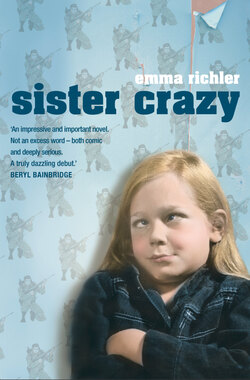

Читать книгу Sister Crazy - Emma Richler - Страница 8

Talking Man

ОглавлениеIn the elaborate Action Man games I played with my brother Jude, games sometimes lasting for days, interrupted only for school, mealtimes, and homework, and involving complex missions, actual trenches, and tiny fireworks, there would be the occasional real casualty. A casualty might suffer a scary burn and get earth in its joints. At the end of a raid, he would be found in a heap with his foot some distance from his body, yes, dead with his boots on. This was always Talking Man. He was the brilliant Nazi officer, foiled again, the blithe stormtrooper just following orders or the double agent committing his final betrayal.

I was nine years old, and I had a sneaking admiration for the German uniform. I liked the tunic nipped in at the waist, the slim lapels, the rakish jodhpurs, the high boots, and the helmet which was a tidy compromise between the austerity of the Russian one and the sheer blowsiness of the American. And yet, we shuddered to dress our top men in this uniform; we only had it for the sake of verisimilitude. It gave us an over the shoulder feeling – is anybody watching? – to put a man in it. We only did so when we had pretty hard knocks in mind for the wearer. Talking Man wore it a lot.

In the days before soft boots with delicate laces that you could actually thread through eyelets, Talking Man had a pair of hard tight boots and changing them one day, I pulled his foot off too. With one of my favourite guys, this would have induced tears in me, and a desperate oh no feeling, but when it happened to Talking Man, I felt a shady satisfaction.

What did I have against him? Of all my men, I remember him most clearly, perhaps for the wilful neglect I inflicted on his person as well as for a certain poignancy he represents for me to this day and which I am only now beginning to grasp.

I had acquired him through the Action Man reward system. With each purchase of an item from the Action Man directory, you were awarded stars in proportion to its value. For instance, a complete uniform – British Army Officer, German Stormtrooper, Alpine Commando, etc. – earned you maybe five stars. Whereas something from the Quartermaster’s stores – a flare gun and radio unit; a detonator, coil of wire, and dynamite; a mess kit; a map case and binoculars – only afforded you one or two. When you had collected twenty-one stars you won a free Action Man. A free Action Man! I chose Talking Man, who was an innovation at the time. My heart sank when I saw him. On the box, things looked good. There was an actual-size painting of a soldier on it, dressed in an RAF officer’s uniform, his mouth ajar in mid-speech; he was clearly caught up in some grave moment and the words would be jaunty and ironic. I could tell he was a man used to self-sacrifice – ferociously brave, romantic at home, amusing and generous in the mess. In my memory, he resembled Sean Connery. It was not seemly to open the box in the shop, and I was too excited, having actually exchanged twenty-one cardboard stars for a whole man, to expect deception. But they really ought to have shown Talking Man naked on the packaging. A small picture of his torso would have been enough. I was simply not prepared for the facts. His chest was a mess of perforations, like grotesquely enlarged pores. I have ever since been disgusted by displays of regular perforations such as honeycombs or Band-Aids, the raised papillae of a burnt tongue, a pig’s snout, moon craters, the magnified hair follicles in a razor ad, subway grates, cheese graters, the graininess of a blown-up photograph, aeration holes in a new lawn, the skin of a plucked chicken, the little holes on the surface of perfectly cooked rice. A plastic ring dangled from the middle of his back, below the shoulder blades, and attached to the ring was a long flesh-coloured string that coiled within the hollow of his perforated chest, an intestinal rope, a terrible worm. Otherwise, Talking Man’s features were regular, identical to all other Action Men, ones without stigmata, ones with minds of their own and no ready-made speech. And Talking Man’s speech was simply insulting. How could his two or three uninspired phrases suit all occasions? I don’t actually remember the few sentences in his repertoire, but they were of this ilk: ‘ATTENTION! FIRE DOWN BELOW! COVER ME! ALL HANDS ON DECK! ENEMY AIRCRAFT!’ That sort of thing. And if any of these phrases came in handy, how would you know you’d hit on the right one? Even worse, this burst of speech was preceded by the noise of the cord uncoiling, followed by a shuffle and crackle of interference like announcements in a train station. Why couldn’t he sound just a bit like Richard Burton in The Desert Rats or Jack Hawkins in The Cruel Sea? Instead, Talking Man might have been on drugs, or merely a simpleton. He never paused for thought. He did not experience doubt or pain or emotional stumbles of any kind. He just blurted out commands like a madman, all out delirium was a shot away. Then the military hospital – Northfield perhaps, near Birmingham – where he is deemed LMF. Lacking Moral Fibre. There he hides under beds and calls out in sleep to dead men, friends and enemies.

