Читать книгу Kerry - Emily Herbert - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHO CARES?

ОглавлениеKerry Katona was thirteen years old. Quietly minding her own business, she was trying to ignore the shouting going on in the background. But this was more than the usual rows between her mother Sue and Sue’s violent boyfriend; this was getting quite out of control. First, the boyfriend slapped Sue viciously across the face. Then he turned on Kerry. As both women started screaming, Kerry was sure she was going to die.

‘Mum and her boyfriend were rowing and he slapped her,’ Kerry later recalled. ‘The next thing I knew, blood spurted out. Then he turned round to face me. I saw the flash of a blade and I was convinced he was going to kill me. We managed to fend him off until the neighbours came rushing in.’

Scenes of chaos and shouting ensued as the neighbours sought to hold him, while both women screamed for help. There had often been rows before, but this one had spiralled totally out of control and the neighbours knew that someone had to take action to protect the pretty schoolgirl and her mother and so, after some agonising, Social Services were alerted.

This was not the first time Social Services in Warrington, Cheshire, had been in touch with the Katonas. Sue had long been known to have mental problems and, although her own mother and sister helped as much as they could, there had long been concerns about her daughter Kerry’s welfare. The identity of Kerry’s father was and still is a mystery to her; her mother’s subsequent marriage seemed, for a while, to provide some sense of stability, but it had long since broken down. Since then, there had been a succession of boyfriends, none of whom were good father or husband material and none of whom were able to provide the security both mother and daughter so desperately craved. And now Sue had found herself with a partner who seemed set on doing herself and her daughter some harm.

And this was to prove the breaking point. Sue was told by Social Services to choose between her daughter and her boyfriend. She chose the latter. ‘I remember thinking, “Oh, Mum, couldn’t you for once have chosen me over him?”’ Kerry said. ‘But I had to forgive her. No matter what she did, she was all that I had.’

Indeed, the bond between the two has always been close and, in the light of Kerry’s marriage breakdown, has become stronger still. Neither should Sue be judged harshly; she had a mental illness that blighted much of Kerry’s childhood. But it was a harrowing time for both women and it would be some years before Kerry was old enough to make the break from her difficult background and strike out on her own.

Kerry Katona is a survivor. She’s had to be. If the secret of success is an unhappy childhood, then Kerry was destined for greatness from the moment of conception, because her childhood wasn’t so much unhappy as horrific. She never knew her father, and her mother’s mental illness left her unable to look after her child. Kerry spent years being moved from one foster home to the next, from one refuge to another, all the while desperately seeking a stability that, as a child, she never found.

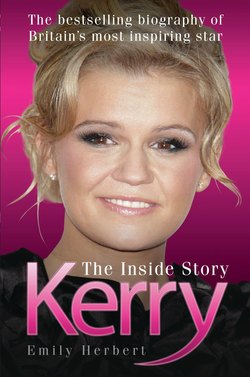

Now, of course, Kerry is one of Britain’s most famous celebrities, an ex-Atomic Kitten, an erstwhile Queen of the Jungle … and a star. But it has taken incredible strength to overcome her dreadful early years and become one of our best-loved faces. It could all have ended up very differently indeed.

‘I was so down,’ Kerry says. ‘I wanted to jump out of windows. I wanted to die. I really did and I just kept thinking I don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow. I didn’t have a very good childhood but Mum had the worst childhood of all and spent it mostly in care, too. She never really knew how to love, so I lived with my aunties, my stepdad, foster parents and in care homes.’ It was a very tough time, but it resulted in making Kerry tough, too. There is certainly a vulnerability about her, but it should be no surprise when she bounces back from adversity. She’s had to – right from the start.

Kerry Jayne Elizabeth Katona was born on 9 September 1980 in Warrington, Cheshire, and from the very beginning it was clear there would be trouble ahead. Her mother Sue had had an affair with a married man who had other children of his own, which resulted in her falling pregnant. The affair was over by the time the pregnancy was discovered; she was determined, however, to go ahead with it.

‘Susan was adamant she was going to have the baby,’ said Betty Katona, Kerry’s grandmother, who helped her granddaughter through some of her most difficult times, ‘although her relationship had already ended when she realised she was expecting. Kerry’s dad is probably kicking himself now when he sees how well his daughter has done. In a funny way, not having him around has helped Kerry – it made her want to do well and make something of her life.’

It was a brave decision on Sue’s part and so she went ahead and had her child. As she was growing up, however, Kerry felt the absence of a father as she began to realise she had only one parent. Indeed, she only discovered that her father was married to someone else when she was eight and, to this day, she has no idea as to his true identity. ‘I started looking at men on the street, wondering if one of them was my real dad,’ she admitted. She did not, however, try to find him. ‘Maybe it’s because I couldn’t face any more rejection,’ she said.

