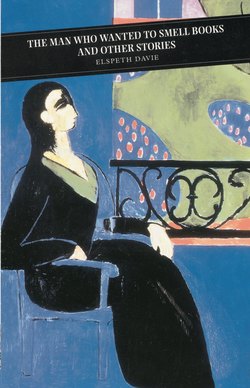

Читать книгу The Man Who Wanted To Smell Books - Elspeth Davie - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Spark

Оглавление‘I FIND IT strange, Mr Abson, that your face doesn’t change much at the things I’ve been telling you. But you do listen, don’t you?’

‘I listen, Mrs Imrie. I find what you say very interesting.’

‘“Interesting”! But you do feel what I’m saying to you? About the little puffs of smoke between the tiles … the dog howling at the back?’

Abson was thoughtful for a few minutes, his round, black eyebrows raised, melancholy eyes fixed on the floor.

‘Later, Mrs Imrie. Things come over me later. When I’ve had time.’

‘When you’ve had time? But you have lots of time, Mr Abson. Who’s disturbing us? You’re a person of feeling, aren’t you? A person would need to be inhuman not to respond to what I’ve just told you.’

‘That’s how I’m made, Mrs Imrie.’

‘How? Not inhuman, I hope?’

‘I mean I go over things later.’

‘Later? How late?’

‘Indeed I am not!’ exclaimed a girl who had just opened the door. ‘It’s all your crazy clocks running on again!’

‘I’m not referring to you, Brenda,’ said her mother. ‘I’m talking to Mr Abson here who feels everything later than other people.’

The girl shrugged herself through the room and over to a corner where she hung up her coat and stared close and long at a small mirror. As she watched her daughter combing out her hair the woman at the table seemed at ease, as though her own nerves were being combed out strand by strand from the knotted frizzle they had got into while sitting too long with the passive Mr Abson. But after a while she turned to him again, speaking, however, in a more patient and relaxed tone.

‘How late do you mean, Mr Abson?’

The man gave his peculiar half-sigh. That is to say, he drew in his breath, held it for a while, and expelled it almost without a sound. But, halved like this, it was also irritating, as though he had no wish to give generously of his feelings – even feelings of desperation – like other people.

‘How late, then?’ Mrs Imrie repeated.

‘At night. When I go to my own room. In bed probably. I go over things when I’m in bed. I suppose that’s what I usually do.’

It was quieter in the room. The girl had stopped combing her hair, or she was combing it very lightly. The woman took up some sewing again. ‘You mean things don’t strike you right off? Even funny things you see or hear?’ Mr Abson turned his eyes towards the window, but said nothing.

‘I suppose that means you don’t sleep well.’

‘Not always.’

‘I’m glad I’m not troubled like that. With me it’s when my head touches the pillow. Or when would I ever get my work done next day? I’ve no time to think day or night, it seems!’ She sewed steadily for a bit, and once she whispered: ‘The whole roof caving in ..!’

After a while Mr Abson gathered up some papers from the table into a brief-case and prepared to go into the other room which was officially his for the evenings if the family were not entertaining visitors in there. They had only a very hazy idea of his job for he had not talked much about this. But they knew his firm made tiles and pots and mugs, and they associated him with a peculiar foreign jar they had once seen there – long, black and white, narrowing at the top to show that nothing was to be got out of it and nothing put in except perhaps a bare twig or two. And yet with a mournful, drooping lip to it.

‘Don’t go unless you must,’ said Mrs Imrie. ‘It’ll probably take a bit to heat up in there. Jim and May will be back soon and we’ll have a cup then.’

‘I’ll come back later then, if I may,’ said Abson. He went out and they heard the door of the other room close behind him.

‘Always later!’ exclaimed Mrs Imrie. ‘I’m afraid later’s not much use to me. I’ve got to have the laughs on the dot, and the crying too. And I like a gasp when it’s tragedy – even a blink would be enough. Something. When I told the butcher about them throwing the twin babies out of the window and the fireman nearly gone himself with the smoke, he doubled over as though he’d a pain here – doubled over his knife. Mrs Liddel did more. She wailed out loud.’