I expressed my contempt for Talking Man in small ways, quite apart from having him careen headlong into ambushes and walk over landmines. When we went on our family summer holiday in Connemara, I left him behind. When Jude and I made undies and little vests out of old socks for our men, Talking Man had only bare skin next to his scratchy uniform. Action Man™ designed lovely long socks as part of their new sports line, and Jude and I saved them for our best men. Jude even made little garters out of black elastic. Not for Talking Man, however, the comfort of a warm knee sock. His feet were always bare, in hard boots. Or rather, his foot was always bare, in a hard boot.

I found the new sports line irksome. A booklet was available in the toy shops, and in it were coloured illustrations of Action Man dribbling the ball, mid scissors kick, tackling, making a save, and kitted out in the colours of the most famous English clubs of the day: Arsenal, Liverpool, West Ham, Spurs. I could not reconcile the figure of my fighting World War II man and this frivolous sporting type. If at least they had been big shorts, like those of the thirties and forties, then I could work with the idea: our men are taking time out, on an RAF base, say, dispelling tension between raids, playing football with real yearning and abandon, expressing their comradeship in war, and nostalgia for their curtailed youth. They are very deft at the game, in an unfussy, self-effacing way. They are unselfish, laying off passes for men recovering from disfigurement, or men whose wives had perished in air raids or who were unfaithful to them, unable to live in fear of the awful telegram.

‘What is it, Alice? Bad news?’

For my men, praise in the course of a match would be generously deflected by jovial cracks at their own expense. Talking Man, of course, never played in these matches, even before his crippling accident, when he was sidelined due to craziness. I had seen some old footage taken by psychiatrists in one of the military hospitals, the Royal Victoria or Craiglockhart, set up during the ’14–’18 scrap, a film showing the funny walks of shell-shocked men. Names were given to all the funny walks, dancing gait, slippery footing on ice gait, fighting the wind gait, climbing up a mountain gait. Talking Man had dancing gait. He was a bad case and beyond rescue.

On the rare occasions when Jude and I allowed a guest player, one not to be trusted with our finest men, he would get Talking Man. Like our brother Ben, who was keen to steer our games into bizarre realms.

‘You know that many Nazi officers belonged to occult societies?’

Stony looks from Jude and me.

‘Well let’s say they stumble on these caves where satanic rituals are taking place and …’

Usually we just let Ben handle the fireworks for the true to life trench warfare, until, that is, he managed to melt the neck of one of Jude’s leading men.

‘Well done,’ Jude said aggressively.

‘Yeah,’ I added, ‘well done.’