But like so many children who do not know the full story behind their past, Kerry has clearly been marked by the experience. For a start, the yearning to know more about her background remained. ‘I’ve never known my dad and he never got in touch,’ she said wistfully on another occasion. ‘But I must look like him because I’m not like my mum – she’s got dark-brown hair and blue eyes and I’m blonde with dark-brown eyes.’ It is a touching remark and a reminder of just how difficult her childhood was. Even today, Kerry retains a deep sense of insecurity even in her adult life as a successful performer. That said, she also has an extremely tough streak, one that has helped her to survive both her childhood and problems in her adult life.

Matters were not helped by the fact that the little family was desperately poor and frequently found themselves with nowhere they could really call home. There was never any money and the duo often had to rely on external agencies for help. ‘When I was a baby, we moved around women’s refuges,’ Kerry recalled. ‘I remember Christmas time in one of them when the Salvation Army came around with a big bag of toys.’

On another occasion, the family was so hard up they had to sell their pet parrot to buy essentials. Life was as harsh as it could be and, at that stage at least, the future seemed destined to be bleak. With disadvantages like these to overcome, it takes a will of iron to break free.

Eventually, Sue moved with her daughter to a tiny council flat, which was so small that they had to share a bed. But that did not herald the end of their problems; the years of dreadful insecurity had taken their toll and Sue’s health was worsening. When Kerry was three, she made a traumatic discovery – that her mother, who was by now twenty-three, had been slashing her wrists. It was an awful discovery for a child to make, especially one so young, but Kerry, as she always did, somehow managed to cope. Indeed, she was and remains completely forgiving of her mother for all the problems she endured as a child.

‘I always knew Mum loved me, but life wasn’t easy for her as she was a depressive,’ Kerry said in later years. ‘One minute we’d be laughing and joking, the next she would be telling me she wanted to die. I found out that she’d been slashing her wrists when she once rolled up her sleeves to wash the dishes. Wrapping bandages around her wrists became a part of my life. I knew if I wasn’t around, she’d be dead. That was a big responsibility for a little girl.’

As with so much in Kerry’s childhood, it had a profound affect on her later years and her relationship with her mother, which is now stronger than it has ever been. There were – almost inevitably, given the circumstances – periods of near estrangement when Kerry was growing up, but behind it all was always a very deep affection and an extremely strong bond, which might in part have been promoted by the fact that, even as a very young child, it was Kerry who had to play the maternal role.

The very fact that she grew up having to look after her mother when it really should have been the other way around created an added depth to the relationship. Kerry has never criticised her mother, never blamed her for anything at all in her childhood and always maintained that she wanted to be as close to her own children as she was to her mother. In those very early days, it was Sue and Kerry against the world and, even when they were living apart, that never really changed.

When Kerry was five, her mother married Arnold Ferrier, a kind man, and who already had four children of his own. There seemed, for a short while, to be some semblance of stability in the household. Kerry was devoted to her new father and was soon calling him ‘Dad’. It was the first time she had ever had a proper paternal figure in the background and someone with whom to share the burden of her mother’s illness. It marked a brief period in which Kerry was allowed to be a child, without the burdens of adulthood on her very young shoulders.

Like many little girls, she was also beginning to discover a love of dressing up and playing with clothes. Indeed, for the first time, the theatrical side of her character was beginning to come to light, as she started pretending to be taking part in a wedding. ‘As a child, I would run around the house pretending to be the bride and I would take my Mum’s white lace tablecloth and use it as the veil,’ she said. ‘It was my favourite game and I always imagined it was a really spectacular, grand occasion attended by really important people.’ Indeed, that grand ceremony was exactly what Kerry was going to get in years to come, when she fulfilled her childhood ambition and became the bride she had always dreamed about.

But that early happiness was not to last. Sue and Arnold split after three years, and Kerry initially stayed with her stepfather, partly because she was devoted to him and partly because of her mother’s mental health problems. Sue, however, swiftly decided that she wanted her daughter to live with her and launched a custody battle, which she won. Kerry was, after all, her daughter, and she was determined to look after her herself, difficult as it so clearly was. And it was a commendable decision, made for all the right reasons, despite the problems involved.

Sadly, however, life became even more difficult for mother and daughter, with Sue choosing a series of violent boyfriends, who would turn on both her and her daughter. ‘Some of Mum’s boyfriends used to beat the crap out of her and me,’ Kerry revealed. None of them compared to Arnold, who had been a loving and affectionate father figure to Kerry; indeed, they made life as miserable as possible for Sue and her child.

