W.E.B. Du Bois

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

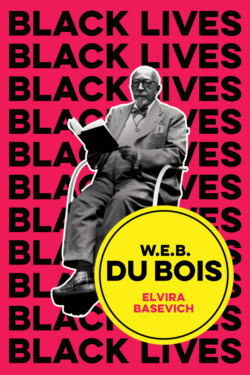

Elvira Basevich. W.E.B. Du Bois

CONTENTS

Guide

Pages

W. E. B. Du Bois. The Lost and the Found

Acknowledgments

Introduction Du Bois Among Us: A Contemporary, A Voice from the Past

Notes

1 Du Bois and the Black Lives Matter Movement: Thinking with Du Bois about Anti-Racist Struggle Today

The black lives lost

Trust: do you see what I see?

Lifting the veil: de-colonizing the white moral imagination

Mourning and moral faith

Notes

2 Student Days, 1885–1895: Between Nashville, Cambridge, and Berlin

Du Bois’s childhood, formative experiences, and student days

Du Bois’s early political thought

The normative basis of anti-racist political critique

The is/ought distinction

A Kantian normative scheme in Du Bois’s political thought

Legal versus civic equality

Ideal versus nonideal theory

A different kind of ideal theory? Du Bois’s ideal of civic enfranchisement and the inclusion/ domination paradigm

Notes

3 The Emergence of a Black Public Intellectual: Du Bois’s Philosophy of Social Science and Race (1894–1910)

The unhesitating sociologist (1894–1911)

Du Bois’s philosophy of social sciences

Du Bois’s philosophy of race: reconsidering racialism

Political and cultural theories of race

Revisiting Hegel’s concept of spirit

Interracial civic fellowship and the cosmopolitan condition

Notes

4 Courting Controversy: Du Bois on Political Rule and Educated “Elites”

Washington–Du Bois debate

The role of the “talented tenth”

The politics of leadership and desegregation in Long Island, New York

Notes

5 A Broken Promise: On Hegel, Second Slavery, and the Ideal of Civic Enfranchisement (1910–1934)

Du Bois in Harlem

Second slavery and democratic theory. A legitimation crisis in the postbellum United States

Du Bois’s philosophy of the modern American state

American Sittlichkeit, or the modern state in concreto

Public reason in the circle of citizenship: on the self-conscious development of institutional rationality

Radical Reconstruction (1865–77): on the self-conscious development of institutional rationality in the postbellum United States

On the family

On emancipated black labor

Why Du Bois is neither an elitist nor an assimilationist

The contemporary implications of a “second slavery”

Mass incarceration and prison labor

On Walmart and Amazon: the two largest employers in the private sector

Building an interracial labor movement

Notes

6 Du Bois on Sex, Gender, and Public Childcare

The Du Bois household

Du Bois and the women’s suffrage movement

Right to motherhood outside the nuclear family

The black church and women as civic leaders behind the color line

Childcare: actualizing the value of the civic equality of black women

Notes

7 Du Bois on Self-Segregation and Self-Respect: A Liberalism Undone? (1934–1951)

Du Bois’s black nationalism and Marxism: economic grounds for voluntary self-segregation

What’s left of the liberal ideal of civic enfranchisement?

Du Bois’s dissatisfaction with the Communist Party

A closer look at double consciousness as an effect of the color line

An orthodox liberal approach: Kant on self-respect

Double consciousness reconsidered: Du Bois’s defense of black self-segregation as black self-respect

Du Bois’s reservation about the desegregation of schools

Contemporary implications: the politics of self-segregation today

Notes

Conclusion. The Passage into Exile: The Return Home Away from Home (1951–1963)

Du Bois’s life, scholarship, and activism in his last decade (1951–1963)

Between domestic justice and cosmopolitanism: the pan-African movement in the black diaspora

After exile: Du Bois’s legacy today

Notes

Index. A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Z

POLITY END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT

Отрывок из книги

Black Lives series

Elvira Basevich, W. E. B. Du Bois

.....

Mutual trust is necessary to sustain the bounds of civic fellowship and a shared sense of political fate. Trust often mediates what one takes to be true and is ready to accept as a feature of a shared reality that binds a stranger’s destiny to one’s own. In granting credibility to an interlocutor, one takes their experiences of the world to be a true representation of the world. Yet in an age of the rapid dissemination of information through the internet and social media, the refusal to trust black voices persists. Distrust and suspicion are the cause of racial violence – a fact exemplified in the killing of Eric Garner. The moments leading up to Garner’s death were caught on cellphone video and watched by millions. A Staten Island resident, Garner was killed in 2014 in an illegal chokehold by ex-officer Daniel Pantaleo.11 Yet there remains little consensus about what the footage means. Prior to his death, Garner repeated eleven times “I can’t breathe,” a phrase that is now a rally cry of the BLM movement. Pantaleo did not believe Garner that he really couldn’t breathe; or else, he simply didn’t care. Likewise, many members of the public still do not believe that Garner’s death was avoidable, or else they simply don’t care one way or another. In effect, they just don’t trust that he really couldn’t breathe.

In an interview, Garner’s youngest daughter, Emerald Garner, responded to the news that four years after Pantaleo had killed her father he was finally fired: “We’re grateful that someone sees what we see.”12 In contrast, the NYC police union leader, Patrick Lynch, denounced Pantaleo’s firing. Lynch asserted that the firing encourages assaults on police officers. Of course, police officers’ distorted perception of their own vulnerability to attack by African Americans rationalizes their use of deadly force in the first place. Moreover, officers often fabricate police reports to suggest a victim posed a threat, knowing that they enjoy the public’s trust that their black and brown victims lack. The public’s inclination to trust police officers and distrust their victims persists, in spite of video footage of fatal police encounters. In response to Lynch, Emerald Garner said:

.....