Читать книгу Autopsy of a Comedian - Emilie Collyer - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

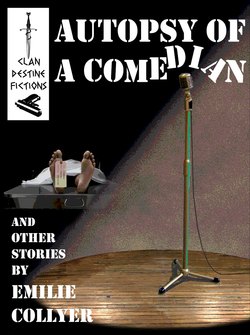

AUTOPSY OF A COMEDIAN

ОглавлениеI'm standing in darkness, in the hush before the storm. The pounding builds up: blood rushing, skin tingling, chest heaving. Then there's an explosion of applause. Where's the mike? There's my light. Yes. I'm real. I'm born again.

Felix let Kavisha prep the cadaver on the table. He wondered if he even needed to examine the body.

Male, 66 years old. Occupation: Comedian. If it wasn't his liver it would surely be his heart: excessive drinking, smoking, most likely a poor diet.

'Anything in the clothing?' Felix called out to Kavisha.

'No signs of bleeding or trauma. Wool suit. Tailor-made by the look of it. Silk tie, Valentino shirt. Neat fingernails, clipped. Clean-shaven. There's something in the hair - wax, or cream? His eyes were open but I've shut them.'

'All right. No marks or abrasions?'

Felix readied himself and approached the table, lowering his voice as he did so. No matter how many times he did this and how diminished his professional desire had become, it was still a privilege to bear witness to a human life.

'Nothing. He looks… perfect.'

'What's his name, our comedian?'

Kavisha checked the file.

'It just says Sammy.'

You know, this is gig number 7,311. I've been on stage over 47 years. I wanted to get to 10,000 gigs. Could have too, if I'd stayed at five a week. Got enough material. The problem is getting the gigs. Those buggers in the big city venues stopped booking me once the grey hair started to show. Country towns are always good. There's always something going on. But it's the driving, you see. It cuts down the number of gigs I can do in a week. I won't reach that magic tenner now. Bloody buggers.

'Well, Sammy, let's have a look at you.'

Felix scanned the body to corroborate Kavisha's initial examination.

'Lividity in both legs. How was he discovered?'

'Well, according to this, the bar manager was the only person in the venue. Sammy was on stage, the manager went out the back to get some stock. By the time he returned Sammy had stopped talking, he was just standing there. No response to auditory stimulation. And the barman was too scared to touch him. He called the ambulance.'

Felix didn't recognise the fellow. He idly wondered at the career trajectory of a comedian. Fame might not have been the main goal. Still, could the effort really have been worth it if you got to the end of life and died performing to an empty room?

Sammy's eyes were closed but there was something about his face - an upward inflection around the mouth, a wrinkle of hope in the forehead - that was as if a question had been asked and not yet answered. Felix placed his hand on Sammy's chest. Of course the heart was no longer beating. What a ridiculous gesture.

Jokes are dead, they started saying, back more than twenty years ago. Now you just got to notice things and ask questions. 'What's the story with cheese?' 'How about airline food?' I don't know. Didn't seem like comedy to me so much as shopping queue conversation, but that's what they said. So I learned to do it. Then, of course, the young buggers jumped on what the Python fellas were doing, thirty years earlier. Absurd humour was all the go. Non sequiturs, physical stuff… kept me on my toes. But I did it. 'How many surrealists does it take to change a light bulb? Fish.' You know the kind of thing.

Felix made the first incision, swift and deft: shoulder to breastbone. Then sternum to pubic bone. He pulled the skin back. He sawed through the rib cage and cut away the sternal plate. Felix made a cursory examination of the organs as they lay, before removing them as one. He would study them later, in detail.

As he worked he described what he saw, which, to his surprise, was not very much. It was as Kavisha had said: on the surface there were no discernible signs of disease or deterioration; Sammy was virtually a perfect specimen of a human body. Except that he was dead.

His lungs were plump and pink, his liver lean and healthy. There was no scarring, no clots. The contents of his stomach were bland and uninteresting. In short, there was no indication whatsoever of a cause of death. It was as if Sammy had simply stopped, like an unwound watch.

Next was the brain. By this stage Felix had usually hit his stride and was operating in a state of semi-automation. But today the scalp incision was difficult. He had a creeping sense of invasion. And the vibrating saw added to the sense of intrusion. Felix found himself checking Sammy's fingertips as he worked, sure that he would see them twitch in protest or pain.

'Are you all right? Do you need to take a break?'

Kavisha's steady tone returned Felix to himself.

'Clean that up, will you.'

Embarrassed, Felix noticed that his momentary lapse in concentration had disrupted his usually pristine and contained technique. There were spatters of blood and fluid on the floor. It was disgraceful. He cut the brain stem with more force than was absolutely necessary, to reassert his control.

'What are the instructions for burial?' he barked at Kavisha.

'There aren't any.'

'Family?'

'Doesn't seem to be. The police are looking into it.'

Felix placed the brain in formalin, took samples of the major organs and instructed Kavisha to replace what had been removed and sew Sammy up. Given that it was likely there was no family and therefore no burial to worry about, he would let the brain set for a few weeks and then examine it properly.

