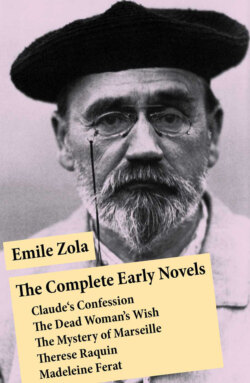

Читать книгу The Complete Early Novels - Emile Zola - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER XVI.

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

REMINISCENCES.

LET me regret, let me remember, let me review all my youth in a single glance.

We were then twelve years old. I met you one October evening upon the college green, beneath the plane trees, near the little fountain. You were weak and timid. I know not what united us; our weakness, perhaps. From that evening, we walked together, separating from each other for a few hours, but clasping hands with stronger friendship after each separation.

I know that we have neither the same flesh nor the same heart. You live and think differently from me, but you love as I do. There is the secret of our fraternity. You have my tenderness and my pity; you kneel in life, you seek some one upon whom to bestow your souls. We have a communion of tenderness and affection.

Do you remember the first years of our acquaintance? We read together idle tales, grand romances of adventure which held us for six months beneath their fascinating spell. We wrote verses and made chemical experiments; we indulged in painting and music. There was, at the house of one of us, on the fourth floor, a large chamber which served as our laboratory and atelier. There, in the solitude, we committed our childish crimes: we ate the raisins hanging from the ceiling, we risked our eyes over retorts brought to a white heat, we wrote rhymed comedies in three acts which I yet read to-day when I wish to smile. I still see that large chamber, with its broad window, flooded with white light and full of old newspapers, engravings trodden under foot, chairs with their straw bottoms gone, and broken wood horses. It seems to me pleasant and smiling, when I look at my chamber of to-day and perceive, standing in the middle of it, Laurence who terrifies and attracts me.

Later, the open air intoxicated us. We enjoyed the healthful dissipation of the fields and long walks. It was madness, fury. We broke the retorts, forgot the raisins and closed the door of the laboratory. In the morning, we set out before day. I came beneath your windows to summon you in the midst of darkness, and we hastened to quit the town, our game bags on our backs, our guns upon our shoulders. I know not what kind of game we chased; we went along, idling in the dew, running amid the tall grass which bent down beneath our feet with sharp and quick sounds; we wallowed in the country like young colts escaped from the stable. Our game bags were empty on our return, but our minds were full and our hearts also.

What a delicious district is Provence, biting and mild for those who are penetrated by its ardor and tenderness! I remember those white, damp and almost cool dawns, which filled my being and the sky above with the peace of supreme innocence; I remember the overwhelming sun and noon, the hot, heavy and fragrant atmosphere which weighed down upon the earth, those broad rays which poured from the heights like gold in fusion — virile and powerful hour, giving to the blood a precocious maturity and to the earth a marvelous fertility. We walked like brave children amid those dawns and scorching noons, young and frisky in the morning, but grave and more thoughtful in the evening; we talked in brotherly fashion, sharing our bread together and experiencing the same emotions.

The lands were yellow or red, desert and desolate, sown with slender trees; here and there were groves of foliage, of a dark green, staining the broad gray stretch of the plain; then, in the distance, all around the horizon, were low hills ranged in an immense circle, full of jagged spots, of a light blue or a pale violet, standing out with a delicate sharpness against the dark, deep blue of the sky. I can still see those penetrating landscapes of my youth. I well know that I belong to them, that what little of love and truth is in me comes to me from their tranquil delights.

At other times, towards evening, when the sun was sinking, we took the broad white highway which leads to the river. Poor river, meager as a brook, here narrow, troubled and deep, there broad and flowing in a sheet of silver over a bed of stones. We chose one of the hollows, on the edge of a lofty bank which the waters had eaten away, and in it we bathed beneath the overhanging branches of the trees. The last rays of the sun glided between the leaves, sowing the somber shade with luminous specks, and rested upon the bosom of the river in broad plates of gold.

We perceived only water and verdure, little corners of the sky, the summit of a distant mountain, the vineyards in a neighboring field. And we lived thus in the silence and the coolness. Seated upon the bank, in the short grass, with legs hanging and bare feet splashing in the water, we enjoyed our youth and our friendship.

What delicious dreams we indulged in upon those shores, the gravel of which was being gradually borne away every day by the waves! Our dreams vanish thus, borne away by the resistless current of life!