‘But it’s so realistic!’ said Ben, eyes flashing. ‘What if all the men had some kind of injury and …’

Although Ben was our big brother, and in general we flocked to him for entertainment, he was terrible at Action Man. So we fell on a plan. If he were passing, Jude and I would act so engrossed in our game we didn’t notice him; it would be a faux pas on his part to ask to join in. This rankled with me a little and I felt hot in the pit of my stomach and would have an urge to leap up and chase after him, offering up my best man, the one with dark hair and an excellent physique, by which I mean, since all Action Men have the same build, that his joints were neither unyielding nor loose. He could wield a machine gun one-handed; he could crouch in a stealthy manner for any length of time without slipping, no worries. I saved up and bought him the beautiful uniform of the Royal Horse Guards, a ceremonial kit intended for dress occasions such as bashing off on parade or receiving honours, etc. Because our men were mostly engaged in missions of serious strategic complexity requiring them to slither through undergrowth, duck into abandoned cellars, scale dizzying heights and examine maps in hellish conditions, the Guards uniform was largely unworn. Until the time, that is, when Jude found pursuits that did not involve me so much anymore.

When Jude went off with his boyfriends, it was harder and harder for him to argue for my presence without calling a lot of attention to himself. He had a laconic demeanour and a fiercely protective nature and he needed all parties to be at ease, so the best solution for him at the time was to leave me out.

Once, I was allowed to play with Jude and his friend Michael, who was lean and silent and glamorous with ruffled fair hair. But during this game we were all a little stifled. It was an experiment doomed to failure, a one-off occasion. At home the next day, after school, Jude mumbled a message to me.

‘Michael says he enjoyed your presence,’ he said, passing me on the stairs.

‘My what?’

‘YOUR PRESENCE!’ Jude repeated crossly.

‘Oh. Great.’ I didn’t know what Michael meant about presents (what presents?) but I was aroused by this communication from him and I felt shifty, too, as if I had betrayed Jude somehow. In my mind, I thought I saw Jude take one more step away from me. The curtain was dropping on this episode of our oneness and so I let him go. But I refused to see it as desertion. No. We are SOE (Special Operations Executive). As natural leaders, we had to be split up. In Occupied France, two separate targets, and for our own protection, two secret routes. Would we survive? Will we meet again?

‘See you at the Ritz in springtime. Make mine a champagne cocktail.’

More and more, then, I took the white breeches and the scarlet coat of the Royal Horse Guards off the little coat hangers that Jude and I had fashioned from copper wire and I dressed my man in it. I dressed him by degrees and with languorous gestures I can only think of now as intimations of sensuality.

My man liked to read whenever he was not engaged on the field of battle. Jude and I made books for our men by cutting up the spines of comics. You could get about eighteen books from the spine of one single Victor comic, for example. A good haul. Then you designed a cover and stuck it on. The Last Enemy, All Quiet on the Western Front. Maybe even Wuthering Heights. My man always had a book in his rucksack. He reminded me of my parents’ friend Rex, a famous cinematographer who dressed in jeans and white T-shirts and blue cashmere sweaters. He had very elegant features and a band of flowing white hair around his otherwise bald head. He had a reckless streak and a languid demeanour. He answered yes or no to most queries in a languid fashion. He was not expansive. Jude and I spotted a German Luger in his house. The real thing. We were in awe. We asked Rex about it in hopeful and timid voices. He was elusive, which was downright glamorous to us, he came to me and held my long fair hair in his gentle grasp and asked airily, to no one visible, ‘Does anyone have a pair of scissors?’

Playing alone, I liked to sit my man on the edge of his khaki bunk, a book splayed and held open by the hand with the pointing index finger and thumb. ‘Death,’ he reads in The Last Enemy, his favourite, ‘should be given the setting it deserves; it should never be a pettiness; and for the fighter pilot it never can be.’ My man would be half-dressed in this moment of repose, wearing only his tall black Horse Guards boots with the silver spurs and his close-fitting white breeches with the lovely braces. I angled his head so he seemed to glance thoughtfully somewhere in the middle distance, which is an expression I had caught in my mother when she was reading. I tried to read this way myself, but lost a lot of time being distracted by other things out there in the middle distance and then trying to find my place on the page again. Never mind. It was out of duress that I played alone, but I was suddenly able to observe my man’s physiognomy at leisure and to allow him those moments when he could assume off-guard qualities, quite literally. The sight of him with the delicate white braces criss-crossing his slim, muscular, hairless chest gave me a distinct pleasure. The contrast of extreme formality with the undress of reverie lent him an air of vulnerability. Vanity was a foreign thing to my man. If pressed, he might own up to gratitude for his good looks, but he never traded them for favours, oh no.

