would happen next.

That night in bed I clung to Peter, who lay rigid with fear beside me. Each time I tried to close my eyes I was tormented with feelings of stark terror.

Neither of us slept a wink all night.

Still the refrain in my head: Living with cancer, dying from cancer, living with cancer, dying from cancer.

My body had been invaded – I had cancer.

The nightmare had started back in 1997 when I was pregnant with my second baby. I went to my GP in Shropshire and told him that I had a mole on my back that worried me. I thought it might be cancerous. I’d read the leaflets in the surgery and it seemed to me that I had the symptoms of malignant melanoma.

He said, ‘No, no, no, it’s only a mole. You’ve been reading too many women’s magazines.’

All the same, it was bothering me, I said, and suggested I should arrange to have it removed privately, but he said he would refer me to a local hospital in Stoke to have it removed on the NHS.

I was still waiting eighteen months later and when I went back to the surgery to check whether the referral had gone through, another doctor looked at my records on the computer and told me to go straight to hospital that day.

It was as if someone had punched me in the stomach. There was no delay this time and I knew then it must be pretty serious and could be skin cancer.

The biopsy was performed at Shrewsbury Hospital and the surgeon told me there was a fifty–fifty chance that it was malignant. That was the first real indication of a major crisis. The word ‘malignant’ was used rather than ‘cancer’.

After the hospital appointment I made my way to my husband’s office in Shrewsbury and he took me to lunch at the local fish and chip shop. Not surprisingly perhaps, my usual healthy appetite had deserted me and I couldn’t eat a thing. Peter was worried, though it didn’t stop him clearing his plate. Over our meal I told him that I thought the growth was malignant.

Knowing that doctors are not in the business of scaring you, I thought if he said fifty–fifty there was a good chance it was actually ninety–ten.

That was in late April 1999, just before the May bank holiday, and the four of us had rented the village hall where we had held Constance’s birthday party a few weeks before. We had taken it over again to bounce around on the trampoline and play with toys that were too big to be used in our house because work was going on building an extension and conservatory.

The test results would probably come at the end of that weekend and I thought, ‘What if this is the last carefree weekend of my entire life?’

My mind was filled with thoughts of how much I loved Peter and how lucky I was to have the children. I worried for all of them and wondered what it would mean to their lives if the mole had become malignant.

One of the worst times was when a dermatologist came to see me in my home. He told me the depth of the disease and said it was the worst case of malignant melanoma he had ever seen.

I put it to him straight: ‘Am I going to die?’

His answer was to ask: ‘Are you a religious person?’

I was so shocked that I just fainted away. I was standing up and he had to pick me up off the floor.

I finally managed: ‘If I’m going to die, how long do you think I’ve got?’ He turned his face away from me and didn’t answer.

My mind went into overdrive after he’d gone. If I’ve got three or four months, I should try and finish my contribution to The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, a monumental work I’d been involved with for several years.

My head is so full of clutter I can’t think straight. I should write to old friends I’ve lost touch with. Tell them I’m going to die.

I can’t seem to get things into proportion. The most important considerations are obviously my children and my husband, but also my work is important to me. My writing, my book, my students.

Should I spend the last twelve hours of my life reading Jane Austen or writing an essay or singing nursery rhymes to my children ?

The first operation was in North Staffordshire Hospital in Stoke. The surgeon had made one wide incision on my back, taking off a wide deep area of skin about six inches square where the original melanoma had struck. Some weeks later, another wide incision, though on a smaller area of my knee for a suspected melanoma which turned out to be non-malignant.

In the same hospital I underwent reconstructive surgery. They removed a large area of skin from my thigh and grafted it on to my back. This operation was not a success. Would they do it again?

At that time the next treatment was scheduled to be a course of chemotherapy along with Interferon and possibly an experimental drug treatment.

In January 2000 I reported to the Royal Marsden Hospital in London for post-operative treatment after my surgery in Stoke. I was confident I would be given the all-clear – the cancer seemed to be in remission and I’d never felt better.

Instead they dropped a bombshell – I now had secondary cancer and it had already spread to my lungs. I was in a state of shock.

Somehow a strange feeling of invincibility had convinced me that I would never have to face such devastating news. Now I replayed the conversation and the words the doctor had used again and again in my head: ‘Secondaries – lung cancer – very serious.’

They told me that chemotherapy was the only course of action. I would have to undergo a particularly aggressive treatment – they admitted they wouldn’t have tried the procedure on anyone who wasn’t young and fit. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

For most of the past year I had been taking part in clinical trials for a new form of non-invasive treatment based on a combination of drugs. Now I would need four weeks to allow these chemicals to be flushed from my system before the chemotherapy could be started.

I went home and began to put my affairs in order. There was a lot to be organised regarding the children, Oscar’s nursery and Constance’s school, as well as arrangements for someone to look after them while I was in hospital. Initially it was to be a period of five to seven days in hospital undergoing the chemotherapy and then two or three weeks at home before a second and possibly a third stay as an in-patient.

A review would be made after the second course of treatment around the end of March. If the results were not encouraging, it might be decided not to proceed with a third round of chemotherapy. At that stage no one could say what the effects or the results would be – but they were willing to try.

No one was quoting odds on the treatment working but I was reassured even by the fact that they were prepared to give me it at all.

As part of my regular on-going treatment to relieve stress, once a week I went for a massage. I had not been able to lie comfortably on my back because I got that sensation of panicking and not being able to breathe. These may have been normal symptoms of lung cancer but they might just as easily have been caused by hypertension and anxiety.

For a couple of months now I had also suffered from back pain. I also had to contend with pains around the groin and the abdomen. I wouldn’t be surprised if those were areas where I did now have cancer, though of course they could be anxiety-related.

Some of these symptoms I described to a wonderful South African doctor at North Staffordshire Hospital, Mr Prinsloo, together with a catalogue of other totally unrelated symptoms. I went in to see him some months previously complaining of earache, which I thought was a symptom of a brain tumour. He quickly disabused me of that idea. ‘Earache is not a symptom of brain tumour,’ he told me. ‘I’ve no intention of telling you what is because you’ll start to develop those symptoms.’

There was also the time when I rang the cancer clinic at the Royal Marsden complaining of blood in my stools. It turned out to be an excess of beetroot juice, which I had been drinking as part of my healthy high-vegetable diet.

On another occasion Mr Prinsloo told me that he thought the melanoma on my knee was cancerous and he had decided to send a sample to the laboratory for testing. I told him I knew it was cancerous because I could feel the cancer coursing through my veins. ‘What you’re feeling coursing through your veins is adrenalin,’ he assured me. ‘You don’t feel cancer coursing through your veins.’

It’s very difficult to talk about symptoms at this stage because every ache and pain felt like cancer to me. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the past year had been like a waking nightmare.

Night-time was worst. I lay awake in a cold sweat clinging to Peter. The fear of dying made me feel desperate and almost demented. The way I have survived this phase is chiefly with the help of antidepressants.

But you can’t go on like that for ever and with the passage of time I needed to refocus. This was possible largely through the advice and help of Mr Prinsloo. He put it on the line: ‘None of us know when we are going to die. Think about what you are going to do with your living. You could walk out of this hospital today and be run over by a bus. Try not to let the fear of death overcome what it is you want to do with the rest of your life.’