He left Sammy on the table and left the room with a wrenching pain of separation. Why had this cadaver got to him? They never bothered him.

He refused calls for the rest of the day and punished Kavisha with silence.

Late that night, unable to rest, Felix walked from room to room searching for a radio he might have accidentally left on. He could hear a scratching, incessant muttering. Maybe it was coming from the neighbour's place. Felix pulled on his running shoes and went outside to check. Their house was silent and still. The muttering continued.

He went for a run, pounding the pavement, willing his body to exhaustion and his mind to submission. The voice got louder, clearer. So he ran faster, trying to escape it, until his muscles cramped and his bones jarred and his lungs were squeezed empty.

Take my mother-in-law. Please!

And he says to me: 'Come on bud, I asked you already, your money or your life?' And I says to him: 'Hang on a minute, I'm thinking it over.'

Why was 6 afraid of 7? Because 7 8 9!

What did one casket say to the other casket: 'Hey, was that you coffin?'

A man walked into a bar. Ouch!

I want to die peacefully in my sleep like my grandfather, not screaming in terror like his passengers.

'Have you eaten?' Kavisha's voice brought him back to reality.

'Hm?'

Two weeks earlier, had Kavisha stood over him with concern in her eyes, she would have provoked him into a tongue-lashing or an insult. Today, sitting quietly, he barely registered she was there.

'I have soup. Or sandwiches. A sandwich? You must eat.'

He was managing to work during the day, relying on his memory. But he could not turn down the sound of that voice. On and on it went, an endless stream of gags and wisecracks, half formed jokes, meandering banter and punch lines with varying degrees of punch.

And he could not bring himself to cut into Sammy's brain.

'Are you sleeping? You must sleep.'

Kavisha was kneeling down now, one hand on his arm, the other on his knee. He realised how little he knew about her. He focused on her, willing a way out of his paralysis.

'Where did you grow up?' he asked.

'Here,' she said.

'And your parents?'

'India.'

'Where?'

'Ahmedabad. In Gujarat.'

'Both of them?'

'Yes.'

She was sitting on the floor now, as if he were a teacher and she were one of his pupils.

'Have you ever seen a snake charmer?'

She smiled, 'Um, no.'

'I saw a fellow once, in India. Jaipur.'

She nodded, a flicker of wariness in her eyes pending tales of the "exotic East".

'He was very impressive. But more so for me… my grandfather used to tell me a story of a woman he once saw, she was part of a traveling show. She charmed snakes, lay on nails, had slabs of concrete broken over her body. She was able to do it because she was in a trance. She started as a fakhir's assistant but ended up being quite a celebrity. Koringa, she was called. I was fascinated. I grilled my grandfather, demanding he tell me how she did it, what the secrets of her trickery were. He always swore, black and blue, that there were no tricks. This woman defied the boundaries of the human body. I wanted so desperately to meet her.'

The hum of the lights overtook his words and Felix ran his fingers over his own arms and hands, the skin pale and papery, blue veins gently pulsing and all of it held together somehow. He held up his hands and examined his fingers, long and elegant.

'Look at them! Pianist fingers, or a poet. Mark my words,' his grandfather used to say. And Felix had thought that too. Something magical would unfold, would take him into the world.

But until it did, he would study hard and do what his parents told him and use those long fingers for the intricate work of medical examination. There was a degree of certainty there and he came to rely on it. His fingers accustomed themselves to seeking out facts. He had become increasingly suspicious of anything that could not be seen and proven. He pushed Koringa and her exotic, powerful body down deep, under layers of hard work and scientific results. But something about Sammy the failed comedian had brought Koringa back to life. And with it came the memory of himself as a boy and all he'd hoped for, all that he'd given up.

'That sounds… interesting.'

Kavisha's polite response brought Felix out of his reverie.

This was intimacy, he supposed, letting someone share his frailty. Felix was generally not a man who welcomed intimacy.

'Shall we go over tomorrow's schedule?' Kavisha released them from the awkwardness. Perhaps she did not welcome intimacy either.

Her black trousers swished and her soft shoes padded across the floor. She brought back paperwork, held together in a folder. She read out some words. He nodded and said "Yes", and "Right" a few times so she would know he was listening. He hoped she would recognise the strange story about Koringa as an anomaly that would not interrupt their working life again.

'You won't stay much longer, will you, Felix?'

'No,' he replied obediently.

'Take care,' she squeezed her thumb and forefinger around his arm, just above his elbow. 'Get some rest. Just… let us see what the brain tells us and let that be all. He had a good life. You don't have to solve it.'

Kavisha was soothing and matter of fact. And then she was gone.

I'm going to die tonight on stage. I can feel it. The gut's never wrong. You get good gigs and bad gigs. Crowds that adore you and crowds that hate you from the minute you walk out, nothing you can do about it. But you can't not go on 'cause you know they're going to hate you. Just like you don't go on 'cause you think they're going to love you.

You just go on.

Whoever is there-that's your audience. You do it for them and they deserve your best. Even if they've wandered in 'cause it was the only place they could find for a beer, or they're having an affair and this is where they come so no-one will know them.

