Читать книгу Ellery Queen's Japanese Golden Dozen - Ellery Queen - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

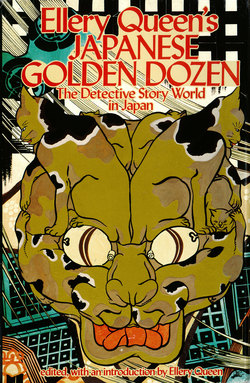

ОглавлениеEITARO ISHIZAWA

Too Much

About Too Many

Eitaro Ishizawa was born in Manchuria and began to write detective stories in 1963. He is noted for his ingenuity and for the wide range of his source material, which includes art, biology, history, and archeology. Although he has published relatively jew books so jar, each one is a fine work written with carefully developed plot and ideas,

His story in the Japanese Golden Dozen introduces Police Inspector Kono in the case of a murder that occurred on Friday the 13th during an end-of-year party—a murder with 13 witnesses. The victim is a good man, respected and trusted, the soul of discretion, the Father Confessor of the 13 suspects—not at all the sort of man who kills or is killed. A baffling mystery—but Inspector Kono is a cool; patient criminologist. . . .

WHEN Police Inspector Kono got into the car in F, where the prefectural capital was located, he said to himself, "This case will drag on for a long time."

Since the war, scientific investigation had become the byword of the police world. Mention of such things as the sixth sense was avoided. Still, Kono knew that what was called intuition was really the result of many years' accumulated experience. Though he did not oppose the principle of system, which condemns putting too much emphasis on experience, Kono knew that intuition was at work in a police investigation.

Officer Satohara had come in the car to meet Kono from the local police branch office in S Spa, where the incident had occurred. Kono asked him, "Where'd they set up investigation headquarters?"

He meant the headquarters that had been established for investigation of the murder of Taro Usami.

Satohara gripped the wheel firmly. "They've rented a house not far from the Happiness Inn."

"A house, eh?"

"Yeah. The garden house of a local rich man named Sakai."

"That's real nice."

The death had taken place at the inn. It was impossible to set up investigations in a commercial lodging, and the local police office in S Spa was too small. Happily, they found a suitable place to investigate a murder that had ironically occurred in a place called Happiness Inn.

Officer Satohara said, "Chief Takahashi's eager to see you."

"Oh?"

If Satohara's words had been uttered by an experienced detective, they might have been taken for gross flattery that could only be ignored. But Kono glanced at Satohara's childish, tense face in the rearview mirror and thought how it could only be maybe two years since this young man was appointed a police officer. He had probably gone into police school immediately after graduating from high school and had been in a front-line police office now for no more than eighteen months. Innocently, he probably believed and tried to practice the motto that police exist for the sake of citizens and swallowed everything his seniors told him. In fact, he likely deified his seniors and had a dazzling image of Kono. Kono judged these things from the stiffness of movements and the flushed color of the young man's face.

"How d'you like working in a police branch office?"

"Very interesting. I mean, I enjoy my work."

"That's real nice."

Trying to use soft words to relax Satohara, Kono recalled what Chief Inspector Kimura had said to him that morning. Depending on how they were taken, his words, too, could be regarded as flattery. Kimura told Kono that he was sending him to act as assistant head inspector in the case of the death of Taro Usami, which had taken place the night before. "The boys down there figure the case is solved once you've been assigned to it. Especially, Takahashi. I guess it's a case of leaving anything connected with big business to you. Do your best."

There are two ways of using people: cajolery and pressure. Kimura adopted the first. His policy was to praise.

But Kimura did not make up the part about big business, and the inference to Kana's aptitude. Kono enjoyed this reputation throughout the entire group in the prefectural department. It was said that in a hundred percent of all cases, if a murder involved the internal conditions of some business concern, Kono would find who did it.

Kono had a long career in the second department, which dealt with corruption, fraud, and similar offenses and which handled cases connected with government organs and commercial enterprises. A man in charge of this department for ten years has no choice but to become a specialist in company organizations and the mental attitudes and reactions of executives and employees. Kono had been transferred to the first department, handling homicide cases, four years ago. His long experience in the second department stood him in good stead. Aside from spontaneous killings, murders taking place within companies often bore connections with grudges and ill will. Kana's knowledge of the inside and outside of white-collar workers' minds was valuable.

It was nine in the morning when the car pulled out of the city of F and headed for S Spa. The police car was caught in the heavy traffic of the rush hour. This gave Kono time to think about the death of Taro Usami. From Kimura, Kono knew the general outline of the case. But he thought, "Still, they've acted fast."

