Читать книгу Kids at Work - Emir Estrada - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

“If I Don’t Help Them, Who Will?”

The Working Life

At the age of fourteen, Joaquín identified an opportunity to earn extra money at his school to help his family. Joaquín’s mom was a sewing operator at a clothing factory in Pico Rivera and his father worked as a handyman. They provided for him and his two younger siblings, but as the oldest son, he wanted to help. Although he knew that school policy prohibited him from selling his wares at school, he did it anyway. With his extra backpack full of merchandise, Joaquín would spend recess with his customers, some of whom were also teachers. Joaquín remembered one day when a security guard at his school signaled for him to come over as he was dropping off books at his locker and picking up his “second” backpack. Joaquín’s friends looked at him with concern, but Joaquín walked over with confidence as he clutched his second backpack. At the end of the long hallway of metal lockers and blue-and-white checkered tile floor, the tall, muscular security guard waited for him with two dollars in hand. Joaquín took the money and, in exchange, gave him two small bags of chips and routinely asked whether he wanted Tapatio hot sauce.

Eighteen-year-old Joaquín laughed when he told me this suspenseful story in the living room of his house to explain his first experience vending food. His mother, Rosa, quietly shook her head and tried to control her laughter while she washed dishes in the kitchen. When Joaquín decided to sell chips, his parents were not street vendors, but one day he simply came up with the idea and told his mom, “Quisiera vender papas en la escuela” (I would like to sell chips at school)—and so he did. Joaquín opted to sell chips at school after seeing the demand for these types of snacks. He recalled, “A lot of people jumped the iron fence to go to the liquor stores” to buy chips because it was against school policy to sell chips and sodas inside the school premises. With enthusiasm Joaquín elaborated:

It got to the point where I had to take two backpacks full of chips because I was making money in high school. They already knew me. Every time I was at school, I was either doing my work or selling during my free time. They would come and they would ask me, “Do you have chips?” Teachers would ask me, too. The security guards used to buy my stuff. We had security in the halls to make sure we didn’t do graffiti. They would always see me with my bag and they would buy chips too.

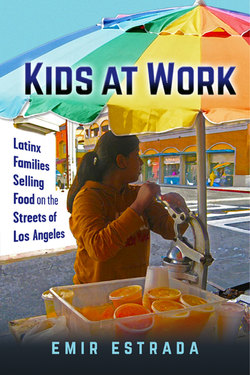

Figure 1.1. Boy making juice.

Little did Joaquín know that just one year later, circumstances would push him and his family to seek street vending as a financial alternative when his mother was fired from her job of fifteen years. Rosa had become ill over the years, and finally her employer decided to let her go, citing her undocumented status as a reason. She was fired with neither medical coverage nor severance pay. After Rosa lost her job, her husband became the only breadwinner. Again, Joaquín realized that his family was in need of help, and he chose to street vend with his uncles. Joaquín explained, “I went with my uncles one Saturday and I started vending. I helped them and noticed I made money. I said, I want to do this, and the first thing my uncle asked was if I was embarrassed.” Later, Rosa joined her son and together they sold fresh orange, carrot, and beet juice on Saturdays and Sundays at a busy business district in Los Angeles.

Joaquín continued going to high school while street vending and graduated on time. When I met him, he was a freshman at a state university in California, where he was double majoring in sociology and criminology. Sadly, Rosa did not see her son graduate from college. Two years after Rosa and her son started street vending, she was diagnosed with cancer and passed away while I was still conducting my study.

Figure 1.2. Girl making juice.

Joaquín’s story exemplifies the structural realities that motivate children to enact their agency in order to find economic solutions to help their parents. While it is well-documented why first-generation immigrants enter street vending, we know less about how and why children like Joaquín get involved in the family street vending business and what role they play in it.1

Street vending and family-pooled income strategies requiring that children work are common practices in countries like México.2 A good deal of research on child labor and street vending has been conducted in “developing countries” in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.3 However, these economic strategies are not uncommon in the United States.4 What explains this? Some commentators might assume that the children of immigrants engage in street vending in Los Angeles as a cultural holdover from México, their parents’ country. I argue that cultural explanations alone cannot explain why children and youth work as street vendors with their immigrant parents in East Los Angeles.