Something thrown up in the drift of Jude’s wake, in his flow toward other people, was a new game we tried out together once or twice, a game involving my sister’s Barbie, a game that held him for a little while longer.

Barbie could not go far with us without overstretching the boundaries of truth. She could be a sort of Mary Ure in The Guns of Navarone, a commando with useful feminine wiles and a gift for disguise and languages. Or a nurse maybe, caught up in a daring mission and proving invaluable, Sylvia Syms in Ice Cold in Alex. An obvious choice was Barbie as French Resistance fighter, headstrong and relentless, going boldly where no French woman has gone before. There was also the aristocratic English girl, a master code-breaker for MI6. Women with no spare time on their hands, no time for dates, which is what I suspected Jude craved above all. And so most often, Barbie was a glamorous double agent, passing secrets to her man as he breezed through Occupied Paris, always an occasion for champagne and smuggled Russian caviar. Silk stockings and Virginia tobacco, rare as golddust, were regular features.

Something happened. I became tongue-tied and short of breath. My dramatic abilities failed me. My temples hurt. Later in life, in cases of sudden awareness on dates (Oh, I thought I liked you), when the urge to escape the sexual showdown is sharp as a fire alarm and you want to flee in cartoon time – in the first frame, one arm in a sleeve and coattails flapping; in the next, home in bed, reading a Tintin book – I would remember this atmosphere of disquiet and asphyxiation that came upon me with Jude and my sister’s Barbie. All I could do was stall.

‘Just a minute here! How did your man enter Paris? Subterfuge? Fake passport? Is my man with him? Shouldn’t he be? What mission is this? Shouldn’t he be in a hurry?’

Even episodes with the French Resistance girl of the one-track mind (Vive la France!) degenerated into dates. Crawling through darkened forests, sabotaging power lines, setting booby traps and gathering secret munitions drops, Jude’s man still managed to suggest dinner and dancing. So I revolted. I started to get silly as the walls of illusion came tumbling down, exposing the scene for what it was – sex – and Jude either got slaphappy along with me or stalked off in a fury. End of game. The second thing I would do was dry up, a startled and exhausted actor. I dithered and looked spacey and we would have to pause for peanut butter sandwiches. The third ploy was to say quietly, in a fit of uncommon generosity, ‘We should invite Harriet to play, you know. We shouldn’t take her Barbie and not ask her to play.’ End of game. Harriet was only six and extremely hopeless at serious games; even Gus could do better, and he was a baby still, two years old and not ready for war. So finally, in the absence of Jude, it was my fate to learn to play with her.

Explaining any new discipline to Harriet, you had to tether her to reality by introducing minor rules and practicalities, although never too many at once or she was liable to break off in the middle of things and start dancing to an unidentifiable tune of her own. Looking for Harriet, calling her to supper, say, or for school, you were likely to find her skipping around in the garden, a fairy on a happy day out in the ether. Harriet’s fierce whim was for collecting stuffed animals of all sizes, chiefly lambs and bird life, especially chicks, as well as a few bears and rabbits.

I gave her the lowdown on World War II. She needed to know the rugged truth in order to play, although she would dwell on the least vital points.

‘Yes but …’ Then the dancing around began, inducing wide-eyed exasperation in me. If I gave up, she wailed.

‘I want to play! I want to!’

Oh God.

I rehearsed her, but it was no good; before too long, there would be Barbie with her deranged look, handing out minute teacups containing drops of water to my Action Men, surrounded by the beasts of the field.

