Читать книгу W.E.B. Du Bois - Elvira Basevich - Страница 11

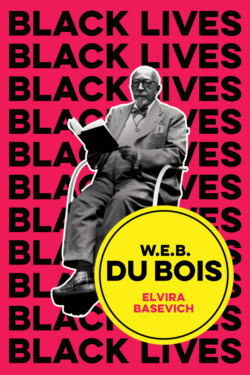

1 Du Bois and the Black Lives Matter Movement: Thinking with Du Bois about Anti-Racist Struggle Today

ОглавлениеDuring the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, on August 28, 1963, the prominent civil rights leader, Roy Wilkins, announced that Du Bois had died the night before: “If you want to read something that applies to 1963, go back and get a volume of The Souls of Black Folk by Du Bois published in 1903.”1 There are as many reasons why it is helpful to look to Du Bois today as there were in 1963 and in the early twentieth century. A voice from the past meditating on slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, Du Bois wrote about a world that appears bygone and foreign – a world that is not our own. One might wonder what his political critique can add to our understanding of the world today. His writings often conjure up images of dusty country roads, shaded by poplars, carrion-eating birds, and a fragment of dusk that approaches like a threat of violence. The takeaway from Du Bois’s writings is that today – as in the past – any meaningful political analysis must underscore our racial realities. In the United States, racial matters constitute the central obstacle to the flourishing of the republic and the central contradiction between empirical reality and democratic ideals. This is why Du Bois asserted that the problem of the twentieth century was the problem of the color line.2 The problem of race and racism implicates the entire nation and stretches across historical time. To motivate sustained public scrutiny of the significance of race remains a hurdle and explains, at least in part, why Du Bois’s writings continue to spell both trouble and an opportunity to reflect on our world. In response to the Holocaust in Europe, Hannah Arendt warned that “once a specific crime has appeared for the first time, its reappearance is more likely than its initial emergence could ever have been.”3 In his foresight, Du Bois intimated that the problem of the color line will reemerge as the problem of our century.

For those new to Du Bois, one might wonder why he focused on race and racism. Perhaps to a white reader unaccustomed to viewing the world from the perspective of race – or viewing oneself as “raced” at all – the analytic lens of race might appear to be forced or overstated. After all, we embody multiple identities and it is not clear why race should center our sense of self and approach to democratic politics. Though he had much to say about class, gender, and nationality, Du Bois reaffirmed that the institutional and social practices that signify the withdrawal of respect and esteem from people of color generally and African Americans specifically mediate the overall structure of American society, wherein racial whiteness functions as a license to assert unconstrained power. He thus posited that the fate of roughly 12 percent of the population has and will continue to determine the fate of the republic. This strong connection between the part and the whole may be true for other social groups, but he aimed to show why it is true with respect to the African-American community.

Du Bois’s abiding relevance for anti-racist struggle today offers insight into how the color line works today and how grassroots organizing might counteract it. The color line functions both to cause racial realities and to obscure their existence in a white-controlled polity. For Du Bois, to value black life across the color line is the central task of the republic, and successful grassroots movements illuminate disrespectful and derogating practices. In spite of the gains of the civil rights movement and the election of the first black president, the disrespect and derogation of the African-American community continues to undermine the legitimacy of the republic and test the commitment to democratic ideals for both vulnerable and privileged racial groups. A little more than a century after Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk, the Black Lives Matter movement emerged to condemn the killing with impunity of African Americans by officers and vigilantes. Because structural inequalities bolster police violence, as the movement grew, it expanded its focus to show the intersection of police violence with mass incarceration, poverty, de facto segregation, the devaluation of labor, and the loss of housing and education opportunities in black and brown communities. The call to disrupt police and vigilante violence against African Americans is the heart of the Black Lives Matter movement; yet the call also serves to bring greater awareness of black vulnerability in social, economic, and political life.