To-day these remembrances are harsh and implacable towards me. At certain hours, in my idleness, a remembrance of that age will suddenly come to me, sharp and dolorous, with the violence of a blow from a club. I feel a burning sensation running across my breast. It is my youth which is awakening in me, desolate and dying. I take my head in my hands, restraining my sobs; I plunge with a bitter delight into the history of those vanished days and take pleasure in enlarging the wound, the while repeating to myself that all this is no more and will never be again.

Then, the recollection vanishes; the lightning has passed over me; I am overwhelmed with grief, recalling nothing.

Later still, at the age when the man awakens in the child, our life changed. I prefer the first hours to those hours of passion and budding virility; the recollections of our hunting excursions, of our vagabond existence, are more agreeable to me than the far off vision of young girls, whose visages remain imprinted on my heart. I see them, pale and indistinct, in their coldness, their virgin indifference; they passed by, knowing me not, and, to-day, when I dream of them again, I say to myself that they cannot dream of me. I know not how it is, but this thought makes them strangers to me; there is no exchange of recollections, and I regard them in the light of thoughts alone, in the light of visions which I have cherished and which have vanished.

Let me also recall the society which surrounded us: those professors, excellent men, who would have been better had they possessed more youth and more love; those comrades of ours, the wicked and the good, who were without pity and without soul like all children. I must be a strange creature, fit only to love and weep, for I was softened and suffered from the time I first walked. My college years were years of weeping. I had in me the pride of loving natures. I was not loved, for I was not understood and I refused to make myself known. To-day, I no longer have any hatred; I see clearly that I was born to tear myself with my own hands. I have pardoned my former comrades who ruffled me, wounded me in my pride and in my tenderness; they were the first to teach me the rude lessons of the world, and I almost thank them for their harshness. Among them were sorry, foolish and envious lads, who must now be perfect imbeciles and wicked men. I have forgotten even their names.

Oh! let me, let me recollect. My past life, at this hour of anguish, comes to me with a singular sensation of pity and regret, of pain and joy. I feel myself deeply agitated, when I compare all that is with all that is no more. All that is no more are Provence, the broad, open country flooded with sunlight, you, my tears and my laughter of other days; all that is no more are my hopes and dreams, my innocence and pride. Alas I all that is are Paris with its mud, my garret with its poverty; all that is are Laurence, infamy, my tenderness and love for that miserable and degraded woman.

Listen: it was, I believe, in the month of June. We were together on the brink of the river, in the grass, our faces turned towards the sky. I was talking to you. I have this instant recollected my words, and the remembrance of them burns me like a red hot iron. I had confided to you that my heart had need of purity and innocence, that I loved the snow because it was white, that I preferred the water of the springs to wine because it was limpid. I pointed to the sky; I told you that it was blue and immense like the clear, deep ocean, and that I loved the ocean and the sky. Then, I spoke to you of woman; I said I would have preferred that she were born, like the wild flowers, in the open air, amid the dew, that she were a water plant, that an eternal current washed her heart and her flesh. I swore to you that I would love only a pure girl, a spotless innocent, whiter than the snow, more limpid than the water of the spring, deeper and more immense in purity than the sky and the ocean. For a long while, I held forth enthusiastically to you thus, quivering with a holy wish, anxious for the companionship of innocence and immaculate whiteness, unable to pause in my dream which was soaring towards the light.

At last, I possess a companion, a spotless innocent! She is beside me and I love her. Oh! if you could see her! She has a sombre and unfeeling visage like a clouded sky; the waters were low and she has bathed in the mud. My spotless innocent is soiled to such an extent that. formerly I would not have dared to touch her with my finger, for fear of dying therefrom. Yet I love her.

I am laughing; I feel a strange delight in jeering at myself. I dreamed of luxury, and I have no longer even a morsel of cloth with which to clothe myself; I dreamed of purity, and I love Laurence!

Amid my poverty, when my heart bled and I realized that I loved, my throat was choked, terror seized upon me. Then it was that my remembrances rose up. I have not been able to drive them away; they have remained with me, implacable, in a crowd, tumultuous, all entering simultaneously into my breast and burning it. I did not summon them; they came and I yielded to them. Every time I weep, my youth returns to console me, but its consolations redouble my tears, for I dream of that youth which is dead forever.