This was not like playing with Jude. Harriet didn’t really need me at all. I even left her with Talking Man, making out that this was something of a sacrifice, as if he were my favourite man. I watched her for a short while as I edged my way out. She was squeezing Talking Man into some of Barbie’s more loose-fitting garments – Transvestite Man now – and submitting him to minor indignities such as talking to animals, dancing and singing in his flounces, and preparing refreshments for a lot of chicks and little lambs. Meanwhile Barbie preened quietly, looking on from the sidelines, happy in a sort of maniacal way, grateful for the company. My sister even pulled Talking Man’s ring, suffering a jolt of alarm at the blurt of officious speech that issued forth. Harriet was simply not used to gruff commands except in fun, in our dad’s voice, say, the monster one he used when chasing her, stomping around the house with his hair all mussed. She did not like Talking Man’s voice at all. I saw her give him a startled look, then a cold one, as she went about wiping the event from her memory. She was really good at that, breezing on by things she didn’t like.

Jude and I had discovered one use for Talking Man’s urgent monotone. It was easy to induce dementia in him by making incomplete jerks of varying lengths on his vocal cord so that he’d only speak fragments of his stock phrases, which you could interrupt at random until he sounded ready for the white jacket with the long sleeves tied up at the back. This game had limited amusement value and Jude and I indulged in it only when flagging and war-weary and vulnerable to hilarity. I yanked Talking Man’s ring pull in jerks. ‘ATT-’ … ‘-DOWN BE-’ … ‘-HANDS ON-’ etc. We started yelling at each other.

‘Make me a peanut butter sandwich now!’

‘Have you done your homework!’

‘No!’

‘What’s for supper!’

‘Ask Mummy!’

‘Ask her yourself!’

‘Dismissed!’

‘Okay!’

‘Shut up!’

Jude and I are only fifteen months apart, and in spite of ourselves, I guess, we have a twin mentality, which time and distance cannot take away. Those are the facts. Jude likes to say from time to time, ‘You were a mistake. You were not supposed to happen.’

Considering I am not my parents’ last born, I do not take this seriously. I came too soon, okay, I can deal with that. I let him have his fun, though. I let him think I am slightly alarmed, but I am not. I have doubts about many things but I am absolutely sure that I was born out of love, despite my affinity for wartime.

Jude and I were steeped in World War II, although we were born some fifteen years after it ended. Knowing about the war gave me a sense of distinction, as if I, too, had suffered and overcome, emerging with my own badge of courage. I knew it as a black-and-white time, a place of shadows and relentless drizzle and austerity, of necessary violence and amazing resilience, a world in bold focus. I was there and Jude was with me.

Now I am in the room full of clocks where the voice calls out, WAKE UP! MOVE ALONG! HONEY, IT’S TIME!

I look at Action Man in 1999 and connect only with the name; everything else is strange to me. The packaging screams its gaudy colours of fire and blood and tropical locations, having all to do with fantasy and nothing to do with the high stakes and redemption that we played for. Even the man looks different, rubbery and matte-finished, with a sunbed tint and the vain five-o’clock shadow of the gigolo, not of the man suffering sleep deprivation and high anxiety. The men are marketed now under different names, clamorous titles of hollow intensity: ‘THE BOWMAN!’ ‘ROLLER EXTREME!’ ‘AGENT 2000!’ ‘SKY DIVER!’ ‘CRIMEBUSTER!’ ‘OPERATION JUNGLE!’ ‘SURF RESCUE!’ They have special vehicles: GYRO COPTER, and POLAR MISSION TURBO 4x4 fires as you drive! Mission cards are included and a disclaimer is written on the boxes, in more demure print: ‘Action Man™ does not identify with any known living person.’

Picking up these packages in the toy department, pretending to be shopping for a son or nephew, I feel a little scornful and superior. But what do I know about war? I crave the old me. Now I miss things like decision and certainty, beginnings and endings. In grown-up life, there are few demarcations. It is a great battlefield with constantly shifting fronts, that’s how I see it. Where, for instance, do I end and Jude begin? When does childhood end? No one ever said anything.