Structural Forces: “If I Don’t Help Them, Who Will?”

Joaquín’s story is also not unique among the children who shared their stories with me. All of the children in this study cited their parents’ lack of legal status and lack of access to formal sector work as the reason why they needed to help make ends meet. For example, Norma, who had just turned eighteen, and her younger brother Salvador, age twelve, faced an important decision to make when their father, Pedro, lost his job soon after they immigrated from México, where they had been living with their mother. Pedro left his wife and two children in México for ten years; in 2009 he used most of his savings to pay a smuggler to bring his family to Boyle Heights, California, where he used to share an apartment with other immigrants from his hometown.

Essentially, this family experienced profound ambivalence. On the one hand, they rejoiced at being together again after a long period of separation, and on the other hand, they faced the harsh economic reality of unemployment. Salvador was only two years old when his father immigrated to the United States; his father-son interactions mostly entailed weekly phone conversations and periodic gifts on his birthday. Norma has more vivid memories of her father before he left, but she too was having a difficult time adjusting to their new family arrangement in the United States.5 Before he brought his family to the United States, Pedro consistently sent remittances, and both Norma and her little brother Salvador focused entirely on their schoolwork.6 With his family now in Los Angeles, Norma’s father had to find a way to make money fast, but he was unable to find stable employment. When Norma’s father had the idea to sell tacos de barbacoa (goat meat), he first asked his children whether they would help. Norma explained,

My father asked us if we would agree to sell tacos de barbacoa on the street and he also asked if we could help him because they were not going to be able to do this on their own, and we said yes.

This is a typical conversation between parents and children when entering this occupation for the first time. This was unknown territory for all. Parents recognized that children’s help was important, and so was their opinion. After seeing the financial needs at home, moreover, the children made a conscientious and mature decision to help.

When I interviewed Norma and her family, they had been selling tacos de barbacoa in front of a junkyard for almost a year. The truck served as an improvised store tent, and a blue tarp stretched from the truck onto a hook Salvador helped screw on the wall. Salvador and his father were in charge of setting up their stand with two large folding tables, chairs for customers, and the skillet to heat up the meat and tortillas. Norma was almost always in charge of heating up the tortillas, while her mother and sometimes her father prepared the tacos and served a traditional birria broth in a separate cup (birria is a spicy stew made from goat meat). Salvador or one of the parents typically handled the cash transactions. During my time with this family, I saw Salvador inside the truck many times taking breaks and playing with his new portable video game, but after my interview with him, I discovered that he did most of his share of the work at home, the night before they street vend. Salvador told me that he is the one in charge of cooking the goat meat in the backyard of their house. When Salvador told me how he cooked the goat meat by himself, I could see a spark of pride, though he seldom looked up when he talked. At the young age of twelve, he had already become a master chef and was excellent at seasoning this traditional dish from their native town in Jalisco. Children like Salvador allowed me to see that there is more to street vending than the actual street work. Much of the work these kids do takes place off the streets because children are involved in many aspects of behind-the-scenes prep work. For example, while Salvador prepares and cooks the goat meat for several hours, Norma chops onions and cilantro inside their kitchen.

