Читать книгу Ms. Mentor's Impeccable Advice for Women in Academia - Emily Toth - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Ms. Mentor was born in late 1991, when Emily Toth stewed and bubbled with a thwarted desire to change the world of academics for women—or at least tell the younger generation Some Sordid Truths.

Having spent nearly a quarter-century in academia, and having survived all those years as an out-front feminist, often being a feminist when feminism wasn't cool…Professor Toth felt she had much to say to younger women. She wanted to share information about opportunities and ostracisms, truths and trickeries, pitfalls and platitudes (such as “this university values teaching ever so much” and “we're a meritocracy, of course” and “we treat everyone equally, even women”).

But Emily Toth found that many a new academic woman said, in effect, and with an admirable independent spirit: “Please, Mother, I'd rather do it myself”—find my own way, make my own mistakes. Having eschewed biological motherhood herself, Emily Toth found it ironic that her advice could be brushed aside by those who weren't even—wretched truth—her own daughters.

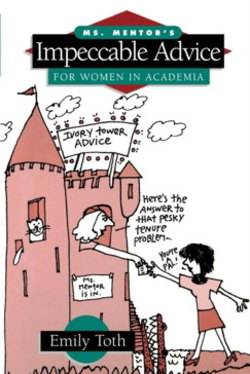

She is not, of course, disparaging the entire younger generation. Many a woman newer to academia used Emily Toth's counsel wisely; some were also grateful, publicly. One or two sent expensive posies. Yet Emily Toth longed to reach a wider audience—and so was hatched Ms. Mentor, a crotchety spirit who never leaves her ivory tower, from which she dispenses her perfect wisdom on all things academic. Like her counterpart Miss Manners, Ms. Mentor is impeccably knowledgeable and self-confident, and knows much more than anyone will ever ask.

Where E. Toth failed, Ms. Mentor would succeed.

And so “Ms. Mentor,” a column of advice to women professors, graduate students, recovering academics, and those who love them, made her first appearance in the spring of 1992 in Concerns, the journal of the Women's Caucus for the Modern Languages. Ms. Mentor dealt with, among other things, what to wear to academic conventions—a subject that got her denounced in certain circles for “triviality.” (But she still believes that the personal is political: poufy sleeves are not powerful.)

Soon letters started pouring in to Ms. Mentor, and not just from women in the modern languages. Readers were sharing her column and passing around dog-eared photocopies. A graduate student in forestry wrote; medical students chimed in; at least one affirmative action officer fulminated (Ms. Mentor adores fulminations). And so Ms. Mentor decided she would best reach her sage readers by writing an entire book of advice containing her ruminations and fulminations, gossip, anecdotes, and (of course—for this is academia) subjects for further study.

How many of your questions are “real?” is a question often addressed to Emily Toth when she goes abroad and it becomes known that she is in close direct communication with Ms. Mentor.

To which the answer is: All Ms. Mentor's queries are “real,” for all are about real-life problems. Many are letters sent directly to Ms. Mentor (c/o Emily Toth, English Department, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803). Others are questions posed to Emily Toth or to her vast network of friends, acquaintances, meddlers, scouts, critics, and needlers—all of whom are continually looking for new problems to solve, new diseases to cure, new worlds to conquer.

How many of your stories are “true?” is the other most-posed question—to which the answer is: All. Ms. Mentor leaves out a few identifying details, but the rest is all accurately reported. She reminds her sage readers that, given a system in which so many people have lifetime job security, many bizarre things can happen. Yet among the untenured, Ms. Mentor's major audience, there are indeed punishments for unconventional acts.

Ms. Mentor recalls, for instance, the crusty liberal arts dean who drove home unexpectedly one snowy afternoon and was greeted at the door by his very nervous, hand-wringing wife of twenty years. Brushing her aside, the dean strode to his clothes closet—which proved to be inhabited by a very untenured, very naked assistant professor of political science, who was making good use of his time by reading an old issue of the New York Times.

The assistant professor did not receive tenure, and out of this story Ms. Mentor has struggled for many years to derive a moral applicable to women in academia. She still has not succeeded—but finds it nevertheless an excellent tale, well worth retelling.

Ms. Mentor does, of course, attract other kinds of objections, the main one running something like this: “You are a mindless, bourgeois tool of capitalist patriarchy. Instead of encouraging community, you support individualistic solutions. You should be enabling your readers to work to overthrow…”

At which point Ms. Mentor tunes out, for she is not in the business of overthrowing capitalist patriarchy: her aims are far more modest, but much more immediate. She wants women to have power in academia NOW.

And so, rather than rock throwing (with which she does have some sympathies, however), Ms. Mentor prefers that women learn the fine arts of self-defense—and achieve the fine protection of tenure. A solitary woman, railing against injustice, has no power at all. But a team of women, all tenured, can speak with one voice and make the changes that will stop sexual harassment, achieve equal pay, get respect and money for Women's Studies, combat homophobia and anti-Semitism and class and race prejudices, allow paid leaves for child care and elder care, support accessibility and disability rights—and all the other things that are called “women's issues” and should really be human rights, and human responsibilities.

But only tenured professors have the power in academia—and so women need to get tenure. Ms. Mentor can help them, and will.

For only after tenure, can they really do what Ms. Mentor tells them to do.