It was no life for a little girl and it was soon to get even worse. It had become obvious to everyone that Kerry simply could not continue living with her mother. Sue clearly loved her daughter, but equally was simply not capable of looking after her. And so Kerry was sent into foster care for the first time. By the age of 16, she would have lived with three different families before, with the fourth, at last finding some semblance of a caring and stable family life.

Kerry’s early fostering experiences were dreadful; she did not find the foster homes loving and later said she was treated differently from the natural children of the parents she lived with. There might have been awful problems involved with living with her mother, but at least she knew that Sue loved her and wanted nothing but the best for her daughter. That was not the case with the first three foster families Kerry was sent to live with.

She never settled down into any of the families, and never found any real sense of happiness, something recognised by her husband Brian McFadden before the two split up. ‘What she says to me is that her whole life people have let her down,’ he said. ‘She never met her dad. She had all these different foster parents and people always abandoned her or let her down.’ Sadly, of course, Brian was ultimately to do the same thing himself, although in the early years he was very aware of the trauma his wife had had to live through.

One benefit from all of this suffering was that it did establish in Kerry a very strong desire to make something of her life. ‘Being in Care made me even more determined to show what I was worth and that I could succeed,’ Kerry said later. ‘People can be judgemental about those who have been in Care, assuming they’re trouble, or stupid.’ It was, undeniably, a very difficult time in her life.

Neither was there much relief when she visited her mother at home, as Sue’s violent, self-harming episodes continued. ‘One day, Mum walked in with her wrists covered in blood. I couldn’t take it,’ said Kerry. ‘I told her if God wanted her dead, He’d have taken her by now. Then I flung her pills at her and said, “Mum, if you’re gonna do it, go ahead.” It sounds horrible but it was what she needed to hear.’

Indeed, it did the trick; that was the last time Sue tried to hurt herself. But it was a terrible stage for Kerry to live through. As a child, having to inflict ‘tough love’ on a parent takes a maturity far beyond most people’s years and, yet again, Kerry was forced to take on the parental role. Although still very young, Kerry was having to grow up fast.

The constant changes in where and with whom she lived caused problems in other ways, too. Kerry was constantly being taken out of one school and put into another – in total, she attended eight throughout her childhood – which meant that there was no continuity either in her education or in the people she met. Kerry was not naturally academic, but that side of her was never able to develop because she was forever changing from one school to another. It was hard for her to form friendships, too. Kerry has always had an outgoing, bubbly personality, but at that age children need to be in the same place for a while together in order to form firm friendships. Scarcely had Kerry had a chance to form one set of friends, than she was forced to start getting to know a new lot. All told, it’s remarkable that she has emerged as unscathed as she has.

Her grandmother Betty was only too well aware of how difficult the young Kerry’s life was back then. She did her best to help, but there was a limit to what even she could do. ‘It was very hard for Kerry as a youngster,’ she said many years later. ‘She must still go over it in her mind all the time. She was a happy-go-lucky kid, but it was hard for her. Some kids are tough and she was one of them. She used to stay with me now and again. But her Mum’s made up for not being able to be there for Kerry as a teenager and everything is OK between them now.’

Kerry did, in fact, also spend periods living with her mother before meeting the family that was finally going to help her, but it was the near-stabbing episode when she was thirteen that sent her back into Care, a life that she found utterly miserable. However, shortly afterwards, there was an all too rare piece of luck in a very difficult childhood.

Kerry met Fred and Margaret Woodall, an event which turned out to be a great success. Kerry went on to live with them for three years from the age of thirteen, a period that, at long last, established some stability in her life and gave her an insight into how most people lived. A tough little girl, Kerry would probably have turned out well whatever she did, but her association with the Woodalls undoubtedly gave her a boost.

‘They gave me a chance in life,’ she said, looking back upon her childhood. ‘They and their son Paul, who is five years older than me, showed me what real family life is like.’ They gave her treats, too, that many children take for granted, among them her very own bedroom and her first holiday abroad. Kerry, unsurprisingly, grew to love them as her own family, and blossomed in the time she lived in their house.

The Woodalls, who stayed in touch with their young charge after she moved out and are still very close to her – Fred gave her away at her wedding – have nothing but happy memories of the time Kerry remained in their care. They were also extremely sensitive to her particular situation – that she and her mother loved one another, but that it was simply not practical for them to live together at that stage – and gave her the space to continue her relationship with her mother, while at the same time building up her confidence and happiness. She also began to develop into a typical teenager, who sometimes had to be kept in check.