While children typically got involved in street vending work after their parents lost their jobs, soon they realized the importance of their work and family contribution. In many cases, refusing to help meant not being able to pay the rent, buy groceries, or even afford their own personal wants and desires such as toys, clothes, and technological gadgets.7 During my interview with fourteen-year-old Karen, she explained that she had convinced her mother to go back to street vending after she lost her iPod, a gadget that stored digital songs and pictures. In Karen’s case, there was no urgent need to street vend, but simply a desire to replace a very expensive toy that cost about $200. Her mother, Olga, recounted, “Entonces ella y yo volvimos a vender porque ella ahorita quiere un iPod” (So she and I started vending again because she now wants an iPod.) Karen understood that it is not just a matter of replacing an expensive gadget; rather, she must literally work to get a new one.8

Other children felt that they were the only help their parents had. Flor, who is getting ready to celebrate her quinceañera (fifteenth birthday), works with her mother on Saturdays. They sell cosmetics and snacks for pedestrians at a busy commercial area in Los Angeles. When I asked Flor why she helped her mother, she replied, “Si no les ayudo yo, quién?” (If I don’t help them, who will?) Children knew that street vending required extra help. Flor highlighted the importance of her work with a taken-for-granted example. She told me, “Sometimes I cover the stand while my mom goes to the bathroom.” This was important help, especially when vendors worked for long stretches at a time. As a researcher standing among street venders for hours at a time, even I was called on to help watch over a stand when someone had to run to the restroom at nearby restaurants.

Structural forces such as undocumented status and limited work for parents created opportunities for children to enter this occupation. However, children constantly highlighted their own agency in the process. Many rationalized their participation in street vending work with individual characteristics that, according to them, made them more apt for this type of work.

Which Children Choose to Street Vend in Los Angeles

Independent of structural forces, children in my study told me that their decision to street vend was their own. As a researcher, I was constantly aware of my position and wondered whether their responses were ex post facto rationalizations, and I remained unsure whether this was something they felt compelled to tell me. This is ultimately left for the reader to judge. The degree of their agency or free will was made more compelling when I learned that out of the thirty-eight children interviewed, twenty-four had siblings living at home who did not work with the family regularly or at all. Individual characteristics such as an outgoing personality or having people skills were often cited as good traits for street vendors. The children frequently defined themselves in opposition to their nonworking siblings who were too shy to do this type of work.

Fourteen-year-old Leticia, for example, had two brothers who stayed home while she worked with her mother. Leticia has a bubbly personality and seemed to be happy all the time. Her smile and laughter were very contagious. Their customers and I had a difficult time keeping a straight face when in the company of Leticia and her mom. While they constantly made fun of politicians, regular customers, and themselves, I had to be careful and stay on the periphery; otherwise I would also be fair game for teasing. According to Leticia, both of her brothers lacked her outgoing personality and were simply too shy. She was right. A few times, I saw her brothers quickly stop by their stand only to drop off merchandise for the business, such as tortillas, cheese, or vegetables. Other times, they simply stopped by to pick up food to eat. Leticia did not mind that her brothers did not work with them. Yet she justified her brothers’ lack of help:

The thing with my brothers is that they are very shy. They are not very social like me. I’m loud and talkative. They are calm and they say that I’m crazy. I guess I get it from my mom. She is always talking and always meets new people and I’m like that too. My brothers are shy. They don’t like to meet new people. I guess they are scared. When they come [to the street vending stand] they talk to people, but they just stand looking around like, “What do I do next?” and I’m just, like, “Well, come here, carry this and carry that.”

Similarly, Kenya said her older sister Erica simply lacked people skills to street vend. Unlike her, she did not have the personality needed to sell and handle rude customers. Kenya did clarify that Erica will help her mom as a last resort and only if no one else can help her:

Erica has gone [street vending] before, too. Whenever, like, I can’t go or my older sister couldn’t go. But she is like, “I just don’t like it. I can’t stand it there.” She is like, “I can’t sell like you guys do.” She doesn’t have people skills or anything. She is very nice, but she won’t go.