We were all corralled by our parents into watching a Steinbeck dramatization one evening in extreme youth, probably The Grapes of Wrath, and we lay on the floor in front of the TV stunned, literally, by the Great Depression. Everyone in the drama wandered about wearing skimpy, threadbare clothing and droopy expressions, speaking in defeated monotones, going to sleep on hard floors after a meal of one bulbous parsnip. The mother woke up the children at five in the morning, nudging them into readiness for another cotton-picking day. ‘Honey,’ she said to each one of them, followed by a gloomy pause, ‘it’s time.’ This scene happened at least eight times in the drama. My sister and I were sniggering wrecks by bedtime, hardly able to negotiate the stairs for hilarity. Waking up for school from then on we would say to each other, ‘Honey.’ BIG PAUSE. ‘It’s time.’

1914–1918. 1939–1945. I marvelled at a world at war and I could not fathom anything but conflict, beginning and ending with shocking decisiveness. I could not imagine the home front. I could not picture any casual activity at all. Surely shops were empty and gardens overgrown and any person without a gun in foreign fields could only stand on a rooftop with a helmet and torch or sit fretting by a window in a darkened house, straggly-haired and wide-eyed with grief and worry but steeled by virtue. Films, therefore, that showed the truth – that is, some semblance of normality going on at home while battles raged – were downright distracting to me.

‘I don’t understand, Jude. Why are they in a restaurant? Jude, why is she laughing? Jude, when is this happening? What is going on?’

Jude did not always answer me, at least not right away. Sometimes he would answer me several hours from the time I asked a question, or even the next day. I was used to this. That time, for instance, Jude came back from one of his Robin Hood sorties to the sweetshop. Jude stole sweets with his friends and shared them out at home. I found this diligent generosity poignant. So Jude said to me suddenly, passing me a red fruit gum, my favourite, ‘He is on leave. He is home recovering from a wound. She is hysterical due to war. It is not really a happy laugh.’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘Okay, thanks.’

I always knew which conversation he was resurrecting. I just did.

We were leaving home, where we were born, and moving to my dad’s country, where he was born, and we were sailing there on the SS Pushkin. We packed. Action Man packed. Jude decided we had to be a bit ruthless and thin out the equipment and the wardrobe. We could not take everything with us, so we made packages to sell to Jude’s friends. I did not know any girls in my convent school who played with Action Man; it was not a suitable marketplace. Besides, a convent does not encourage the entrepreneur.

Jude and I took shirt cardboard from Dad’s drawer and sewed on items of uniform, ironing the clothing first of all. The tunic would be displayed just so, one arm flung out and the other laid across the chest at an angle. The trousers we attached by two stitches and set in profile, the waistband tucked under the skirting of the jacket. Jude had stronger fingers and he stitched the shoes below the trousers and attached the hat or helmet above the jacket collar, where the head would be. The accessories were arrayed to one side, under the outstretched arm: gun, belt, pouch, water bottle, etc. There might be extras of our own design such as a book, a hanger, real braces with snaps, undies, or a vest. This gave the package real distinction. Jude then wrote out prices – £1.10, £1.70, etc. – and some slogan in eye-catching lettering: ‘MAKE YOUR MAN THE SMARTEST IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD!’ for instance. He even supplied stars at the bottom of the cardboard display sheet which you could collect and redeem against further purchases.

‘But Jude,’ I said, ‘what will we give away? We are taking the rest of the stuff with us. And we won’t even be here.’ I had visions of irate schoolboys clutching stars and yelling our names accusingly, forcing their way through a crowded quayside where the SS Pushkin was docked. But Jude waved all objections aside simply by looking at me with his slow gaze and not answering. In a finishing touch, we covered each cardboard sheet with cellophane and Jude took the packages with him to school.