The incident had occurred at nine thirty, Friday night, December 13. Chief Takahashi of the S branch office had set up investigation headquarters at eight the next morning. This was fast work, in spite of the close communications maintained with prefectural headquarters.

Kono regarded the chief's action as especially astute, because it required courage to determine whether death had been murder or suicide in cases of this kind. On the other hand, he had misgivings about hasty judgment.

The facts were simple. The general business office of the Sanei Electrical Thermal Engineering Company, located in the city of F, had been holding an end-of-year party in the main room of the Happiness Inn at S Spa. Thirteen staff members and the company managing director attended. It was the right time of year for such a party: employees had received their bonuses only five days earlier.

The party began at seven and reached a peak by nine. Formalities were set aside in the generally relaxed mood. Though the S Spa is only thirty minutes from the city, most of the men decided to spend the night. Word had it that the waitresses in the hotels and hostesses in bars in this resort town would sleep with customers for low rates.

Suddenly, Taro Usami, head of the personnel department, showed signs of acute suffering and was dead in five minutes. A great commotion followed.

Chief Takahashi was called at once. He immediately initiated investigations by questioning thirteen witnesses.

In questioning, he determined that death had been murder and that the employees in the inn kitchen were not" responsible. He made contact with prefectural headquarters and set up local headquarters for the investigation of the murder. The direct cause of death had been a highball containing potassium cyanide. Usami had only one more year before retirement.

"Fast work," Kono thought. It took courage to decide the killer was one of the thirteen other participants at the party. Kono believed the solution to a case often depended on the speed of initial investigation and quick decision on whether the death was accidental or murder. But for some reason, when he got into the car that morning, he had the notion the case would drag on for a long time.

He recalled a case in which he had stumbled years ago. He had been on the force only seven years, and had just been made an assistant police inspector. Immediately after promotion he had been lax, and this case developed. It was an instance of youthful error. Thanks to the warm help of his superior, Inspector Takami, the matter concluded without serious consequences. But even now, thinking about it, he broke into a cold sweat.

"It's stupid," he muttered, shaking his head to rid himself of the mean memory.

The car pulled into S Spa. Kono saw the sign on the door of the rented private house: "Investigation Headquarters."

2

Kono sensed a fever of activity as he stepped into the entrance hall. Inspector Takahashi greeted him. They had met before. Still, being met personally by the man in charge gave him a heavy awareness of what the staff expected of him.

"We're running through secondary inquiries, right now," Takahashi said quickly, leading Kono into a small room next to the entrance hall. He told him the general results of the first inquiries. Nodding, Kono said from time to time, "I see," and "Oh, really?"

What Takahashi had to say boiled down to two main points. First, Taro Usami was not the type person that anyone in the company would resent or hold a grudge against. Second, each of the other thirteen people in the room at the time had had a chance to pop the potassium cyanide into Usami's highball.

"The party began at seven. By nine thirty, nobody was feeling any pain. None can recall when Usami drank the drink. That gets me."

"Who made the drink?"

"Well, there's a shortage of waitresses. So these people did a kind of self-service. They all brought bottles and put 'em in one corner of the room. Anybody who wanted a drink helped himself."

"I see."

"But what worries me is Usami's personality. Everybody praised him. I don't think they're lying, either. They really liked him. I can't lay my hands on a motive." He made a face. "But, you know, that company's really piling up loot. I was surprised to hear how much bonus they pay. The bonus of an office girl at Sanei is equal to mine."

"Yeah. An interesting company."

"You know something about it?"

"A little. Seven years ago, there was a case of corruption in the local city office. Sparks flew around Sanei. I ran an internal check on 'em."

"You really know your companies, don't you?"

Kono realized he knew more about Sanei than anybody else on the police. After all, it was a firm he'd had his eyes on since his days in the second department. His remark that Sanei was an interesting company reflected experience and knowledge.

Sanei belonged to a contradictory business type, frequent among companies having demonstrated rapid economic growth, in which business is very good but the company unstable. It paid good dividends and still had a sound internal reserve. The cancer eating away at the company and making it unstable was a two-cause result: strife and factionalism among the executives and conflicts on the labor-union front. On two occasions in five years, presidents and managing directors had been dramatically forced out. Not many companies have such a tempestuous domestic life. Within the sixty staff members, there were two labor unions, each violently opposed to the other.