Sometimes children like Erica had siblings who were willing to work and thus shielded them from street vending responsibilities, but not from household work. While Erica could sometimes get away with not street vending, she often stayed home and helped with the household chores. There was certainly a gender dynamic at play, since girls who opted not to street vend—unlike boys—could not opt out of household work (see chapter 5). It is important to underscore that the girls in these families are doing critical housework and social reproductive labor. Although most of the sociology of family and work, as well as feminist literature, assumes that this work is carried out by adult women, here it is daughters who are carrying a big load, often in addition to the street vending.9

When I interviewed the parents, they reiterated that only those children who wanted to help did so because it was an optional activity for children. José described his children’s willingness to help:

It’s work without being work. It’s helping the family, but in a different way because it’s optional.… Well, we always ask our kids if they want to come with me and if they say yes, I bring them. It’s like when we go to the park. If you say, do you want to go to the park, and they say let’s go, then we go. [Author’s translation]

José’s children were interviewed separately and both echoed his views about street vending. When I asked his fourteen-year-old daughter Chayo whether she had to street vend with her father, she thoughtfully replied, “No, I don’t have to come.” Both Chayo and her younger brother Juan did not feel obligated to help their father, but both knew that not helping also meant missing out on the family business earnings of twenty dollars each. Juan, who is about to turn ten, said, “I like helping my family and all because I want them to do me a birthday party.… That’s why I’m trying to earn money to do it myself.”

For some children, the decision to help was, as José stated earlier, like deciding to go to the park. Linda and Susana, two sisters who sold pupusas with their parents, agreed to help in a very nonchalant manner as well. Linda explained, “One day my mother just told us if we wanted to come and sell. We were like, ‘Sure, we don’t have anything else good to do.’” According to Susana, she and her sister used to “take turns” going with their mother when they sold pupusas door-to-door before they sold at La Cumbrita, one of the street vending sites where I conducted observations. Negotiations over who would help street vend were often done among siblings themselves. While some rationalize being better fit for the job, others exchanged household work obligations with sisters who could stay home to clean, cook, and care for younger siblings. Those who were stuck or opted for street vending work were not shielded from the stigma associated with street vending and what seemed to be “the worst part of their job.”

Cultural Stereotypes: “They Tell Me That I’m Right Here … Like a Mexican Person Selling in the Streets”

Street vending marked the children in this study as foreign and undocumented even though the majority of them were born in the United States and had never traveled to México, the place they had been told to go back countless times. One thing was certain—street vending served as an immigrant shadow for these children. Sociologist Jody Agius Vallejo found that an immigrant shadow is even present among established middle-class Mexican professionals.10 Similarly, sociologist Tomás R. Jiménez argues that due to a constant immigrant replenishment from Latin America, second- and third-generation children of immigrants are seen as forever foreign.11 The youth in this study also experienced this “othering” while street vending. Their English language skills and even their own U.S. citizenship did not shield them from being labeled with an epithet such as “wetback,” to underline the racialized connotations of the job. Take the case of eighteen-year-old Veronica, who started selling cups of sliced fruit on the streets of Los Angeles with her mother when she was twelve. She recalled the teasing she had endured from school friends this way:

They used to tell me, “You sell in the streets? Aren’t you embarrassed? People look at you and you have to tell them to buy your stuff!” So they were making fun of me, and they tell me that I’m right here in the street, like a Mexican person selling in the streets. People tell me, “Ha! You’re a wetback!” … I wanted to cry because they were making fun of me, but then I got over it.

To be selling on the street is to be “like a Mexican person.” It marks one publicly as marginal, backward, subordinate, and inferior. Another girl also said that she imagined that people who saw her selling on the street probably saw her as “a Mexican,” when in fact, she identified as “Hispanic,” a U.S.-born U.S. citizen. She thought people would be surprised to learn she was born in the United States. This distinction and the street vendor youths’ contestation suggest the contours of widely circulating notions of racial hierarchy and immigrant inferiority.

The children were bewildered when random people told them to go “back to México.” These young vendors were proud of their Latinx heritage, and they did not accept derogatory cultural depictions of Mexicans and Latinx attached to them simply for the work they performed.12 Accordingly, the children I interviewed described their peers who did not work as “lazy” and “spoiled.” When asked what her friends do, Chayo, who had just turned fourteen but spoke with the security of a much older person, assessed, “Nothing. They have their parents, but their parents work for them. Like, they get money either way. They don’t have to do anything.” Her ten-year-old brother Andrés disparagingly claimed that his friends were always “outside eating chips and they are all fat.… They just, like, always play around and eat junk food all the time.” And Edgar disdainfully said of his Catholic school peers, “They don’t even work. They are lazy.” Not working was associated with slothfulness, junk food, and being fat.