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement was sparked by the acquittal of George Zimmerman in 2012. Zimmerman fatally shot a black 17-year-old high-school student Trayvon Martin in a gated community in central Florida. After a police dispatcher had instructed him to step down, Zimmerman pursued Martin, claiming, “This guy looks like he’s up to no good, or he’s on drugs or something.” He continued, “These ***holes always get away.”4 Martin was unarmed and wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt; he had stepped out to buy snacks and it cost him his life. Zimmerman would later capitalize on his notoriety by selling online the gun he used to shoot Martin for US$139,000 and his amateur paintings of the Confederate and the American flags for as much as US$100,000.5

After Zimmerman’s acquittal, the co-founders of the BLM movement, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, demanded accountability for anti-black violence. In bringing the rash of legal lynchings into the national spotlight, the movement challenged public perceptions about the value of black life. For Du Bois, to counteract the phenomenon of the color line, the American public must be compelled to witness the black experience of America and to recognize that it stands in stark contradiction to democratic ideals. Not only do democratic institutions continue to fail to protect the most vulnerable members of the polity. The American public casts doubt about whether black lives are really in harm’s way. Many resent the call to even pay attention to the possible racial dimension of policing practices; the color line thus obscures racial realities. As a consequence, the basic right to life – to have one’s fair shot at being-in-the-world – is denied to African Americans; and it is extremely difficult to build more nuanced claims to justice when one’s basic right to exist is insecure. Hence the radical power of the assertion that black lives matter.

In chapter 13 of Souls, Du Bois depicted the fictional tale of a young black man, John Jones, who has returned to his hometown of Altamaha, Georgia after receiving a college degree in the North. A white mob lynches Jones for defending his sister against a white rapist. Du Bois narrated Jones’s last thoughts:

Amid the trees in the dim morning twilight he watched their shadows dancing and heard their horses thundering towards him, until at last they came sweeping like a storm, and he saw in front [a] haggard white-haired man, whose eyes flashed red with fury. Oh, how he pitied him, – pitied him, – and wondered if he had the coiling twisted rope. Then, as the storm burst round him, he rose slowly to his feet and turned his closed eyes towards the Sea.

And the world whistled in his ears.6

Though fictional, Du Bois’s account of the last moments of Jones’s life represents a moral truth about what it means to be a victim of racist violence. Jones was “swept like a storm” by the mob and, even as they asserted their gross claim to his physical body, he “pitied” his executioners; Jones saw their souls distorted by fury and fear in a way that they could not see themselves. In pitying his executioners, Jones asserted his spiritual sovereignty over them – that a vital portion of his self will not bend to their will. Of course, spiritual sovereignty can seem wanting against the destruction of the physical body. Du Bois’s insight here, I submit, illuminates black insight into white souls disfigured by bigotry and asserts the right to black hope for liberation. “But not even this was able to crush all manhood and chastity and aspiration from black folk.”7 In his stark rendering of the white soul, for Du Bois, their “pitiful” deeds cannot be the final judgment about, and summation of, what it means to be a human being; instead, he cemented the victims of lynch mobs as the rightful judges of America, as those whose souls must live on in our collective consciousness. So too the Black Lives Matter movement upholds the value of the black lives lost and elevates their experience of violence as the true reflection of American racial realities. “We must exalt,” implored Du Bois, “the Lynched above the Lyncher, and the Worker above the Owner, and the Crucified above Imperial Rome.”8

After Reconstruction, lynching mobs exploded across the United States. Between 1882 and 1968, historians estimate 3,500 African Americans were killed. The destruction of the black body was a public festival, complete with the sale of photographs and souvenirs of the cut-up bits of the victims’ bodies. In Dusk of Dawn, Du Bois recounted that when he found Sam Hose’s knuckles on display in a shop window in Atlanta in 1899, a recent victim of a lynch mob, his faith in science as a tool for racial justice reform wavered.9 Fact-based arguments alone could not stop anti-black violence or the family picnics around the burnt and mutilated remains of black people. He began to search for a more expansive way to combat the celebration of and complicity in racial terror. This history of violence has left a psychological imprint on the collective consciousness of the republic and today motivates, if not the celebration, then indifference and resentment against a movement to end police brutality. White nationalist groups have turned into an increasingly well-organized social force that seeks to reclaim the republic as a de jure racial caste system, reaffirming it as a white ethno-state. Today, as in the past, the claim that black lives matter is, in Baldwin’s words, a spiritual “cross” that the republic bears: the recognition, or the lack thereof, of black lives continues to define its character and shapes the history of its future.10 According to Du Bois, whenever the republic comes to value black life just a little more, it ushers in the radical reconstruction of modern American society.