The major cause of this situation was the nature of the company itself. It had been formed fifteen years earlier by ten small electrical companies who were just beginning to develop. Each company came equipped with its own set of executives and labor unions. Labor unions tend to split up in companies that are new and lack tradition. There seemed no hope of compromise between the two groups at Sanei. The first union called the second the Establishment, and the second criticized the first for being radicals. It was only the steady supply of outstanding, independent technicians, attracted by high salaries, who worked for the company that enabled Sanei to show good business results.

Kono knew these details because of his experience with the second department.

Takahashi said, "Come, sit in on the second interrogation."

"O.K." Kono followed Takahashi from the room.

The purpose of the second questioning was to track down discrepancies in testimony given at the first, which had taken place from two to ten in the morning.

Kono glanced over the brief history of Taro Usami and the list of thirteen suspects that Takahashi had given him. He then read the history of Taro Usami with special care. There were too many names on the list.for him to form any images without personal meetings. Still, he made mental notes of some of their vital statistics:

Managing Director, Kenzo Yokomizo, age 58, 5 years in firm.

Business Bureau Chief, Yozo Misumi, 40, 5 years with firm.

Business Department Chief, Akira Atsuta, 33, 4 years in firm.

Saburo Matsushita, 29, 5 years with firm.

Shinkichi Harada, 28, 2 years with Sanei.

Yoshio Ozaki, 28, also 2 years.

Haruko Nagai, 28, 2 years with firm.

Personnel Department staff:

Shiro Shibaura, 31, 5 years with firm.

Yuzo Nakanishi, 31, 5 years in firm.

Junichi Murayama, 29, 2 years.

Tetsu Nakajima, 26, 1 year.

Yasuko lkenami, 25, 1 year.

And typist, Yumiko Murase, 33, 5 years with firm.

3

One by one, each of the thirteen was summoned from the Happiness Inn, not far away. They were subjected to penetrating questioning. Some seemed nervous, others quite calm. As Kono listened, Taro Usami, the victim, was the thing most firmly fixed in his mind. He believed that, without a clear understanding of the victim's authority and place in the company and of his personality, it was impossible to form an image of the murderer. Whenever he asked a question, it invariably pertained to Usami.

To Kenzo Yokomizo: "Mr. Usami was with the company for ten years, longer than any of you. He was a college graduate. Can you suggest any reason for his slow rise in the firm?"

To Yozo Misumi: "Mr. Usami was the head of the personnel department for seven years. Why did he remain in this position so long?"

To Akira Atsuta: "Was Mr. Usami popular among the technicians?"

To Saburo Matsushita: "Did Mr. Usami seem to favor one or the other of the two labor unions?"

To Yumiko Murase: "Was Mr. Usami popular with the women employees?"

From the answers to such questions, Kono developed a clear image of Usami's personality and learned why, in spite of new executive staffs every five years, Usami had not moved from the position of chief of the personnel department. Of others who had entered the company at the same time as Usami, not one person remained. Many had been forced to leave as a consequence of becoming enmeshed in the factions surrounding the executive positions. Throughout all this turmoil, Usami had persisted in being neutral: See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.

Why should someone who tried to remain unbiased and fair in all things fail to advance? A company was a living thing with an elaborate interweaving of subtle emotions. The man who tried to remain in the neutral position in conflicts was disliked by both sides. He was labeled unreliable. He could even be thought a double-dealer or timeserver. Though not forced to leave the company with the followers of the defeated executive team, he was not regarded seriously by the winning group. Because of conditions of this kind, Usami had remained the head of the personnel department. There was nothing to indicate whether Usami adopted this policy of neutrality out of principle or for utilitarian reasons.

But it was part of his personality, or so it seemed. He had entered Sanei Thermal Engineering at forty-five. For twenty years before that, he had been a white-collar worker for another firm. Thirty years of work in business probably made it a habit to want peace at any price. As simple proof, Kono pointed out to himself Usami's office nickname: the Quiet Man.

Although slow to speak, Usami had not been narrowminded. This was suggested by his willingness to listen to anybody's complaints, dissatisfactions, secrets. People often carried their griefs to him because they knew they were safe in telling Usami. The Quiet Man would never repeat anything he heard to a third party. Kono was strongly impressed with this aspect during questioning.

Kenzo Yokomizo said, "I trusted him entirely. He was the closest-mouthed man I've ever known."

Shinkichi Harada said, "It's not so much that I relied on him. But he'd listen to any complaint no matter what. Often, I met him on the way home, talked, and got what was troubling me off my chest. He was completely good."

Haruko Nagi remembered him fondly. "Oh, in that sense, you could trust him entirely. Mr. Usami'd never repeat anything you told him."