‘There was a safety-net, wasn’t there?’

‘Has the world gone quite heartless? Yes, there was a safety-net. And lots of people down below, including that mother – watching her two babies being thrown, one after the other, out of a fourth-storey window!’

‘Anyway, they’re safe. No damage done.’

‘Talk about sleeping! Imagine that poor woman’s dreams when she does close her eyes. Will she ever get it out of her head? No she will not. Some people have reason to lie awake at night.’

‘We don’t know what’s in Mr Abson’s head.’

‘No, we don’t. Whatever it is, it doesn’t show on the face. The strangest thing about buildings when they collapse is the slowness. It’s like a slow-motion picture. A sag here and a bulging there, and a slow, slow puff of dust.’

‘I’ve seen something like it on TV.’

‘The sparks are dangerous. I believe they can travel miles.’

‘And still keep alive?’

‘Seemingly. In a wind.’

‘Surely not miles?’

‘A long distance. You think they’re dead, and the next thing you know there’s a fire blazing away miles from the first place.’

‘A single spark,’ said the girl.

‘But if it’s alive, after all – and travelling fast.’

‘A dark spark,’ said the girl again, brooding on it.

‘And more dangerous for not shining,’ said her mother. They sat in silence for a few minutes till the girl took up her comb again and began on her hair. This time there was a faint cracking and she laughed. ‘More sparks,’ she said, drawing out a strand and letting it float free from her head.

‘Look, leave your hair alone,’ said her mother, ‘and get that comb away from the table.’

Later on, twenty minutes or so before her brother was due back, the girl knocked on the door opposite and opened it. Mr Abson was sitting there with his papers at a small table. The room had not heated up and as she spoke she could see the little white puffs of breath before her in the air.

‘You haven’t put on the light yet. Shall I come in?’

‘Yes, come in,’ said Abson. ‘Have your brother and his fiancée arrived?’

‘Not yet. “Fiancée” is idiotic. Why do you keep using that word?’

‘I took it for granted.’

‘Well don’t. You haven’t been here long or you’d know the number of girls he’s brought home already. We keep off the word.’

‘What is the play they’re rehearsing?’

‘I’m not very interested to talk about them. I don’t know what it is. All I know is he’s a sailor and she’s a school-mistress. Have you noticed how nearly all the women in these plays turn out to be teachers? Last year he was a painter and she taught Algebra. In the end they show they can take off their glasses and everything else the same as other women. But of course only for sailors, painters or murderers. Is that fair? Never for anyone else – never a male teacher, for instance.’

‘Is your brother a good actor, then?’

‘I’m not interested in that. But there’s one thing. I’ve been behind the scenes when they’re taking the paint off.’

‘Yes?’

‘It’s strange, frightening maybe. They take a blob of grease and wipe off a pair of round, black eyebrows, or a frown or a luscious pair of lips. They can clear patches of white fright from their cheeks in one stroke – grease off a blush as quickly as you’d wipe round a dinner-plate, and underneath, when they’ve wiped off every mark, their faces are dull … dull!’

‘It’s not that. But undramatic perhaps. Unexaggerated.’

‘No. Dull. When you take off eyebrows, for instance, the surprise goes out of the face. Yours is the opposite.’

‘Mine. My what?’

‘Your face, Mr Abson. When you wipe it off, yours must be exciting.’

There was silence in the room. The man turned his eyes slowly, still keeping his head stiff.

‘When I say “wipe off” I’m not referring to paint, with you, of course.’

‘No? What, then, could I wipe off?’

‘I’ve no idea what it could be.’

‘I take it you find the surface dull –no dramatic eyes or lips?’

‘But underneath – exciting.’

‘Where exactly does it break through?’

‘It doesn’t. But I can infer it, from what you say. At night, for instance, in your own room.’

‘Miss Imrie, if you’re trying to make up for anything your mother said – don’t bother. She’s been good to me. She likes me well enough even if I do get on her nerves. And I’m not to be here long. Why bother yourself?’

