Читать книгу Dance and Costumes - Elna Matamoros - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4. THE ‘BALLERINA’, MUSE AND STAR. THE EARLY TUTUS

ОглавлениеIf there is a famous image in the history of dance, it is the painting by François-Gabriel G. Lépaulle picturing the opening scene of the ballet La Sylphide, today at the Musée de les Arts Décoratifs in Paris; the great success of this ballet and its after-impact were echoed in the numerous engraved copies and reproductions of Lépaulle’s painting made throughout the years.1 In this image, the dancer Marie Taglioni –characterised as the Sylph–is kneeling next to the armchair where James (the male protagonist of the ballet) sleeps. The dancer portrayed as the Scottish character –as in the title of the original painting and in most of the engravings– is Marie’s brother, Paul Taglioni, but sometimes the dancer is also identified as Joseph Mazilier [or Mazillier] (1801-1868).2 He was a French dancer, teacher and choreographer famous for having created ballets such as Paquita3 or Le Corsaire,4 as well as for having starred in La Sylphide next to Marie Taglioni on the evening of its Paris Opera premiere, in 1832.5 Although Paul Taglioni developed a prestigious career in some opera houses in Europe, he evidently did not reach the popularity nor the stardom that his sister achieved; and although he often danced the role of James with her, his interpretation was never considered at the level of Marie’s. The same thing would happen with most of the future partenaires of the ballerina.6 Going back to Lépaulle’s painting, not only does the name of the dancer vary from one reproduction to another, but even sometimes, simply, the name of the young man who rests next to the beautiful Taglioni does not even appear. The identity of the dancer portrayed is a doubt that has already become an anecdote.

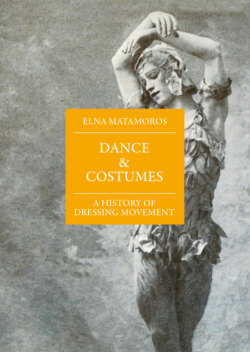

4.1 - Marie Taglioni et son frére Paul dans le ballet de la Sylphide. Oil on canvas by François-Gabriel Lepaulle, 1834.

It is an example of the little importance that the male dancer had on stage during the Romanticism, although we must also consider that Marie Taglioni’s triumph the evening of March 12, 1832 was such that all the others’ performances were blurred on stage. We have not even found an image, for example, of the dancer who gave the carnal replica to the Sylph in this story, the dancer Lise Noblet (1801-1852), in costume as the beautiful Effie: “the earthly rival of the winged shade”, in Levinson’s words,7 with whom James was engaged and whom he abandoned in the moments before the wedding ceremony, obsessed with the image of the beautiful, intangible and capricious Sylph.

The female hegemony in the world of dance was clear; another illustration, as a graphic example, shows the first scene of La Sylphide with Marie Taglioni performing a beautiful arabesque partially covered by the armchair of James, who is just barely sketched in the image. Obviously, it is no coincidence: Taglioni, portrayed in detail, keeps the attention of the viewer, who barely stops to look at the dancer who rests in the foreground at the lower part of the image.8 It even seems that the artist has used two different pictorial techniques in the same work: one with coloured ink for her, and another with light charcoal for him.

This was the real situation of the dance world around 1830, when the great male dancers had practically retired and the audience began to be dazzled with the unreal, fragile and sometimes sensual figures that filled the new ballets.9 There is no doubt that since La Camargo astonished the audience with her ‘virile’ techniques of jumps and acrobatics, the figure of the male dancer had been left, gradually, in the background. Even the great Ballet Masters –all men, of course– were aware of the challenge before their very eyes. As an anecdote –or an indication– the famous Carlo Blasis changed the illustrations in the two successive versions of his excellent treatise on dance: in the first book –his Traité élémentaire, théorique et pratique… of 1820– there were only seven female figures for fifty-seven male ones, which also showed, in all the plates except for one, the bare torso and arms.10 In its second version of the book –notably enlarged and written in English: The Code of Terpsichore, of 1828– the proportion of male and female explanatory figures was not only balanced, but there were even more women than men –fifty-one vs. forty-five, respectively–, and almost all of them, were wearing sophisticated dance costumes.11