But there were others who were critical. For instance, Yuzo Nakanishi said, "Oh, sure, he'd listen to you. But he never suggested anything, or gave advice. He'd just sit and listen. In that sense, you couldn't rely on him. But since most people already have an answer to their problem before they tell anybody about it, they're generally content to have a listening partner. Even if you criticized the top execs, you knew you were safe talking with Usami." Though he made the comment that it was not possible, in a sense, to rely on Usami, he ended by praising him.

A man to whom everyone told his troubles. A man everybody trusted, because he would not betray them. Is this the kind of man that gets murdered?

Chief Takahashi decided it. was murder. He did so on the basis of Usami's attitude displayed until he began suffering from the poison. A person intending to kill himself usually reveals excitement of one kind or another. Everybody said Usami had been enjoying drinking. This was not the nature of a suicide. The high opinion held of Usami flustered Takahashi. The investigation team noted this.

By four that afternoon, all employees of Sanei had returned to their homes.

In a scholarly tone, but with a certain excitement, Chief Takahashi said, "Usami's family life was peaceful and content. He had no outstanding debts. His hobby was the inexpensive one of gardening. He was liked by his neighbors. In other words, he was a fine member of society about whom nobody had anything bad to say. I know of only one case of murder like this."

"What's that?" Assistant Inspector Iizuka asked, with a look of disbelief. The other members of the investigation team shared this look.

"It's in my imagination. Somebody in the company tells Usami an important secret. Later, he thinks, 'I've done it, now. If Usami spills that, it's all up with me.' Then this guy gets the idea of killing Usami. . . ."

One of the team objected. "But Usami was famous for keeping secrets."

"Yes. But if the secret was very important, the person who told it might become the victim of terrible doubts," Kono said, thinking that Takahashi had something.

Another of the team said, "I can't help thinking the police chief's explanation relies too much on imagination."

There was some substantiation to this objection. Takahashi, disgruntled, said no more. An uncomfortable silence ensued.

Could it have been suicide? Kono felt this doubt among the members of the group. No one voiced it. They had investigated the case as murder to this point.

Pressure of duties had made administrative employees kill themselves. Often these suicides paid no attention to their surroundings. During rush hour, they leaped in front of oncoming trains, or hurled themselves from office windows during work hours. Usami might fit this category.

A veteran detective named Hosobe, asked, "Chief, couldn't it be suicide?" It was a brave gesture under the circumstances. Kono had heard that Takahashi and Hosobe did not get along well.

Takahashi said clearly, "Right now, I'm not considering suicide. In the first place, there's nothing in Usami's daily life to warrant suicide. In the second place, potassium cyanide looks like a planned killing. There was no suicide note. And, two days before the party, Usami himself bought plane tickets for a business trip to Tokyo."

"I see." Hosobe seemed convinced for the moment. The investigation was ploughing ahead for murder, and Hosobe lacked sufficient confidence to try to call it to a halt.

Turning to Kono, Takahashi said, "How d'you make it?"

"You mean murder or suicide?"

"Yeah."

Kono folded his arms. "I think the chief's right. It seems like it's murder. Forgive me for being vague."

Takahashi asked, "I get the feeling the investigation's bogged down in questioning. What d'you say?"

"Earlier, you said everybody was prepared for Usami to keep their secrets. Maybe it's related to the heart of the matter. I'm not saying it points directly to a conclusion, but it might be a good notion to examine the issue from the viewpoint of what's happened in the company." Kono glanced around, scowling, then said, "Right now, the idea of self-defense is especially strong in commercial enterprises and their staffs. To give a simple example—a bank where embezzlement's occurred. It's possible to make preparations. Let's say the amount is five million yen. The bank will certainly deal with this within the limits of its own organization and not let word leak to the outside. After all, banks require the customers' trust. If Usami'd heard an important company secret—and if this is the cause from which the crime grew, the investigation. . ." Kono paused. Then he slowly added, "Will be very difficult."

One of the investigation team had come in and was whispering something to Takahashi. Wrinkling his forehead, Takahashi said, "The lab report says the only clear prints on the glass are Usami's. There are other smears, can't be identified. Another thing, potassium cyanide is used by Sanei. Strictly controlled, but an employee could probably get it if he wanted it bad enough."

The room was heavy with silence.

That night, Kono found it difficult to sleep. His mind was busy with the Usami case. His intuition told him it was murder. But he was convinced some secret was concealed behind the matter. He had talked of self-defense in commercial enterprises and their staffs. He'd given a bank as an example. But cases like this were not limited to banks. They could be found in the police department itself. Instances of embezzling occurred in the police and were dealt with without publicity. The police, too, required the trust of the people. While uncovering crime, they had to eliminate such from within their own ranks. Kono recalled the mistake he'd made in his youth. It embarrassed him to think of it, though it could not really be called a crime. . . .