‘Miss Imrie! Part of your trouble’s politeness. Like fiancée. Politeness dulls the face. It’s nothing to do with my mother, though naturally she likes excitement. She imagined that being abroad so long you’d have lots to talk about. But it hasn’t worked like that and she doesn’t hold it against you. It’s a dull street, that’s all. A dull street, a dull town, a dull country. We’re pretty dull here compared with lots of them, aren’t we?’

‘And she has a feeling for drama like your brother?’

‘She likes the applause and the gasps when she has something good to tell.’

‘Something good?’

‘Ah, you know what I mean. Don’t fold up. Don’t start moralising. I mean good and bad at the same time. Everyone likes sparks and fire-bells. Why else would they come running?’

‘And the screams?’

‘There were no screams. And no one was hurt.’

‘There would be bigger crowds for screams, I can tell you that.’

The girl sat still and watched him. After a while she sighed, took the comb from the pocket of her jacket and drew it smoothly down one side of her head from the middle parting, bending her head right over so that the hair swung out away from her neck and ear. Her upturned eyes showed a rim of white round the lower lid and gave her a look of fixed surprise.

‘It’s not quite dark enough yet,’ she said, ‘and maybe not the right sort of day – but often, when I do this, I can get not just crackling, but actual sparks as well. Frost and darkness are the best. I know,’ she smiled, ‘that it can’t happen often with men. There’s got to be plenty of hair for it – something you haven’t got. But more spectacular still …’ she paused and smiled again into the dim room, ‘is the last thing I take off at night. It’s not just sparks but flashes. The quicker it’s done, the brighter. If I rip off the vest and toss it away I can get great, blue flashes that sting my arms and back. And if the room is absolutely black it’s like lightning – crackling, stinging lightning. But the stuff’s got to be silky, nylon and that sort of thing. Nothing dull or thick. Not everyone believes this. People can get very stuffy about electricity too, you know, as though it ought to be confined solely to lamp-bulbs.’

‘There’s your brother now,’ said the man, unstiffening to the sound of the key in the front door.

‘Is it? There’s another thing. Some people think you’re getting sexy if you say “sparks in the hair”. “Electricity” is as good as an invitation, and if it’s electricity and underwear they’re waiting to be eaten up.’

‘Yes, it is them,’ said the man. ‘I can hear the girl too.’

‘… Waiting to be eaten alive or ready to pounce themselves. It comes to the same thing,’ said the girl. ‘No, that’s my mother’s cousin. She’s got a key and comes in on Tuesday nights if there’s anything she wants to watch. No, it’s early for them yet. The sad thing about those ones – whether they’re waiting or pouncing – is they’re still dull, terribly dull and sad.’

‘You’ve little idea at your age how tired people can become,’ said the man.

‘At my age! Some of my friends are as tired right now as they’ll ever be. Tireder, for instance, than my mother ever was or ever will be. Tired wasn’t what I was talking about. It was dullness. A mean, suspicious, greedy, beady-eyed dullness, if you can imagine that!’

The man gave a laugh. He put his hands to his face and rubbed it hard for a moment, first his forehead, then his cheeks. He was breathing quickly.

‘What’s that for? Are you cold?’

‘Maybe. I’m trying to wake up, warm up. Anything to scrub off those words.’

‘Those words were meant to go over your head. They’re nothing to do with you. Not one of them landed on you – so you can stop scrubbing.’

Abson’s hands were suddenly still, his fists clenched at the sides of his head. He turned on her angrily exclaiming: ‘And you! Look – you can stop nagging! Stop lecturing me!’

‘That’s better,’ said the girl, leaning her elbow on the table so that now the other wing of hair hung down to touch his papers. ‘I don’t mean to nag. I think a lot of you, and a lot about you. And do you know how I think of you? I think of you as a sort of dark spark.’

There was a tremendous crash from the outer door on the word ‘spark’ and a sound of voices filled the hall. The wall behind them rattled with the buttons of overcoats being flung at the pegs on the other side, and there was a thumping on the wainscoting where heavy shoes were kicked off.