Familiar and widely circulating racializations of Mexicans as lazy, illegal, and illegitimate were challenged by narratives that allowed the street vendor kids to position themselves as more authentically Mexican or Latinx than their nonworking peers. The street vendor kids said that their nonworking peers had lots of idle time. They reasoned that with all this idle time, their peers were more likely to get in trouble and turn to drugs, stealing, and gangs. Take the examples of the following three girls:

Street vending gets you tired, but you have, like, time to do it. And you’re not doing dumb stuff over there, seeing TV, sitting down, doing drugs, tú sabes [you know], not doing bad.… Like my cousin, he got into jail like three times already because he’s, like, stealing and doing drugs and he’s a gangster. I don’t want to be like him. (Nadya, age thirteen)

My neighbor just sleeps, smokes drugs, and then, like, he goes and eats and he doesn’t even help his parents. And I feel bad for his parents because one of them no puede caminar [cannot walk].… Like, if it was me, I have to help my parents. (Veronica, age eighteen)

Es mejor que estés trabajando que te cachen robando. [It’s better to work than be caught stealing.] I mean, that’s the way I see it. I ain’t stealing. (Martha, age eighteen)

Across the board, the children rejected traditional stereotypes of this profession. They countered the stigma by taking pride in this “cultural” activity that made them better Mexicans in the United States as it helped them develop a strong work ethic and kept them away from gangs and drugs. For street vending children, meanings of culture did not remain stagnant; rather, the children transformed and readapted cultural meanings through their work experience with their parents.

The children defined themselves as hardworking compared to their friends. For example, Leticia said that none of her friends could handle the work that she did with her mother. One night, Leticia’s friends had a sleepover and witnessed all the work that Leticia and her family had to do the night before they went street vending. This was not a typical slumber party that entailed nail painting and boy talk. Leticia took her friends to downtown Los Angeles, where they bought the majority of their food in bulk. Once home, she diligently put away the food and made sure to separate the food for their street vending business in one refrigerator, and in another fridge, the food for the house. Later, Leticia began boiling water in different pots for the different types of salsas that she made. In one pot, she boiled tomatillo and dried chiles, in another she boiled red tomatoes with jalapeños, and so on. Leticia did not count the vegetables before putting them in the pot, as someone would while meticulously following a recipe. She cooked with confidence and skill, as if she were one of the kids depicted in the cooking show MasterChef Junior. In total, she made about eight different types of sauces to accompany the food they sold. Her friends were overwhelmed just by seeing all the work she had to do and confessed they could not handle even part of it. During our interview, Leticia shared that story with pride:

Most of my friends have stepdads and their moms are always home. They mostly help around the house. One time my friends slept over for a weekend and they said they can’t handle it and they don’t know how I do it.

The children told me that they stood out among their friends. While some school friends who knew of their street vending work naively made fun of them, others regarded their work with admiration and respect. For example, Joaquín told me that his friends at first made fun of him, but later he gained their respect once his schoolmates saw how the fruit of his labor materialized.

At the beginning a lot of them made fun of me, but they started seeing that I made money. They would ask me, “How come you have money?” I guess they thought I was doing something wrong, and I tell them I always liked to make money and I found ways to make money by making good things.

The list of things children disliked about street vending was long: waking up early, dealing with rude customers, running and hiding from the cops, getting tired, and so forth. However, as Joaquín put it in a very mature and matter-of-fact way, “I think I have lived my childhood and I think it’s time to face the real world.” While children enacted their own agency, they also recognized that they had very limited options. Not helping would not only hurt their parents, but it would ultimately hurt them directly as well.