Just promoted to assistant inspector, he went through a brief period when he lowered his standards slightly. As the person in charge of economics-related crime, he had to deal with illegal practices in horse and bicycle racing. This meant he often traveled to the tracks. One day—he must have been bewitched—he suddenly found he'd bought bets on a race and that he'd made a large winning. Although he realized it could be the start of involvement with other kinds of gambling, he began taking a lively interest in horse races and bicycle races. There was no rule that a policeman must not gamble. But there was an unwritten law that they should exercise self-control. Because he had a guilty conscience, Kono avoided the tracks in F city and attended regional ones.

One day, when he had lost all the money he'd brought with him, he felt someone tapping his shoulder. Turning, he saw Wakamoto, the head of a small loan-company.

"The afternoon race is the big one," he said casually. "Want me to let you have some money?"

Wakamoto had noticed that Kono's funds had run out.

"Maybe—"

This was his mistake. Once this kind of borrowing starts, it becomes habit and debts snowball. A policeman is the best kind of customer a small loan-shark can have. Because of his work, he cannot kick back. Before Kono knew it, he had borrowed more than he could pay off. Interest piled up, and the debt increased. He knew he must do something. The days rolled relentlessly by.

One day, his superior, Inspector Takami, called him. The two went to an out-of-the-way restaurant. Seated, Takami said, "I consider you a talented man. Your promotion to assistant inspector was the fastest in the department, ever. It makes me proud of you. But you've got into debt, right?"

"What?"

"You're dealing with a nasty customer. Wakamoto's tied up with gang financing."

The blood drained from Kono's face. Takami knew everything.

"How much can you scrape up from friends and relatives?"

The conversation swept on, and Kono was powerless to resist. After all stones were turned, Kono was still short one million yen. Takami lent it to him out of his own pocket, saving him from a bad predicament. Kono considered Takami a great benefactor from that time on.

Takami had happened to spot Kono's name in Wakamoto's books when he was making a check. His foresight saved Kono from a serious black mark, both in and out of the police force. He'd certainly have been disgraced if he'd been publicly exposed in the books of a petty loan-shark.

Kono learned from the mistake. First, he gained a true understanding of what it meant to be a policeman. Second, he saw the police as an organization that acted speedily to cover whatever unfortunate events occurred within its limits. Kono realized that Takami had also taken the step to protect his own position as a ranking officer on the force. Unreliable people in the department would have brought a black mark against him as well.

Since then, Kono had been so severe on ethical points that he'd earned the nickname, the Hard Guy. His mistake proved a good tonic that later brought him immense trust. He had to grow to the point where he could take a cool, professional look at everything happening above him in the organization. Kono understood the self-defense syndrome in big business. He suspected Taro Usami's death was connected in some way with the self-defense feelings of the company or someone on its staff. A sense of smell developed through years of experience led him to this belief. Difficulty in falling asleep, because of the Usami case, was shared with Kono by all thirteen of the people who had been questioned.

Kenzo Yokomizo was wide awake. "I didn't lie. That's certain. It's just that I didn't volunteer information on some things. Still. . ." He tossed, turned. "Why'd I shoot my mouth off about a secret to Usami? I knew what he said wouldn't do any good. He had no talent. He wasn't forceful. All he did was work hard. But, whenever I was alone with him, I always wanted to talk. Must've been because I knew he'd never tell what I said. That day, on the way home from work, I met him—invited him to a restaurant, and after a few drinks, started talking."

"Promise not to tell anybody, but. . ."

A month before, representatives of the large electrical firm K had held a secret discussion with Yokomizo. It was a sounding out on the subject of merger. The K company was weak in the heating and air-conditioning department and had its eye on Sanei's outstanding technical staff.

K Company, knowing that Kiyose, the president of Sanei, hated the idea of big firms, put feelers out to Yokomizo. Terms were good. For bait they offered him a director's chair. Obviously, he took the bait. He was already at a deadlock with Kiyose anyway.

Their strategy demanded secrecy. Using an affiliate's name, the K company would buy up miscellaneous Sanei shares. Then, at a general stockholders' meeting, they would demand the resignation of President Kiyose, work out something to conciliate the executive staff, etc. This project was already deeply, silently underway.

Yokomizo bit his lip. Why had he let Usami in on such an important secret? Of course, he couldn't tell anyone about the letter he'd received from Usami on the eighth, about what he'd done to comply with that letter. If he let that out, he would become an important suspect in the Usami murder.