‘That can’t be just the two of them,’ said the girl, straightening up and folding her hair back behind her ears. ‘Maybe they’ve brought the whole group back. There’s five there at least. Do you hear five?’

‘But have they got to have the wind through the whole scene?’ a voice was calling out plaintively in the hall. ‘And has it got to be a gale? Two pages! Tenderly! Have you ever tried speaking tenderly with a howling gale at your ear?’

‘A dark what?’ said Abson.

‘It’s the last scene,’ said the girl. ‘They’re talking about the bit where the two of them – I told you about the sailor and this woman – they’re waiting for news of his son in the storm. There’s a bridge been blown down or something.’

‘A dark what did you say I was?’ said the man.

‘Just a minute,’ said the girl. ‘Listen! How many actually are there? I’m not going out there till I know. If it’s five then it means Ben’s around. I’m not going out there if that Ben has attached himself again. Well, it can’t be helped. I’ll never know if I don’t look, will I? Are you coming out?’

‘Not yet,’ said Abson.

‘Later then,’ said the girl. When she opened the door a brilliant shaft of light and noise cut through the dark room. The man inside had a glimpse of a boy sitting on the bottom stair taking his boots off and a young woman leaning against the wall unknotting a headscarf. The girl’s sudden appearance in the hall caused a moment’s silence then a burst of acclaim from at least five voices. She passed through them, leading the way into the other room and they went after, dropping the boots and waterproofs, shaking the rain from their hair. They followed her and the door closed beyond. Suddenly the hall was silent. It was quite silent and empty.

A long time later the group in the sitting-room heard steps going upstairs – or rather the boy who had sat taking his boots off on the stairs heard them. He was now leaning with his elbow on the hearthrug eating toast and he held up his knife with the butter on it for silence.

‘Who is it?’ he asked.

‘I’ll get him,’ said Mrs Imrie, and she went out to find him already round the corner of the stairs. ‘Why, you can’t go up yet. It’s early. Aren’t you taking a cup with us before you disappear?’

‘For a few minutes – with pleasure,’ said Abson, coming down slowly.

Like her daughter, Mrs Imrie felt that politeness at this moment was a mistake. Why ‘pleasure’ with his face? With his reluctant steps? She had once had someone who, called down like this, had stuck his head in the door, made hideous faces at a group of old ladies and withdrawn. And been loved for it.

‘Creaks on the stairs,’ remarked the boy at the fireplace, watching Mr Abson who was now sitting with a cup of tea in his hand. ‘That reminds me.’

‘Go on!’ voices encouraged him. ‘Give us the story!’

‘No, it’s not a story. There’s nothing to it.’

‘Go on!’ they shouted.

‘Not a story – not an experience even. A sensation. A stirring of the hairs of the head. It was this perfectly ordinary suburban villa belonging to a schoolfriend’s family – an ordinary red and yellow brick affair.’

‘All right. Don’t worry,’ said someone. ‘It was ordinary. We got that.’

‘I was staying the weekend. I had my dog with me. Well, each evening at the same time – eight o’clock – footsteps going upstairs. The first time I said “Who is it?” – nobody’d heard them. And the second night: “Who is it?” Nobody heard them. The third night – same thing. No one had ever heard them except me.’

‘The dog?’ murmured someone who’d heard the story.

‘I’m coming to that. Each time it happened the dog would get up and whine at the door of this room until I let him out. We’d both stand at the foot of the stairs waiting for the last creaks going up at the top. Then the dog would give one yelp, turn his back to the stairs and sit huddled up to me without moving a muscle. It happened three times. In the end the family, including the schoolfriend, had taken an intense dislike to both of us. Can you blame them? Each time they came out of their cosy, plush drawing-room they saw me gaping up the stairs and the dog hunched round the other way. They could hardly wait to get rid of us. In the end I had to carry my own suitcase to the station in the pouring rain. I can still see myself trudging past their long, cream car at the front gate. The schoolfriend hardly spoke to me again – avoided me as though I had the plague. Well – there you are. A gloomy silence in the audience. Didn’t I tell you you’d be disappointed?’

‘No, not a bit,’ said a girl from the other side of the room.