Figure 1.3. Handwritten work schedule of Adriana (age thirteen).

When Do Children Work?

Vacation Work

The children filled out a time schedule showing me what a typical week in their life looked like. One student jokingly said on her last day of school, “My vacation time has ended.” By this she meant that she worked more during the summer than she did during the school year. Others echoed this sentiment. When I looked at Leticia’s schedule, I was amazed by the number of hours she worked with her mom. She worked over forty-five hours per week. Immediately she clarified, “It’s ’cause I’m on vacation. I have more time now.” These young street vendors were ubiquitous on the streets of Los Angeles during vacation periods. In fact, I met most of the children in this book during summer and winter breaks.

Their street vending schedule was fluid and ever changing, but one thing was for sure: summer was a very busy time. Most children in the Los Angeles Unified School District are out of school during the summer. Budget cuts have greatly affected summer classes available to students in the Los Angeles area.13 Lack of summer classes means that more children are now idle at home, often watching television or playing in the street with their friends. This is seldom the case with child street vendors, though. In fact, summer is the busiest time of the year for the children and youth who work with their parents as street vendors. The summer days, with temperatures reaching the high nineties, are the best season to sell raspados, cut-up fruit, aguas frescas (fruit-flavored water), elotes (corn on the cob), and tejuino. Since they do not have school responsibilities, they are able to street vend during the day and stay late at night without having to worry about assignments due the next day or getting up early to go to class.

Figure 1.4. Handwritten work schedule of Josefina (age seventeen).

Weekends Only

Other children worked only during the weekend, but their weekdays were packed with household and childcare work. Take the case of Josefina as an example. My interview with Josefina started at sunset on the front porch of their small apartment, at around 6:00 p.m. Since she is the oldest, she is often left in charge of her little siblings. This was the case when I met her for our interview. Shortly after I arrived at Josefina’s house, her mom and stepfather drove out to do the laundry and she was left in charge of her fourteen-year-old sister Elsa, her five-year-old brother José, and her four-year-old brother Juan. During our three-hour interview, I was able to see how much work and responsibilities Josefina had on her plate. She makes sure her siblings eat, do their homework, and take a shower before they go to sleep. She also does behavior management. For example, her little brothers José and Juan interrupted the interview with a constant opening and slamming of the heavy iron front door. After a while, this banging noise became part of the background soundtrack that included cars passing by, children playing, neighbors blasting loud music, dogs barking, and a TV playing in the living room. The kids wanted attention from their sister and from me. Josefina constantly scolded them to stop, but my presence inspired extra curiosity that kept them peeking out the door.

An hour into the interview, we decided to move to the kitchen table, where there was light, because I had started using my phone light to read my interview questions. We passed through the living room, which was converted into a second bedroom with a queen-size bed, an armoire, and a large plasma television. Josefina’s younger sister and brothers lay on the bed watching iCarly, a TV show on the Nickelodeon channel. A curtain divided the kitchen from the improvised bedroom. Once in the kitchen, I sat on a chair by a small round table topped with a variety of food, including pan dulce (Mexican sweet bread), fruit, a box of small bags of chips, homemade salsa, and chiles curtidos (pickled jalapeños).

As in most of the houses I visited, the street vending merchandise was visible and stored around various living spaces. Josefina pointed at the few boxes of sodas and Gatorade bottles stacked next to the table and underneath it to explain what they sold on the weekend. In addition, she explained that she and her mother also sell hot dogs at a neighborhood park where large crowds join for friendly soccer games in the afternoon.

As we continued with our interview, Josefina’s five-year-old brother approached her for help with his kindergarten homework. We stopped the interview several times to help him with his homework. This involved reading the instructions, correcting what he had already done, and looking for crayons to complete the assignment. After the interview, I went to the street where her parents were street vending until midnight. Josefina still had to give her brothers and herself a bath, put them to bed, and finish her own school assignments.