A sleepless night visited Yozo Misumi: "Usami was probably murdered, but I didn't kill him. But why—why did I tell him about that?"

The whole affair had ended in four months. It was only a game for her, a way to work out her frustrations because her diabetic husband couldn't satisfy her. It wasn't the first time Misumi had been to bed with another man's wife. But all the other affairs had ended with nobody the wiser. If this one should be known, it would be fatal for Misumi. He had picked the wrong woman.

That day, driving down a busy street, he glanced out the window and saw a woman wave to him.

"Give you a lift?" he asked. She was carrying a shopping bag.

"That's great."

"Get in, then."

She did, then said, "Why, it's not even three o'clock." She smiled. "On a day like this, I bet the country air's fresh and clean." When he thought back, Misumi knew what a clever invitation it had been.

"Why not drive out to the Cape?" he said.

"What about your work?"

"Conference just ended. It's O.K.," he said, turning the wheel.

"I hear you're real cool with the girls."

He said nothing.

"My husband told me."

Then, the conversation took a softer turn.

Many of the men said she was too good for her old man. As the rumors suggested, she had a youthful, fresh body.

Misumi thought he would never tell. The only person who had known she was Shigeko Kiyose, the wife of the company president, was Taro Usami. He knew because Misumi told him.

He no longer had anything to do with her. When they passed on the street they pretended not to know each other. Still, though it was all over, if it were ever discovered. . . After all, she was the president's wife. This meant the issue wouldn't be settled on the basis of individual privacy alone. He certainly couldn't tell anyone about the letter—dated the eighth—that he'd received from Usami. If that got out, he would be a suspect in a murder case.

Saburo Matsushita, of the business staff, had an introspective personality. His reflective thinking tended to be gloomy. He, too, suffered because he'd told Usami something he should never have mentioned.

"It's tragic. . . ." That was how he started; then he told Usami everything.

Matsushita had homosexual tendencies. It wasn't that he was completely uninterested in women. He swung both ways. But, if his ideal type man appeared, that was a strong magnet, and he was iron filings.

"My trouble's I'm not attracted to gay men. They turn me off. For me, a man has to be normal. What does this mean? No sex. Because normal men find gays repulsive.

"But my ideal has turned up. Promise not to tell this to anyone, but it's the head of the business department, Akira Atsuta. He's a sportsman, efficient and good at his work. He's my ideal. But how's this for irony? He wants me to marry his niece. Of course, I'll marry her. That way I'll have him with me always, as a relative."

Matsushita berated himself. Why had he made such a personal confession to a department head—the head of the personnel department, at that. And the wedding was scheduled for the following spring! Then, there was that confidential letter from Usami, dated the eighth.

Sometimes Matsushita had wanted to kill Usami. Then Usami died. The thought that he had for a moment wished his death tormented Matsushita. "I didn't kill him. But. . ."

Shiro Shibaura, of the personnel department, was deeply happy that Usami died. If he'd gone on living and had sent more of those letters, Shibaura might have killed himself.

He had vowed never to tell anybody about that, not at the cost of his own life. Then, why had he told Usami? It must have been because Usami reminded him of a priest. A priest is forbidden to tell what he hears in a confessional. At the time, he felt as if he were confessing to a priest.

"Please—listen. . ." he had sobbed. Then he virtually clung to Usami, telling him about the hit-and-run killing.

He hadn't been to blame, that much was clear. He was on his way home from a bar. Near an apartment building, a fat man suddenly jumped in front of him. It happened quickly. Though he'd had only one beer, he had been drinking. Almost without thinking, he started the engine again. He did not look back.

The following morning, he looked at the paper. He remembered reading the item timidly. To his surprise, the victim had been a managing director of the S Commercial Company, one of Sanei's important customers. Not only that, he'd been coming to the apartment building where his secret girlfriend lived. For a time rumors ran rampant. But the scandal about the director grew to such proportions that almost everybody lost interest in it as an incident of hit-and-run.

If he'd kept the matter to himself, it would have ended there. The other guy was clearly wrong. Shibaura had little feeling of guilt except for having driven away from the scene. He had been the only one who knew about it. Why, then, did he feel like confessing to Usami? Psychologically, he felt confession would bring absolution. That was it. Usami had only said, "Yes," and "I see," like a priest. Shibaura had been grateful to Usami.

The confidential letter dated the eighth shocked him, frightened him, and made him want to kill Usami. He had died. Someone had killed him. But wild horses could never drag the story out of Shibaura.