‘The fact that it lacks all drama makes it more real. Now I know it happened.’

‘Thanks.’

‘Even in spite of, or because of the dog. Because prowling, howling dogs are common in ghost stories. But yours just sits there on the mat. He’s a pet. He’s sweet. I know him.’

‘Thanks again. His name is Brown. I suspected it was a boring little tale.’

‘Surely not just Brown?’

‘Simply and literally Brown. Nothing more nor less.’

‘Well anyway, I liked the way you made nothing of your sensations. I think that’s drama, or is it anti-drama? Nothing more about your hair rising. Or your sweaty palms.’

‘I don’t know what it is, but whatever it is, it hasn’t got over the footlights.’

‘I adore ghost stories!’ exclaimed Mrs Imrie.

‘Mr Abson,’ the boy said, ‘did you ever do any acting when you were young?’ He was leaning against the fireside wall with his knees drawn up and he now gave his full attention to the older man. This attention was compelling as though silently, deliberately, almost while they were unaware, he had smoothly pivoted the focus of the whole room round in one direction. By the steadiness of his eyes, the absolute stillness of his thin hands – clasped together and just touching his lips as though he were preparing for an absorbing story – he silenced the rest of the group. They might have been under iron command not to move. Nobody moved or spoke.

‘No, I never did,’ replied Abson. Mrs Imrie gave a faint, a very faint, exasperated sigh.

‘Well no, I suppose that’s not absolutely correct,’ said Abson, nervously smiling. ‘I was, as a boy, I remember, once given the part of a tree in some play or other.’

‘Yes?’ came the boy’s voice, quick and serious. There was unusual power in this young man. By split-second timing, by the sheer force of his expression and tone of voice, he had prevented a burst of laughter from the rest of the room.

‘Well, I suppose you wouldn’t really call it a play – it was probably a kind of ballet,’ said Mr Abson, still smiling, though there were no answering smiles from the others. ‘It didn’t, you’ll agree, need great dramatic gifts.’

‘On the contrary,’ said the young man at once.

‘I beg your pardon?’ Abson looked surprised.

‘On the contrary it would need rather special dramatic gifts to express this.’

‘Well, hardly human ones.’

‘Superhuman, then. Did you enjoy it?’

‘I think I did, now that you remind me. I’d really absolutely forgotten the experience.’

‘Perhaps there were others.’

‘Others?’

‘Perhaps there were other parts?’

‘I don’t think so – unless you count noises off. Anything I was asked to do was strictly non-human or background.’

‘To do a tree you’ve got to be more human, not less. You’ve got to be so human you can reach people and even go beyond them. That way you might just hope to arrive at your trees and rocks. Isn’t that so?’

‘Yes, that’s an interesting point,’ said Mr Abson.

‘What kind of tree was it?’ asked the young man.

‘An apple tree,’ said Abson. There were still no smiles.

‘In blossom or with apples?’ asked the young man.

‘Just leaves,’ said Mr Abson, remembering so much now that his face was warm for once. His eyes stared from a nucleus of shadowy, scalloped green. ‘And an interesting thing I remember – it was not to be a tree in the wind. That was definitely ruled out. Yet you’d have thought they’d have insisted on wind to make absolutely sure people knew what they were looking at.’

‘No, too obvious. All that thrashing and swooshing about, as though all trees must be in perpetual gales to show they really are trees. What rot!’

‘Well, maybe you’re right. Anyway, I had to make only the smallest movements – a kind of microscopic growing.’

‘Oh God – that’s difficult enough!’

‘Not much more than a vibration – I’m not sure about this.’

‘Your producer was a master then?’

‘He was quite a talented young man, I think,’ said Abson mildly. ‘A vibration, or was it perhaps the dry bark cracking a bit in the sun?’