I had an idea we could sell Talking Man. He could be marketed as a sort of special business extra – Casualty Man. Because mostly you would not want to sacrifice your best men in a scene with a lot of extras, and it was realistic to have strewn bodies, it would be a bonus to have a Casualty Man just for the sake of verisimilitude. I said we could advertise Talking Man right away as the FREE GIFT with stars, which would solve that little deception in one stroke. People would know what they were aiming for and it might even quicken sales.

Jude said, ‘I’ll think about it.’ This meant no.

What should I do with Talking Man? He was too pathetic to take with us and to me he suggested unmarked graves and dead men in transport ships, only recognizable thanks to identity bracelets. I thought of dockside welcoming committees, wailing women and stoical fathers with bleeding hearts and stone-cold corpses under shrouds on stretchers. And so I left Talking Man behind, accidentally on purpose. Forgive me, Talking Man, Ugly Man, One Foot, Enemy, Traitor, LMF Man, Shell-Shock Man, Missing in Action Man, Transvestite Man, Misfit Man – over and out. Au revoir, old thing; cheerio, farewell, goodbyee.

Jude is a foreign correspondent now.

I had a dream recently that I was on assignment with him. Real Action Men now. We are running in a crouched position in the water, along the edge of a river. We have automatic rifles. I am thrilled and I feel safe. My brother is a war correspondent and he cannot be killed. He fires at snipers while we scamper along but misses intentionally, signalling to them merrily. I am charged with pride. I glance back at the snipers and see in their faces a calculated pretence of gratitude. They do not care that Jude spared them and suddenly I know they will shoot him. I need to warn him but it is too late. They shoot me. My face is falling into the water, I fall slowly. Oh-oh. My back feels hot.

‘Jude, am I hit? Jude, am I?’

Jude says, ‘No. No.’

‘Oh, I think so,’ I say, smiling a little. ‘Yes, I think so, Jude.’

I am aware of the coming oblivion, the terrible loneliness of death, and I see this reflected in Jude’s eyes as I fall into his arms. I know we are too far from help. His look is grave, wary; he is speechless with impending loss, although his actions are careful and practical, plugging the exit wounds with his fingers, supporting my drooping head, as if in not recognizing death rushing toward me, he can prevent even this.

Jude has a knack of choosing to investigate a place that is about to be torn apart by hostilities, a place rife with fanatics and con men. He has a tendency to stand up in press conferences and ask provocative questions in the most unassuming way, with gravity and charm. He is probing and brave and he rallies people to him. I hope his charm will protect him. I hope his charm is bulletproof.

I watch him walk away from me after sharing a drink on the eve of an assignment and I note the loping strides he takes, even though he is not a tall man. I note his head tilted to one side slightly, tilted in thought, and that he moves away at a pace never faster than ambling, although I know his bags are not packed and he leaves in less than three hours. To my surprise, I think of Talking Man. I imagine I hold the ring pull of his speech cord and the farther Jude walks from me, the longer and tauter the cord becomes. I must hold tight because if I let go, Jude will find himself, I envisage, rooted to the spot, and with the release of the tension he will feel real fear for once, and there will come from his mouth a vulnerable rush of speech, a babble of strange words, and he will be lost.

Wherever he is, and no matter what, even flying gunfire and so on, Jude calls me on the telephone when he is reporting from a war-torn place. Wherever he is. He might ask me a sporting question. How is my team doing? Who scored? He might send me on an errand. Please water my plants. Please call my office. Please prune the peony bush. He might describe the meal he just ate, his room, or some arresting vision he has seen in the strange place he is in. This time, though, I have not heard from him in twenty-three days. I wake up sometimes in the middle of the night. I am wide awake, my heart is hammering, my throat parched, my teeth aching from clamping my jaw shut in fitful sleep. I call out his name and I ask, ‘Where are you?’ I say it a second time, more quietly, ‘Where are you?’

I am in the room full of clocks and now there is no voice, just ticking. It’s okay. I’m holding tight, I won’t let go.