The typist, Yumiko Murase, may have handled the matter in a cooler way than anybody else. She read the letter, dated the eighth, at seven on the evening of the ninth. Because she lived in a small satellite town of the city F, it took a day for the letter to reach her. It arrived in the morning while she was at work. She read it that evening:

"A need for money has come up. Please transfer one hundred thousand yen to general account 821-5613 at the S bank, no later than December eleventh."

It was signed Taro Usami. There were two days left before the deadline for the transfer.

On the morning of the eleventh, Yumiko phoned the office saying she'd be late. At nine ten, she pushed open the door of the local branch where she did her banking. The Sanei company made transfers of salaries and bonuses to its employees' banks. Yumiko's end-of-year bonus should have been transferred to her account December 7.

Filling out a form with her own account number and indicating she wanted one hundred thousand yen transferred to general account 821-5613 of the S bank, Yumiko hurried to the counter. As she left the bank, she saw a man on the opposite side of the street. It was Akira Atsuta, chief of the business department. He was hurrying and looked pale. No need to be a detective to figure it out. He must have received one of those elegant blackmailing letters from Usami, too, and probably was on his way to do whatever he'd been asked to do.

Yumiko thought, "I wonder what Atsuta told Usami?" In her own case, it had been the kind of man-woman relationship that happens in all companies between high-ranking men and lower-ranking women.

A year before, Yumiko had fallen in love with Mr. S of the technical staff. He was married and had children. From the beginning, it was clear he had no intention of marrying Yumiko. But, he was exciting, attractive—the type Yumiko admired. She was already an old maid at thirty-three and not so pretty, either. The words S used to entice her were of the driest. Late one night, when they were in a bar, both having drunk too much, S said, "Looks like I'll have to spend the night away from home. What d'you say? Lending it to me won't wear it out."

His rude words thrilled her, and they immediately went to a hotel. They had sex until they were tired of each other's bodies. Then, Yumiko discovered herself pregnant. Handing her two hundred thousand yen for an abortion, S said, "Pretty high rent. This ends everything between us."

Then the humiliation, the suspicious hospital, and the position she had been forced to assume on the surgical table. Then a man—even though a doctor—she'd never seen before did what he liked with the part of her body he should never have touched. The scalpel, which she feared, invaded her body. While understanding she was paying for something she had done, she suffered a festering wound.

Even an old maid left on the shelf has her pride. It was to cleanse herself of the resentment she felt for S that Yumiko confessed the ugly truth to Usami. Then she received that nonchalant letter. She had no choice but to comply with his demand.

For those who received the official-looking blackmail letters, Usami's death was a shock. Nor were Yokomizo, Misumi, Matsushita, and Shibaura the only recipients. There were also Atsuta, Nakanishi, Murayama, Nakajima. . . .

All had two things in common. First, they suspected someone had murdered Usami and suffered both anger and fear at the sight of Usami's odd right-slanting script, in which the letters were written. Second, they had made up their minds to remain eternally silent about what they had confessed to him and about the way they had complied with the demands in the letters. If any one of them were pushed to extremes and mentioned either of these things, he would become a murder suspect.

4

Six months after the incident, headquarters for the Taro Usami murder case was closed. It had been a cold winter. Now it was late May, with the greenery of trees inviting the eye to rest. As the investigation dragged out, the notion that the death was suicide gained more acceptance. This further retarded the search for a solution, since it lowered morale and robbed men of the enthusiasm essential to a successful investigation. Sarcastic investigators said it bogged down because of rotten luck: the murder took place on Friday the 13th; there were thirteen suspects.

Before the final closing of investigation headquarters, there was a meeting of Takahashi, Kono, and Kimura. Kimura was eager to close headquarters. There was much work in the department, many cases, and tying up too many men on a job that showed no signs of coming to a conclusion seemed a waste. "Calling it murder must've been a miscalculation," he said with regret. Takahashi and Kono were silent, neither agreeing nor disagreeing. But Takahashi looked wretched.

Kono said, "I've no objections to closing headquarters. I don't think new facts will turn up. Still—I don't think we should give up, either. Let's simply reduce the scale of the operation. Put me in charge."

"You mean, you still don't want to give it up?" Kimura asked.

"Yeah. That's right."

"Stubborn?"

"Nope. I'm adopting a waiting policy. Let the other guy tip his hand. I think that's the way—"

"Waiting policy?"

"Yeah. Let me have Shibata and Kawanishi."

"O.K.," Kimura said. "You've got it."