‘God knows!’ exclaimed the young man, at last permitting himself to smile. At once the rest of the group released themselves from his control. The red-haired girl put her head back on to the knee of the man behind who after simply lifting up strands of the long hair and letting them drop, began plunging his fingers up from the roots, tugging so roughly through the knots that the girl had her eyes screwed up each time his hand came down. It looked like torture but when her eyes were open the expression was blissful. Mrs Imrie put the cup she had been holding all this time down on to its saucer. Neither the ghost nor the tree had exactly electrified the atmosphere for her. She decided that at a suitable moment she would give them the roof crashing in the night with the sparks flying off, and the butcher bent double over his bloody trembling knife.

‘Well, I suppose I should be getting up now,’ said Mr Abson. ‘I’ve very much enjoyed … but I think I’d better …’

‘With your early start in the morning …’ Mrs Imrie agreed, rising briskly to accompany him to the hall. But the boy who sat at the fire was before her. It was now almost an acrobatic feat to cross the room over the outstretched legs but he was up and out at the same moment as Mr Abson started to go slowly up, one hand on the banister. Through the open door they saw the young man go round to the side of the staircase and walk down the passage, sliding his own hand up the banister as far as it would go. For the last few inches he had to stand on his toes reaching out, his long fingers stretched hard against the wood, his body, straight and tense from head to foot, leaning forward at an angle along the banister. This sight gave the one or two who were watching a strange frisson of dread or elation. They watched a contact missed by inches, an effort to reach still further, doomed. Mr Abson’s hand moved smoothly on up the banister. He disappeared round the bend of the stairs without looking back. For a few moments longer the boy remained stretched out. Then his arm dropped like a weight. Mrs Imrie’s daughter joined him in the hall.

‘Poor ghost,’ said the young man, turning slowly from the stairs. ‘One of you should take a look at him now and then. Just once in a while – look at him, will you?’

‘I do. Honestly I do. Before you all arrived we were having a long talk.’

‘Or he’ll fade out. He’ll absolutely fade out.’

‘Don’t you think we look after him well?’

‘Look after – yes. Look at him!’

‘Why should he fade out? I see him as a sort of dark spark. He can be brought to life all right. But it takes constant fanning. Bellows even.’

‘Use them then!’ He went quickly past her into the room where Mrs Imrie had already started the conflagration. Chimneys were crashing in the street, red, green and orange flames unravelled from window to window, and from one a white bundle dropped, then another, to the gasping crowd below. Great swirls of living sparks were being blown for miles along the rooftops. No gush of water could quench these. No hosepipe, however long, catch up with them.

Mr Abson stayed with the Imries for two months more and then his work, whatever it was, took him to a neighbouring town where he remained another three months. And there he died. Three months ago. They had almost forgotten him. Or at any rate his face was not absolutely clear any more. But the manner of his death which they found in a newspaper, hearing further details from an acquaintance who lived in that town, jolted their memory in a peculiar way. He had failed to get out of the way of a lorry, the paper said. He had stepped out, said a witness, and stood still.

‘No, it was not deliberate, if that’s what you mean,’ said Mrs Imrie to a friend who had come in. ‘If it says “failed to get out of the way” then that’s exactly what it means. I wouldn’t say, now I come to think of it, that I ever saw him do anything exactly deliberately, would you, Brenda?’

‘Never. It would be that he didn’t know whether to put his feet backwards or forwards. I’ve seen him do just that on the thresholds of doors.’

‘You will never really know, will you?’ said the friend.

‘Never know what?’

‘Nothing. It’s all right.’

‘It’s terrible,’ said Mrs Imrie. ‘Poor man, he should have shown more in his face. That would have helped him. It would have helped people to take notice of him too.’

‘He would be clear enough to the lorry-driver,’ said her son. ‘It’s going to add another ghastly hazard to life if you’re only visible to motorists if you’ve got an interesting expression.’

‘He only thought of things later when he was in his own room. That wasn’t good for him, was it? Like secret drinking or something. I should have interrupted him oftener.’

‘Why are we talking like this? Could we help that bloody great lorry bearing down on him?’

‘Oh, how I sometimes wanted to give him a push!’ exclaimed Mrs Imrie. ‘If I could have given him a push when he was standing there – one hard push – it would have saved him!’

‘Rooted. Rooted to the spot,’ said the girl. ‘What does that remind you of? Are you thinking of a tree?’