‘Kerry told us that she loved her Mum and would not swap her for the world,’ said Fred. ‘We never asked her what she had been through and she didn’t volunteer anything. But she loved her time with us and she was a joy to have. I occasionally had to tell her off for wearing skirts that were too short, but I suppose that happens in most homes. With everything she’s been through and all she’s achieved, Kerry’s an inspiration to anyone. She’s proof that anyone can make it if they want to enough.’ Of course, she was also helped by having the love and support of a new family behind her, one which was determined that she should have as normal a life as possible.

They also imposed limits, something that did the young Kerry a world of good. ‘Fred taught me what it is to have a strong, supportive father figure in your life,’ said Kerry. ‘He and Mag showed me what real family life is like, which I had never known before I met them. They taught me discipline, though I was never a naughty kid. Mag used to ground me sometimes because I was such a little entertainer. I’d always be performing for her.’

It is a great credit to the Woodalls, to Sue and to Kerry herself, that she managed to see the positive side to her experiences. In a childhood as problematic as Kerry’s, the individual concerned tends either to sink or swim, and Kerry most definitely swam. Although she has spoken as an adult of her very difficult upbringing, she has never blamed her mother – rightly, as her mother was ill – and refuses to indulge in self-pity.

‘I’m not one of these pessimistic people thinking “Poor me”,’ she said. ‘I got to meet a wonderful set of foster parents. With others, there were stupid things like parents giving their foster kids the cheap Rice Krispies while their own children got the proper ones. It was horrible because I didn’t know these people and kids at that age are cruel. It was lonely but you got on with it. You have to. The way I look at it, tomorrow’s another day.’ It’s an attitude that has stood her in good stead since then. The world of showbusiness is one of the toughest in which to make a mark and the fact that Kerry learnt early on how to be able to put the past behind her and move on to new areas was to help her enormously in the years to come.

It was while she was living with the Woodalls that Kerry first began to think that a career in showbusiness might actually be feasible. Until then, such a dream would have seemed impossible – a mother suffering from depression, a poverty-stricken background and life with a string of foster parents were a very long way from the glittering career that Kerry was ultimately to make her own. ‘I wanted to get into showbiz almost from the moment I could walk,’ she said. ‘I was always playing around in my nan’s house, performing songs and dancing around.’

But Kerry was beginning to see that it was a potential way out of the life she was then living and, more than that, it began to become apparent that she had some talent for it, too. School friends began to notice that she had a flair for music and was not averse to being noticed; it was as if she was beginning to flex a set of muscles she had not previously known she’d had.

‘She was always the centre of attention,’ said Michelle McManus, who was in Kerry’s class at Padgate High School in Warrington and who went on to be in a dance group with the soon-to-be chanteuse. ‘If she could get up and sing and dance in class, she would. She saw showbiz as her way of making something of herself. With the kind of life Kerry had, things could have turned out very differently. But she had a good head on her shoulders.’

She certainly did, and was sensible enough to be able to take the opportunities that were soon to present themselves to her. And the head of music at the school agreed, calling Kerry ‘a very strong performer in every way’.

As her sixteenth birthday approached, Kerry began to sense freedom. She was clearly not academic and was keen to leave school and set up on her own as soon as possible. The Woodalls had provided her with a real home and a great deal of love and understanding, but Kerry was turning into a young woman and wanted to live in her own space. But she was not, as yet, entirely clear what she was going to do. She had no formal dramatic training of any kind, and no one to advise her. It was a difficult situation, but one that began to throw up possibilities even then.

For a start, her figure had suddenly matured into that of a very curvy and desirable woman, something that could clearly be used to her advantage. But how? Kerry had no family in the world of showbusiness, no connections and no real idea about how to get into a world so far from her own. Similarly, neither her school nor the people she knew in Warrington had any idea how she should further her plans and, if truth be told, at that stage, most of them would have considered her wildly over-ambitious.

Indeed, if truth be told, Kerry would have agreed with them. She was only a few years away from stardom by this stage, unaware as she was, but even when that stardom finally came and embraced her, Kerry sometimes seemed to have trouble believing quite how far she had come, and just how successful she was. That is not surprising, given her background, but neither, given what she had been through, was the fact that she has always managed to remain down to earth. That is at least one element in the key to Kerry’s popularity – a lousy childhood combined with the fact that she kept her feet on the ground when she did become successful have made her admired in many quarters. Kerry has always managed, by and large, to bring out feelings of goodwill in others.

But back then, aged sixteen in Warrington, brimming with energy and not yet sure how to use it, Kerry had no idea what to do to make her mark and so she embarked on a path that was a high risk strategy, to put it mildly. She decided that it was in glamour modelling that she would make her mark.