Josefina’s street vending responsibilities have changed over time. She used to work more during the summer, but lately it has been more beneficial for her to stay home and care for her little siblings. She explained,

Well, I used to go more often during the summer. But now I have to stay home, so sometimes my mom goes by herself, but I mean, I have to do my homework.… [Also] I don’t want my brothers bugging my mom. So I keep them here at the house.… I keep my sister and my brothers here and I make sure they take a shower. I also put them to sleep because they don’t like sleeping early, but I make sure they go to sleep, and sometimes I clean the house.

In addition, Josefina is on top of her academic work and tries to protect her study time as best as family and street vending responsibilities permit. As a senior in high school, Josefina is busy preparing a graduation portfolio that includes a personal statement, a résumé, sample essays from previous classes, and more. Josefina gets as much work done as she can while she is at school and in her after-school program, but when she gets home, it is time to help her mother with the household responsibilities while her mother goes to street vend. Josefina explained,

Mostly the days that I would go help my mom is just Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays. If we go on Fridays, which is rare, but I’ll go because I don’t have school on Saturday. But I’ll go help her Fridays in the afternoon. Then Saturdays I help her the whole morning until, let’s say, like five in the afternoon. And Sundays the same thing, like 5:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

The children I interviewed had various work arrangements with parents. In addition to the type of street vending business, age, gender, and family composition helped determine when kids worked and how they helped. Others such as Josefina also worked during the week, but did so at home. Josefina seldom helped her mother with the street vending business during the week because her mother’s business required no preparation at home. Her mother sold chips, Gatorade, juices, candy, and hot dogs at night. Since Josefina had younger siblings, it made more sense for her to stay home and watch over them. In contrast, Leticia, who did not have younger siblings, worked during the week on the street, preparing food, charging customers, arranging the merchandise, and running errands for her mother.

School Nights and Weekends

In addition to helping over the weekend, other children also helped during the week after school. The story of Mercedes and her two daughters, Adriana (age sixteen) and Norma (age fourteen) comes to mind. Mercedes is a single mother and to support her two daughters sells tamales early in the morning before her daughters go to school. She also sells chips, sodas, and an assortment of candy outside Norma’s school immediately after classes let out.

Mercedes’s workday starts very early. She sells tamales at four o’clock in the morning outside a factory in downtown Los Angeles while her two daughters are still sleeping. One early morning, I accompanied Mercedes as she prepared for and then went to work. I met her at her house at dawn; it was dark but the streetlights allowed me to see her loading into her small car a thermos with champurrado. She also loaded a jug of freshly squeezed orange juice, a small folding table, and an ice chest full of about sixty tamales. When I asked Mercedes whether her daughters helped, she explained that every night they gather around the kitchen table to embarrar la masa (spread the corn-based dough before adding the filling). Mercedes and her daughters form an assembly line where the youngest daughter takes the corn leaves drenched in a bucket of water and places them on the table, while Mercedes and her oldest daughter spread the masa, add the meat and mole (sauce), and fold the tamales inside a large pot. Time flies by quickly since they have a small television in their kitchen where they watch their favorite novela (soap opera).

I decided to follow Mercedes in my own car since her small car could not fit all of her merchandise plus an extra passenger. Mercedes parked on the street immediately in front of the small side entrance of the sewing factory, and then she instructed me to park behind her. She strategically used her car and my car as a shield to hide from the authorities. She placed her small folding table as close to the car as she could in order to not block the sidewalk. On the light post she placed a small 13" x 10" cardboard sign with the word “tamales” advertising her food. Mercedes diligently sold to new and regular customers. She usually makes about sixty to a hundred tamales per day. On that morning, since she did not sell all of the tamales she and her daughters had prepared the night before, she moved to a different spot at 6:30 a.m. after the factory closed the door. I helped her move down the street directly in front of a bus stop. Mercedes planned to get customers who were exiting the bus. She finally finished selling all of the tamales by 7:00 a.m., just in time to move her car because street parking is enforced at that time. After we loaded the car with the empty wares, an empty crate, and the table, Mercedes headed home at 7:15 to then drive her two daughters to their different schools. By this time, both of her daughters were up and ready for school. As soon as Mercedes parked in front of their apartment, the girls ran out, helped take the table and the empty containers out of the car, and went to school.