‘Am I what?’ said her mother.

‘If he’d even learnt to dance, oddly enough,’ said the girl. ‘There are people who learn to dance simply to help them move their feet properly – to balance themselves. Did you know that? Hospitals send them.’

‘Hospitals now!’ cried Mrs Imrie, holding her hand to her head. ‘So now you make out he was a sort of patient. Some kind of case, I suppose.’

‘It never even crossed my mind. I simply remember he sometimes asked about dances I’d been to.’

‘Near enough a case,’ said the friend, ‘if he just stood there.’

‘What are we talking about now?’ said Mrs Imrie. ‘Has it come round to this again? “Failed to get out of the way” – I interpret that simply as I see it set down on the page.’

‘If you can see it simply,’ the friend said.

During the next few days they could have been no more acutely aware of Abson had be been following them around from room to room over the whole house. His death lit him up for them. He flickered with a red, unnatural light which flared or sank as their feelings about him flared or died. He was not silent. His identity demanded constant discussion and examination. Yet what did they know about him? They had scraped their memories. At the end of the week the girl, for the second time, rang the young man who had sat by the fire.

‘You’ll come round and help us out, won’t you?’

‘If I can. Are you still brooding?’

‘Oh, we’re stuck. It’s hateful. We’d almost forgotten him. And now this. We’ve got to start again, and there’s nothing to go on. He didn’t talk about himself and neither did we.’

‘Why not forget him again?’

‘How can I? I’ve got to get him clear first, if he’s to be properly washed out. What was he like?’

‘Look – I met him once only – at your house.’

‘But you had a feeling for him. Say something about him.’

‘It’s you who must say it. Or you’ll be haunted.’

‘Haunted by nothing! All I can think of is a spark and a tree. And don’t ask why. I don’t remember how they came in or when.’

‘Well think of them, then. Think hard!’

Later that evening, still having nothing to go on, she did think of them; for she was standing outside the open door of his room looking in at the place where, according to him, he had gone over and over things. What things? It was bare-looking now – a small room but with a high ceiling speckled in minute and scabby stars. A tree might grow in here. With an effort she could see it – this dry, grey tree with branches twisted at right angles round the corners of the ceiling and roots that had to bend back to fit the wainscoting. A rustling, creaking, cracking thing, dry to its sapless marrow. At first the dark spark settled lightly there like a crumb of dry ash, dead in the dead, bedroom air. Nothing kindled it here. It needed nothing, but took its life from some stupendous unknown fire blazing away miles from here. And gradually a microscopic speck of red began to burn at its centre. No movement fanned it, but still it expanded, fraying at its edges into palpitating spangles of rose-colour. Suddenly it ruptured, falling away into other sparks which went rolling and spinning along the branches, dropping down and falling apart again, multiplying, sprouting buds and shoots, roots, leaves, blossoms and fruits of green and yellow fire. The tree burned in silence. No part of it was reflected on the walls or the star-scabbed ceiling, and not a spark or speck of ash fell to the ground. At last a single white flame burst from the root and ripped up the length of the tree, reducing it in one flash, like the slashing upstroke of a knife, to ash and blackness. Then to nothing. Spark and tree went out.

‘I feel better about him now,’ the girl told her mother and brother that night after supper. ‘I can put him out of my mind.’

‘How’s that?’ her mother asked.

‘When you put everything together, looking back, you can see he was really alive.’

‘Was he?’ said her brother. ‘But now he’s dead.’

‘He wasn’t dead all the time though. Not grey as we thought. If he’d been dead alive as well as dead dead – that would finish me! But I can forget him!’

‘But he’s dead now,’ said her brother. ‘He stepped off a pavement.’

‘I prefer to think of it as going up in flame,’ said the girl. ‘It suits him – the way I’m thinking about him now. The way he was really alive all the time.’

‘Prefer all you like,’ said her brother, ‘but that’s the way it was. He stepped off a pavement.’

‘Don’t remind me of that fire,’ said her mother with a shudder. ‘Don’t ever bring that up again.’