Yumiko Murase, the typist with Sanei, gave notice six months after the murder. She said her mother had died and there was no one at home to look after her father, who had grown old.

It was a fact; her mother had died. Further, the only person home with her father was a third son, who was a second-year student in high school. Under these circumstances, it was hard to block her request. But she was an excellent typist, and they would have liked her to remain. Yumiko persisted, and the company accepted her resignation.

But she had said to a fellow worker, "I don't like the gloomy feeling around here. The murder isn't solved, and everybody suspects everybody else. I can't stand working in such an atmosphere." Maybe this was her true reason.

The day of her resignation, with nothing but a suitcase, she left her apartment. She had given her stereo and TV to one of the girls in the office. She flagged a taxi, and told the driver to take her to the airport. When people from the office who had come to see her off heard this, they must have thought it strange. Yumiko's home town was a small village in the mountains, three hours by train and another two by bus.

An hour later, she was on a plane. As she watched the city of F receding through the small, round window, she thought without regret, "Well, goodbye to that—"

Yumiko's home town was so small she could not tolerate it even for a day. The city of F was only a provincial town, too, where rumors were always plentiful. The plane was headed for Tokyo. A vast city of twelve million. A cold city where a corpse might not be noticed for a year by neighbors in the next apartment. A good city to hide in. "Crime." A cool smile played over Yumiko's face. She smiled with pride at the thought of the perfect crime she had committed. She touched the case in her lap, the reward. There were a lot of zeros after the first figures in the four bank books in that case. They represented the triumph of the mind.

She had come upon the notion for the crime about a year ago, at the time when there was talk of her marrying. She had begun thinking like a murder novel. Usami knew about Sand her abortion. Suppose he should demand money for keeping her secret? Yumiko knew she would probably make the utmost efforts to get that money.

When the marriage fell through, Yumiko expanded the idea. "Now—look at this. . . ." Usami was a money tree. He was just full of private secrets. For one like Usami, who would never get ahead-maybe even precisely because he wouldn't—it would be wonderful to turn all these confessions into money. Next, Yumiko thought, "If he won't do it, why don't I turn them into money myself?"

For a year she made preparations. The most difficult thing was copying Usami's strange right-slanted handwriting. It took a year to do that. The next thing was knowing how much to ask each person for. Finally, she decided to ask for more in the upper echelons of the company. This seemed in keeping with principles of social justice and with ideas of the chivalrous bandit. She would keep the text as simple as possible—and be suggestive. . . .

"A need for money has come up. Please transfer ___yen to general account 821-5613 at the S bank no later than December eleventh." She signed Taro Usami. Taking up her pen, in the letter to Kenzo Yokomizo, she wrote "five million yen." Stopping, she asked herself if this might be too much. Then, with a toss of her head, tightening her abdomen, she said, "Nope. It's a gamble. With gambling, courage is necessary."

Although she knew little about business, lately she had noticed something suspicious about Yokomizo. She did not know what it was, but she felt certain he was up to something. If it were a business secret, he would be willing to pay that much.

Finally, intelligently, she wrote a blackmail letter to herself as a coverup. She wrote in figures for one hundred thousand yen.

Total: thirty-two million one hundred and seventy thousand yen.

On the twelfth of December, she went to the bank to check the account in the name of Taro Usami. All thirteen people—including herself—had paid in the amount she counted on. With the automatic disbursement machine, it was a simple matter to draw the money out.

"A pity about Taro Usami," Yumiko thought. But to make her crime perfect, he must die. When the end-of-year party was a little noisy, taking care to leave no fingerprints, Yumiko set a highball containing potassium cyanide on the table before Usami.

But as the plane swung over Tokyo International Airport, Yumiko murmured, "Stop thinking about the past. The future is ahead of you."

* * *

Inspector Kono was listening to a report by Detective Shibata in an official phone call from Tokyo. Shibata's voice was clearly excited.

"Yumiko Murase's activities since arriving in Tokyo. At a real estate office, she sublet an apartment—two rooms and a dining-kitchen. The building's in Shinjuku Ward, fifteen minutes from the Kabuki-cho entertainment district. She paid deposits and a year's rent, totaling five hundred thousand yen. Next, she negotiated to purchase the management rights and equipment of a nearby coffee shop. Total expenditure was fifteen million yen.

"When she left Sanei, because of outstanding debts, her retirement fund came to only three million yen. Looks as if you're absolutely right. Yumiko Murase is the murderer. The waiting policy has paid off. Still, somehow I feel extra sorry for Taro Usami. I guess he just knew too much about too many people."

"That's real nice," Kono said.