Meanwhile, I began my interview with her sister and next-door neighbor Carolina. When Mercedes returned around 9:00 a.m., she looked exhausted, so she took a nap. Mercedes slept during my two-hour interview with Carolina. After my interview, Mercedes got up and started getting ready to go street vend outside her daughter’s middle school, where her youngest daughter will help. I met Mercedes and Carolina at the middle school at 2:00 p.m. after I also took a nap inside my car parked in the parking lot of a fast-food restaurant near their house. When I arrived, they were setting up their merchandise. I offered to help arrange the candy since she was busy with the first wave of hungry kids leaving the school. Mercedes thanked me for offering, but said that her daughter would help her. “I always try to leave some work for my daughter,” she explained. When her daughter came out of school, she placed her backpack behind the stand and started hanging candy on a string with clothespins.

Mercedes’s actions were significant to me because her decision to include her daughter in her sales represented more than needing her help. Mercedes left work for her daughter on purpose to teach her how to earn money. Instilling a work ethic in her daughters was one of the main reasons for getting them involved in the family business.

The Work Kids Do

This chapter illuminates the experiences of street vending children and their parents who experience multiple disadvantages. Children such as Joaquín, Norma, and Salvador reveal how their decisions to street vend were constrained by their parents’ limited employment opportunities. Over and over, children cited their parents’ job misfortunes as the catalyst to street vending. While lack of formal education, poor English language skills, and lack of legal residency status placed their parents at a structural disadvantage, the children in this study and their families found in these structural constraints an opportunity for self-employment through a collective family work effort.

The children highlight their agency and decision making when it comes to deciding to street vend and help their family make ends meet. Children are not thrilled that they have to work. Who can blame them? After all, street vending is hard work. However, most children showed a high level of maturity when explaining how they decided to help their parents. Through my conversations with these young entrepreneurs, they revealed that their motives extended beyond familial obligations. Their decision to street vend was also a solution to obtain expensive consumer items their parents alone could not afford. For example, wanting to replace a lost iPod, as in the case of Karen, is not a matter of simply asking for a new one; rather, children realize that they must literally work to get a new one. In the process of their work, children learned to see their work as unique and different from other children at their schools and in their neighborhoods. Instead of seeing their work as cultural baggage, they created a higher morality that sees them as strong, hardworking, good sons and daughters, and not lazy, delinquent, and a burden for their parents.

Street vending as a family enterprise is more than a cultural legacy from México (and more generally Latin America) that is induced by structural labor market constraints encountered by Latinx immigrants who face racial discrimination and are denied legal authorization to work in the United States. Street vending is an innovative form of self-employment, one that has created a market out of growing concentrations of co-ethnics, and now foodie tourists. We cannot explain the work of children in family business street vending as “either/or,” that is, as due exclusively to cultural factors or exclusively to structural factors. The line between culture and structure is not always so neat and definitive. For example, family household economies and the resources of poverty are structurally induced. In the United States, and in immigrant barrios such as East Los Angeles, hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrant families—many of them without access to legal authorization to work—have migrated and settled. Faced with saturated labor markets and poor job options, many of them have chosen to devise incomes of ingenuity, responding to the structural constraints they encounter in East Los Angeles with cultural resources and practices that are common in their country of origin. Street vending is a cultural and economic resource with which they were familiar, and which they employ to counter structural limitations they face in U.S. labor markets.

In the next chapter, we will see how structural and cultural factors are intertwined in history and place settings. The cultural factors that are important in explaining the popularization of street vending in East Los Angeles include the tradition of working-class communities buying and eating traditional prepared foods on the streets and around the plazas in México and other Latin American countries and the systematic exclusion of Latinx immigrants from jobs that offer a living wage.