I didn't expect this though.

The barman's not a bad sort. Has the decency to look embarrassed that there's no-one here. I go on. What else can I do? Someone might come in.

Then when he goes out the back, it hits me. The room's empty. And I know then that I'm finished. I always said that. One person is an audience. But the first time there's absolutely no-one, well, that would be my last gig.

Felix had arranged for the body to be embalmed. This was done at his own expense. There was clearly no need. But the thought of letting Sammy's body decompose while he waited for the brain to set enough for proper study had seemed too cruel.

He fetched Sammy's clothes from where they were hanging in the dry cleaning bag. Then he slid open the drawer.

There it was: that look of hope on his face, or was it faint amusement?

Felix took his time to dress Sammy. It was not an easy task. The limbs were thick, unyielding and heavy. He should have asked the embalmer to do this. It was much more his line of work. Yet there was something vital in Felix's involvement. So he worked on patiently, finally buttoning Sammy's white cotton shirt and fixing his tie in a Windsor knot with some relief.

Knock, knock.

Felix looked around, certain that no-one else was in the cool silence of the examination room. He licked his lips, cleared his throat and spoke.

'Who's there?'

He sensed Sammy's body twitch, saw the faintest ripple across the face.

Boo.

Felix hesitated, but only for a moment.

'Boo hoo?'

His voice sounded small and he felt like a fool for indulging in this fantasy. Felix shook his head and turned away from the body, rubbing his face to return to sense, to reality.

Don't cry. It's only a joke!

A laugh escaped Felix, exploding from his mouth like a bark. He turned back to Sammy.

'I…'

This was crossing over into insanity. Not only was he listening to a dead man's jokes, he was responding. And now he'd initiated a conversation. Felix swallowed back the claggy nervousness.

'Well, I'll get it. Thought you might enjoy… that is …'

Take your time, take your time. I'm not going anywhere.

Felix nodded, gruffly, and strode into the office. He threw open the metal cupboard, the one he'd been meaning to clean out for years, and reached up to the top shelf. He pulled the dusty cassette player down, returned to the examination room and plugged it in. Then he inserted the cassette with fumbling fingers. If Felix ever observed a student with such shaking hands he knew it revealed a personality ill-fitted to the job and he did his best to dissuade, bully or terrorise them into giving up.

He pressed play, dragged a seat over and took his place next to Sammy. The two of them listened to the greats for hours on end. Felix had scoured libraries and second-hand shops and garage sales and music stores. They listened to The Goons and Spike Milligan, Bob Hope, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, Monty Python, Richard Prior and Robin Williams. They listened to the ridiculous, the foul, the angry. And as the night wore on Felix could not help but be moved by the compassion and frustration; the urgency in these men. These minds battled to find some kind of answer, to make whatever peace they could with the world. He laughed and wept and gave himself to the beauty and bewildered humanity of this elusive art.

Brilliant. Brilliant! Now let me finish off the night, in my own humble way. Not like the greats-that's for sure, you got that right! But I'm happy to be in their lauded company even for one night. Much obliged to you for this. Never thought I'd have such trouble winding up. Normally my timing's impeccable. But tonight, I just can't find the right gag. Always end on a gag-that's essential.

Have you heard this one? Two friends are out walking in the bush. One of them keels over. His friend runs to find the nearest phone and calls emergency services. The operator tells him to calm down. 'Now,' says the operator. 'First, let's make sure your friend is dead.' There is silence, then the sound of a gunshot. Then the man says to the operator, 'Okay, I'm sure he's dead. Now what?'

Felix fetched the brain and released it from the formalin. It rested on the bench, ready for dissection. As he cut through the firm resistance of tissue, adrenaline rushed through him to the rumble of cascading laughter. A shower of rapturous applause filled the room. Tears streamed down his face as he continued to cut, severing the brain into smaller and smaller pieces. Felix ensured that the job was done right so he could finally release Sammy from the world and let him rest in peace.

The sound of applause and cheering rose to a frenzied peak and Felix felt, as Sammy must have, the thrill of performance. How different his life could have been. Where would his life have taken him had he listened to his boyish eagerness and followed the path of Koringa, rather than the safe route his parents had set out?

'Thank you, Sammy,' Felix's voice was not small now. It was rich and full of gratitude. Sammy had lived a life driven by passion. Felix had been consumed by the fear of never being good enough and had forced himself to rely on certainty rather than experiencing the exhilarating joy and terror of stepping out into the unknown.

Finished with his task, his hands trembling, Felix lowered the scalpel. He was relieved to his core that he could step away, into his own unknown territory, for what remained of his life. His neat, hand-written resignation letter lay on his desk, ready to be sealed and handed in.

He turned back to Sammy, just in time to see the corpse rise. Resplendent, Sammy took his final bow.

Goodnight folks and thank you. A pleasure as always! God bless you all. And as two wise men once said: 'It's good night from me…'

The punch line hovered as the room fell silent, electric with anticipation.

'And it's good night from him,' said Felix as he stepped forward with arms outstretched, to embrace Sammy; to break his fall.